“I would call our approach organized chaos, but it drove Allan Holdsworth up the wall”: John Wetton has been the bass force behind a peak-period King Crimson lineup and two prog rock supergroups

A veteran of one of King Crimson’s classic lineups, John Wetton’s amazing career took him through a host of British prog bands

When it comes to highs and lows, the late John Wetton was a wizard. Onstage with his Asia bandmates – Yes guitarist Steve Howe, drummer Carl Palmer of Emerson Lake & Palmer, and keyboardist Geoff Downes of Yes, Wetton wailed in a tenor singing voice that ranks with any in rock history. At the same time, he issued basslines that complemented his vocals with Baroque-like efficiency.

As if that weren't enough, he frequently underpinned both parts with seismic support tones from his ever-present bass pedals. Highs and lows also describes Wetton's career, a journey that took him through a host of key British rock bands, with numerous trips up the charts and bitter breakups along the way.

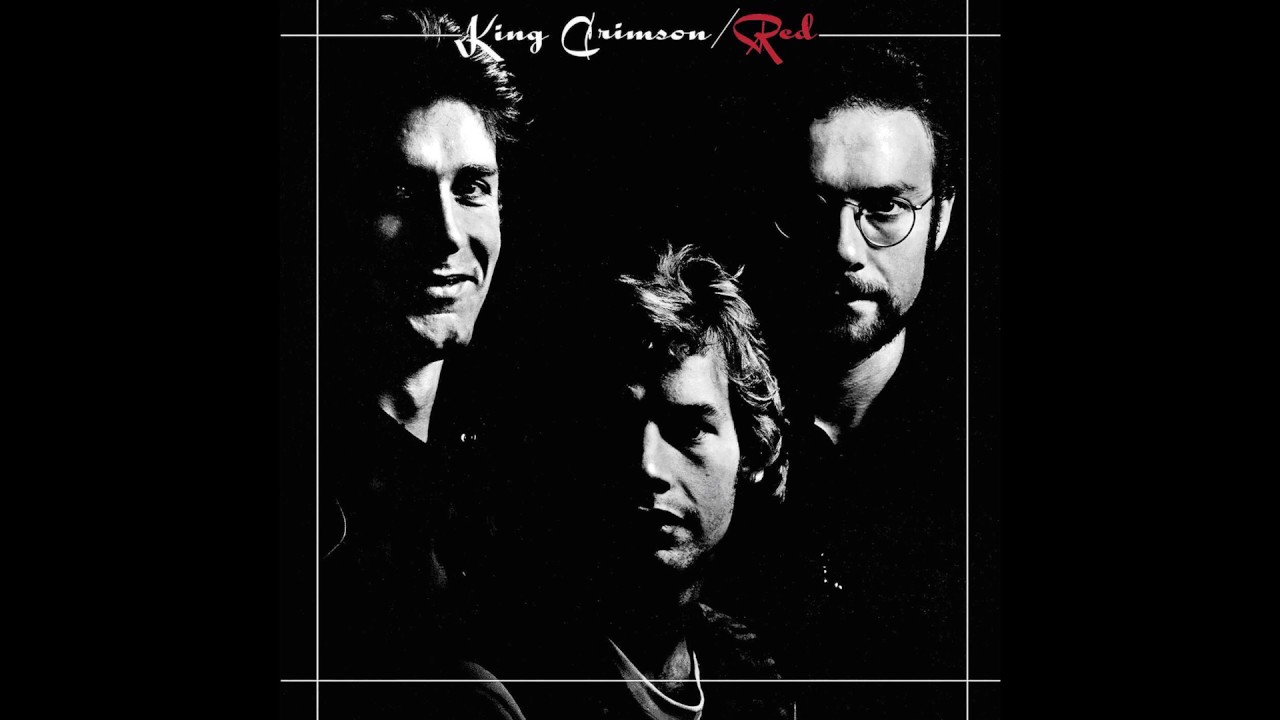

It 1971 Wetton performed and recorded with Mogul Thrash and then became a member of Family gaining prominence in England. This led to an invitation from a re-formed King Crimson, resulting in a peak period for the cult prog-rock band, with albums like Starless and Bible Black and Red.

Following that edition's late-'74 breakup, Wetton toured and recorded with Roxy Music and Uriah Heep before reconnecting with his Crimson rhythm section-mate Bill Bruford to form U.K. in 1977.

