Interview: Meshuggah Discuss Their New Album, 'Koloss'

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It's 7 p.m. on Saturday, May 5, and Sunset Boulevard is filled with the type of scenery native to few places outside of West Hollywood: groups of guys with fancy jeans, designer shoes and artfully mussed hair, and packs of tanned girls in impossibly short skirts, high heels and tiny tops are bouncing from bar to bar, indulging in the Cinco de Mayo festivities.

Guitar World is witnessing this roving party from the outdoor deck of the House of Blues, a several-story, faux-ramshackle building fashioned in the style of old tin-roof blues shacks. We can’t help but laugh at the reactions of the shiny, happy people of L.A. as they attempt to navigate past the growing mass of shaggy, black-clad metal acolytes that are lined up in front of the venue. While the passersby may be on the hunt for tequila and tacos, the concert crowd has come out for some decidedly heavier fare: Meshuggah, Sweden’s leaders of technical groove metal, who are at the House of Blues tonight to perform in support of their newly released seventh album, Koloss.

“Do you know tonight is Cinco de Mayo and the supermoon?” asks Fredrik Thordendal, as he steps out onto the deck. The Meshuggah guitarist has just been informed that, by some twist of astrological fate, the group’s show not only falls on Cinco de Mayo—the hard-partying holiday on which people of all ethnic backgrounds celebrate Mexican culture—but also aligns with a cosmic phenomenon in which the full moon is at its closest point to the Earth, causing it to appear significantly larger and brighter than usual. To Thordendal and his bandmates—co-guitarist Mårten Hagström, vocalist Jens Kidman, bassist Dick Lövgren and drummer Tomas Haake—the synchronism is alarming. Says the guitarist, “It’s gonna be crazy!”

Which is appropriate, given the occasion. When Meshuggah unleash their live musical juggernaut on even the most inauspicious of days, it’s like witnessing an elemental force of nature—a sublime convergence of down-tuned eight-string guitars, relentlessly creative rhythmic propulsion and brilliantly savage energy. Meshuggah’s power and influence within the extreme metal scene is undeniable.Witness the popularity of the metal subgenre known as “djent”: the movement, which includes bands like Periphery and Animals as Leaders, takes its name from the vocal approximation of the sound produced by Thordendal and Hagström’s high-gain, palm-muted guitar work.

So with the stars lining up, a sci-fi–worthy moon floating on the night’s horizon, and Meshuggah poised to deliver a one-and-a-half hour set to a fanatical sold-out crowd, one can only imagine what form of creation, or perhaps chaos, is about to be unleashed. Guitar World has been given exclusive access to this evening’s proceedings to shadow Meshuggah, get the story behind Koloss—their most accessible, grooving album to date—and document what happens when a Swedish metal band and its horde of fans overtake West Hollywood.

The strange scene begins to unfold a few hours earlier at load-in amid a cloud of burning rubber and the arrival of a tow truck that, like the rising moon, is bizarrely oversized.

2 p.m.Load-In

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

When the bus carrying Meshuggah pulls up to the side entrance of the House of Blues, the group finds that the bus belonging to opening band Baroness is stuck on the nearly 30-degree incline and is partially blocking the load-in area.

In an unfortunate miscalculation, Baroness’ driver has pulled too close to a barrier at the end of the incline and is desperately trying to correct the situation by backing up the hill. But because the angle is so steep, the bus can’t gain enough traction to reverse, and with every attempt the vehicle skids closer to colliding with, and most likely destroying, some massive concrete planters. After a few headshakes and eye-rolls, Meshuggah’s techs jump to the task of off-loading road cases filled with racks of guitars, drums and amps, as well as the elaborate stage props and lighting setup, while the band makes its way into the venue. The techs complete the task just as a massive tractor-trailer tow truck—the biggest we’ve ever seen—arrives to extract Baroness’ bus.

