How Chuck Berry wrote Johnny B. Goode, and created the first rock and roll guitar hero

In his 1958 masterpiece, Berry created the ultimate rock-and-roll folk hero in just a few snappy verses

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This is an excerpt from Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound & Revolution of the Electric Guitar by Brad Tolinski and Alan di Perna.

In 1954, at the age of 41, blues musician Muddy Waters had finally made it to the top. Or so it seemed.

Hoochie Coochie Man and I Just Want to Make Love to You, released that year, became his biggest sellers and remained in the Top 10 R&B charts for more than three months. But the winds of change were blowing, and that summer blues record sales suddenly plummeted, dropping by a dramatic 25 percent and sending shock waves through the Chicago music industry.

Record execs blamed the poor economy, but a fresh and more youth-oriented brand of music was starting to sweep the airwaves, one that was built on the bones of the very R&B, blues and country that they had so carefully nurtured. As Waters would later sing, “the blues had a baby and they named it rock and roll.”

In ’54, Elvis Presley paired the country tune Blue Moon of Kentucky with That’s All Right, a song originally performed by blues singer Arthur Crudup, and the single sold an impressive 20,000 copies. That same year, Bill Haley & His Comets sold millions with Shake, Rattle and Roll and Rock Around the Clock. In response, Leonard Chess of Chess Records sniffed out and signed two young electric guitar–playing rockers of his own.

Bo Diddley and his rectangular guitar would become an enormous commercial success; but it was Chuck Berry’s crossover to the white teenage market that would make him a legend.

