Johnny Marr: “If there’s a room full of guitar players, I’m the last to leave, man. I’m just as hooked as everybody else, and I have been since I was 5 or 6”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For Johnny Marr, the idea to record a 16-song double album came to him in a flash of inspiration. The title Fever Dreams Pts 1-4 simply popped into his head one day, and that was it.

“That title solved a lot of problems for me,” he says. “First off, it’s a great title. If I just called it Fever Dreams, you know, that’s good, but it’s not that good. Fever Dreams Parts 1-4 makes you go, ‘OK, what’s that all about?’ It made me think that – ‘All right, what’s this business of four?’

“So I had to work backward from the title, and immediately I realized, ‘All right, it’s got to be a double album, and we can release it in stages.’” He laughs. “The record company thought I was a marketing genius, but it was purely because I had this title.

From there, all Marr needed was enough songs to match the expansive nature of his concept. Fortunately, the British guitar legend found that he had plenty of time on his hands.

After wrapping a 2019 tour in support of his previous album, Call the Comet, he began work on new demos just as the Covid pandemic forced much of the world into lockdown mode. “I had already planned to make the record anyway, so in a funny way I was kind of fortunate in my timing,” he says.

During this period, the only project that conflicted with Marr’s album schedule was his work with composer Han Zimmer on the soundtrack to the new James Bond film, No Time to Die. It’s their third collaboration, a relationship that began with the dream-based movie Inception in 2010, and continued five years later with The Amazing Spider-Man 2.

“I worked on the Bond film for a few months, but even then I was still able to write songs for my album,” Marr says. “As most people no doubt know, there’s plenty of downtime when making movies.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The first major band I joined was Sister Ray. I wanted to play with them because they sounded like a cross between the Stooges and Hawkwind

Although the guitarist insists he was dead set against making a straight-up Covid-influenced album (“that would come off as dated very quickly”), he admits the day-to-day experience of recording in relative seclusion subconsciously permeated his lyrics.

“I wanted to avoid being too direct about the state of the world, singing about stores being closed and all that,” he says, “but a lot of the album is about how I perceive things, and I made the leap to presume that my audience might be feeling the same way.”

He cites the dark and dramatic groover All These Days as an example: “On that I sing, ‘Drinking with my shadow / escape the sensory / another day tomorrow, tomorrow, endlessly.’ A lot of people were doing that, sitting and drinking on their own late at night going, ‘What’s tomorrow going to bring?’” Similarly, there’s the surging disco-pop gem Night and Day, which finds Marr singing, “Just want to breathe in the hot spots / it’s all TikTok to me / stop the clocks, please.”

“That was being really informed by all the imagery I was seeing from your country in the United States on the television,” he notes. “The album is littered with all these references without being too overt to the point of losing the poetic sensibilities, I think.”

Growing up in the ‘70s, one of the Ten Commandments of Guitar was, “Thou shalt be like Keith Richards” – you know, be the engine of the band

Taken as a whole, Fever Dreams Pts 1-4 is something of a masterstroke – a meticulously plotted 70-minute opus that breezes by like a record half its length. Throughout much of the album, Marr surrounds his songs with au courant electronic rhythms while drizzling his arrangements with the kinds of sweeping, kaleidoscopic guitar textures that have been his calling card since the early days of the Smiths.

Whether he’s dabbling in driving electro-disco (Spirit, Power & Soul), getting introspective inside sophisticated balladry (Rubicon), rocking a rootsy rave-up (Tenement Time) or luxuriating in arty dream anthems (Ariel, Sensory Street), his rousing – and at times, symphonic – six and 12-string guitar treatments brim with commanding authority and crafty individuality.

