Gang Of Youths: “While I’ve grown so much musically, I’ve also been coming into my own as an adult”

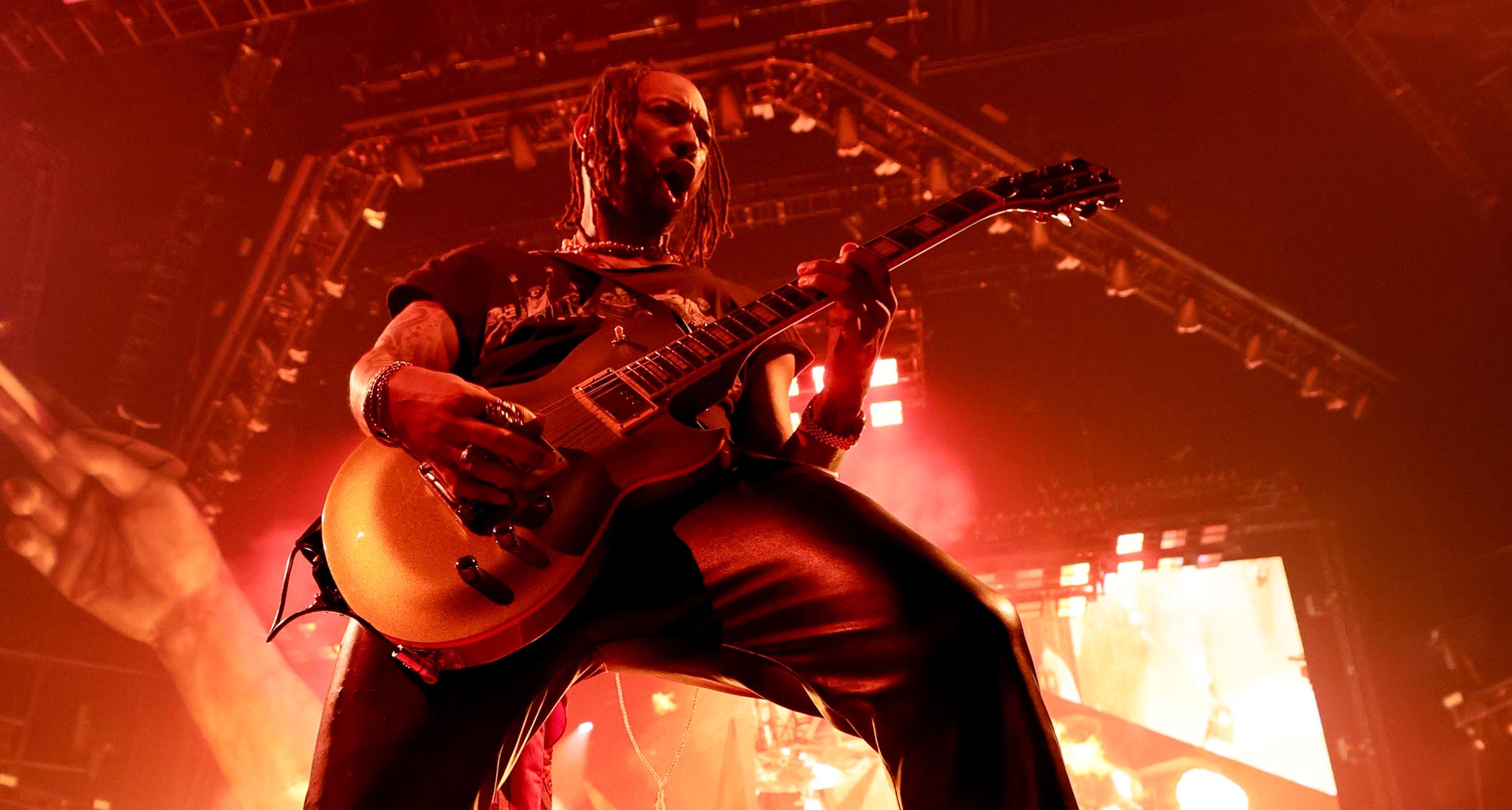

Gang Of Youths’ instrumental mastermind Jung Kim fills us in on the London-via-Sydney band’s landmark third album, Angel In Realtime: an opulent epic, ambitious even for them.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Though grandeur has always been a cornerstone of their sound, Gang Of Youths’ long-awaited third album, Angel In Realtime, takes the Sydney-native, London-based outfit to new heights of sonic opulence. It’s a conceptual epic, following frontman Dave Le’aupepe on a personal journey as learns about his estranged father’s heritage and background – much of which was kept was kept secret – in the wake of his death. As such, it far eschews the dancey indie‑rock slant of the band’s first two records, and dives deep into the well of widescreen theatre-pop they’d only touched on scantly prior.

Part of the musical shift comes down to a change in personnel: the band’s lead guitarist, Joji Malani, left the fold in 2019, leaving Jung Kim – who formerly held down the rhythm section – to step into his role. Tom Hobden filled the subsequent gap left by Kim, but came with more skill as a violinist. Flanked by that and Kim’s kaleidoscopic prowess as a keyboardist, Angel In Realtime sports an expansive and experimental palette, building lush gardens of musicality for Le’aupepe’s reverberant tenor to frolic through.

