“Once in a while, we would start playing a Beatles song, and John would go, ‘Cut that out!’” Session guitar legend Earl Slick on fast times with John Lennon and David Bowie – and saying no to Whitesnake

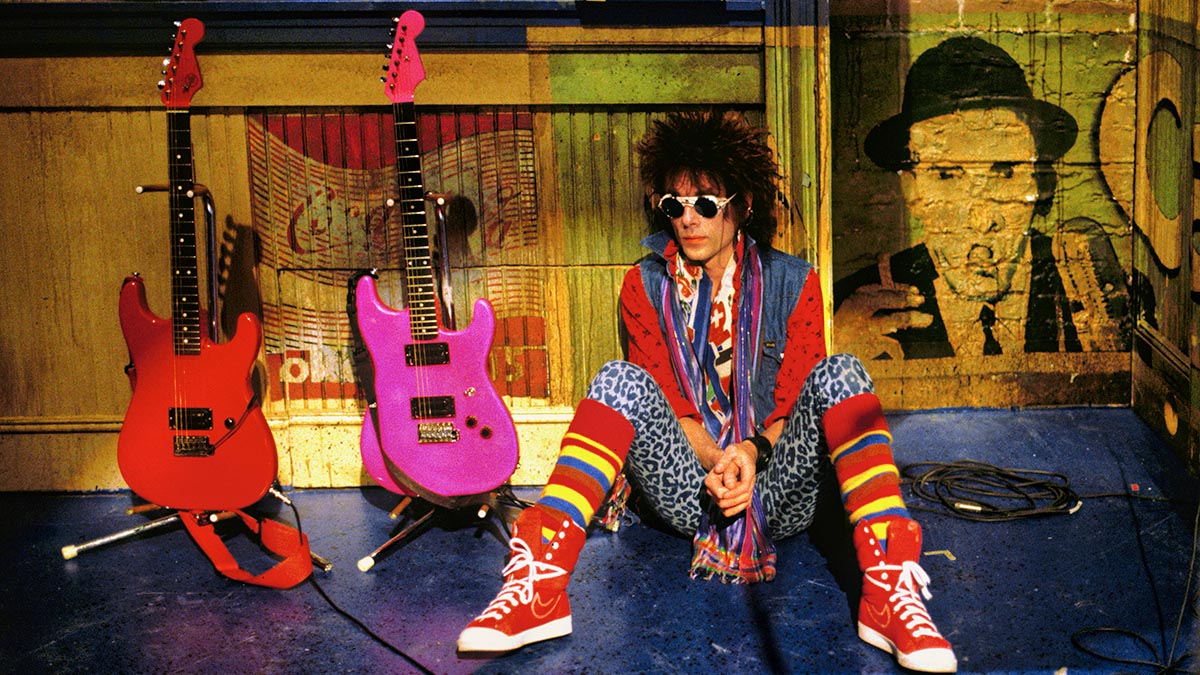

Throughout the ’70s and into the ’80s, Earl Slick was living most rock ’n’ roll guitarists’ dreams. He’d logged several worldwide tours with David Bowie and played a vital musical role on albums such as Young Americans and Station to Station.

As if working with one British rock legend weren’t enough, in 1980 Slick was chosen by John Lennon to play guitar on the former Beatle’s first album in five years, Double Fantasy.

“That’s just the tip of the iceberg,” Slick says. “I was really, really busy back then. There are days now when I astonish myself going, ‘Christ, did I really do all that?’ I’ll go on Wikipedia and be like, ‘Oh, there’s this and that.’ Or somebody will call and say, ‘I was just on Spotify and you’re on this record.’ I’ll say, ‘Now that you mention it, I am. I forgot about that one.’”

By the mid-’80s, however, the high-profile gigs weren’t coming like they used to. Slick attempted a career reboot with ex-Stray Cats members Slim Jim Phantom and Lee Rocker in Phantom, Rocker & Slick, but their union lasted for only two albums.

After kicking a debilitating drug and alcohol dependency, he joined the L.A..-based glam-metal band Dirty White Boy, who went belly-up after one album. A short stint with another L.A. outfit, Little Caesar, yielded similar results. Finally, in 1992, fed up with beating his head against the wall, Slick decided to chuck it all and headed to Lake Tahoe. For the next four years, he pursued a “normal job” selling timeshares.

“Only problem was, I sucked at it,” he says with a laugh. “I was no good at it at all. It was a strange time – I was adjusting to being sober, and I was filled with anxiety and discouragement from being jerked around by record companies. I just thought, ‘I need a drastic change.’ So I went somewhere I could be anonymous and get away from it all.”

