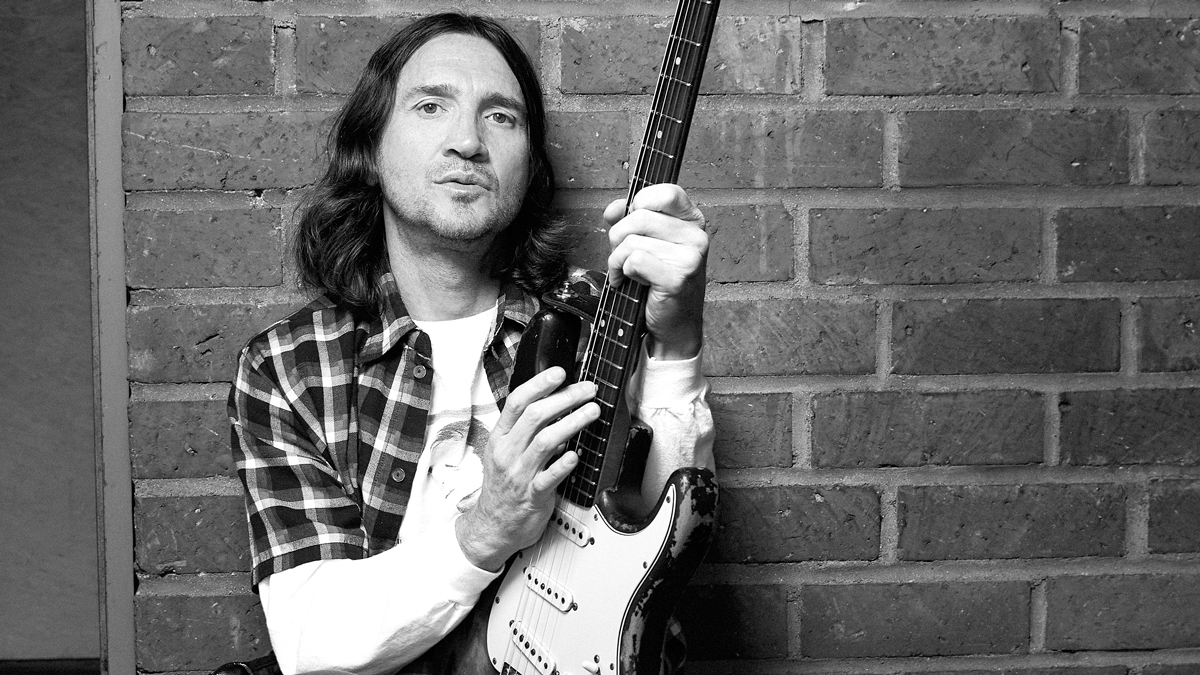

John Frusciante’s 10 best Red Hot Chili Peppers guitar moments

The RHCP guitarist's finest recordings, as voted by you – there's no Give It Away but plenty of deep cuts…

When we asked Total Guitar readers to choose their favourite Chilis songs featuring John Frusciante on guitar, thousands of votes flooded in.

Here we present the top 10 – with analysis of what John brought to each track. Some of the band’s biggest hits are missing – including Give It Away, The Zephyr Song and By the Way. But in these 10 songs, the brilliance of John Frusciante shines bright.

10. Californication

The intro to the title track of the Chilis’ 1999 masterpiece uses open-position A minor and F major arpeggios with open string notes to add colour – Flea’s bass plays the melodic fills Frusciante would normally add himself. The end of the verse builds momentum by changing chords twice as often, through C-G-F-Dm.

John plays soft, arpeggiated voicings, so when he starts aggressively strumming Am and Fmaj7, there’s a real lift. The solo changes key to F# minor, with a tone more typical of funk rhythm than rock lead. John repeats and develops simple melodic ideas, varying the rhythm or changing the ending, to make a satisfying break without the need for speed.

9. I Could Have Lied

The acoustic part opens, coincidentally, with the same notes as Metallica’s One: a B5 powerchord at the 2nd fret, alternating the open D string. The mysterious chord ending the first chorus is G6, played as an E-shape barre at the 3rd fret with the B and E strings left open.

The acoustic was a Martin D-28, reportedly with the G string missing entirely, and the solo is distinctively John’s ’59 Strat.

Frusciante recorded much of Blood Sugar Sex Magik plugged straight into the desk even for solos, distorted by overloading the input, but this sounds more like an amp – perhaps the 200-watt Marshall Major and 100-watt Marshall Super Bass, or even the cheap Fender H.O.T. practice amp John unexpectedly loved.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

8. Dani California

Hendrix influences are front and centre here. In the verses, John embellishes each chord with a Jimi-style hammer-on and pull-off lick. The outro solo is built around a four-note theme that recalls Hendrix’s Purple Haze intro, complete with fuzz. Frusciante plays two-bar call-and-response phrases.