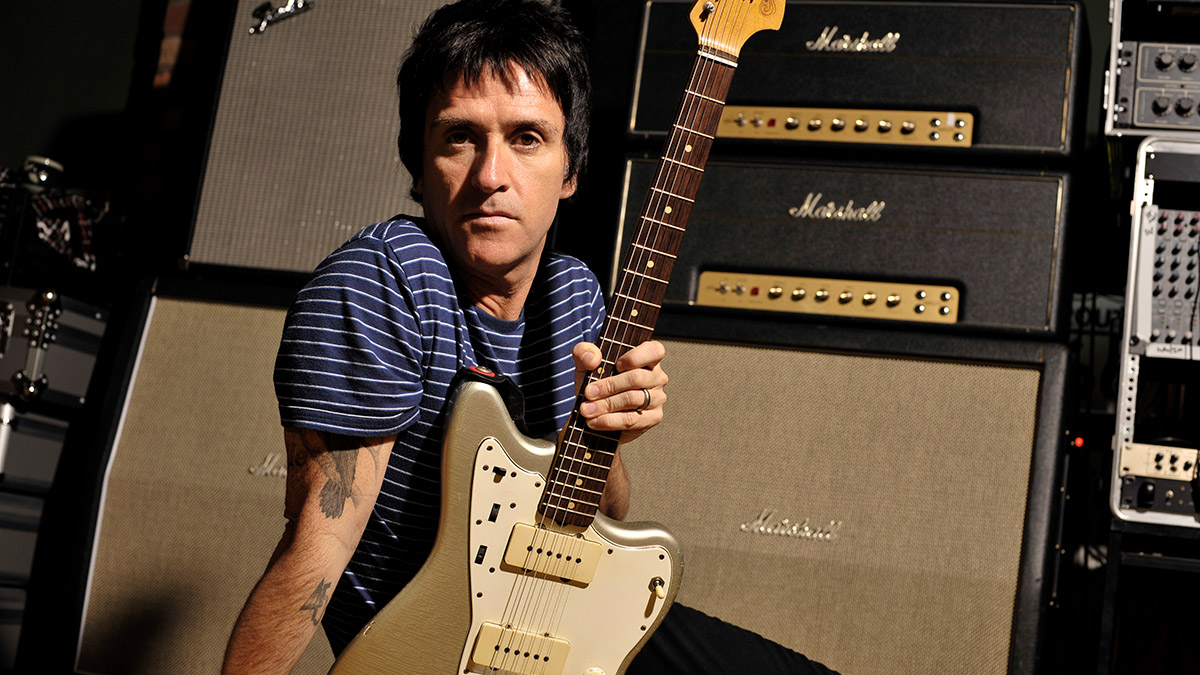

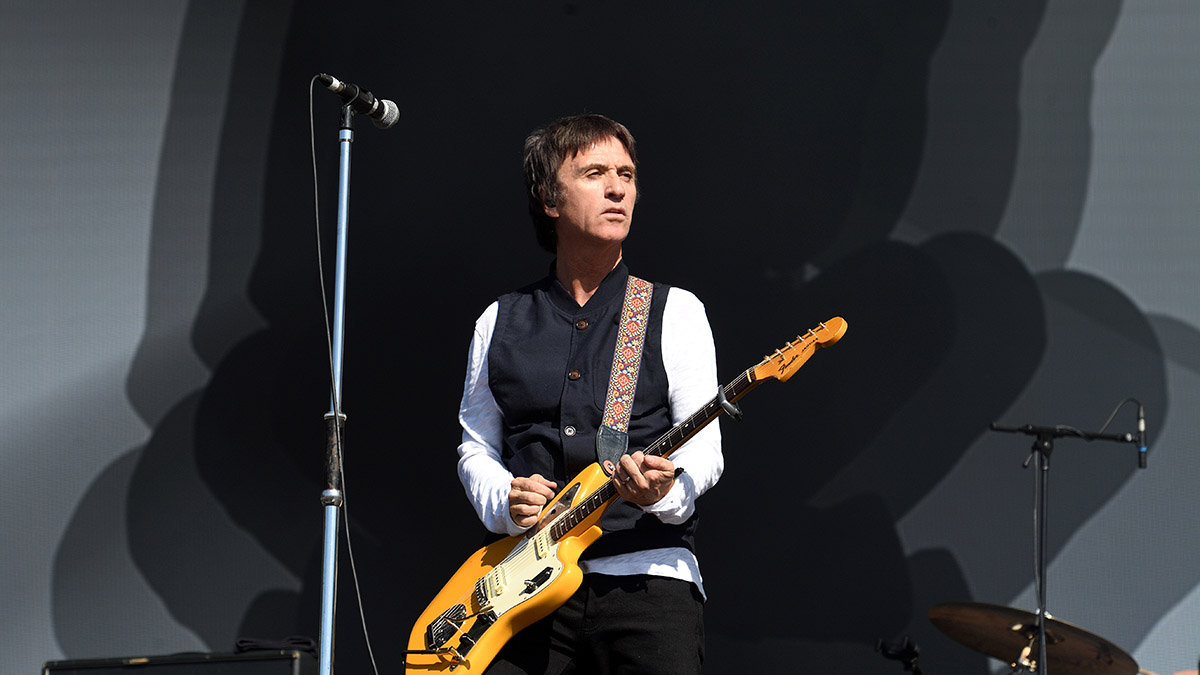

At 58, Marr still maintains the seemingly ageless mod hairdo he’s worn for years, and he boasts the kind of resume (the The, Electronic, Modest Mouse, the Cribs, and for a brief time, the Pretenders) that would make most guitarists green with envy.