Three U.K. albums gave way to Wetton's 1980 solo debut, setting the stage for his role fronting Asia, a period he calls an artistic highpoint. Established in 1981, just as the video era was launching, Asia parlayed its pop-meets-progressive sound into hits like Heat of the Moment, Only Time will Tell, and Don't Cry.

A bout with the bottle led Wetton to be temporarily dismissed from Asia (replaced by Greg Lake). Although the other members quickly took him back, Asia wasn't able to duplicate its initial aces, and the group disbanded in 1985.

By 2000, Wetton had re-teamed with Asia members – first in Carl Palmer in the group Qango, and then with Geoff Downes for the Wetton/Downes album, Icon. Finally, in 2006 the original members convened for a successful reunion tour that stretched into 2007 and yielded the CD/DVD Fantasia: Live in Tokyo.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Asia also began works on Phoenix, the group's first studio album in 25 years, and embarked on another globe trot. The tour was interrupted in August 2007, when Wetton underwent triple bypass heart surgery. Wetton died January 3, 2017, after a battle with cancer. He was 67.

We spoke with Wetton in August 2008, with Asia having resumed touring, to get the lowdown on the prog-rock supergroup’s return.

Let's start with the formation of your bass concept.

“I come from the church and from composers like Bach, but my musical life really began when the Beatles and Beach Boys arrived. They put things into color for me, whereas the roots-rock before them had all been in black and white; it was monotone to my ears, with little melodic or harmonic movement.

“The non-root tones of Paul McCartney and Brian Wilson really appealed to me, because church music does that all the time – especially in hymns, where the bass typically moves all over the place the last time through the chorus.

“Essentially, in those days, when they got tired of playing the same bass part they would write a different one just for fun. That triggered my fascination with the placement of the bassline in the chord, and how it compliments the melody.”

“The way I write most often is to have my bass part moving independently or contrapuntally to what I'm singing in the verses, and then have it move parallel in the choruses, harmonizing the melody line. You can hear that on Easy Money with King Crimson; right through Heat of the Moment and Don't Cry with Asia.”

Would you say your bass voice came together in King Crimson?

“Yes, my bass and my musical voice. While working in Mogul Thrash and Family, I had seen bassists as disparate as Jack Bruce, Harvey Brooks, and Miroslav Vitous, and I continued trying to get my hands around James Jamerson's Motown lines. So at 22, I was quite sure of myself, looking to play as many notes as possible! That fit perfectly with the way Bill Bruford played drums.

“After we found our feet with Larks' Tongues in Aspic, I was especially comfortable with my musical input on Starless and Bible Black and Red. In particular, Starless, from Red, was a high-point for me. It's a sonata form, with my ballad at the start, into the demonic tritone bass guitar lick, which Bill wrote, then all hell breaks loose, and finally we're back to the ballad.”

What sort of tone were you going for in Crimson?

