“John Mayall’s ability to nurture blues guitar prodigies is comparable to Yoda’s knack for training hot Jedi prospects”: From Eric Clapton to Peter Green, Mick Taylor and more – a guide to blues legend John Mayall’s ’60s Bluesbreakers guitarists

The Bluesbreakers remained a unique force in British blues throughout the decade, thanks to its late leader’s unfailing ability to pick breathtaking bandmates

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The late John Mayall’s ability to nurture blues guitar prodigies is comparable to Yoda’s knack for training hot Jedi prospects. Chiefly known for giving Eric Clapton, Peter Green and Mick Taylor the opportunity to shine in the 1960s, Mayall’s eye for talent proved powerfully sharp both before and after the star trio’s respective stints in his legendary outfit the Bluesbreakers.

The band’s first decade remains of central importance, thanks to the seismic influence of albums like Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton, A Hard Road and Crusade. Moreover, Mayall’s artistic development from the band’s formation in 1963 to the end of the ‘60s uncovers a trailblazing trajectory of pioneering, popularizing, then progressing the blues with more experimental records.

Join us now for a whistle-stop guide to the most iconic era of Mayall’s six-stringers.

(All Mayall quotes are taken from his autobiography Blues From Laurel Canyon – My Life As A Bluesman.)

Bernie Watson – 1963-64

Cyril Davies was a leading light of the ’60s, along with Mayall and Alexis Korner. Mayall said that Bernie Watson, who came from Davies’ R&B All Stars, “professed disdain for anything other than classical music” and yet played blues “with such emotion and finesse you’d swear it was his forte.”

Watson’s sharp solo on the Bluesbreakers’ debut single Crawling Up A Hill proves the point.

Davy Graham – 1964

Besides towering achievements as a folk pioneer – penning classic fingerstyle instrumental Angi, which popularized DADGAD tuning – Graham enjoyed a fleeting stint as Mayall’s live guitarist on at least one occasion.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Inserting a pickup into the soundhole of his acoustic guitar, Graham’s performance was described as “spot on” by an eyewitness.

Roger Dean – 1964-65

When brief incumbent John Gilbey proved a bad fit, Mayall recruited Dean, a country and western fan unfamiliar with the blues.

Though the band leader considered Dean a “very accomplished technician,” he felt that on studio recordings, “the fact that he wasn’t a natural blues player was obvious.”

Eric Clapton – 1965-66

Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton (aka The Beano Album) is revered as a classic – but the track that sold Mayall on Clapton was the lesser-known Got To Hurry. It was the B-side to the Yardbirds’ For Your Love – the poppy single which had prompted Clapton to quit the band.

Hearing the track, Mayall “felt a surge of excitement,” and explained: “I could almost feel Eric talking to me through his solos, which conveyed the power and emotion of great blues guitarists like Freddie King.” Clapton was working on a building site when Mayall tracked him down. In a tribute after Mayall’s death, Clapton thanked him “for rescuing me from oblivion”.

Mayall later revealed the young guitarist’s groundbreaking approach to recording Blues Breakers, saying that engineer Gus Dudgeon “was horrified that Eric intended to play through his Marshall amp at full volume, [but] Eric stood his ground.” Mayall’s pivotal influence encouraged Clapton to record his first vocal performance on Ramblin’ On My Mind.

Clapton’s tenure proved as tempestuous as it was influential prior to his permanent departure in July 1966, to form Cream with Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce – the latter of whom was briefly a Bluesbreaker himself in 1965.

Peter Green – 1965, 66-67

When Clapton quit to travel across Europe in summer 1965, Mayall promised to allow him to rejoin if he wanted. As he held an onstage audition to find a replacement, Green asked to take part. Plugging his Harmony Meteor guitar into Mayall’s amp, Green delivered “a revelation” and “the purest tone I’d heard since Eric,” Mayall enthused.

While being ousted on Clapton’s return in December that year, Green was Mayall’s first and only choice after Clapton’s final exit. The older player dubbed Green “a bona fide blues legend,” praising the “savage genius” of his work on the So Many Roads single.

He even said he preferred 1967’s A Hard Road to the Clapton album, due to its variety – evidenced by the Latin-style percussion on Green’s stunning showcase The Supernatural.

Green left June 1967, forming Fleetwood Mac with ex-Bluesbreakers Mick Fleetwood and John McVie. But he contributed some tasteful acoustic slide work on Mayall’s 1969 solo single Picture On The Wall.

Mick Taylor – 1967-69

Mayall first encountered Taylor in April 1966, when the 18-year-old volunteered his services at at a gig in Hatfield after Clapton failed to arrive. Taylor’s “terrific” playing made a powerful impression on the band leader – but he vanished before phone numbers could be exchanged.

Hoping to reconnect on Green’s departure, Mayall’s ‘guitarist wanted’ ad in Melody Maker brought Taylor into the ranks. A month after joining in June ‘67, the new boy was adding stinging lead work to the raw, exciting Crusade album, cut in 11 breakneck hours.

He developed as a soloist at a remarkable pace through 1968’s experimental Bare Wires and Blues From Laurel Canyon. Onstage, “anything Mick played raised the roof,” Mayall recalled – an impressive feat with the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Otis Rush sitting in during the period.

