“Epiphone will always be Gibson’s older brother, and its history is perhaps the most interesting of any guitar brand”: Celebrating 150 years of Epiphone – from luxury archtop maker to budget builder and rock icon

As Epiphone commemorates a century-and-a-half in business, we enlist the help of vintage guitar experts and Gibson’s own archivists to tell its remarkable history

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

You’ll know Epiphone today as Gibson’s alter ego, with its line of well-priced alternatives to the senior brand, as well as reincarnations of some of its own historic models such as the Casino, Texan and Coronet. Epiphone’s roots, though, go back further than you might think – all the way to Turkey in the 1890s, in fact, when Anastasios Stathopoulos began making lutes, violins and other instruments.

Anastasios emigrated with his family to the United States in 1903, in the process losing the final ‘s’ of their surname, and he set up in business in New York City, successfully making mandolins, which were in vogue at the time, and also banjos, much favoured by early jazz players in the city and beyond.

When Anastasios died in the mid-1910s, his son Epaminondas began to run the business. He was known as Epi, and at first he renamed the firm as House Of Stathopoulo, introducing the Epiphone brand in 1924 and bringing in his brothers Orphie and Frixo.

Again following instrumental fashion, as the guitar began to make its voice heard, Epi added the Recording line of carved-top and flat-top acoustics in 1928, some with a distinctive curved cutaway. In the same year, Epi again renamed the business, this time as the Epiphone Banjo Company.

In 1931, along came Epiphone’s Masterbilt archtops: De Luxe, Broadway, Triumph, Royal and Zenith, plus a few years later the Tudor, Spartan and Regent. They competed directly with the market leader, Gibson, and in many ways were superior.

The Masterbilts marked the start of a battle for leadership in the acoustic archtop market between the two American brands, with bigger sizes and bigger claims throughout the 1930s and into the ’40s for models such as Gibson’s Super 400 and Epi’s Emperor.

Epiphone introduced electric guitars late in 1935, at first with the Electar brand, and the following year added its new F.T. flat-tops. Epi hired Herb Sunshine to develop the new-fangled electric instruments, and Herb in turn hired Nat Daniel, later of Danelectro fame, to create the necessary amplifiers.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As America entered World War II in 1942, Epiphone was neck and neck with Gibson as the biggest name in American guitars

Sunshine designed a new pickup for Epiphone/Electar that was the first with screw polepieces, allowing height adjustment for individual string volume, and also Epiphone’s distinctive twin-armed Frequensator tailpiece. Alongside Epi’s late-’30s electric instruments was the Rocco Tonexpressor volume and tone foot controller, the first ever guitar pedal.

As America entered World War II in 1942, Epiphone was neck and neck with Gibson as the biggest name in American guitars. By now, Epiphone boasted a packed catalogue with nine acoustic archtops, from the mighty Emperor to the small-body Olympic, four F.T.-series flat‑tops, two classical models, four electric archtops (Zephyr De Luxe, Zephyr, Century and Coronet), plus electric steels, acoustic and electric mandolins, upright basses, acoustic and electric banjos, amplifiers and accessories.

In 1943, Epi Stathopoulo died at the age of just 49 and his brother Orphie took over the company. It had trouble regaining ground after the war ended in ’45, despite a reasonably strong reputation – and an impressive new high-end electric archtop, the Zephyr Emperor Vari Tone.

Introduced in 1950, it boasted three ‘New York’ pickups and six push-button selectors, and was soon renamed the Zephyr Emperor Regent (and later simply the Zephyr Electric).

Following a strike in 1951 at its factory in New York City, Epiphone relocated to Philadelphia. Many of the discontented workers departed and helped to create the Guild company in New York. Epiphone’s last new instrument of the era was introduced in 1955 – a budget signature electric archtop for the jazz guitarist Harry Volpe. It seemed like time was now running out for Epiphone. But waiting in the wings was the brand’s old rival, Gibson.

Rival turned owner

Bosses at Gibson had seen their upright-bass manufacturing disappear following World War II – and they couldn’t help but notice the problems over at Epiphone. In the early ’90s, this writer spoke to Ted McCarty, Gibson’s boss of this era, and he remembered how those problems appeared to present an opportunity. However, it wasn’t the guitars that attracted Gibson; it was Epiphone’s upright basses.