We head inside the House of Blues and navigate through its many anterooms until we stumble upon Meshuggah’s third-floor dressing room, where Thordendal and Hagström are settling in. The two guitarists are visions of Nordic pedigree: tall, massive men with strong features and long dark hair. It’s not a jump to imagine we’re meeting a pair of ancient Vikings—just swap out the eight-strings for battle-axes and you’re almost there. The guys might cast an imposing shadow, but within minutes of exchanging hellos, it’s apparent that they are exceedingly accommodating and gracious hosts, and very excited about tonight’s show.

For this evening’s gig, Meshuggah will be delivering an epic set that draws from nearly every stage of technically intoxicating metal in their 25-year career, including Koloss. They’ll also be unveiling their recently reinvigorated live act, which features an over-the-top theatrical light show and larger-than-life presentations of the album’s cerebral, tripped-out artwork.

“We’ve been talking for a while about how we wanted to incorporate a better light show and better scrims with a really good set,” Hagström says as he takes a seat in the dressing room and prepares to film a demo for his new Ibanez M8M guitar. “At this point in our career, we have the catalog for it and we had the time to make some good informed decisions about the presentation. It feels really inspiring to deliver something better.”

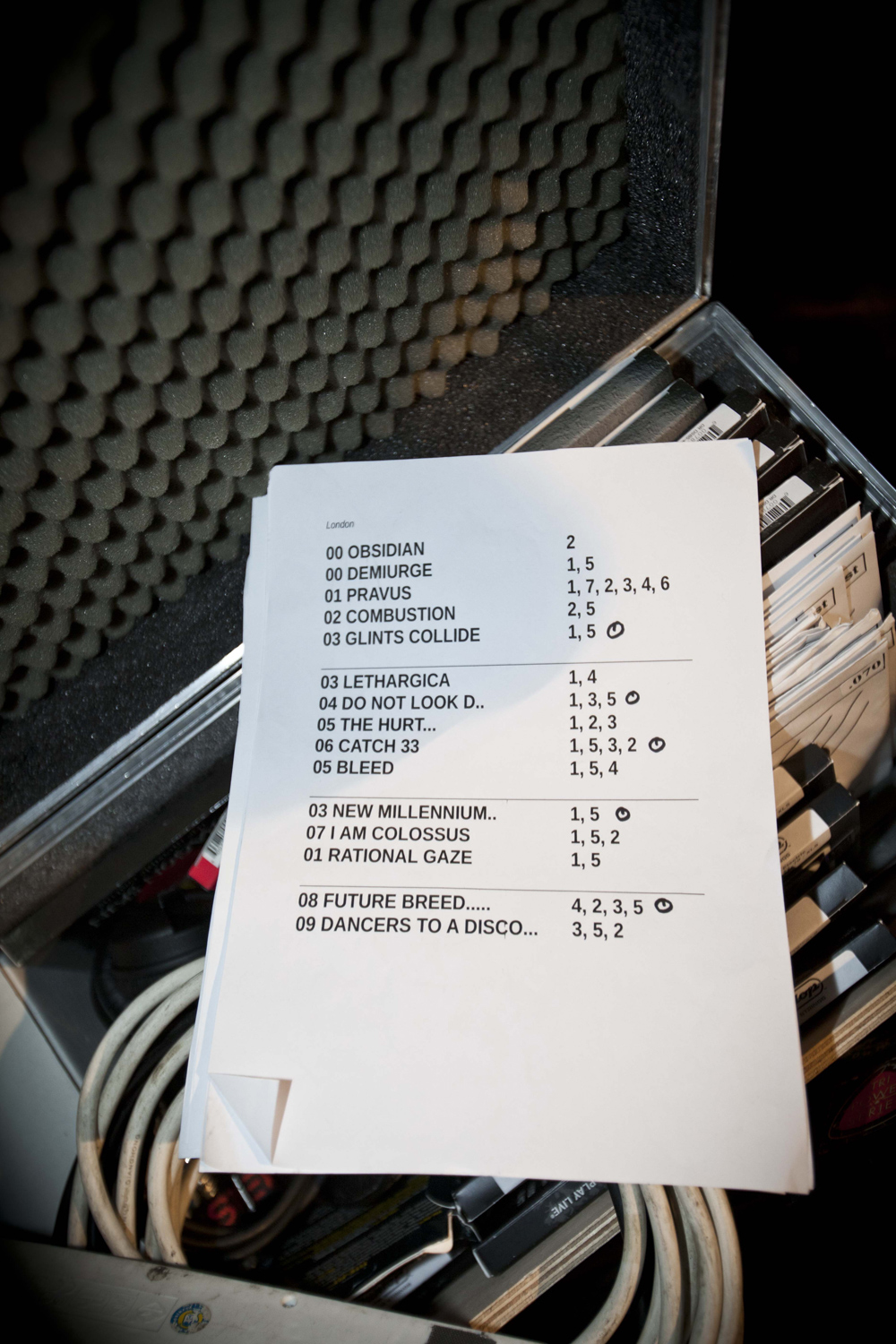

Along with debuting four new tracks—“I Am Colossus,” “Demiurge,” “Do Not Look Down” and “The Hurt That Finds You First”—the guys will be treating fans to some lesser-performed gems, like “Dancers to a Discordant System,” from 2008’s obZen, and a 15-minute excerpt from their 2005 concept albu Catch Thirtythree. “We decided to challenge ourselves and think about what songs we hadn’t played that we’d like to,” Hagström says. “We’ve never been this organized with a set list. The first four tracks are right after each other, and then we have a break. We ordered it so that it allows us to have natural breaks and an up-and-down flow to the set. It challenged us, but we’re having a lot of fun playing it.”

This tour also marks the first time that the entire band is using in-ear monitors with a click track, allowing each member to hear the song lead-in counts while offering no audible preparation for the audience. So when out of nowhere Meshuggah launch into one of their crushing grooves, it’s like getting dropped into a stampede of elephants. “We were a little nervous because of all the technology coming into play,” Hagström admits. “But we also feel like we’re finally doing it properly. We were really out to structure the dynamics and go for a thought-out show with a good overall vibe.”