In an unlikely turn, Slick was tempted to ditch retirement by a Tahoe neighbor, Whitesnake singer David Coverdale, who floated an offer for the guitarist to join the veteran hard rock band.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I gave it some serious thought, but I finally had to say no,” Slick says, “I realized I would have been faking my way through it, and it would have backfired on both of us.” More to the guitarist’s liking was a six-month writing collaboration with Coverdale that resulted in the singer’s third solo record, 2000’s Into the Light.

After recording the album, Slick still wasn’t convinced that he was ready to return to music full time. That all changed in 1999, when he received a vague and bewildering email indicating that somebody was looking for him. Some amateur sleuthing revealed that the somebody was none other than David Bowie. “I contacted David, and before you knew it I was back in,” Slick says.

Over the next 14 years, Slick played with Bowie on Heathen (2002), Reality (2003) and The Next Day (2013) and toured with the singer until 2004 (after suffering a mild heart attack on stage in Prague, Czech Republic, during the Reality Tour, Bowie was forced to cancel his remaining dates and never resumed full-time performing).

Meanwhile, the guitarist released solid solo albums (2002’s Slick Trax, 2003’s Zig Zag and 2021’s Fist Full of Devils), toured with the New York Dolls and the Yardbirds, as well as a band called Slinky Vagabond (which included the Sex Pistols’ Glen Matlock and Blondie’s Clem Burke).

Recently, Slick was reunited with various Bowie alumni (among them pianist Mike Garson, guitarist Mark Plati, bassists Gail Ann Dorsey and Tim Lefebvre) on a new band project, KillerStar, spearheaded by singer Rob Fleming and drummer James Sedge. The group recorded an album’s worth of material remotely, and there are plans to perform live.

Thus far, only two tracks have been released – the faintly Bowie-esque Should’ve Known Better blends classic rock and art rock, while Falling Through bears traces of prime Pink Floyd – but Slick isn’t sure which is which.

“I don’t know titles, really,” he says. “I don’t even know half of the Bowie titles I’m on except the hits. But I had fun doing the KillerStar stuff. It seemed like a good opportunity, and it turned out well. Technology is amazing; I can do all this recording without leaving home.”

I’m going to jump around a bit, but I wanted to start by asking you about Mark Plati. You two worked on some of David Bowie’s early 2000s records, and he produced your album Zig Zag. How do you two bond guitar-wise?

“We get on great. He’s a terrific guitar partner, but then he does everything. He’s a motherfucker of a rhythm player. He doesn’t just get the parts down – he gets the feel. Whenever we played together as a guitar team, if he was playing rhythm, I didn’t have to think about anything. It was great.”

Mike Garson is also on the KillerStar album with you. What do you remember about playing with Mike on Young Americans?

“My recollections are vague. Out of all the stuff I did with David, I have a memory block about Young Americans, which doesn’t make sense because we were far more fucked up when we did Station to Station. On that record, we went in and we stayed there until we finished everything. With Young Americans, we did maybe a week of sessions and then we were back on the road. It wasn’t one continuous job, per se.”

Tony was there and he kept things organized, but the creative ideas, when it came to me, that was David. It was the same way with Harry Maslin and Station to Station

Even with your vague memories of Young Americans, can you speak to the differences in working with producer Tony Visconti on that record versus Bowie’s later albums?

“I might as well just stick my foot in my mouth. One thing about artists like David Bowie – there’s a producer there, but when we worked on parts and stuff, all of that was David. Tony was there and he kept things organized, but the creative ideas, when it came to me, that was David. It was the same way with [producer] Harry Maslin and Station to Station; it came down to David. Most of it was the two of us working my shit out. Like on The Next Day, my favorite track is Valentine’s Day.”

Beautiful song.

“David played that for me in the control room on an acoustic the day we were going to cut it. As soon as I heard it, I said to him, ‘The Kinks’, and he went, ‘Great.’ If you notice, the rhythm guitars on that song are very Waterloo Sunset.”

That song has a memorable riff and a striking solo.

“Yeah, well, after I said ‘Kinks,’ I started to noodle around on some rhythmic things, and David said, ‘We need an opening riff and some other riffs.’ He would play a couple of notes, and I’d get an idea and develop it. Then I’d wait to see the smile on his face, and I’d think, ‘OK, now we got it.’ It never really took a lot of time.”

You mentioned Station to Station; that title track is so revolutionary, and your end solo is way out-there in terms of experimentation. Do you ever listen to it and go, “What the hell were we doing?”

“[Laughs] I mean, on the occasion when I hear something on the radio or I might play a few tracks, part of me is going, ‘Christ Almighty, we really did pull off some cool stuff together, and it was timely.’ In hindsight, it doesn’t sound that outside the box, but at the time we did it, I guess it was.”

Do you remember which guitars you used on it?

