“There was a lot of dissent from the workforce – there was a mindset of Epiphone not being as important or as easy to work on as Gibson”: The history of Epiphone and Gibson’s rollercoaster relationship – and what’s next for the brands

Gibson’s VP of product Mat Koehler on the enduring partnership between two of the biggest brands in guitar, and how the influence has been in both directions through their shared history

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Epiphone has had a pretty rollercoaster existence. In the early 20th century it was a serious rival to Gibson. By the ’60s it belonged to Gibson. Under Gibson ownership, it was an exclusive high-end brand at first, then became synonymous with affordable instruments.

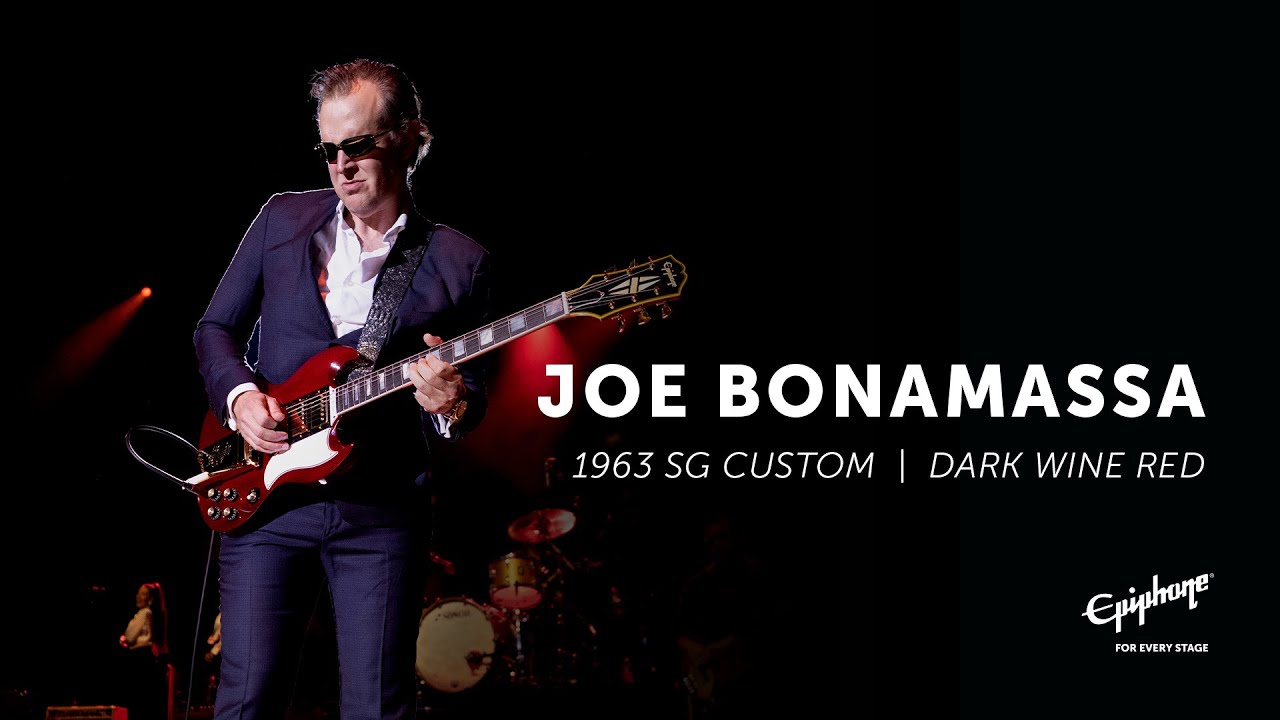

Now, having been revamped once again by Gibson, it’s no longer a poor relation, acquiring its own Custom Shop and a slew of US and overseas-built models that exude a fresh confidence and quality. We ask Mat Koehler, a devoted historian of the two brands, who the heck Epiphone thinks it is…

In the decades before Gibson acquired Epiphone in 1957, how did the two brands stand in relation to one another?