As Hagström waits for the Ibanez crew to set up the cameras for the demo, he gives us the rundown of the new production-model M8M. The eight-string was modeled after the custom-shop guitars Ibanez created for Meshuggah eight years ago, which have since become Hagström and Thordendal’s workhorses. Thordendal sent his original to an Ibanez factory in Japan, where luthiers cataloged every spec of the custom guitar, including the Lundgren Model M8 pickup, alder body, and 29.4-inch maple/bubinga through-neck. When the guitarists received the first M8M prototypes, they were unexpectedly surprised by the results. “It’s basically the same guitar, but for some reason they are actually a little better than our original custom-shop versions,” Thordendal says. “Which is really weird, because usually it’s the other way around.”

We stay for the first few takes of Hagström’s demo, then retreat downstairs to the bar for a little refreshment.

5 p.m. Soundcheck

The scene at the House of Blues backstage lounge is not unlike a typical Saturday afternoon in many living rooms across the States. The band members are casually sprawled across the immense couches to watch the final moments of Game 3 of the Western Conference NBA quarterfinals. Kidman, who appears to be fighting a head cold, quietly sips on a cup of tea and taps away on his laptop, while Hagström, Lövgren, Haake and Thordendal munch on nachos and cheer as the Los Angeles Clippers narrowly clinch a one-point victory over the Memphis Grizzlies.

When the game ends, the discussion turns to Koloss and a theory that’s been making its way around the internet. Though the new album contains 54 minutes of eight-string chugging, otherworldly solos and hypnotic grooves, it is still relatively restrained compared to previous Meshuggah albums. Online critics and bloggers have surmised that Meshuggah took this direction on Koloss after experiencing the difficulty of replicating obZen’s extremely technical tracks onstage. The band members are quick to dispel any such conjecture.

“Actually, I’d say that the songs on Koloss are as challenging as anything off obZen,” Thordendal says without hesitation. “They might sound easier, but they aren’t. They’re just hard…in a different way.”