“Our biggest competitor was Epiphone – and I bought Epiphone for Gibson in 1957,” McCarty recalled. “By that time we had overtaken Epiphone, and they were going under. Some people at Gibson wanted us to get back into the bass business. We couldn’t find all of the forms and what-not to make the Gibson bass – they’d been thrown away during the war.

“So I told Orphie Stathopoulo that if he ever decided to sell his bass business, let me know. Later, Orphie called me, saying, ‘Ted, I’ve got to sell out, I need money, and you once said you’d like the bass business. If you still want the bass business, it’s yours.’”

McCarty talked it over with MH Berlin, his boss at CMI, which had owned Gibson since 1944. No doubt Stathopoulo’s asking price of just $20,000 was a significant part of that discussion. McCarty called Stathopoulo, told him it was a deal and said they would come over and collect all the relevant material.

“What we found out,” McCarty continued, “was that we were buying the whole business. Not just the string-bass deal, but because they didn’t know over in Philadelphia, well… they put in all the forms and parts and what-not to make Epiphone guitars.

“We discovered all this when they shipped the whole thing back to us in a big furniture truck. I put Ward Arbanas in charge of it, and we set it all up to make Epiphone guitars.”

McCarty’s intention was to market Gibson and Epiphone separately. He said they knew plenty more stores beyond their core dealers who wanted to sell Gibson. “We wouldn’t sell it to them,” he recalled. “I said to Berlin, ‘Look, now we have a recognised top-quality guitar that was always competitive with Gibson – now we’ve got two good lines to sell.

“We can’t sell this other guy our Gibson, but we can sell him Epiphone, and we’ll make it equal in quality and all the rest.’ And within a few years we were doing about $3 million in Epiphone. Orphie was happy to get the $20,000, and I had made a very fortuitous purchase.”

Gibson’s new Epiphone upright basses didn’t last much more than four years in the catalogue, but the guitars were a different story. Soon, Gibson had positioned Epiphone as an important “new” guitar brand, a brand that would become a valuable asset for Gibson – and a brand that is very much alive today.

A remodelled brand

Gibson launched the revived Epiphone brand at the 1958 NAMM Show and early the following year it began to ship the new instruments from the Kalamazoo factory to a new network of Epiphone stores.

Alongside the relevant Gibson models of the day, there were 15 Epiphone archtop and flat-top acoustics, and hollowbody and solidbody electrics. Gibson cleverly decided not to simply extend the life of the existing Epiphone models but to adapt and create what amounted to a new line of models, many of which sat between Gibson’s various models, rather than competing directly with them. The impression was that Epiphone guitars had a new identity. And as a bonus they were built in the same factory as Gibson and to the same standards.

Most of the differences between comparable Gibson guitars and the Epiphone models introduced in 1959 were down to distinctive Epi features. Pickups, for example, were at first the ‘New York’ single coils, as well as some P-90s and Melody Makers, and a little later mini-humbucker pickups.

There was some specific Epiphone hardware, too, notably that Frequensator tailpiece, plus a new Tremotone vibrato, as well as individual decorative touches, not least the fancy inlay on some of Epiphone’s fingerboards and headstocks.

Epi’s new offering of four hollowbody electric guitars each came in Gibson’s thinline body style. The single-cut Emperor was, as ever, top of the tree, still with the old model’s three pickups but replacing the funky button selectors with a conventional three-way. There was no obvious model in Gibson’s contemporary lines to compare to the Emperor.

The double-cut Sheraton was another impressive beast, with its centre-block body making it the only semi-solid in the new line, sitting somewhere between Gibson’s ES-335 and 355. Two more models completed the hollowbody electrics for now: the two-pickup single-cut Zephyr and the non-cutaway single-pickup Century, again with no evident Gibson equivalents. There was also an electric with a full-depth hollow body, the two-pickup single-cut Broadway.

Two new solidbody electrics opened up a category without precedent for Epiphone, a field where Gibson had some seven years of experience. The two-pickup Crestwood Custom and single-pickup Coronet were made in Gibson’s regular set-neck style, their double-cut slab bodies finished in cherry red.

There was a perceptible hint of Les Paul Specials and Juniors about the Crestwood and Coronet, but despite their popularity, the Epiphones of this period never rivalled the sales punch of Gibsons. For example, the Coronet and Les Paul Junior listed at the same price, $132, but the factory shipped 237 Coronets in 1959 and 221 the following year, while Gibson’s equivalent Junior shipped 4,364 in 1959 and 2,513 in 1960.