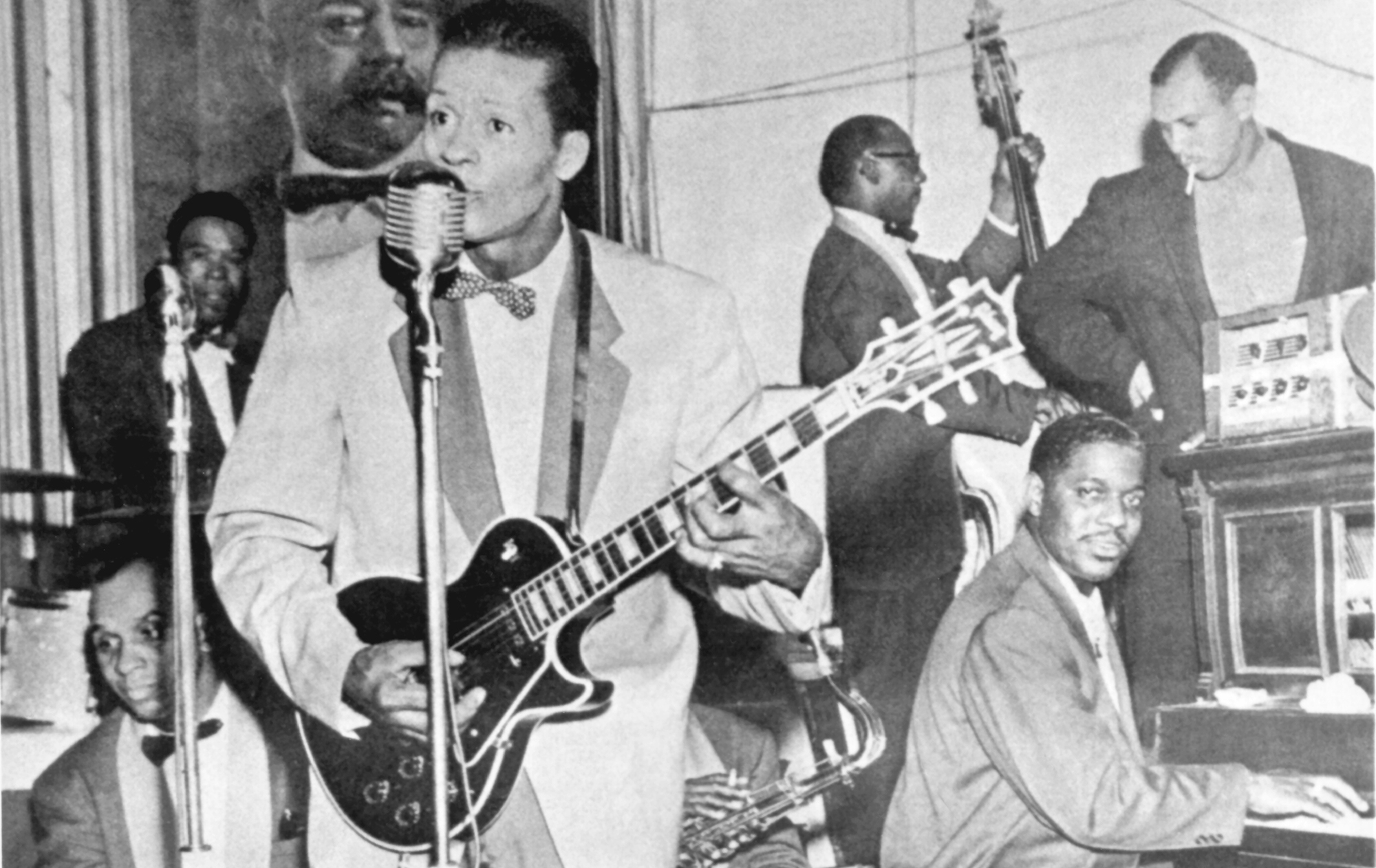

Charles Edward Anderson Berry, born to a middle-class family in St. Louis in 1926, was a brown-eyed charmer who loved the blues and poetry with almost equal fervor. After winning a high school talent contest with a guitar-and-vocal rendition of Jay McShann’s Confessin’ the Blues, he became serious about making music and started working the local East St. Louis club scene, where he put all of his skills to good use.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

While Berry excelled at playing the blues of Muddy Waters and crooning in the suave manner of Nat King Cole, it was his ability to play “white music” that would eventually make him a star.

“The music played most around St. Louis was country-western and swing,” Berry said in his autobiography. “Curiosity provoked me to lay a lot of the country stuff on our predominantly black audience. After they laughed at me a few times, they began requesting the hillbilly stuff.”

The sight and sound of a black man playing white hillbilly music, combined with Berry’s natural showmanship and his ability to improvise clever lyrics to fit any occasion, made him a top attraction with Missouri’s black community. But Berry had bigger aspirations; he wanted to make records.

While on a trip to Chicago he paid a 50-cent admission fee to see his favorite blues singer, Muddy Waters, perform, and after the show he worked his way toward the bandstand and managed a few words with his idol.

"It was the feeling I suppose one would get from having a word with the president or the pope,” Berry remembered. “I quickly told him of my admiration for his compositions and asked him who I could see about making a record.”

Waters told the guitarist to see Leonard Chess. So, taking his hero at his word, Berry made a beeline for Chess Studios the next morning, introduced himself to the receptionist, and politely asked to see Chess. Remarkably, Chess waved him in, and Berry passionately delivered a well-rehearsed speech outlining his hopes as a musician.

“He had a look of amazement that he later told me was because of the businesslike way I talked to him,” Berry later said. Hearing Chuck’s homemade demo tape, the label president gravitated to a cover of Ida Red, a 1938 song made popular by country swing band Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys.

Chess recognized the crossover potential of a black artist playing country music, and he scheduled a session for May 21, 1955. After all, if a white man like Presley could make hit records by sounding black, why not try the reverse? During the session, Chess demanded a bigger sound for the song and added bass and maracas to Berry’s trio. He also told Berry to write new lyrics, insisting that “the kids want the big beat, cars and young love.”

Chuck quickly responded with an outrageous story about a man driving a V8 Ford, chasing his unfaithful girlfriend in her Cadillac Coupe de Ville. The title was changed from Ida Red to Maybellene, a name inspired by a brand of makeup teenage girls were wearing at the time. Although the record only made it to the mid-20s on the Billboard pop chart, its influence was massive in scope.

Here was a black rock-and-roll record with across-the-board appeal, embraced by white teenagers and Southern hillbilly musicians alike (including Elvis Presley, who added it to his stage show). And it was fortunate for the electric guitar that one of its earliest champions was not only an extraordinary musician and showman, but also one of pop music’s greatest and most enduring singer-songwriters.