“‘Bleed’ and ‘Dancers to a Discordant System’ are the most challenging [tracks on obZen], but we can still play them,” Hagström adds. “But going into Koloss, we didn’t think about that. Even though we might say to ourselves, ‘It would be nice if we’d write some songs that we can actually play live,’ it doesn’t come into effect when we’re writing; it’s just about creating cool shit.”

As Hagström is quick to point out, Koloss still has its share of wickedly complicated barn burners, namely “The Demon’s Name Is Surveillance.” “‘That’s, like, the ‘Bleed’ on the new record,” he says. “We’re not even playing that live yet, because I still have to really work to get the techniques and mechanics of it down.” While the remainder of the album’s tracks might not present the same technical challenges as the relentless, shifting riffs of “The Demon’s Name Is Surveillance,” a deceptively large amount of attention is required for the band to nail the right groove and vibe.

Keen to illustrate this point, Hagström launches into a story about how even these apparently simple songs fooled one of their own, Fredrik Haake, who is Tomas’ cousin and also a drummer. Fredrik, who is lighting director and operator on this tour, manipulates two lighting control consoles connected to the onstage lighting rig. Because he’s essentially “playing” the lights on the fly in conjunction with the music, he has to know each song cold. “Fredrik was saying that he thought the new songs wouldn’t be hard to learn,” Hagström says. “But then when he actually had to learn them it was a totally different experience. He’s had to take notations on the new tracks, which is something he’s never had to do before.”

Yet for all the complexity of their music, Meshuggah make it look easy. When their manager enters the room to inform the band it’s time to soundcheck, the guys leisurely ready themselves and make their way downstairs to the stage. Haake arrives first and runs through a series of drum patterns. The renowned drummer is focused and measured with every roll, crash and double-kick. Even during the mundane exercise of checking levels, his virtuoso, fluid and seemingly effortless technique is stunning. Hagström, Lövgren and Thordendal soon appear with axes in hand, and Kidman follows shortly after.

After a few minutes dedicated to dialing-in the guitarist’s sounds—which all emanate from Fractal Axe-Fx guitar and effect processor units that feed out to the venue’s P.A. system—the band rips into “Combustion,” from obZen. The sound is immense and instantly overwhelms the venue to the point that the staff, crew and opening–band members cannot help but pause and turn toward the stage.

Kidman stays for one song before retreating to the dressing room. The rest of the members stay behind and spend another 20 minutes working through “Dancers to a Discordant System” until they are pleased with the sound. With that, the theater falls silent and each of Meshuggah’s members departs the stage as nonchalantly as he arrived.

8 p.m. Doors

The sun is just beginning to set, and the fans outside the House of Blues have begun funneling into the venue. Inside, Poland’s Decapitated are preparing to take the stage. The death metal act is splitting warm-up duties with Atlanta-based proggy sludge-metallers Baroness, who will be debuting a few new tracks from their forthcoming CD, Yellow & Green.

We catch some of the opening acts’ sets before making our way backstage to find Thordendal and Hagström, who are digging into some catering. We then retreat to a small backstage room to discuss the particulars surrounding the creation of Koloss. Like some multifaith confessional booth, the room is adorned with religious relics, candles and an immense smiling Buddha.

“It’s kind of perfect, right?” Hagström says of the booth’s confessional-like atmosphere. After pausing for a moment to speculate on what could make one’s face achieve the Buddha’s ecstatic expression (Enlightenment? Orgasm? Hitting the Mega-Ball Lottery?), our conversation lands on the theory that creative forces exist everywhere, all the time, and that you must discover how to best position yourself to receive the information.

“You absolutely have to tune into it,” Hagström says emphatically. “We’ve actually been discussing this a lot. You know those voice memo things on your iPhone? If I had had one of those for the last 20 years to record my ideas when I was walking around, I would have, like, 10 albums. Every really good idea comes during some spur-of-the-moment event. But rarely do you get a whole song from those moments. Usually it’s one idea that you then have to work to build a whole song around, which means sitting down with the guitar and figuring it out. But the initial inspiration is really like the ghost in the machine.”