Dissolving the line-up in June 1969 to pursue an acoustic direction, Mayall recommended Taylor to Mick Jagger when the Rolling Stones vocalist sought his advice regarding a replacement for Brian Jones.

Jon Mark – 1969-70

Seeking a break from the guitar, organ, bass and drums lineups he’d favored, Mayall took his experimentation to a bold extreme in 1969 after being inspired by Jimmy Giuffre’s stripped-down, drum-free combo seen in 1958 concert film Jazz On A Summer’s Day.

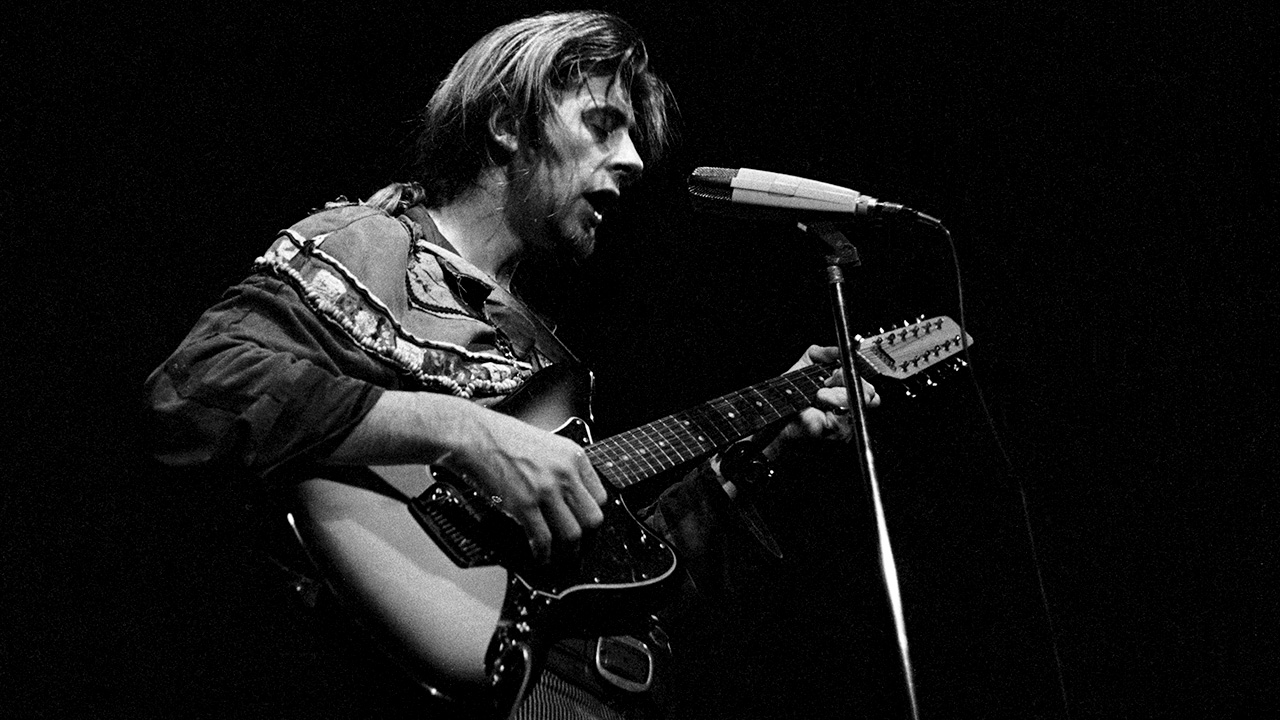

He recruited acoustic fingerstyle guitarist Mark after first meeting him as a member of Marianne Faithfull’s band. The gamble paid off, most demonstrably on The Turning Point, recorded live at New York’s legendary Filmore East – described by Mayall as “a high point in my career.”

Mark’s nimble licks on I’m Gonna Fight For You J.B. are a mellow delight. He’s less upfront on 1970 studio follow-up Empty Rooms; but his eloquent, minor-key solo on Counting The Days is as arresting as anything played by his plugged-in predecessors.

When Mayall’s muse took him in a different direction in summer 1970, Mark and flautist/saxophonist Johnny Almond kept it low-key and groovy with Mark-Almond (not to be confused with the Soft Cell vocalist).

Rich Davenport is guitarist and vocalist with punk/ska punk/punky reggae merchants Vicious Bishop, and is a former member of Radio Stars, Atomkraft, and Martin Gordon’s Mammals. He swears by Orange amps and pedals, which is entirely appropriate for a ginger. In addition to making loud noises, he’s also written about loud noises for Classic Rock, Record Collector, Vive Le Rock, and Rock Candy. He’s interviewed such six-stringers as Ritchie Blackmore, Joe Bonamassa, Michael Schenker, Ty Tabor (Kings X), Peter Tork (The Monkees), Scott Gorham (Thin Lizzy), Pat McManus, Steve Hunter (Alice Cooper, Lou Reed), Ed King (Lynyrd Skynyrd), Vivian Campbell (Dio, Def Leppard), George Lynch (Dokken), Steve Lukather (Toto) and Lita Ford.