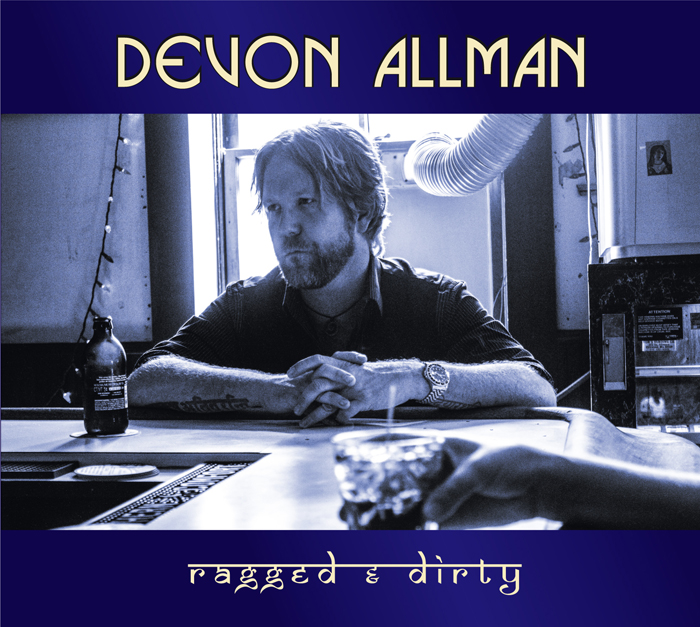

Devon Allman: 'Ragged & Dirty' and Loving It

On one hand, you can say Devon Allman comes by his musical talents naturally, being Gregg Allman’s son.

But the fact of the matter is, Devon’s parents were divorced when he was a baby—and he was brought up in a world that was well-insulated from the savage highs, lows, glories and turmoils of the Allman Brothers Band.

As you’ll read below, Devon’s musical interests developed organically. Translating his passion for the music he was listening to on the radio into garage band roar, Devon was already forging his own sound by the time he met his famous father. And though their musical and personal paths have crossed over the years since, Devon’s path is truly his own, along with his sound, style and career.

Most interesting may be Devon’s evolution as a guitar player: Though he first strapped on a six-string in his early teens, he was into his thirties before circumstance inspired him to get serious about his lead playing (as he explains in our conversation that follows).

Devon’s latest solo album, Ragged & Dirty, is a solid showcase of his talents—from powerful, soulful vocals to dig-in-and-let-fly guitar work. Working with producer (let alone killer drummer) Tom Hambridge, Allman has crafted a collection of tunes that spans the gamut from shake-the-speaker-out-of-the-dashboard rock roar to starlit blues jam. His originals nestle comfortably alongside covers such as the Spinners’ “I’ll Be Around” and Otis Taylor’s “Ten Million Slaves."

Allman and his core band of bassist Felton Crews, Marty Sammon on keys and guitarist Giles Cory cover a lot of ground over Ragged & Dirty’s dozen tracks—but every inch is a natural fit.

Devon’s insistence that Bobby Schneck Jr. (who plays guitar in Devon’s current touring band) take a fat-toned lead on the cut “Leavin’” tells you a lot about the man. “It’s my duty to let the younger players be heard,” he told me. “That’s how this is supposed to go, man.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Meet Devon Allman—funky, soulful and real as hell.

GUITAR WORLD: Devon, what music really grabbed you as a kid?

I was listening to Seventies rock radio; it’s called “classic rock” now, but it was cutting edge then. I was very much into Santana, the Beatles, the Stones and the Doors, you know? Eventually, I branched out into other stuff: hardcore blues, heavy metal, jazz, alternative … everything. Once I started to play guitar, I wanted to hear all the different styles: “I want to hear this guy play it this way …”

Was the guitar the first thing you picked up?

I actually started on violin, and I was horrible, man. [laughter] Truly horrible … but it didn't last long.

How old were you?

11, I think. The guitar came at 13.

I’m guessing you didn't pick up the violin on your own.

It was forced onto me, bro … it was forced onto me.

But you reached out for the guitar.