“You have to just let it come to you,” Thordendal adds. “For me it can happen anywhere. But mundane situations seem to be the best, like riding the commuter train.”

“It’s whatever allows you to put your consciousness on hold,” Hagström continues. “Whether I’m fishing, sitting on the couch watching TV or walking around outside, my mind is not thinking of anything, and then all of a sudden I’m like, ‘Ohhh!’ And then I run home to grab my guitar.”

For all their technical tendencies—like subdividing 4/4 riffs into unexpected patterns and infusing them with progressive, alien-sounding solos—Meshuggah have always been blessed with heavy, mesmerizing grooves. These, like the distinct attack of Thordendal and Hagström’s picks against their strings, have been an inspiration to the new crop of djent metal bands, whose young guitarists have unequivocally cited the Swedish five-piece as evolutionary ground zero. With the reserved poise of elder statesmen, Thordendal and Hagström have quietly accepted this praise and expressed their support of these young bands. But the pair also harbors concerns that some people may be missing the point: that technicality should always serve the groove.

“People get so caught up with the technical aspect of things,” Hagström says. “If you’re just after sheer speed and technical prowess, there are a lot of other bands that would be more interesting to watch than us. But the technical aspects are never something we seek out. They’re a byproduct of what we want to sound like.”

- “In fact, it’s actually disturbing that it becomes so technical,” Thordendal says. “The technical aspects are what cause the problems.”

- “We’ve always been about the groove,” Hagström continues. “Granted, we have a pretty twisted way of approaching how we groove. But it’s not all that big of a deal. Sometimes people think we set out to create these crazy patterns and then make them work. That’s not how it works, because most of the time it sounds like shit with that approach. You just have to find the groove and then work with the weird stuff until it makes sense.”

The way a typical Meshuggah album comes together goes something like this: individual members write fully fleshed-out demos of songs and then present them to Haake, at which time he lays down drums for all tracks. The guitar and bass parts are then recorded, followed by the vocals. When it came time to write the tracks that would become Koloss, Meshuggah attempted to switch up their approach in two ways. One stuck; the other didn’t.

“At first we decided to try to go into a jam situation with riffs,” Hagström says. “We started with ‘Swarm.’ I had written stuff for it, but it wasn’t close to being finished. So we got together and felt it out as a band.” The collaboration was a success, as heard in the track’s seething, relentless guitar attack and stinging solo, which cleverly evokes a swarm of insects.

“That solo was so crazy that I almost couldn’t use it,” Thordendal says with a laugh. “It was just so ‘out,’ and honestly, it didn’t sound very good. I had to put so many delays on it. Really, that’s the worst one on the album. But it does sound like a swarm, so I guess it fulfills the function for the song.”

Meshuggah may have hit pay dirt with the group effort that bore “Swarm,” but the collective jam sessions fizzled out nearly as quickly as they began. “It was great, but we just went back to doing what was comfortable,” Hagström says. The rest of the tracks were composed individually by the members and presented to the group as full demos. While the jam-session writing approach didn’t take hold, Meshuggah’s decision to break from tradition and lay down all tracks for each song before moving on to the next proved to be a more lasting endeavor.

“Normally we record drums for all tracks, then guitars and so on,” Hagström says. “But this time, we recorded the drums, then guitars for the same song. So with a track like ‘Swarm,’ we had finished bass, drums and guitars before we even had half of the stuff for the rest of the album done. I think it helped us to get more perspective on the songs, because we had time to be with them during the rest of recording.”

As has been the case for years, for the writing and recording of Koloss, Thordendal and Hagström used a relatively minimal setup consisting of an arsenal of eight-string Ibanez guitars, including Icemans and the M8M models, Fractal Audio Axe-Fx preamps and Cubase recording software. While there may not be many moving parts in the setup, the combination of the Axe-Fx and Cubase allowed for near-endless expandability and experimentation.