The new-style Epiphone brand launched four flat-tops, headed by the Frontier, intended to compete with Martin’s square-shouldered Dreadnoughts. It was joined by the round-shouldered Texan (calling to mind Gibson’s jumbo J-45 and J-50), the smaller Cortez (like Gibson’s LG-2), and the Cabellero (like an LG-0).

It wouldn’t be Epiphone without archtop acoustics, and the four models that went on sale in 1959 ranged from the lofty Emperor (comparable to Gibson’s Super 400), through two more single-cuts, the Deluxe (L-5C) and the Triumph (L-7C), and on to the non-cut Zenith (L-50).

Into the ’60s

Gibson’s apparent success with its transformation of the Epiphone brand meant that as the ’60s rolled into view, more models were added to the lines. The range of acoustic flat-tops was widened considerably as the folk boom resonated around the guitar world. There were a few nylon-string classicals, with the Seville model offered in an Electric version with a pickup.

The steel-string line expanded in 1963 to include the Excellente, El Dorado and Troubadour, followed by the small-body Folkster (1966) and a couple of 12-strings, the Bard and Serenader (1962 and ’63). But the main action was with Epi’s electrics, and the thinlines proliferated. The Sorrento, with single pointed cutaway and two mini-humbuckers, was introduced in 1960, while the non-cutaway Granada (1962) had a Melody Maker pickup, with a single-cut version added three years later.

Epiphone’s Casino (1961), offered at first with single as well as double P-90s, was similar to the double-cut hollow style of Gibson’s ES-330, while the Riviera (’62), with two mini-humbuckers, was more like a 335, with the internal body block. A 12-string Riviera was added in ’65.