“On Station, I used a Strat on some of the rhythm parts; actually, on the first half, where it’s a little dirge-y. Then when it goes uptempo, I’m using my black Les Paul on the rhythm and also on that solo.”

What about on Stay? That’s another gem on Station to Station.

“The rhythm is the Les Paul, and the solo is the Strat.“

Both of those songs are so freeform; they feel like one-take keepers.

“Stay was pretty much a one taker. On Station, we sat down with a couple of guitars, and we wanted it to have a little bit more structure to it, a little bit more of a melodic thing, which Stay wasn’t – that was just going to be a bluesy kind of free-form solo. But on Station, we wanted something different, so we were just sitting there with a few guitars and coming up with different licks for each little bit.”

Back to Young Americans for a second, was that your first contact with John Lennon?

“It was, but I can’t remember it.”

Because you were high at the time?

“Well, yes, I was. This is so strange because John is my favorite Beatle.”

No memory at all of working with him on Fame?

“No, I can’t remember… So fast-forward to 1980. I was uncharacteristically nervous before Double Fantasy started. I went in early on the first day. I thought if I could grab a cup of coffee and a smoke and just chill out… I got to the studio and nobody was there – except for John. I introduced myself, and his reaction was, ‘Why?’ Because to him, we already knew each other. And I said, ‘Well… I don’t remember.’

“The second I said it, I thought, ‘Oh, God, this could go really bad.’ You know – he called me to play on his record, and he is who he is, and I’m telling him that I can’t remember playing with him on a Number 1 record. But he thought it was hysterical. It became kind of a joke during the recordings.”

Do you recall which guitars you used on Double Fantasy?

“I used my ’65 SG Junior a lot. I had a black early ’70s Les Paul Special. Those were the two main ones. There was a Strat on a few of those things, as well as my ’68 Gibson J-45.”

Did John have firm thoughts on guitar sounds or parts? Would he direct you at all?

“None of that came up at first. John didn’t lay out anything like, ‘OK, guys, maybe you should go for this sound or that sound.’ We would learn the songs – me, John and the other guitar player, Hugh McCracken – and as we went, John would say, ‘Slick, why don’t you go a little dirtier?’ Then he’d say to Huey, ‘Why don’t you try this?’ But that would happen as the tracks were being run down.”

Every day John would break into some ’50s or ’60s thing – Eddie Cochran or Buddy Holly. We’d all join in for a while, and then he’d say, ‘OK, back to work’

This was after a period when John sort of retired for five years. Was he a little rusty on the guitar, or did he have all his skills together?

“All of his guitar chops were there. His vocal chops were there. He was right on the money.”

As you and Hugh worked things out, did you do any jamming with John?

“Absolutely – and it was a gas. Every day John would break into some Fifties or Sixties thing – Eddie Cochran or Buddy Holly. We’d all join in for a while, and then he’d say, ‘OK, back to work.’ Once in a while, Hugh and I would start playing a Beatles song, and John would go, ‘Cut that shit out!’ It was really funny.”

Which Beatles songs would you play?

“There were a few things. One that would really get to him was She’s a Woman, which isn’t a Lennon song. It’s a McCartney song.”

In his last interviews, John said he planned to tour. Did he talk to you about being in the band?

“Oh yeah, it was all set. He started to talk about it during the last couple of weeks of recording, and in the final week he went to everybody individually and asked if we wanted to do it. The obvious answer was yes. [Laughs] At the time, I had just signed to Columbia, and I was supposed to start a record in February of ’81.

“At that point, John had a plan to do Double Fantasy and Milk and Honey at the same time, but then the plan changed to put out Double Fantasy first, and then we’d finish Milk and Honey and go out on tour.

“I explained my situation to John, that I had a record deal and all that. He got in touch with my management, and they worked everything out with Columbia, who were actually thrilled I’d be going out with Lennon before my record. Sadly, none of that happened.”

Soon after, you were working with Yoko again on Season of Glass with Phil Spector producing.

“Yeah, for the first two weeks. Thank God she got rid of him. It was a nightmare. I mean, he was crazy.”

I’ll do my best deadpan: No, really?

“Yeah. [Laughs] It was the same band from Double Fantasy, but [producer] Jack Douglas wasn’t there. When Yoko said Phil was doing the record, I thought, ‘I’ve worked with a lot of the best producers, and it will be great to work with Phil Spector.’ Well, my tune changed within the first 24 hours of being in a studio with him. He was a fucking nut.”

Phil Spector had a bodyguard the size of the Empire State Building with him, and he was carrying one of those long barrel Clint Eastwood .44 Magnums in a shoulder holster

Did he bring guns to the studio?

“Oh yeah. He had a bodyguard the size of the Empire State Building with him, and he was carrying one of those long barrel Clint Eastwood .44 Magnums in a shoulder holster. I’m going, ‘Dude, this woman’s husband was just killed, and you’re walking around with a gun.’