“Because of Cubase, even our initial demos are pretty extensive,” Hagström says. “We do bass, guitar and vocal melodies, and programmed drums with Superior Drummer from the Drumkit from Hell [software by Toontrack]. In fact, Fredrik and I wrote more drum riffs on this album than Tomas. Because Fredrik is also a drummer, he knows how you handle the sticks and what is actually physically possible for a drummer to play. But I don’t know that shit. I go crazy with programming.”

“He’s like the [four-armed Indian deity] Shiva on drums,” Thordendal says with a laugh. “But the drums are really so important to our music. They need to be exactly what they are. We can’t say, ‘Here’s the riff, just jam some drums with it.’ When I hear the riff in my head, the drums are there too.”

For his part, Haake had a hand in writing a couple tracks for the new album, including “Do Not Look Down.” To create an illustration that the guitarists could refine, Haake programmed the initial drum track and got Hagström to lay down a riff, which the drummer then cut and stretched to build out the rest of the song. “It turned into the most funky track we’ve ever done,” Hagström says. “It’s like funk-rock Meshuggah.”

“That lead is almost embarrassing,” Thordendal says of the major pentatonic line he plays over the minor riff. “I never play like that, but the song craved a groovy rock-style lead.”

Meshuggah’s relationship with the Cubase software is not only crucial to the demoing process but also defines the band’s sound on record, much to the surprise of their more gear-headed fans. “All the guitars you hear on the album are Cubase with the Amp Rack plug-in for the tone,” Hagström says. “It’s funny, because people are always like, ‘Your guitars sound sick! What amps are you using?’ We’re like, ‘Cubase,’ and they just stare at us.”

10:30 p.m. Showtime

The huge, surreal supermoon is beaming brightly over the House of Blues, which at this hour has reached full capacity. Decapitated and Baroness have each concluded their sets, which, while powerful in their own right, have only served to whet the audience’s appetite for something even heavier. The alcohol is flowing and every possible vantage point of the stage is packed with L.A.’s metal-loving finest, who are periodically breaking into chants: “Mesh. Ugg. Ah! Mesh. Ugg. Ah!”