I did, yeah. I went to my buddy Jason’s house one day after school—eighth grade. I saw this guitar in the corner of his room, and I said, “Dude, you play guitar?” And he was, like, “Oh, yeah, man … I can play.”

So I said, “Play it, then.”

He picked it up and fumbled his way through a Def Leppard song or something. And in my mind, I was thinking, “This is horrible …” [laughter] But it was the first time I'd ever watched someone play from just a few feet away, you know? And I thought, “I can do that.”

I went home and said, “Ma, I want to play guitar.”

And what could she say?

Well, the thing was, she’d actually tried to get me to play guitar from the age of 5 or 6; tried and tried but I just didn't have any interest. I guess I didn’t think I'd be any good. When I came to her finally after seeing this kid play, she was ecstatic. She handed me her Mexican flamenco guitar that we had; she actually took lessons and played when she was a teenager.

Of course that was impossible to play—the catgut strings, the baseball bat neck—but she said, “If you get good enough on this, I’ll buy you an electric guitar. I learned some tunes; she was impressed; and I had an electric guitar in, like, a month.

And that first electric?

A piece-of-shit Martin Stinger. [laughs]

A Stinger?

Yeah: a Strat body and it had an Eddie Van Halen paint job, or something close to it. I think I had that for six months before I got a B.C. Rich Strat body. That was my baby through high school. [laughs] We were all kids at one point. [laughter]

So once you started playing rather than just listening, how did that change things? Who were your guitar heroes early on?

Early on? Jimi Hendrix. Jimmy Page was right up there … Eddie Van Halen … all the guys from the Steely Dan records. The fact is, I really just picked up the guitar to have something to write songs with. I was just a rhythm player. I didn’t start playing lead until I was 32. I don't know … I was frightened of anything past the seventh fret.

I have to ask: Was part of it the Allman name? Was there an intimidation factor for you?

I don't think so … I mean, I was a singer out of the gate. I was the only one in the garage bands when I was a kid that kind of had the balls to go to the mic and sing, you know? I thought I should spend my time becoming a better singer and rhythm guitar player.

What was the tipping point that got you playing lead?

In 2006, my band Honeytribe really hit the road hard and started touring all over America and Europe. And that’s when our lead guitarist hit me up with, “Hey, man, touring life isn't for me. I’m leaving the band. I love ya, but I can't do this.”

At that point, I was playing one guitar solo in the set per night, you know? It was a ballad; I could play really slow; I had this melodic, Santana kind of approach to it … and I really liked it. But it was the only one I really had any confidence in playing.

When he left, I was like, “OK, I can replace him, or I can try and play all the guitar solos.” I gave myself six months: “All right, practice your ass off for six months; if by then you’re not cutting it, be honest with yourself and hire a hotshot guitar player.” I think about two or three months into it, I had a really breakout night on stage where everything worked … I really got a lot of confidence from that. And that was it.

Listening to Ragged & Dirty, it’s obvious you have a wicked set of pipes. I’m thinking some folks who are new to your music might not realize that’s you doing the leads, because your voice is so damn strong.

Aw, man—thanks.

No, it’s not a compliment; it’s a statement of fact. [laughter]

Well … thank you.

But you have your own thing going on. And to me, that’s the message about this album: it's your thing. Whether we’re talking about family or your influences over the years, you’ve made your own way with your vocal and your picking. Maybe it was better that you held off on lead playing until you were 32, you know?

And that’s the crazy thing. Everything happens for a reason: and there was a reason I didn’t grow up around my Pops, you know? I got to forge my own path through music organically and I wasn’t around the insanity that was happening in those days.

By not touching lead guitar until later on in life, I had a chance to become a good singer before I started worrying about guitar, as well … I got to take things in stages and really work at becoming a songwriter and a singer first.

I’m not a shredder, though; I wasn’t formally schooled or anything. It's all by touch and feel and ear. The thing is, I'd much rather be able to play five notes and have someone know who I am than play 50 notes really fast.

I’ll take heart over technique any day. Heart has its own technique.

You got it, man.

I think of you as a Gibson guy . Is that true on Ragged & Dirty?