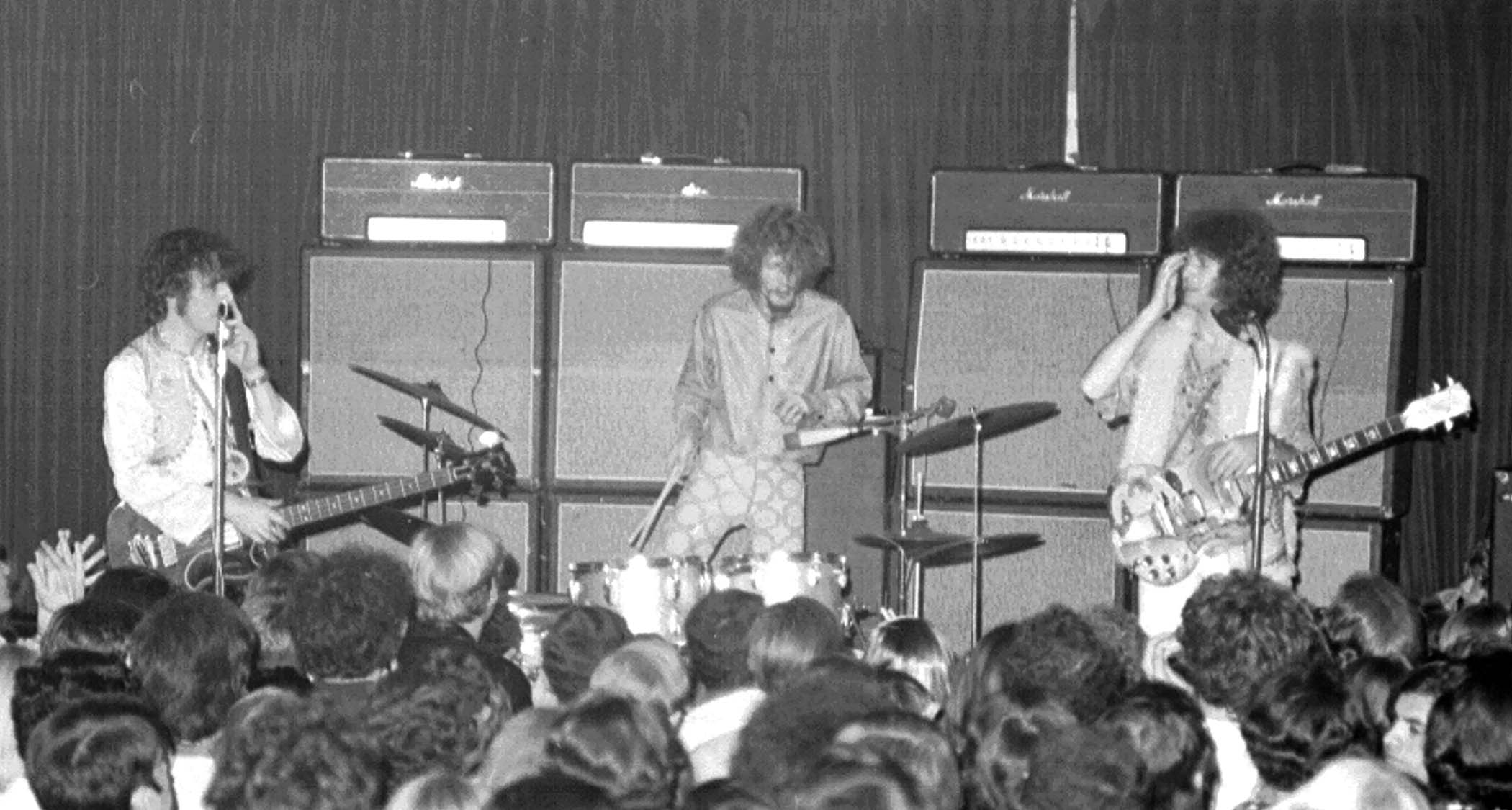

“Gibson was very aware of Epiphone, especially because Epiphone was very much in competition for the bluegrass market with their banjos. Mandolins, too, to some degree, but Gibson was far and away the leader there and had the most premium mandolin options. But going into the big band era, the Jazz Age, Epiphone really became the artists’ preference for archtops, which is ironic because Gibson kind of invented the archtop!

What Epiphone did really, really well was artist outreach: finding new artists, influential artists, and then getting Epiphone models into their hands

“But what Epiphone did really, really well was artist outreach: finding new artists, influential artists, and then getting Epiphone models into their hands. Some of these artists were playing Gibson previously, and some of these artists continued to play Gibson – but they appeared in Epiphone ads.

“So whatever the case, it must have driven the folks at Gibson nuts at the time. And I will say that, having owned many Epiphone archtops from the ’30s, they are outstanding. I mean, they’re really hard to beat, even though Gibson archtops are fantastic from that era as well.”