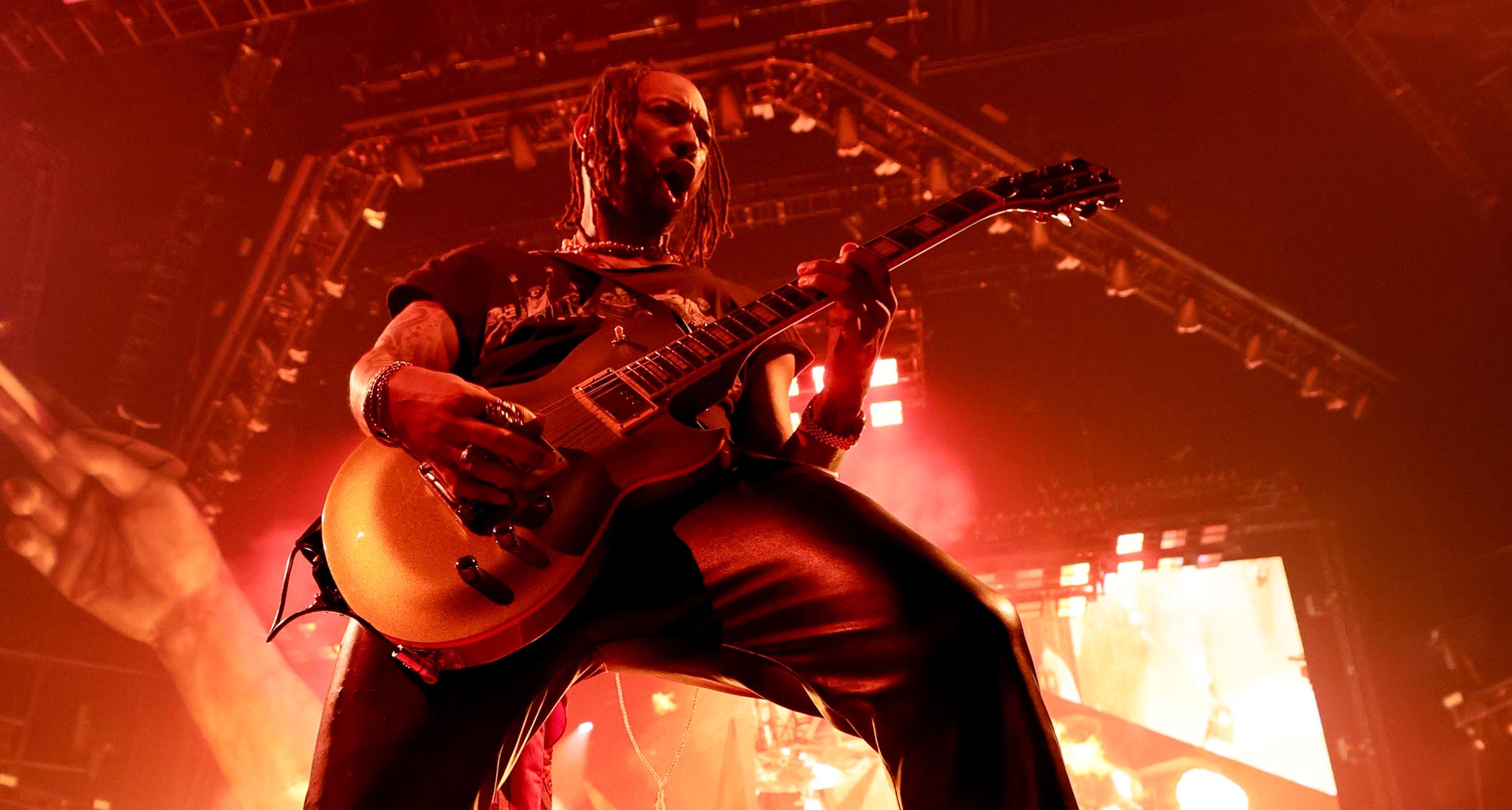

Upstairs, the band has retreated to its dressing room for a moment of privacy to prepare for the impending onslaught. Mårten and Fredrik emerge first, with Ibanez eight-strings in hand, to pose for some last-minute setups with our photographer. We all walk down the back stairs and position ourselves on the side of the stage. While our photographer grabs a few final shots, the rest of the band arrives. Kidman runs through final vocal warm-ups, which consist of a mix of slow growls and quick “Hey! Hey! Hey!” shouts. Haake stands with sticks in hand, loosening his wrists in circular motions and a few air-drumming runs. Lövgren pounds away on his bass along with Meshuggah’s opening music, which is, inexplicably, Rod Stewart’s disco hit “Da Ya Think I’m Sexy.”

As the lights dim and Stewart’s endless jam fades away, we part ways with the band and hustle out a side stage door just as Meshuggah take their positions onstage and start crunching out the slow chords to the instrumental “Obsidian,” from 2006’s Nothing. The crowd is on its feet as the band ratchets up the tension before launching into a crushing rendition of “Demiurge.” As the lights switch from bright white to blood red, Kidman unleashes his growled lyrics “Writhing and embraced!” The crowd lurches forward and fragments into wild and flailing pits.

The band is scarily tight and appears larger-than-life under the bombastic, dynamic light show. As we push closer toward the stage, we take a quick survey of the audience. Not one person is sitting down, including Tool’s drummer Danny Carey, who is leaning over the center-stage balcony, pounding his fist into the air and headbanging with a huge grin on his face. Between the colossal musical force coming from the stage and the feverish energy of the crowd, a synchronization begins to take place, which brings to mind something Thordendal said in passing earlier today.

“Everything has been a big experiment,” he said. “I don’t even know where it comes from, but it’s all out there. You just build riff after riff. And then you begin to see exactly what’s happening, and then you start to see the big picture, which is what you were looking for in the first place.”