Each opens with the same four notes (which makes it memorable) and finishes with a unique answering phrase (which keeps it interesting). Next, John kicks in his wah and goes for broke with a rapid repeating lick that explodes into tremolo picking and a climactic descending minor pentatonic run.

7. Soul to Squeeze

This track was left off Blood Sugar Sex Magik but recorded at the same time, and you can hear John’s ultra-clean tone straight into the desk on the intro lead licks. His Boss CE-1, normally used to split the signal into different amps, creates the swirling intro tone while he riffs around an open A chord with A major pentatonic fills.

The slide solo is double tracked with each take panned hard left and right, an experience best enjoyed with headphones. Subtle differences between the takes give it personality, like at 2:38 when the slide rattles the strings of the left guitar.

6. Don’t Forget Me

Frusciante solos for almost all of this song, one of the 21st century’s first guitar hero moments. He gave TG the lowdown on how it was recorded back in 2002: the trebly lead tone comes from his Ibanez WH10 wah, left in a fairly forward position, and an envelope filter.

His Line 6 Delay Modeler was in analogue mode, constantly on the verge of self-oscillation, which he controlled with a volume pedal and by adjusting the DL4’s feedback control on the fly. The delay repeats are set to triplets while John picks 16th notes, making the tremolo picking sound faster than it is.

5. Can’t Stop

There’s an art to playing fat single-note funk lines, exemplified on this track, which is to mute every string except the one you’re currently playing with your fretting hand. This leaves John free to strum aggressively across all six strings, creating a fat tone and extra excitement from the white noise of the pick on the muted strings.

When Anthony Keidis sings the verse, the guitar tone suddenly becomes anaemic. A ton of mid and bass is pulled out to make space for the vocal, but you won’t notice unless you listen for it because your brain tells you it’s still the same big guitar you just heard in isolation.

When recording By the Way, John made use of the core Blood Sugar Sex Magik amps, the 200-watt Marshall Major and 100-watt Marshall Super Bass. But rather than run them together as he has for most of his career, he typically used one in combination with another amp, often a blackface Fender Showman with a Marshall cab.

John ditched the ’58 Strat from the Californication sessions for a ’62, saying: “That ’58 has a bit of a cleaner sound and it always seemed to sound better for what I wanted on Califonication, but for this album, the ’62 just sounded right straight away – the sustain’s better.”

Unusually for Frusciante, this track mainly uses the bridge pickup. According to his tech Dave Lee, the pickups in that guitar came from a modern Fender American Standard Strat. Lee did not tell John that’s what they were, but Frusciante chose them after trying various alternatives.

4. Scar Tissue

This intro is popular with beginners because you can play it as a straightforward fingerpicking part, but Frusciante uses a pick, muting open strings with his fretting hand as always. The riff is based on playing the root note of each chord followed by the third an octave higher, using mainly F and D minor, with C making a brief appearance in between.

Like all Frusciante’s rhythm parts, it’s deceptively complex, although it’s not necessary to copy him verbatim. His relaxed feel on live performances suggests he was somewhat jamming the original, and it needn’t be played identically every time.

The clean tones on the Californication album came from a Fender Showman amp, and the tone is otherwise extremely dry. You might add some compression to mimic the response of the Fender amp at high volume, but not much else. The slide solo is another lesson in simplicity, a melody played entirely on one string that makes an ideal introduction to learning the technique.

That simplicity was vital for John, who commented later that the process of making his first solo album was a journey to “playing with just a minimum amount of notes,” which informed his playing when he returned to the Chilis.

“It’s a perfect place when you get to that point,” he said. “That’s why I like the Californication record, because I feel like it’s the result of all that searching. When I hear it, I hear someone trying the best they can at that time, whereas on Blood Sugar Sex Magik I was capable of playing much more than I did.”

3. Wet Sand

On 2002 album By the Way, Frusciante began moving away from the single-note funk riffs towards full chord voicings, requiring cleaner tones. “I was playing a lot bigger, denser chords than just your standard triads,” he said. “I wanted all those intervals to come through clearly. I’m not really into distortion, except for solos.”

Four years later, on Wet Sand from Stadium Arcadium, this transition was completed, with the cleanest tones permitting layers of strumming.

There’s a bit of movement courtesy of a real Leslie rotary speaker, and as John said, some guitar tracks were mixed partially out of phase – “to make the guitars seem to project out in front of the speakers”. That’s not the end of the trickery: a tremolo effect on the verse lead lines makes the picking sound even more frantic.