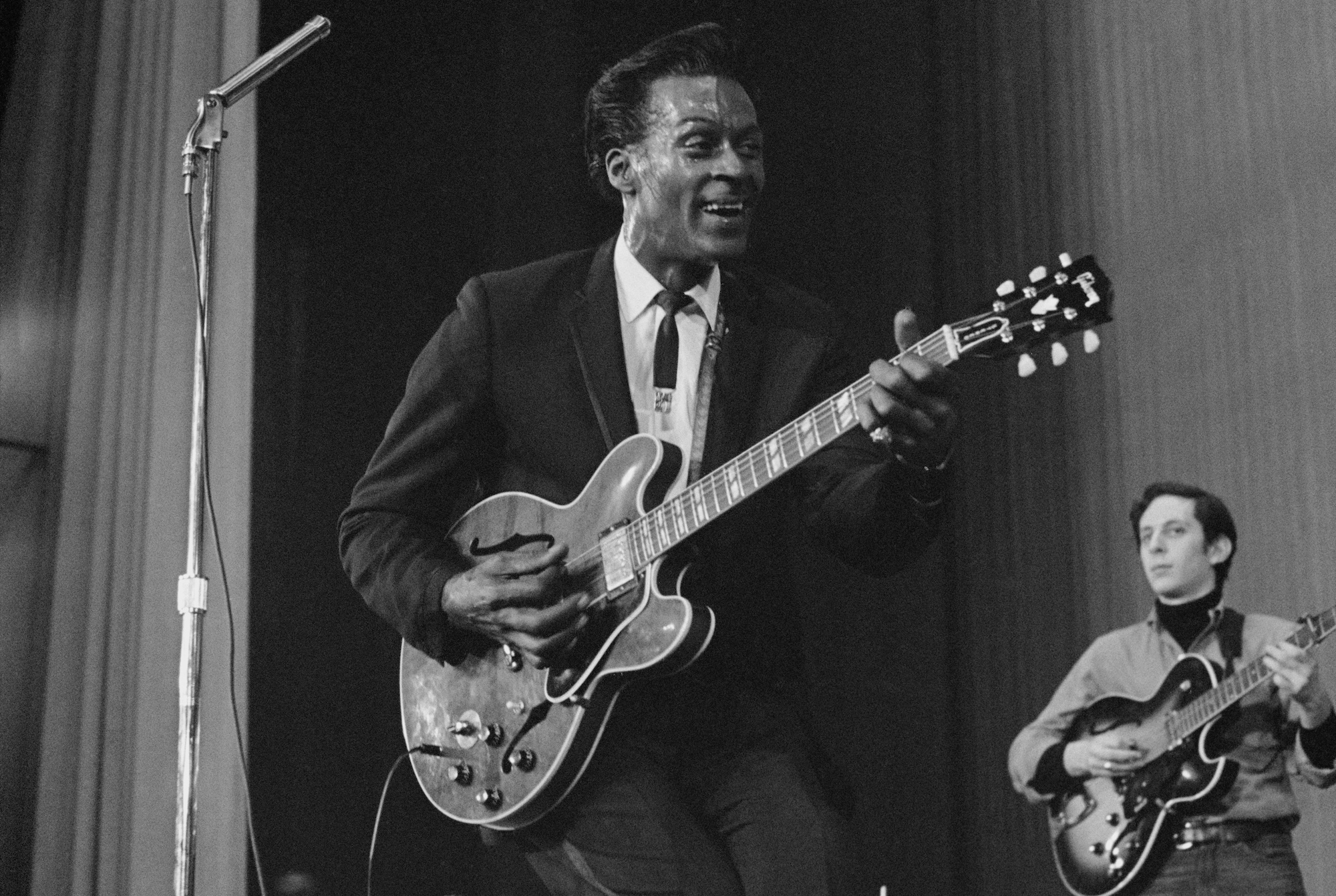

With monster hits such as Roll Over Beethoven (1956), Rock and Roll Music (1957) and Sweet Little Sixteen (1958), Chuck Berry did much to forge the genre. His formula was ingenious: write lethally funny lyrics about the teenage experience, strap them into a high-octane groove, add a little country twang, shake it up with a showstopping guitar solo, and then watch the acclaim pour in.

It was a recipe that would dominate popular music for decades to come. And if early listeners didn’t understand how important his guitar was to the mix, Chuck soon made the connection explicit.

In his 1958 masterpiece Johnny B. Goode, Berry created the ultimate rock-and-roll folk hero in just a few snappy verses. As we all know, Goode wasn’t pounding a piano, singing into a microphone, or blowing a sax. In his choice of the electric guitar, something sleek and of the moment, the fictional character of Goode would forge an image of the archetypal rocker, doing as much to shape the history of the instrument as any real-life figure ever has.

The song’s opening riff is a clarion call – perhaps the greatest intro in rock-and-roll history. It was played by Berry on an electric Gibson ES-350T, and it indeed sounded “just like a-ringin’ a bell.”