Australian Guitar caught up with Kim to explore how Gang Of Youths’ new effort pushes the band to exciting new heights, and how they endeavoured to reinvent themselves right in the midst of their mainstream breakthrough.

How did you want this record to reflect Gang Of Youths’ musical evolution over the last five years?

Personally, I think having so much time off – like the rest of the world did – to just sit and ruminate and figure out how to deal with space and time, I’ve come to discover so much new music. Because that’s kind of all we had. I had so much time to figure out all the things that I missed out on, growing up, because I never really had a childhood where my parents would shower me with music – it was very much just classical music in my household. So learning about contemporary music, these past two or three years have been amazing for that. Especially with the beauty of streaming, being able to look up any playlist and discover so many new artists.

Also, to be able to learn so much about the stories that we’re trying to tell on this record, in terms of what Dave experienced in the last couple of years with his cultural heritage. There was a lot to explore with the passing of his father, and a lot of the things that were revealed to him in the aftermath of that. So while I’ve grown so much musically, I’ve also been coming into my own as an adult because of all these universal themes and life experiences that we all eventually, inevitably, have to go through. It’s been really enriching. But of course, I’m glad to be on the other side of what was – I’m sure for everyone – a stressful few years.

The first thing I noticed with this record is that there’s actually not that much guitar on it. How did your relationship with the instrument change on this record?

I think my relationship with the guitar had to mature quite a bit. The way I would describe everyone’s role in the band, in terms of the songwriting and production, is that I wouldn’t say any of us were necessarily glued to a single instrument. I think that’s why there is such a little guitar, in a traditional sense. On Go Farther In Lightness, there were a lot more thrashier kinds of sounds – a lot more distortion and fuzz, and stuff like that – but I think because we’ve already done that, and we’ve also stepped into this new phase of trying to make a record, from the point of view that all of us could kind of pick up any instrument we wanted, it just ended up being a record where there was just not so much guitar.

We were just more interested in playing piano, or playing around with modular synthesisers, or chopping up samples and stuff like that. And that just naturally became our interest, I think, because it’s something we’d never really done before. That was just way more exciting than doing that thrashy wall of sound again. But in terms of when and where guitar was used on this album, I think we had to be more conservative because there’s so much space being occupied. I mean, when every corner and crevice of the musical campus is occupied in some way, you have to be a lot more tensional.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

How meticulous is that process, finding where every element fits? Is part of it just creative serendipity, or do you really slave over the mix?

Yeah, I feel like “slaving away” might be the best way to describe it, to be completely frank. We definitely were slaving away at trying to figure out exactly what fits where, and what felt right. A lot of the time, when we’d play guitar, normally we’d be like, “Whatever, that works I guess,” but this time around we were pretty surgical. I think we had a pretty strong sense of what sounds and textures we wanted to reference; a lot of that lended itself to neoclassical influences, like Steve Reich or Philip Glass – which is obviously not guitar music at all. At some point in the middle – or around the end – of the song ‘Unison’, there’s this sort of meandering, cascading guitar loop in the background, and that is definitely a reference to that minimalist music that we’re trying to incorporate into the record.

There’s a lot more acoustic guitar than electric, too. Did that go hand in hand with the more intimate feel that a lot of these songs are framed around?

For sure. I think mostly because we have so much interest in complexity, coming from all these other instruments that never really featured in our music before. I think the guitar naturally had to fill the space that those things weren’t, which often meant it needed to be really delicate – a lot of the time, I’d just play chords in the background, and just strum away to provide that harmonic sort of bed. And I mean, I’m always so tempted to just create the coolest lick, or feature the coolest sound or whatnot – but I guess that’s just where that creative maturity had to kick in. There’s a level of humility you have to have when you’re dealing with music that’s so dense and complex. It really is “the humble guitar” at this point.

Well going back to that notion of creative growth, this is, of course, the first album with Tom in the mix and Joji out of it. Was that shift in dynamic something you had to adjust to?

Definitely. I mean naturally, I had to take over that role, being more of a guitar player. And although I grew up playing guitar, it was such a weird transition. In the ten-plus years that I’ve been in Gang Of Youths, I’ve always been more in the mindset of a keyboardist and a synthesist, and someone who’s really into production. And so all of a sudden, to put this hat on and try to be a guitar player – but at the same time, be a guitar player that took a bit of a backseat – it was really kind of jarring for me.

And definitely, yeah, I guess it took a long time for me to realise that y’know, although I am technically the guitarist in this band, there’s so much that I think that I can dive into, that could be of use to the band, other than just being someone who can shred

Ellie Robinson is an Australian writer, editor and dog enthusiast with a keen ear for pop-rock and a keen tongue for actual Pop Rocks. Her bylines include music rag staples like NME, BLUNT, Mixdown and, of course, Australian Guitar (where she also serves as Editor-at-Large), but also less expected fare like TV Soap and Snowboarding Australia. Her go-to guitar is a Fender Player Tele, which, controversially, she only picked up after she'd joined the team at Australian Guitar. Before then, Ellie was a keyboardist – thankfully, the AG crew helped her see the light…

- Ellie RobinsonEditor-at-Large, Australian Guitar Magazine