Absolutely. I played Strats for years, but when I switched to lead guitar, I needed a thicker voice. I went to Gibson and within a year I signed an endorsement deal with them. I’ve been a loud, proud Gibson guy for a long time now. I did pick up a Strat for the instrumental “Midnight Lake Michigan” on this record. That’s a very Strat kind of thing.

So, the primary guitar for the bulk of the tracks was …?

The same one I’ve used for the last ten years. A ’59 Cherry Sunburst Les Paul, a Custom Shop Historic that Les Paul himself signed. That’s been my baby for 10 years. It's on probably 80 percent of the record, and it’s what I play on stage most of the time.

And how about amps on this album?

You know, I’m an endorser of Fuchs; they released a Devon Allman signature amp a few years back. That’s my live rig that I’m so proud of. But for this record—believe it or not—all of my leads were done on a 15-watt 1x12 Victoria. Every single lead was done on a little tiny amp.

I remember when I discovered the secret to Duane and Clapton’s sound on Layla years ago: Fender Champs. Little pisspot amps that sounded as big as the world.

Absolutely, man. If you mic it right and throw a mic into the room to catch the ambience, you can mix the two. It doesn't take volume in the studio—it takes tone.

You tap into some effects along the way but you don't rely on them a lot on this album. There is one tune, “Traveling,” where you do some really tasty wah work. Who’s your wah hero?

I think when I first started playing lead, I leaned on the wah quite a bit; it was something to hide behind. But now that I’m confident as a lead player, I use it a lot less … more for texture than a gimmick. I loved all the Hendrix wah stuff. That’s my go-to.

The one track I wanted to make sure we talked about specifically is “Midnight Lake Michigan”: nine minutes and 30 seconds of sultry blues guitar porn. There are a lot of players who would’ve dug into some go-to blues clichés in an instrumental that long, but you definitely find your own way as you go.

That’s my favorite track on the record, and it was the last thing we cut. We had the album in the can as far as the basic tracks.

I asked Tom, “Would you let me do a mood piece?”

And he said, “What do you have in mind?”

I told him I wanted to do a slow, spooky blues in B minor; just have the band percolate, slowly boil on the I, like, forever, like a Coltrane thing. I said, “Let me lead the band and when we get to a certain point, I’ll give the signal and we’ll go from the V to the IV and then drop right back down to the I. We’ll hold that pattern and repeat it, running through it three times. It’ll be, like, 10 minutes long.”

Tom thought the record was strong enough where this would be a really cool artistic statement. “Let's do it,” he said.

We went in there, played it once—and that was it.

Really?

We didn't play it a second time. What you hear is completely live; the only overdub is Marty going back to put some spooky, percussive piano wire stuff. Everything else is totally live.

I appreciate you saying I didn't fall into any blues clichés, as I wanted to do an instrumental without doing a main head; a main melody. I wanted it to be spooky and open-ended and let it land where it wanted to land.

And that’s what it feels like: Here’s the empty wall and you’re coming in and splashing on the colors as you see fit.

Definitely—a Jackson Pollock approach. [laughs]

So why the Strat on that one?

You know … I really don't know. [laughter] I guess because I wanted the guitar to talk, you know? You can make a Les Paul sing—that violin-like, woody tone—but you can make a Strat talk.

Well, as I said earlier: that tune, and this album as a whole, is such a great example of you having your own thing going on. I mean no disrespect to the family name.

I hear you and I appreciate that. I think at the end of the day, that’s not disrespectful – I think it’s the most respectful thing to my family to have made my own way and made my own name. Sure, the music falls in the same category – the same genre - but you really do have to be your own person; you have to do your own work; you have to make your own art.

To have a personal stamp on it has always been my goal … and I think it does my family proud to have that.

If you were a cook, I’d tell you not to mess with the recipe.

[laughs] Thank you, man—thanks so much.

A former offshore lobsterman, Brian Robbins had to wait a good four decades or so to write about the stuff he wanted to when he was 15. Today he’s a freelance scribe, cartoonist, photographer and musician. His home on the worldwide inner tube is at brian-robbins.com (And there’s that Facebook thing too.)