When Gibson made an offer for Epiphone’s upright bass business, it unexpectedly got the guitar business into the bargain. How did Gibson rationalise owning two guitar brands with such overlap?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Ward Arbanas was the de facto leader of the Epiphone group, and Ward continued to work at Gibson into the ’90s. He ran the parts cage and worked with people that I work with today, which is pretty cool. Ward directed the portfolio for Epiphone, and in February 1958 had basically presented the final portfolio with prices. And this includes flat-top acoustics.

“I think it was 30-some instruments in all. So the strategy with all these instruments was to use up some of the Epiphone parts that they had inherited. Basically, there would need to be very little investment in the material cost. They would also be able to sell Epiphones to dealers that Gibson was not present in because of proximity or other reasons.

“So it was this entire other brand that Gibson – or its parent company, CMI, effectively – could use to sell [additional] products and into dealers. For example, if there was a Gibson dealer in Indianapolis and there was another guitar dealer a block away, you couldn’t sell a Gibson in both shops, but now they had an option to sell Epiphone in one of the shops [and Gibson in the other]. So that’s how they grew the brand.“

How did Gibson tackle the problem of making Epiphone guitars stand out in those early years?

“Epiphone piggybacked off of Gibson in some ways, but then pioneered other new things. For example, Epiphone was developing the double-cut design even before Gibson got into the double-cut Les Paul Specials, so the Coronet and Crestwood actually debuted slightly before the double-cut Les Pauls.

“Then, in terms of price points, Epiphone tended to sit a little higher than Gibson, so it was positioned more like a boutique offering. I think there was some concern that if they positioned Epiphone below Gibson then they were just competing against themselves. They purposely tried to position it just above in order to limit the volume [of orders for Epiphone guitars] since they were being handmade at the factory.”

It’s been reported that the best craftspeople at Kalamazoo were put on the Epiphone production line. Was there any rivalry, internally, between Gibson and Epiphone workers?

“I don’t think there was brand competition, but I can tell you that there was a lot of dissent from the workforce, trying to understand why they were working on these Epiphone guitars as well. I think it was just perceived as, ‘We’re having to take on additional complexity. We don’t understand what’s in it for us here.’ And so Ted McCarty actually sends out a letter to all of the supervisors in the whole factory.

“He says it was absolutely imperative that everyone’s co-operation be given to [cultivating] the success of Epiphone guitars, paraphrasing it. It was clearly not a nice letter, it was basically like, ‘You guys need to shape up or ship out because we need to ensure the success of the brand.’

“So that is very telling – clearly there was kind of a mindset of Epiphone not being as important or maybe even just not as easy to work on as Gibson. Because some of the Epiphone models were more complex. For example, the Sheraton model has a lot more unique features than a 355 and it was priced above the Gibson 355.

“Likewise, the soft round-over on the [edges of] Epiphone solidbodies was kind of unique and unlike anything else Gibson was doing at that time. So just putting my factory hat on, I can see why there were kind of bad feelings about Epiphone at the time.”

Explain how the Epiphone electric guitars differed from their Gibson counterparts…

“The Casino and the 330 were identical to all intents and purposes, so the major changes there are the finish options and the specific type of trapeze. But functionally and playing-wise, they’re the exact same instrument.

“Even material-wise… same construction and everything. The headstock shape was obviously different on the Casino and that changes along with the rest of Epiphone in the early ’60s. But the 355 and the Sheraton really were two different animals completely.

The Sheraton, I think, was supposed to be a continuation of the super-ornate guitars from the golden era of Epiphone archtops, the 30s and 40s

“Firstly, the 355 had an ebony ’board whereas the Sheraton had a rosewood ’board, with lots more multi-ply binding and then additional fingerboard inlay detail on the Sheraton… So I think, just visually, with that beautiful vine headstock inlay as well, the Sheraton really looks like a million bucks – though the 355 is really close behind it – and the Sheraton was priced higher than the 355.

“The Sheraton, I think, was supposed to be a continuation of the super-ornate guitars from the golden era of Epiphone archtops, the ’30s and ’40s. I think that sums it up other than the fact the pickups are different as well in the Sheraton, which started with New York pickups and then went to mini-humbuckers. Whereas the 335 had full-size humbuckers.

“Meanwhile, the Riviera is one of the more versatile ES [guitars] that Kalamazoo ever made. Even when we make them today, they’re in the spirit of those Kalamazoo designs; we’ve made them in the USA previously, and we probably will again, but they have their own thing going on.

