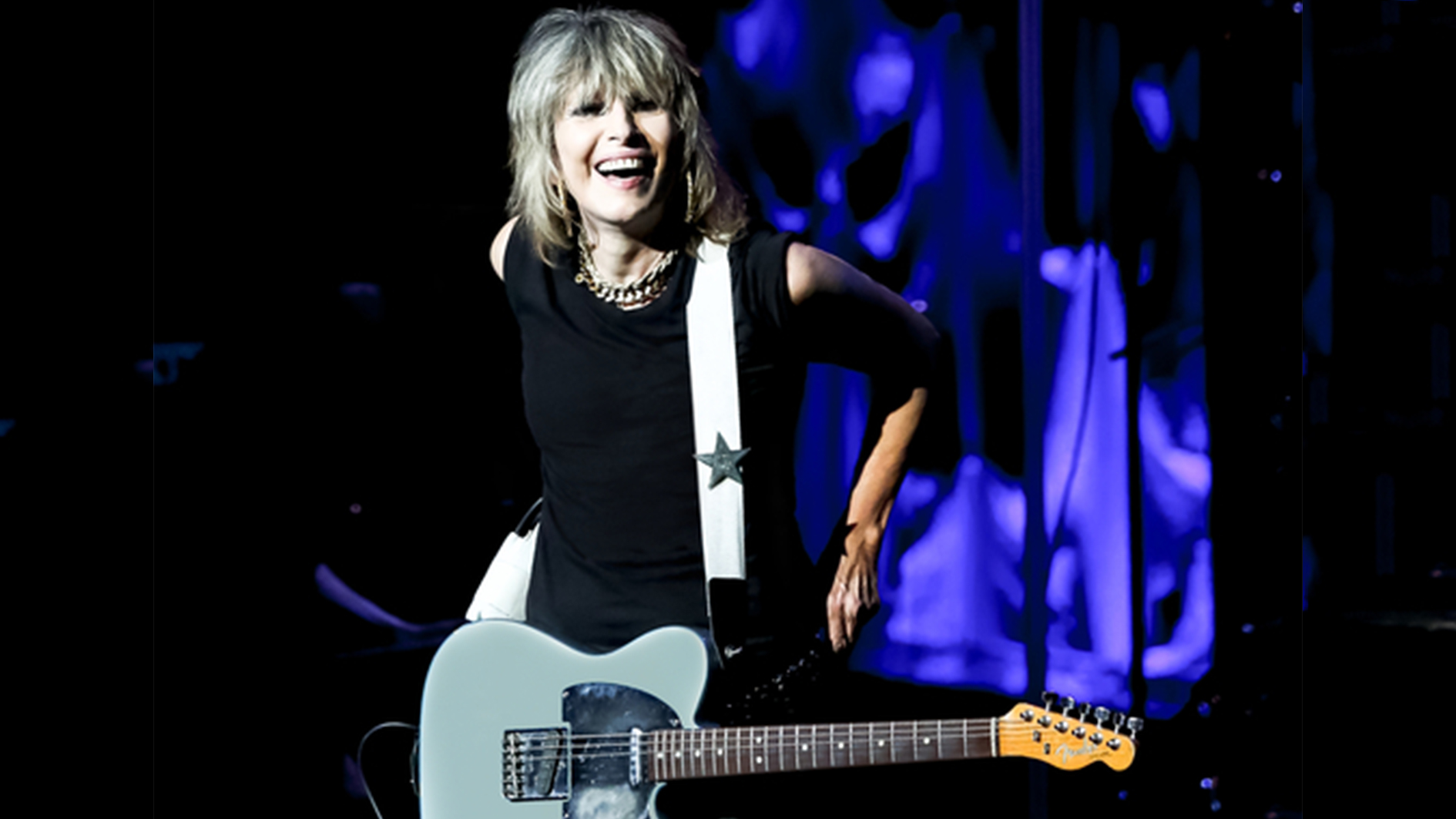

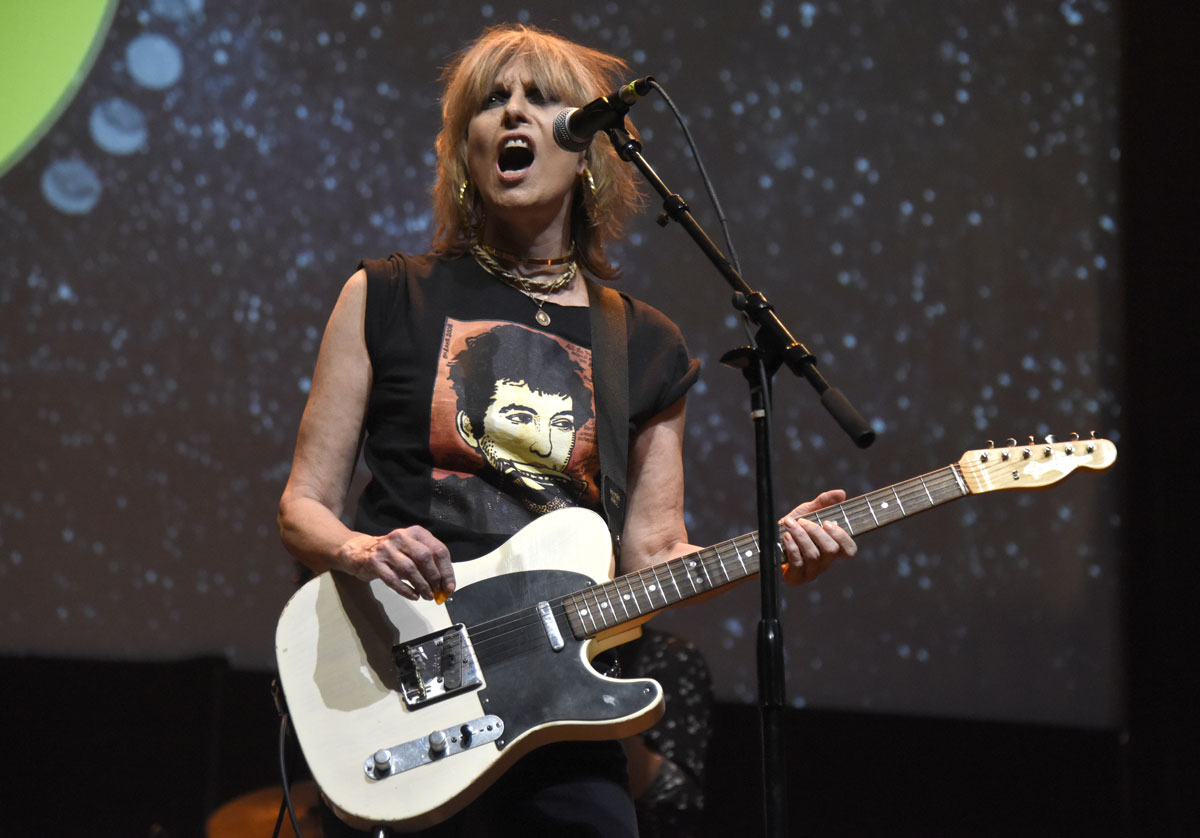

Chrissie Hynde: “I don’t think of myself as a songwriter or a guitar player. If I have to write on a form what I do I never quite know what to say!”

The Pretenders leader talks songwriting with an unplugged electric guitar, the evolution of punk and her stunning new Fender signature Telecaster

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The trailblazing founder, vocalist and guitarist of the Pretenders Chrissie Hynde lives a life less ordinary, and yet even she succumbed to the rhythmless ennui of our pandemic present and, like many of us, welcomed a puppy into her home and took receipt of a new electric guitar.

And to think her 2020 was going to be big. The Pretenders’ new album, Hate for Sale, was scheduled for late spring, the first to be co-written with lead guitarist James Walbourne and feature the current touring lineup.

Stephen Street was returning as producer, having worked with Hynde on 1994’s The Last of the Independents, the following year’s live acoustic album The Isle of View, and 1999’s ¡Viva El Amor!, and Hynde’s calendar was booked out, with some 70 cities on the Pretenders’ touring itinerary.

Yadda yadda yadda, everything got paused and everyone was cocooned in the prophylactic amber of public health measures. Hate for Sale ultimately got released in the summer – they couldn’t sit on it any longer – but Hynde’s year was largely spent painting at her London home, sheltering in place.