The tale begins “deep down in Louisiana,” where a country boy from a poor household is doing his best to get by. Johnny, we discover, “never ever learned to read or write so well,” but he has something better than a formal education or a diploma – he has talent, street smarts, and a guitar.

Johnny’s Gibson is his instrument and also his ticket out of the backwoods. After introducing our hero, the anthem turns to his guitar. It’s portable – he could toss it into a “gunnysack” and practice anywhere, even beneath the trees by the railroad. It’s astonishingly loud. More powerful than a passing locomotive, Johnny’s soaring notes stop train passengers dead in their tracks.

By the last verse, the guitarist’s reputation has spread far and wide. As his growing legion of fans and supporters cheer him on with shouts of “Go, Johnny, Go,” even his long-suffering mother is forced to concede “maybe someday your name will be in lights.”

Johnny B. Goode is a brilliant, uniquely American rags-to-riches story, but with a modern twist. Where Horatio Alger’s nineteenth-century heroes rose from humble backgrounds to lives of middle-class security through hard work and virtue, Goode excelled on his own terms; he was uneducated, solitary.

He was a bad boy, a story line all the more compelling to a generation of teenagers just beginning to identify with outsider icons such as James Dean and Elvis Presley. It was a song that thrilled and exhilarated audiences both black and white.

It became a massive crossover hit, peaking at Number 2 on Billboard magazine’s Hot R&B Sides chart and Number 8 on the Billboard Hot 100. To teenage ears, Chuck’s guitar signaled the dawn of a new era.

The glorious peal of his 350T proclaimed that school was out. John Lennon, Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, Keith Richards and Bruce Springsteen were just a few of the working-class kids who immediately grasped the sly moral of the song, and who recognized a good blueprint when they saw one.

“I could never over-stress how important [Berry] was in my development,” said Richards, perhaps the ultimate rock-and-roll outlaw. Reflecting on the significance of Johnny B. Goode and his other hits, Berry later played down his originality. He was attempting to marry the diction of Nat King Cole, the lyrics of Louis Jordan, and the swing of jazz guitarist Charlie Christian, but with the soul of Muddy Waters.

“Ain’t nothin’ new under the sun,” he was fond of saying. But he was being modest. His synthesis of genres and his use of amplification were wholly original.

If Christian introduced the electric guitar to a mass audience, Berry created its grandest mythology. As the electric guitar began to take on its signature shape in the Fifties – almost indistinguishable from the guitars of today – it bears noting how conspicuously sexy that design had become.

With curves that cartoonishly mimicked the lines of a woman’s hips, and an undeniably phallic neck, the guitar may have preceded the sexual revolution of the Sixties, but it would become a perfect visual complement to it. Its provocative design was something Berry was one of the first to acknowledge, and that he rarely failed to exploit in his live shows.