As he eases oh-so-coolly into elder statesman status, he considers his legacy as a pioneering modern rock guitar hero: “I was never a shredder, but the term ‘guitar hero’ to me sounds actually quite noble. Back when I started, I wanted to be a guitar hero who played great songs. This was at a time when there were a lot of things being done on guitar that I felt were outdated and corny.

“But there was also a generation of young men in the U.K. and America who were onto something new – Robert Smith, John McKay, Will Sergeant. A lot of us took note from Richard Lloyd and Tom Verlaine. Those guys were game-changers. I loved all that… and still do.”

On the topic of game-changing guitarists, a lot of people would cite you and Peter Buck for how you both popularized the rhythm-lead style of playing in the early Eighties.

“Well, I wouldn’t disagree with that.”

While other players showboated their skills, you both seemed to operate with a kind of tasteful restraint.

“A big lesson I learned when I was very young – maybe 11 or 12 – was when I read an old interview with John Lennon. He was talking about serving the song and being a really good rhythm player. And then growing up in the Seventies, it seemed as if one of the Ten Commandments of Guitar was, “Thou shalt be like Keith Richards” – you know, be the engine of the band. There’s people like Mike Campbell, too.”

I remember that Lennon interview. He said, “I play rhythm. It’s an important job. I can make a band drive.”

“Exactly. There it is. Now, to be honest, I’m still not above fetishizing the guitar the way we all do. You get me with another guitar player, and we’ll trade our stories about the SG we got in 1980 or whatever. If there’s a room full of guitar players, I’m the last to leave, man. I’m just as hooked as everybody else, and I have been since I was 5 or 6.

My Jag sounds exactly like a Rickenbacker crossed with a Gretsch, but it plays like a Fender. It would’ve saved me quite a lot of money back in the day

“I just think that the way I looked at guitar playing was perhaps a little different from what others were at the time, and I think somebody like Peter Buck felt the same way. We both loved the look of Rickenbackers.

“In my case, it was actually to restrict me and force me to play a certain way, believe it or not. With a Rickenbacker, I had to focus on chords, which was the right thing to do. Peter and I have that in common. Over the years, we’ve become friends, and of course, he’s someone I’ve got great respect for.”

Not to belabor the Smiths, but does your time in that band now seem like a million miles away at this point?

“Oh, yeah. Without a doubt. I’ve never felt like I’ve been running away from it, but I left that band when I was 24. Any 24-year-old leaving any job wants to not be defined by that. I’m proud of the records the group made, but in all honesty, I’d say I feel like I’m probably on part four of my career now.”

After the Smiths, you’ve played with quite a few other bands. Do you go into these situations thinking they’re temporary, or do you sometimes think far beyond that?

I left the Smiths when I was 24. Any 24-year-old leaving any job wants to not be defined by that

“Actually, I go into each situation with no idea how it’s going to turn out, and that’s the exact same headspace as when I was 13, 14 or 15, when I would go around the neighborhood and play in different bands. The first major band I joined was called Sister Ray, and they were these really gnarly adults.

“I wanted to play with them because they sounded like a cross between the Stooges and Hawkwind, and I’d never played that sort of stuff. I thought, “Well, I’ll be a better guitar player if I learn to play at very high volume with these fairly druggy sort of reprobates who have a reputation for being amazing live.”

Sounds like a solid career move.

“Yeah. And then this other band that I joined had a really talented songwriter who lived just a few blocks away from me. It was a real challenge for me because he used to employ all these key changes and tunings. He was into Todd Rundgren and Andy Partridge, so we were playing all these passing chords. I got quite a lot of chops from that.

“Going into Modest Mouse, for example, was the grownup version of that. I was invited to go to Portland, Oregon, as a 10-day experiment, and what happened in that scenario was we got tight as pals very quickly. It was like a brotherhood, and then it was just too fucking weird to bail.”

Did the same thing happen with the Cribs?

“Very similar situation. We were supposed to cut four songs for a seven-inch or a 45 EP. I went in with all these riffs, and we just kept writing. The inspiration was flowing, so we went, ‘Let’s make an album out of this.’ From that experience, we formed a very strong friendship. So it’s actually the opposite of what it may appear to be on the outside. If you ask people I’ve been in a band with, they’ll tell you that I get very committed.”

Why then don’t you tend to stick around longer?

“I was in Modest Mouse for four years, and I was in the Cribs for three years. In each case, pretty much, I was ready to make another album, and the other guys weren’t. So I’d just go somewhere else and make an album.”