The outro solo is the antithesis of shred, a passionate pentatonic outburst based on long notes and slow bends. The tone is clearer than the Big Muff Pi fuzz sound he uses on Strip My Mind, probably from the Boss DS-2 he also used for the harmonies in the last chorus of Dani California.

Arguably the most interesting sound, though, is pushed to the background. Starting at 4:00 and continuing under the outro solo, there’s a busy part that sounds similar to a harpsichord.

After tracking the original arpeggiated chords, John slowed the tape down to record a harmony part a third higher using his bridge pickup. A pleased Frusciante said at the time, “I’m convinced that’s what Hendrix did on Burning of the Midnight Lamp.”

2. Snow (Hey Oh)

The third single from Stadium Arcadium is perhaps the most succinct expression of Frusciante’s approach to playing chords.

There’s one Hendrix-style flick that is a huge part of Frusciante’s style, and for Snow he finally built an entire riff around it. To play it, you pick a note and immediately hammer onto and pull off from the note two frets higher. You finish by landing on the next note down the pentatonic scale from where you started. It’s also the basis for the verse fills in Dani California and Under the Bridge. For Snow, John plays this fill over every chord in the progression.

Stadium Arcadium saw Frusciante replace the Marshall Super Bass in his recording rig with the Marshall Silver Jubilee 25/50 he has been using live for years, apparently inspired by Slash’s use of the same amp.

The massive organ-like tone from 4:16 on the outro is created with an Electro-Harmonix POG. Then the huge harmonised, distorted chords from 5:09 were tracked painstakingly, as John explains: “I created an articulated arpeggio using three distorted guitar parts, each playing one note of the arpeggio recorded onto a separate track.

“Normally if you tried to play that sort of line with a distortion pedal, you’d get frequency beating and the notes would be indistinct. But this way each note is clear, while giving the impression of being a single guitar.”

It turns out that recording chords one note at a time is not the exclusive preserve of Def Leppard albums after all.

1. Under the Bridge

Undoubtedly the best Hendrix tribute riff of all time, Under the Bridge runs with the chord melody style Jimi showcased on Little Wing. Frusciante, though, leans into awkward C shape barres that Hendrix rarely used.

Under The Bridge is a pleasant introduction to embellishing a chord progression with fingerpicking and melodic fills, if you use a capo on fret 2. For some masochistic reason, Frusciante didn’t use a capo, which makes it an absolute pain to play!

Even the most overused chord progressions sound fresh with a tasteful arrangement and a good song, and there’s no better example than Under the Bridge, in which the verse largely uses the same I-V-vi-IV chord progression that’s been battered to death in more pop songs than any other, sometimes with a I-V-vi-iii-IV variation.

Frusciante’s great rhythm, and just the right amount of ornamentation, keep the progression sounding as fresh as when it rolled out of Pachelbel’s quill in 1680. This is helped by the brooding D to F# major chord sequence of the intro, which was also a favourite of Kurt Cobain’s.

When the song shifts to E major for the verses, the mood lifts noticeably. Although less discernably funky than the rest of the album, Frusciante throws in some funk signature moves: the D-shape major triad in the chorus with a 16th note rhythm feels like something from a James Brown record, and his occasional scratching on muted strings helps the entire track to groove.

Part of the appeal of Under the Bridge is that it defies conventional pop song structure. After the second chorus, the song never returns to any of the earlier sections. The last 90 seconds can be seen as one giant outro. The melody and lyrics nod to what’s gone before, but musically it’s a different world. The key shifts to A, following an unusual progression from A major to A minor, followed by G6 and Fmaj7, with the high E ringing open to unify the sequence.

Despite this being the most obviously Hendrix-inspired track on Blood Sugar Sex Magik, Frusciante didn’t record the intro on the Strat he used for most of the album, instead choosing the 1966 Jaguar seen in this song’s video.

Although the tone sounds clean, this style of playing works best with the amp on the edge of breakup. Sparkling clean tones can be too brittle for this approach. Frusciante keeps his Marshalls cooking to avoid that problem, or deliberately overloads the input when recording direct into an analogue desk.

30 years on, Under The Bridge remains Frusciante’s signature. Flea has admitted that the song lost its spark live when the band performed it with Dave Navarro in the ’90s. It needs the chemistry of the line-up that recorded it to work, as anyone who remembers the 1998 version by All Saints will attest.

While the Chilis’ music has been hugely influential on both mainstream and alternative rock since, Under the Bridge remains largely untouched. It’s such a spare arrangement, such a distinctive guitar part, and such a vulnerable lyric that it’s almost immune to imitation.

Jenna writes for Total Guitar and Guitar World, and is the former classic rock columnist for Guitar Techniques. She studied with Guthrie Govan at BIMM, and has taught guitar for 15 years. She's toured in 10 countries and played on a Top 10 album (in Sweden).