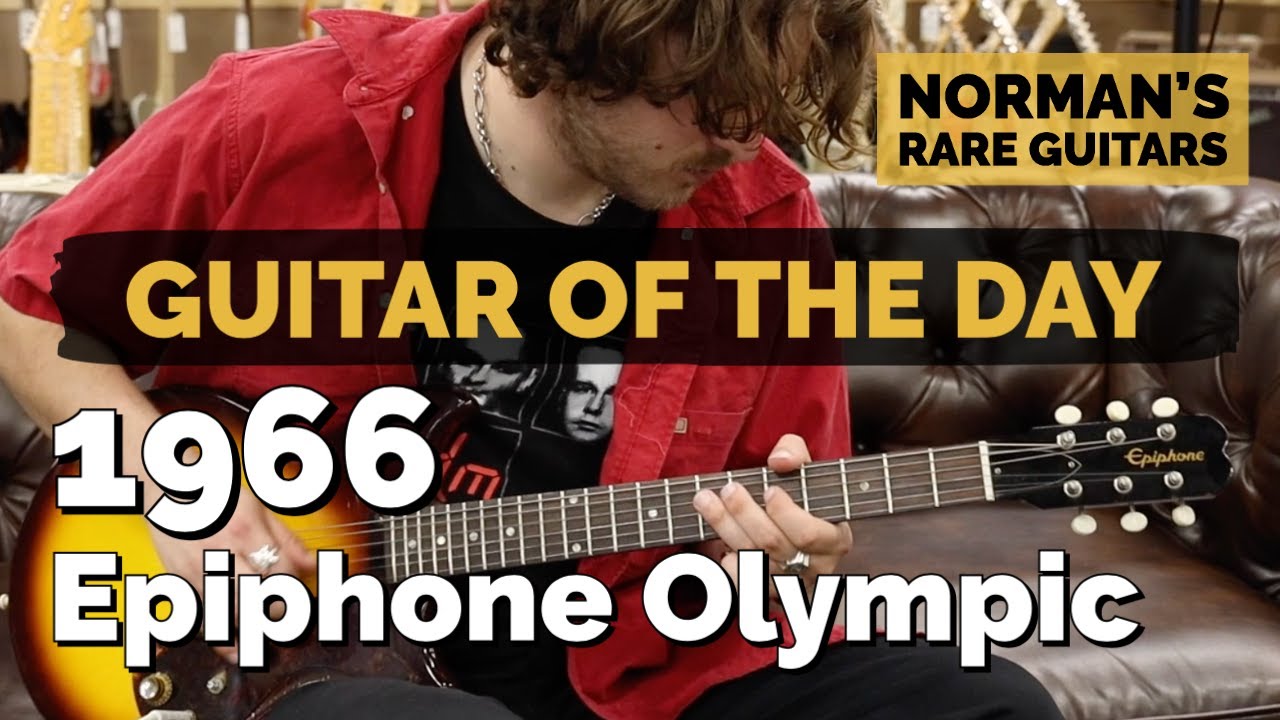

More solidbody electrics began to fill Gibson’s Epiphone lines. The Wilshire was like a Coronet fitted with two P-90s and suitable controls. It boasted the modified new-for-1960 body seen on all three solidbody models – Crestwood Custom, Wilshire, and Coronet – with rounded body edges as opposed to the original square-edge style. Also that year, Epi launched a budget solidbody, the Olympic, in short-scale form with one pickup or full-scale with one or two.

In 1963, Epiphone again revised its solids, the asymmetrical body thinner and with a long upper horn and short lower horn, plus a cheekily Fender-like “batwing” shape headstock with tuners on one side. The high-end three-pickup Crestwood Deluxe also joined the line in ’63, and three years later a Wilshire 12-string was added.

Gibson tested some new ideas in ’62, safely away from the main brand, with the multiple-control Professional. There were two companion amps: the 35-watt EA8P with 15-inch speaker, or the 15-watt 12-inch EA7P. Each had just a single knob, but its main controls – seven switches and five knobs – were on the guitar itself. It was a short‑lived experiment.

Epiphone introduced a couple of signature models, at first in ’63 with the Caiola (later the Caiola Custom), for New York session guitarist Al Caiola. It was a sort of long-scale Sheraton with five tone switches on a curved control panel. A less fancy Caiola Standard, with P-90s, was added three years later.

Then in ’64 came the Howard Roberts Standard, named for another top session player. Similar to Gibson’s sharp-cutaway L-4CES, it added a long scale, oval soundhole and a floating mini-humbucker. The fancier Howard Roberts Custom followed in ’65.

The Beatles effect

By the mid-’60s, almost a fifth of guitar shipments from Gibson’s factory were Epiphones. And it was around this time that The Beatles picked up a few. Paul began the trend during his band’s second US tour, in 1964, when he bought a Texan flat-top.

It became a favourite recording and songwriting tool, but he also used it occasionally for TV performances of Yesterday. Later that year, he bought a ’62 Casino with Bigsby tailpiece, restrung and flipped to accommodate his left‑handed style.

In 1965, John and George each bought a new Casino, using them on the sessions for Revolver, as did Paul

In 1965, John and George each bought a new Casino, using them on the sessions for Revolver, as did Paul. George’s came with a Bigsby, John’s with the regular trapeze tailpiece, and the pair played them throughout the band’s final live dates from June into August ’66 in Germany, Japan, The Philippines and the USA. This appears to have had a tangible effect on the model’s sales figures at that time.

The year before John and George’s Epis were seen on those live dates, Gibson shipped 853 Casinos from the Kalamazoo factory. In ’66, the year of those final Beatle tours, the number doubled, to 1,655 shipped, and for ’67, the total nudged higher still, to 1,814. Impressive increases – but not necessarily thanks to the Beatles effect. In fact, guitar sales for all makers generally peaked and then fell around this time.

Following our example of the Casino, in 1968 its annual sales slumped to 468, dramatically down from that 1,800 of ’67. In total, Gibson shipped a touch over 4,000 Epiphones in ’68, a paltry 20 per cent or so of the peak a few years earlier – and the output continued to plummet in ’69.

Gibson had its own business problem, and its president, Ted McCarty, who had steered the firm through its glory years, left in 1966. Gibson-brand sales dropped substantially in this period, but it was strong enough to weather the storm. Epiphone, however, was now in serious trouble – one indication was an absence of any new models since ’66.

By the end of the decade, Gibson’s parent company, CMI, was taken over by ECL, an Ecuadorian brewing firm, and the result was a new owner, Norlin. Amid these trying times, the decision was made to switch Epiphone production to Japan.

Made in Japan

A new, reduced line of Epiphones was made in Japan by Matsumoku, and by 1971 the catalogue offered just five Martin-like flat-tops, three classicals and a Fender-like solidbody plus similar bass.