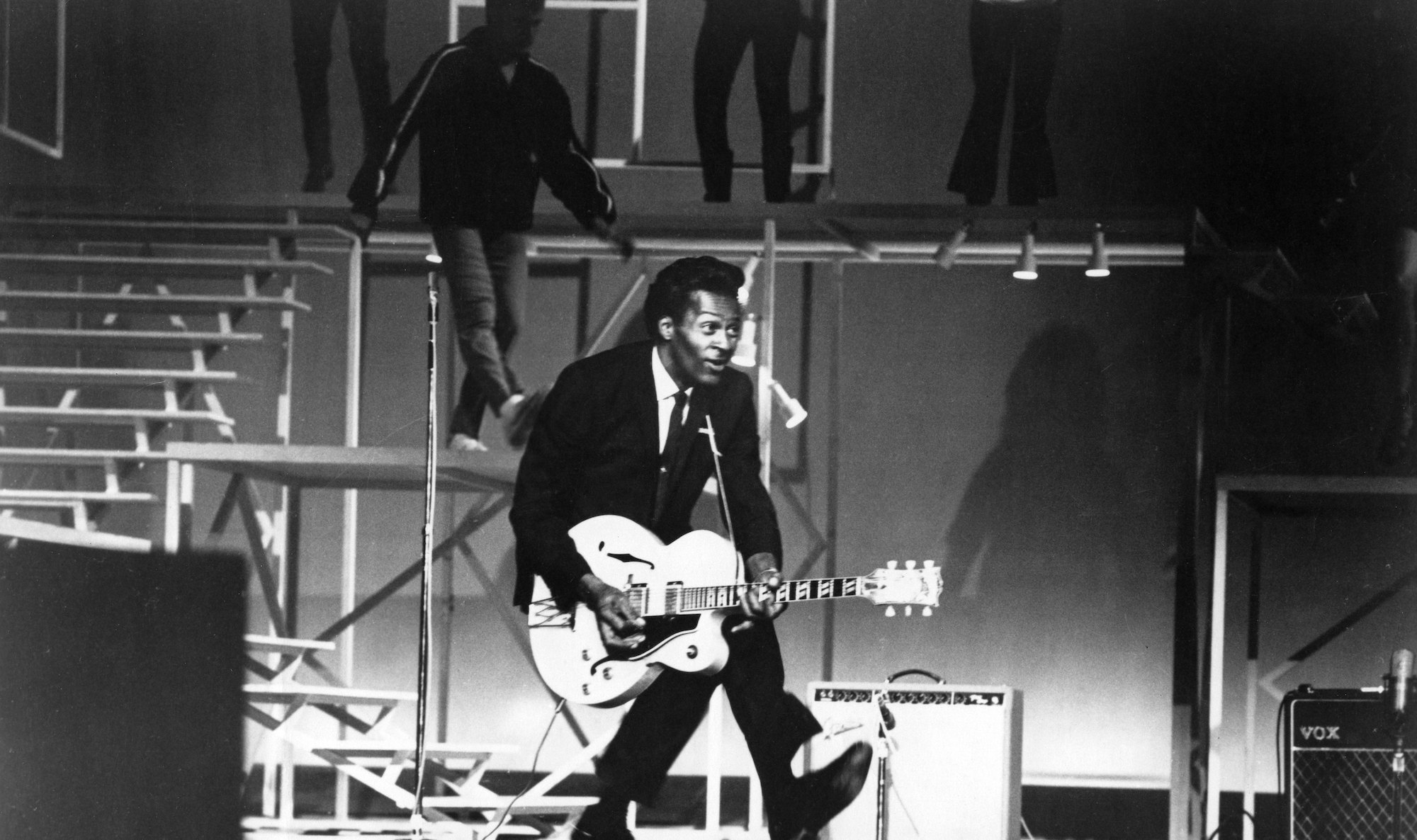

While he had to be careful with how far he went – Chuck was one of the first black crossover rock-and-roll artists in a very racially charged time – he wasn’t that careful. He often played to predominately white audiences at rock-and-roll stage shows booked by DJ/promoter Alan Freed, or in Hollywood films such as Rock, Rock, Rock!, Go, Johnny Go! and Mister Rock and Roll.