Let’s touch on some songs on your new record. Tracks like Receiver, All These Days and a few others have guitar sounds that hark back to the early days of the Cure and U2, but they also recall the early days of… Johnny Marr. Do you hear that?

On Ariel or on Receiver, there’s a real kind of flange thing going on, which is very much of my generation. And you know what? The part sounded great because of it

“Yeah, that was a conscious thing. I like those sounds. OK, I really have to put a kind of a modest disclaimer here: Along with some other people, I’m one of the reasons why those sounds exist. I like them, so I use them. On the other hand, it’s not like I haven’t gone out of my way to do other shit.

“For example, on the song Ariel, or on Receiver, as you mentioned, there’s a real kind of flange thing going on, which is very much of my generation. And you know what? The part sounded great because of it.

“On Ariel, when I played the main riff, I thought, ‘This is either me or Will Sergeant – or it’s both of us together.’ Those sounds were the vocabulary I used in the Eighties. They were useful then, and they still hit the spot when required.”

Tenement Time is drenched in delay sounds that collide off each other. And in Speed of Love, you play a heavily delayed solo that sounds as if you’re using an E-Bow.

“That’s me playing one of my Jaguars that’s customized with Fernandes Sustainer pickups. The guitar becomes a six-string E-Bow. Those pickups are amazing. If you’ve got the guitar on low, you can feel all the strings vibrate while you play. It’s beautiful, like an electrical storm all through the track.”

Are you using that on the solos in Human?

“The first solo break has the sustainer on, but the end solo is a 12-string SG, which is pretty rare. I’ve got it going through a Leslie. If anyone can be bothered getting that together, I really recommend it for the sound.”

In many ways, the album is like an instructional course on the many ways a guitarist can use delay and reverb pedals. As it is with the Edge, those sounds are a real part of your approach to composition.

“I just assume that delay is going to be part of the equation. I didn’t realize how much delay I’d grown into using until in the early 2000s, when a friend of mine picked up one of my guitars in the rehearsal room and started to play. And I thought, ‘Shit, man. There’s so much delay on there.’

People are usually quite surprised how much delay I’m dialing in at first, but it usually kind of disappears behind what I’m doing because I’m quite a busy player

“Around about the same time, Neil Finn pointed out to me that I play very loud yet gently. I never knew I played loud, because it doesn’t sound loud to me. My amps are very hot, but they’re also clean. As far as delay, I think I differ from somebody like the Edge, where it’s almost a mirror of what he’s doing. I play to it, so it’s just this halo.

“If you took it away, you would really notice. But while you’re listening to it – well, maybe you would notice, but a lot of people don’t realize just how much is on there. When I do sessions, which I still do, people are usually quite surprised how much delay I’m dialing in at first, but it usually kind of disappears behind what I’m doing because I’m quite a busy player.

You mentioned your Jaguar. Was that your main guitar on this record?

“Yeah. Over the years, I’ve kind of honed things down. The Jag does a big job. In short, my Jag sounds exactly like a Rickenbacker crossed with a Gretsch, but it plays like a Fender. It would’ve saved me quite a lot of money back in the day. I use that, but I always use a Gibson, as well. These days, I use ’73 Les Paul Customs for that dark thing.

“For the last seven or eight years, I’ve also played Yamaha SGs for their articulation. The guitar I’ve recorded with more than any of the guitar is the red Les Paul Standard that I got in 1985 when the Smiths did Meat Is Murder. If I’m ever doubling arpeggios, that’s my go-to clean arpeggio guitar.

I started using the EDS-1275, and I realized that it’s the best goddamn electric 12-string sound

“A while ago I started to use a Gibson doubleneck. Now I’m never without one because it’s just the best 12-string sound. It started with the movie Inception. It would be 3:30 in the morning, and I’d be jet-lagged and driving engineers mad while we were making a movie about people putting themselves to sleep. I realized the sound I was chasing was this distorted harmonic 12-string. And the only one that was in the building belonged to another composer.

“It was this funky old EDS-1275. I started using it, and I realized that it’s the best goddamn electric 12-string sound. For a start, you’ve got the old humbuckers on there, but then you’ve also got this massive wood.

“That gives you the option of letting the other neck ring out if you want to put it in a drone, which I sometimes do. That’s why I’ve recently acquired this very rare SG 12-string, because moving the other one around London, it’s like carrying a friggin’ sideboard.”

Any other guitars?

“I use a few acoustics that I’ve been using forever – Martins. There’s this company in the U.K. called Auden that makes these beautiful 12-strings, all handmade. So that’s it then – my Jags, some with the sustainer and my regular Jags, and then all the other ones. I try to keep things honed down.”

- Fever Dreams Pts 1-4 is out now via BMG.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.