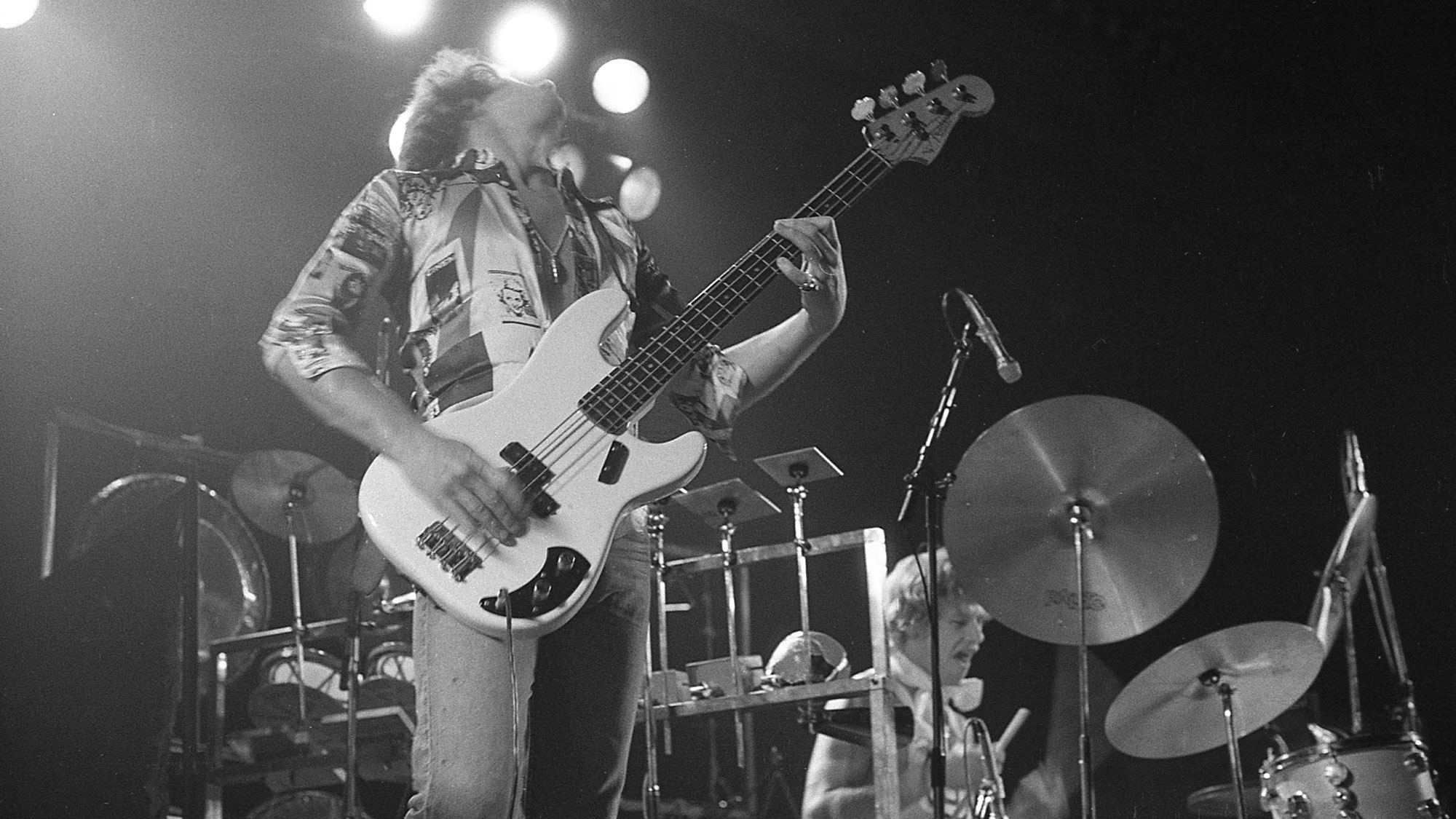

“Being that I was sort of balancing lead and support roles, I went with a sound that was quite sharp. It came courtesy of my fingers, sometimes a pick, my '61 P-Bass, Rotosound strings, a Hiwatt amp, and a cheap Italian wah-wah/fuzz pedal.

“Chris Squire and I were really into the bass tone that Ace Kefford got with the Move; it was like the bottom strings on a piano. That's what we were going after.”

How were you constructing your parts?

“We would have improvisational sections built into the setlist, between the songs, and we'd have a signal, which could come from anyone, that would take us into the next piece. So people really didn't know if we were improvising or playing organised arrangements – but you could do that in the '70s!

“For the improvisations, the only rule was that any member could take the lead at any point and the remaining members had to follow. But there'd be no key centre or chord sequence to go by; it was wide open!”

“There was one improvisation called Trio that had a chord sequence I outlined on bass because Robert Fripp was playing Mellotron. Overall, I would say the improv worked. Some nights it was purely telepathic, but it was never disastrous. Crimson was a great band to be in, but we knew it couldn't last forever.”

How did your bass role evolve for U.K.?

“Coming out of King Crimson, I carried a lot of my busy bass style into Roxy Music, and they didn't mind because they liked stretching out. By the time I finally got back with Bill Bruford in U.K., with guitarist Allan Holdsworth and keyboardist Eddie Jobson, the equation had changed. I was now the frontman, and the focus was on structured songs that left little room for improvisation.

“We were being marketed as a rock band, with videos and opening slots for groups like Van Halen. So bass-wise, I really had to be the anchor; that limited my freedom, but I was okay with it. I would call our approach organized chaos, with an awful lot of energy. On the other hand, the lack of improvisation drove Holdsworth up the wall. Still, I think we made a pretty darn good record.”

“When Allan and Bill left and we became a trio with drummer Terry Bozzio, we moved even further in a vocal and song-oriented direction, and my bass playing became even more functional. The two albums the trio did, along with my 1980 solo debut, Caught in the Crossfire, was my transition toward Asia.”

So Asia came at the right time?

“It couldn't have been better. My zest for music, which had taken 30 years to mature, had come to a head. Plus, I was surrounded by great musicians, the right label, the start of MTV; everything was in place. The only thing that could stop me was the self-destruct button, which happened briefly after two albums, but I got back. What really made Asia a success is that we sacrificed individually to create a true band sound.”

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.