Having moved from Akron, Ohio, to London in the '70s, principally because she wanted to see the world, because she likes to keep moving, this was an alien state to contend with.

“I like even the feeling of moving,” she says. “For me, getting in a band has been very much a vehicle to do that, just to keep moving, new cities, new countries, new places. It just turns me on.”

The puppy and the electric guitar both play their part today. Firstly, the guitar is the reason Fender have patched the call through – a signature model for Hynde is a big deal – while the puppy’s bladder capacity will determine how long we have on the phone.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

While we can’t bring you the spec on the puppy, we can say that of all the new year releases, Hynde’s signature Telecaster is sure to be shortlisted for Best in Show. It’s a production line replica of her 1965 Iced Metallic Blue Telecaster, the one you will have undoubtedly seen her with over the decades, her number one guitar since buying it in NYC circa 1980.

With a Faded Ice Blue Metallic color coated in Fender’s Road Worn lacquer finish, Hynde’s 2021 signature model has those city miles priced into the build, and it just goes to show that, like a pair of Levi’s, the Fender Telecaster only gets better with age.

If the Telecaster is the acme of the workhorse electric, the go-to instrument for blue-collar players, the chrome mirror pickguard and finish on Hynde’s Tele would suggest that there should be a union card registered to a Motor City automobile plant tucked inside the case. That’s the vibe.

I’ve bought a few guitars and then I have gotten them onstage and they don’t feel right, and then you go back to old faithful

It has a bound alder body, a bolt-on maple neck in a mid-'60s C profile and a rosewood ‘board in a rhythm guitar friendly 7.25” radius. There are two '50s voiced single-coil pickups and a six-barrel saddle bridge of stainless steel that is a guarantor of old-school twang without some of the old-school intonation funkiness.

Locking tuners replace those found on the original but otherwise, it’s an exact replica, with the Road Worn treatment on the hardware making sure the cuffs and collar match.

It might have been her guitar tech, David Crubly, that finally persuaded Hynde to consent to a signature model, but she explains here, now she has it, it’s going to have to put a shift in on the road like everyone else, when that fateful day comes… “Absolutely,” says Hynde.

“I’d take it now. They are almost identical. In fact, I’m looking at the new one, the one they made me, and I cannot even tell the difference. There’s no touring scheduled. We are in a holding pattern. But I would absolutely take this out.”

Out of all the guitars you could use, what has made the Telecaster stick for you?

“I tried a few different guitars and I ended up with that, and just really dug it, so I just stuck with it. It felt good. I liked the sound.”

And they wear in well. They only get more comfortable over time.

“I suppose any guitar does, yeah, and that’s why people keep going back to the same guitar, because they like the feel. I have tried some other guitars – and I get real excited about it. Like, ‘Right! Let’s pull that one out!’

“And then halfway through a song I will signal to my guitar player, grab my guitar and just take it off in the middle of the song and get rid of it… The neck isn’t right, something’s wrong, it doesn’t sound right. Sorry! That one is just consigned to the lock-up and I don’t even look at it anymore. I’ve bought a few guitars and then I have gotten them onstage and they don’t feel right, and then you go back to old faithful.”

How important is the guitar to your songwriting process?

“Songwriting is a funny thing. I wrote my early songs on an unamplified electric guitar so that I didn’t disturb the person in the next room, and yeah, every time you write a song it is different.

“I don’t think of myself as a songwriter. I don’t think of myself as a guitar player, either. In fact, if I have to write out on a form what I do I never quite know what to say. I am in a band; that is all I can really say about it. I do what has to be done to stay in the band.”

An amplified electric guitar is a funny thing. Do you think that with you having to hit the strings harder to make them audible that it has given you a more percussive style?

“I don’t know what my style is. I get the job done! When I first went into the studio to record my first record, I had to be playing an unamplified electric guitar when I sang, just to stay in the pocket. I couldn’t even sing without playing the guitar at the same time ‘cos I was so used to doing it that way.

“I would have it unamplified – obviously, so it doesn’t go down the vocal mic – but I would have to be playing along just to stay in time. The rhythm and the vocals very much went hand in hand. That was a very long time ago. I can go in now without the guitar.”