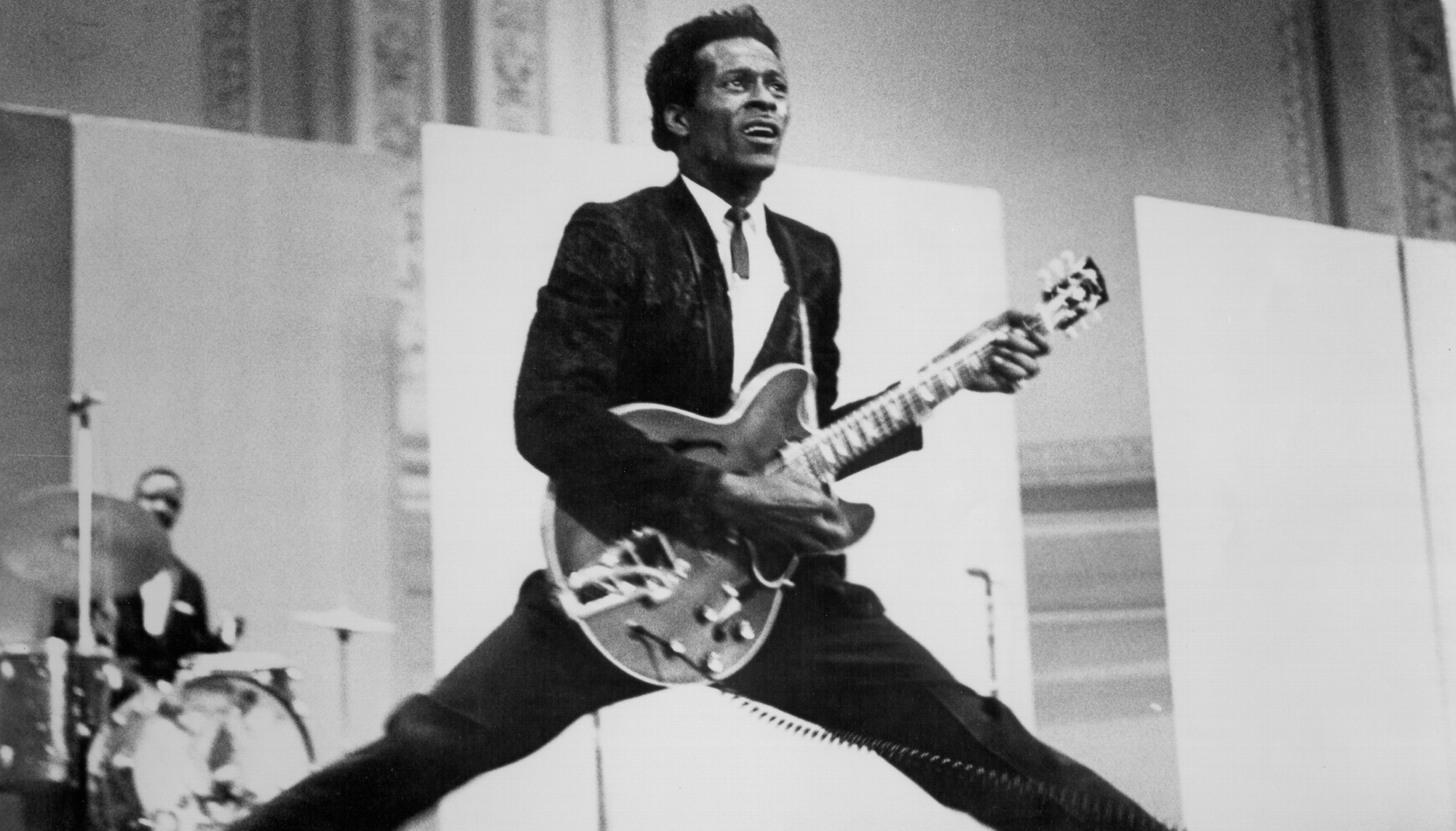

During each appearance, Berry would kiss his Gibson or Gretsch on the neck, wrestling with it as he made it scream and swoon during his wild solos, jutting it lasciviously from his waist as he did splits. The Gibson ES-350T was particularly well suited to Berry’s gyrations.

In the mid Fifties, electric guitar players had two choices: either a full hollow-body or a compact solid-body. Gibson had been receiving requests from players for something in-between the two styles, so in 1955 their first “thinline” electrics were developed.

The guitar’s medium build was a perfect fit for Chuck’s high-energy stage presentation. Chuck’s guitar antics and wild gyrations were provocative stuff for suburban kids, who were used to gently swaying crooners such as Frank Sinatra or Rosemary Clooney. And while they might not have understood all the implications of his act, one thing was clear: the electric guitar presented a seriously dangerous, sexy alternative to the comparatively staid piano or the sax.

At the end of the Fifties, dozens of guitar-playing Johnny B. Goodes appeared, irrevocably changing the musical landscape, all playing in small electric combos resembling those pioneered by Chuck Berry and Muddy Waters.

As for Waters, he had a few more hits, including Mannish Boy in 1956 and She’s Nineteen Years Old in 1958. But the music of a 40-something guitarist like Muddy was being overtaken by rock and roll, driving him back into the small blues joints from whence he came. As Waters ruefully noted, “[Blues] is not the music of today; it’s the music of yesterday.”

Little did he suspect that a few short years later, his music (along with that of younger acts such as Berry and Elvis) would find new life across the Atlantic, where it would be discovered by and inspire a generation of white British teens.

They would go on to pick up electric guitars and start blues and rock bands of their own. The Rolling Stones (who borrowed their name from a Waters song), the Animals, the Yardbirds, Cream and Led Zeppelin would pay homage – not to mention royalties – to those pioneers. Blues played on electric guitars, it turned out, was far from the music of yesterday. Indeed, it would be the music of today for decades to come.

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away Brad was the editor of Guitar World from 1990 to 2015. Since his departure he has authored Eruption: Conversations with Eddie Van Halen, Light & Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page and Play it Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound & Revolution of the Electric Guitar, which was the inspiration for the Play It Loud exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 2019.