The only guitar at all reminiscent of earlier times was the double-cut thinline 5102T (plus matching bass), which on a good day resembled a Casino. Other than that, there was not a hint of the ’60s models that had given new life to Epiphone. Instead, guitarists were presented with what must have seemed like just another bunch of import guitars.

Gradually, the Japanese Epis gained more character, and a couple of Crestwood-like solids, the ET-275 and 278, were described as “original Epiphones”. A little later in the ’70s there were SG copies and some flat-tops that recalled classic Gibson models. New designs began to appear, too, such as the Scroll and Genesis solidbodies and Nova flat-tops. By the end of the decade, however, further changes were in the air.

In the ’80s, Gibson began to shift Epiphone’s identity, at first with the short-lived American series, made once again at Gibson’s Kalamazoo factory, and then, at last, some Japan-made reissues of the ’60s thinline electrics – a Casino, of course, a Riviera and a Sheraton, plus an Emperor, also offered with full-depth body.

Another new start

Norlin collapsed in 1984 amid these promising signs, and a new owner acquired Gibson and Epiphone two years later. Yet again, a new line of Epiphones was devised, this time made at Samick in Korea. Mostly they were Strat-like solidbody variations, but there were also some lookalikes based on a Flying V and an Explorer.

Epiphone USA Casinos are finding new audiences 60 years after The Beatles used them

Mat Koehler

Just as Fender was doing with its new Squier brand at the time, Gibson stressed its relationship with a “Epiphone by Gibson” logo on the headstocks. This clear and obvious link – with Epi versions of famous Gibson designs, often with modern features – is still at the heart of Epiphone’s identity today, with manufacturing now primarily at Epiphone’s own factory in China.