The secret to my success is that I have surrounded myself with people who are better than me. But I have an ear. I have a good ear, I guess, to know what everybody else should be doing

But it works. Your rhythm style is unquestionably yours.

“It was probably from playing with myself, not in a band. Because I did that for a long time. When I first got in a band, on my first album, somebody said, ‘Well, that’s not it. You dropped a beat there.’ And I said, ‘That’s the only way I know how to do it.’ So I had to find some people who knew how to play it the way that I heard it. I wouldn’t say I developed it. It is almost like I had it developed.”

And that approach to the rhythm, that’s the secret sauce in the Pretenders’ sound, like a thumbprint.

“I guess. I don’t know… I just do what, hmm, I’m not sure.”

Do you think it is the sort of thing that if you overthink it, it takes the magic away, like it kills the idea?

“I am already overthinking it! So, yeah. I’m not sure. [Laughs] It is what we do, and I guess the whole point of playing in a rock band is that you're not thinking. You're just doing something. I can’t speak for anyone else, though.”

And then your sound with the Pretenders is so lush and rich, there’s a lot going on there…

“Ah, well that is down to my guitar players in the band, and I kind of orchestrate it. I know what I want it to sound like. The secret to my success is that I have surrounded myself with people who are better than me. But I have an ear. I have a good ear, I guess, to know what everybody else should be doing.”

If you were coming from a punk background, James Honeyman-Scott was the perfect fit for adding the melody on top of all that.

“Yeah, Jimmy didn’t like punk. He thought it was too angry. He liked melody.”

What drew you to punk?

“Well punk was more about getting rid of prog rock. Punk was made by a bunch of kids who couldn’t really play good. That was when I thought I was too old to get into a band. When punk started, I must have been coming up for about 25, and at that point, traditionally, I was too old to get in a band. I mean, the Beatles had broken up by the time they were 29. It was a different world.

“What characterized punk for me was that it was very much a non-discrimination thing. Having said that, they were also obsessed with it being working class, as the English always are.

“The class system figured into it but I couldn’t relate to that. I didn’t know what the class system was. But certainly, maybe being a couple of years too old, being a girl, all these things were going to figure into the punk thing because it wasn’t part of the punk conversation. That’s when I thought I could sneak in there.”

Well punk was more about getting rid of prog rock. Punk was made by a bunch of kids who couldn’t really play good

And your tastes soon evolved?

“Punk wasn’t necessarily very musical, and that’s where I didn’t really fit into a punk band, because I grew up on American radio; I probably had kind of a more diverse background to most of my punk colleagues who grew up on Mott the Hoople and Van Der Graaf Generator, or whatever they were listening to.”

You’ve played with some phenomenal players. What do you look for in a guitarist?

“Well, they just have to look the part and play great, y’know. You know immediately, just by the way they hold the guitar, just by the way they walk down the street. It is more than just the playing; it is the general sensibility. Not many people have it.”

James Walbourne is similar to James Honeyman-Scott in a sense. He, too, can play anything, and he has a keen ear for melody…

“Absolutely. He is a natural successor to Jimmy. He’s got a very similar sensibility in what he likes, in his sense of melody.”

Do you play much at home?

“Yeah, sometimes, not so much. I paint at home. I am very quiet at home. And I don’t have a studio or anything.”

What do you play through when you are at home?

“Nothing. And that’s mainly how I wrote all my songs at first because I didn’t want to disturb anyone. I’ll sometimes have an acoustic guitar. I don’t have one here at the moment, but that would be another go-to for writing.”

One thing we have a lot of at the moment is time. Have you done any writing?

“Yeah, I have. We have about half an album done, written remotely. I was going to be in 70 different cities last year and I wasn’t in any, so obviously it freed me up to do things I never had time for. I have listened to [BBC] Radio Three and heard classical musicians say the same thing – no performing is a drag, but people have gotten on with things they didn’t have the time for.

“That is going to eventually get frustrating but, remember, it has only been year. It is not like there has been five years of this. James and I are going to go in and start trying to get in a rehearsal room and just play a little bit, because it is getting frustrating.”

For more information on the Chrissie Hynde Telecaster, head to Fender.com.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to publications including Guitar World, MusicRadar and Total Guitar. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.