So it’s the same construction as the 335, but those mini-humbuckers and that Frequensator tailpiece get a sound. Otis Rush is my go-to for that classic Riviera sound, where it’s just this haunting vocal, very sustaining tone, and that Frequensator tailpiece almost creates this built-in reverb… I can’t even really describe it, but it gets a different hollowbody sound.

“Rivieras have been – and continue to be – very successful. But I still think that they may be a little underappreciated in terms of people not quite understanding what the difference is between a 335 and a Riviera.”

The most obvious differentiator between Gibson and Epiphone, over the years, has been the headstock design. But that itself has changed over the years. Tell us about the evolution of Epiphone’s headstocks.

“Really, the major changes are that you go from the shorter headstock – which we call the ‘Kalamazoo headstock’ because it’s the one that started in New York and then continued into Kalamazoo – and then when Gibson was changing and going to unique parts [for Epiphone guitars, after legacy parts ran out] that were made in-house, they elongated the headstock to give it even more of a distinct look compared with Gibson.

Otis Rush’s Riviera, which had the long headstock, apparently didn’t fit in a Gibson case, so he shaved the top off of the headstock

“It’s a beautiful headstock shape as well, but it’s longer, so I think it probably did pose a few problems with cases and whatnot. Otis Rush’s Riviera, which had the long headstock, apparently didn’t fit in a Gibson case, so he shaved the top off of the headstock.

“So that long headstock then kind of regressed back into the shorter headstock shape – maybe just because of case-fit issues – when Epiphone entered the Japanese-production era. Now, in the modern era, we’re still using a combination of the Kalamazoo short-headstock and then the longer mid-’60s style headstock.”

The Epiphone range is really broad these days and seems split into contemporary guitars with a Gibson influence on one hand, and on the other hand authentic Epiphone designs from the past. How does that work?

“We’ve got the ‘Inspired By Gibson’ Epiphone logo, and then we’ve got the original Epiphone logo, so we’re almost splitting Epiphone into two brands: [one is built around] Gibson-derived products, and the other is built around original Epiphone designs that were under the Epiphone brand originally.

“We’d actually like to take Epiphone Original into new territories of originality – guitars that are either inspired by Epiphones of the past, partially inspired by current Gibsons, or just new. That’s an opportunity that we have not fully explored yet. But we kind of have permission to play here because we can [legitimately] call it an Epiphone Original design because that’s exactly what it will be when it comes out. So it really gives us a lot of flexibility.

“Also, we now have an ‘Inspired By Gibson’ Custom Shop range – the Korina guitars [such as the recent Explorer and Flying V reissues] are an example of that, where we’re trying to hold nothing back and working closely with the [Gibson] Custom Shop team.

“I mean, we all work together, but we’re not siloed at all. We all work here at HQ, next to each other, so we’re all in this together and we’re trying to do things like use what we learned while [3D] scanning a vintage Explorer [for the Gibson Custom Shop] and putting that work into new Epiphone models, which is really cool.”

Are there any unsung or misunderstood models from Epiphone’s past that deserve better recognition, do you think?

“On the acoustic side, one of the more beautiful designs ever to come out of Kalamazoo was the Excellente acoustic, just super, super cool, which was clearly positioned as the pinnacle flat-top that Gibson made, with Brazilian rosewood, back and sides, beautiful eagle inlay on the pickguard and lots of mother-of-pearl, and they only made I think 120, maybe 140 maximum in the ’60s.

The Texan, which continues to be very popular because of Paul McCartney, is pretty different from the J-45. I think this is one of the biggest misconceptions there is about an Epiphone guitar

“Our reissue today is arguably better than those and it comes in at a thousand bucks, whereas even if you can find an original Excellente, you’re looking at five figures. The ones we make today are really top-notch, and I’d put them up against anything. I own one, I play one. So that’s definitely a personal favourite of mine.

“It’s also worth noting that the Texan, which continues to be very popular because of Paul McCartney, is pretty different from the J-45. I think this is one of the biggest misconceptions there is about an Epiphone guitar: people assume the Texan is Epiphone’s version of a J-45.

“But it’s long-scale, so it’s a completely different animal. It really has its own vocality, has its own kind of sustain and how the notes ping… so the scale length difference on the Texan really sets it apart. I own a Texan as well, so I’m practising what I preach here [laughs].”

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.