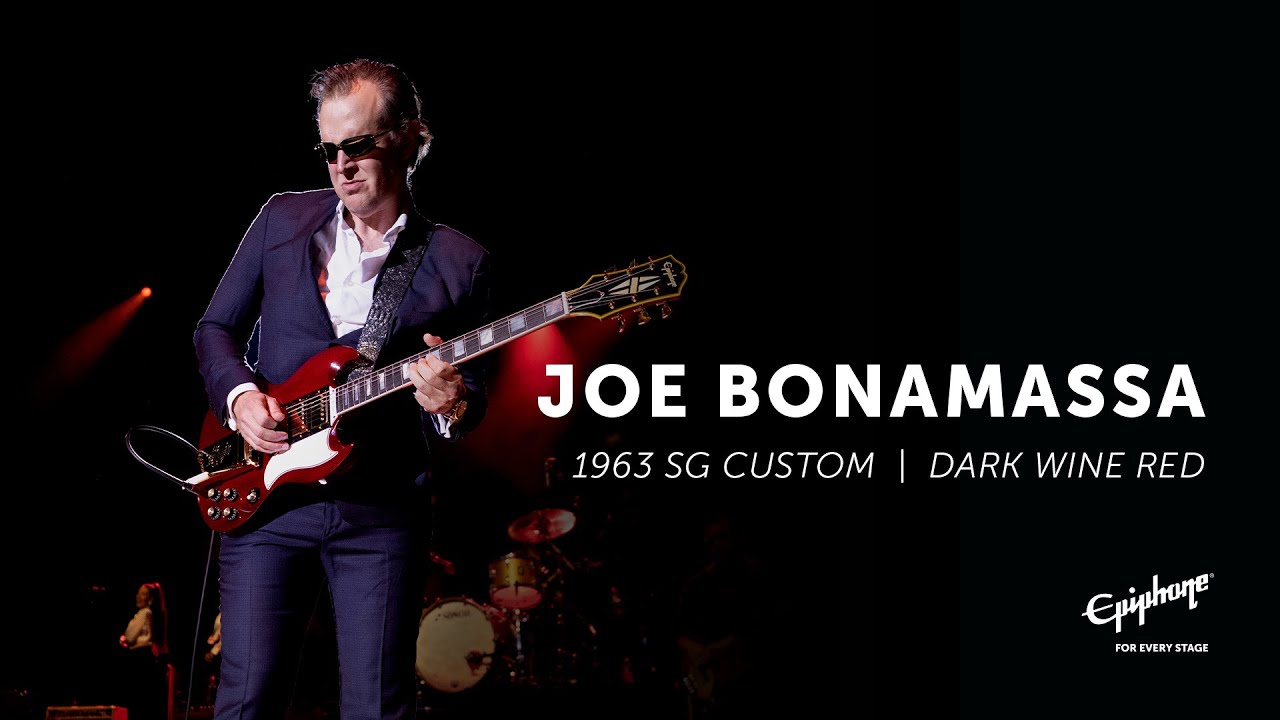

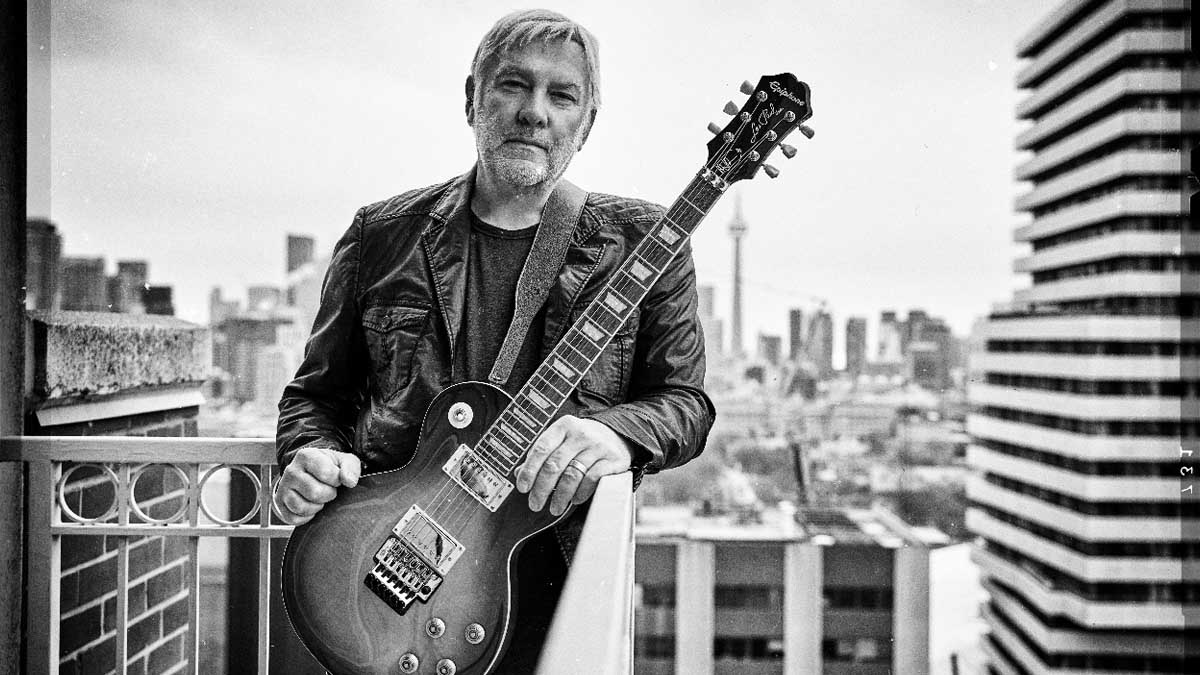

A run of artist models has also strengthened Epi’s modern image, highlighting today’s lines with prestigious models such as Joe Bonamassa’s vintage-flavoured 335 and Alex Lifeson’s Floyd Rose-equipped Les Paul Custom Axcess.

Mat Koehler, vice president of product at Gibson Brands, sums up Epiphone’s important role within today’s Gibson company, revived and sharpened since the newest owners took over in 2018. “Epiphone will always be Gibson’s older brother, and its history is perhaps the most interesting of any guitar brand,” Koehler suggests.

He charts the past achievements – “Epiphone’s sonic dominance in the jazz era, Les Paul constructing his Log at the New York factory, Gibson’s acquisition and resurrection of the brand, and the Japan-made years with some still highly regarded instruments being used by professional musicians” – and then considers Epiphone today. “Epiphone USA Casinos are finding new audiences 60 years after The Beatles used them,” he says, “and the unique Epiphone Prophecy models take the brand into modern music and tastes.”

Epiphone is claiming 2023 as a key birthday in its long history. “We’re celebrating Epiphone’s 150th Anniversary year with a variety of limited-edition models representing the most desirable and collectible historic Epiphone models,” Koehler continues, “both archtop and solidbody, most of which we’ve never made since their original debut.”

It’s been a long, eventful and sometimes difficult history, but it’s hard not to conclude that Epiphone is in better shape today than it’s ever been. Epaminondas Stathopoulo would have been proud.