“The sessions were torturous. I got in the elevator one day with Yoko, and I said, ‘What time is Phil coming in?’ She goes, ‘He’s not going to be here today.’ I asked when he was coming back, and she said, ‘He’s not.’ That was the entire conversation.”

Moving forward, after a while apart, you were pulled back into Bowie’s orbit. Was there a pattern in how and when he called you for various albums and tours?

“I had to learn how David’s mind works. Whatever hit him at a particular time, that’s what he did. I had to go with the flow. I remember I played with him in 2000 – we did Glastonbury and a gig at the BBC Theatre. There were some gigs in New York.

“A while later, he was talking about touring on the Heathen record. So this is weird – I got a call from Mark Plati, and he said, ‘Before you hear this from somebody else, it looks like David’s got another guitar player, so you won’t be going on the tour.’ I just went, ‘Well, another day with David.’

“I was in New York for the week, so I emailed David and asked if he wanted to have coffee. We were supposed to meet, but then his assistant called and said he wasn’t feeling well, and then she asked me to lunch. I went to meet her, and then we went to Looking Glass Studios, where David was doing some vocals. He wasn’t well; he had a cold or the flu. I said hi and was there for a bit, and finally he said, ‘By the way, what are you doing in April?’ I just laughed and said, ‘Why, what’s going on?’ He said, ‘We’re going out.’ I said, ‘Great.’ That’s just the way it went.”

You’re on a couple of other songs on The Next Day – Dirty Boys and (You Will) Set the World on Fire. How did David arrive at which songs he wanted you to play on?

“On that album, unbeknownst to me, David had been in the studio on and off for a year. I was in touch with the guys playing on it, but nobody could say a word because they signed NDAs. So I’m in Montclair, New Jersey, doing a blues gig. I was with a surgeon friend and he had a Cobra car. He said, ‘Hey, let’s drive the Cobra to the gig.’ Sounded good to me… On the way there, the engine caught fire and the car blew up.”

Nice.

“We’re in this high-end neighborhood, and there’s this car in the middle of the street engulfed in flames. The police and news people came down. Somebody spotted me, and it hit the internet. David saw this and he sent me an email – ‘Are you OK?’ I wrote him back and said I was fine. A couple hours later, I got another email – ‘So how have you been?’ ‘Good, how are you doing?’

“We started doing these weird emails throughout the day, and finally I said, 'Are you going somewhere with this?' He goes, 'I’m in the studio making a record, and you need to play on it.' When I got to the studio, I said to him, ‘Did I have to blow up a fucking car?’ [Laughs] You can’t make this shit up.”

Were you surprised when he didn’t call you for Blackstar?

“No. The thing with Blackstar was, none of us knew he was ill. We knew he was ill when the announcement came that he was dead. I spoke to him on the phone the October before he died. I had to ask him some questions because I was doing that Station to Station tour in the U.K. and Japan with Bernard Fowler.

“We had a conversation, but he didn’t mention Blackstar. None of us from the band are on that record, and I can see why. It’s a different kettle of fish from what we would’ve done; it’s kind of an odd jazz thing going on. With David, people were always coming in and out.”

The thing with Blackstar was, none of us knew he was ill. We knew he was ill when the announcement came that he was dead

Another guitarist David worked with quite extensively was Reeves Gabrels. You two never played together with David, though, right?

“Not with David, but Reeves did work on my last solo record. We met around 2010 or so, and we discovered we had more than David in common. When I was just starting out, my bands would play in Staten Island, and Reeves would come to watch me. I had no idea about that until we met.”

You two have jammed together?

“Oh, yeah. A while ago, I was in England working with Glen Matlock, and Reeves was around. We had him come in and sit in with us. As weird as he can play, he can play anything. He’s fantastic.”

You turned down joining Whitesnake because you knew it wouldn’t be a good fit, but have you ever accepted a gig and regretted it?

“There has been that. There have been times when things were slow, and something would come up and I’d do it. But I try to suss that out beforehand so I don’t wind up in something that doesn’t work.”

What kinds of guitars are you playing these days? I assume it’s a lot of your signature guitars…

“Slick Guitars – we’ve got a new batch coming soon. We had one last year [the SL56] with f-holes. It’s really lightweight. The pickups kick ass. They’re made by GFS, but they’re Slick brand pickups. The Tele-style pickups are like old-school Tele models. I play Nash guitars a lot, and I’ve been playing Teles again.

“I’m back to Fender amps. For the last 10 years, I’ve been playing Teles. A few years ago I went out and used Supros. Then when I got home, I plugged into a Bassman and a Marshall Plexi, and I went, ‘A Telecaster with these amps – that’s the shit.’”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.