“We cobbled together the Everything I Do solo in 20 minutes. Mutt Lange said ‘Eh, not bad.’ And that was it… We had no clue”: Bryan Adams guitarist Keith Scott on being a low-profile multi-platinum guitar hero – and the hits no one saw coming

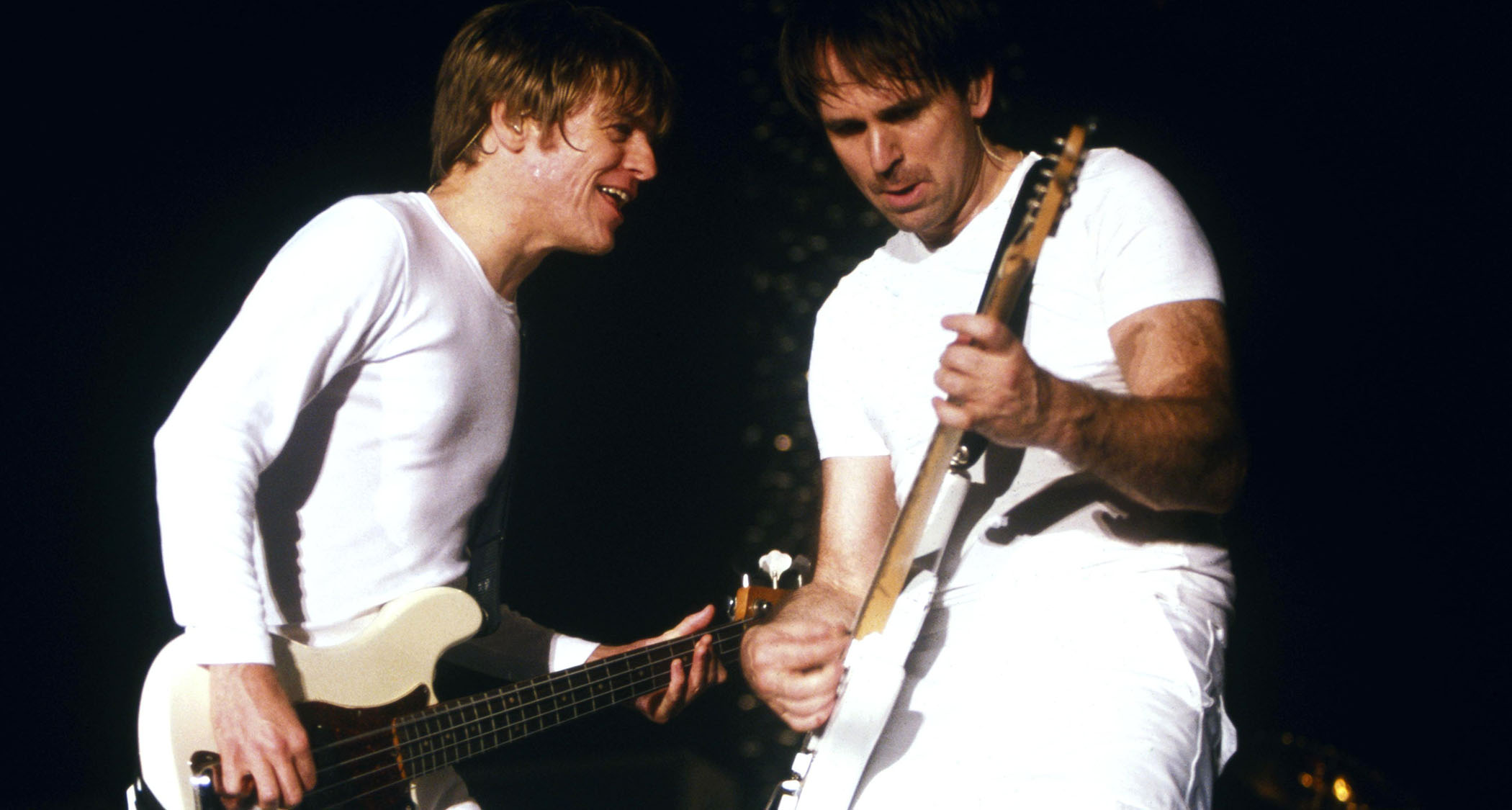

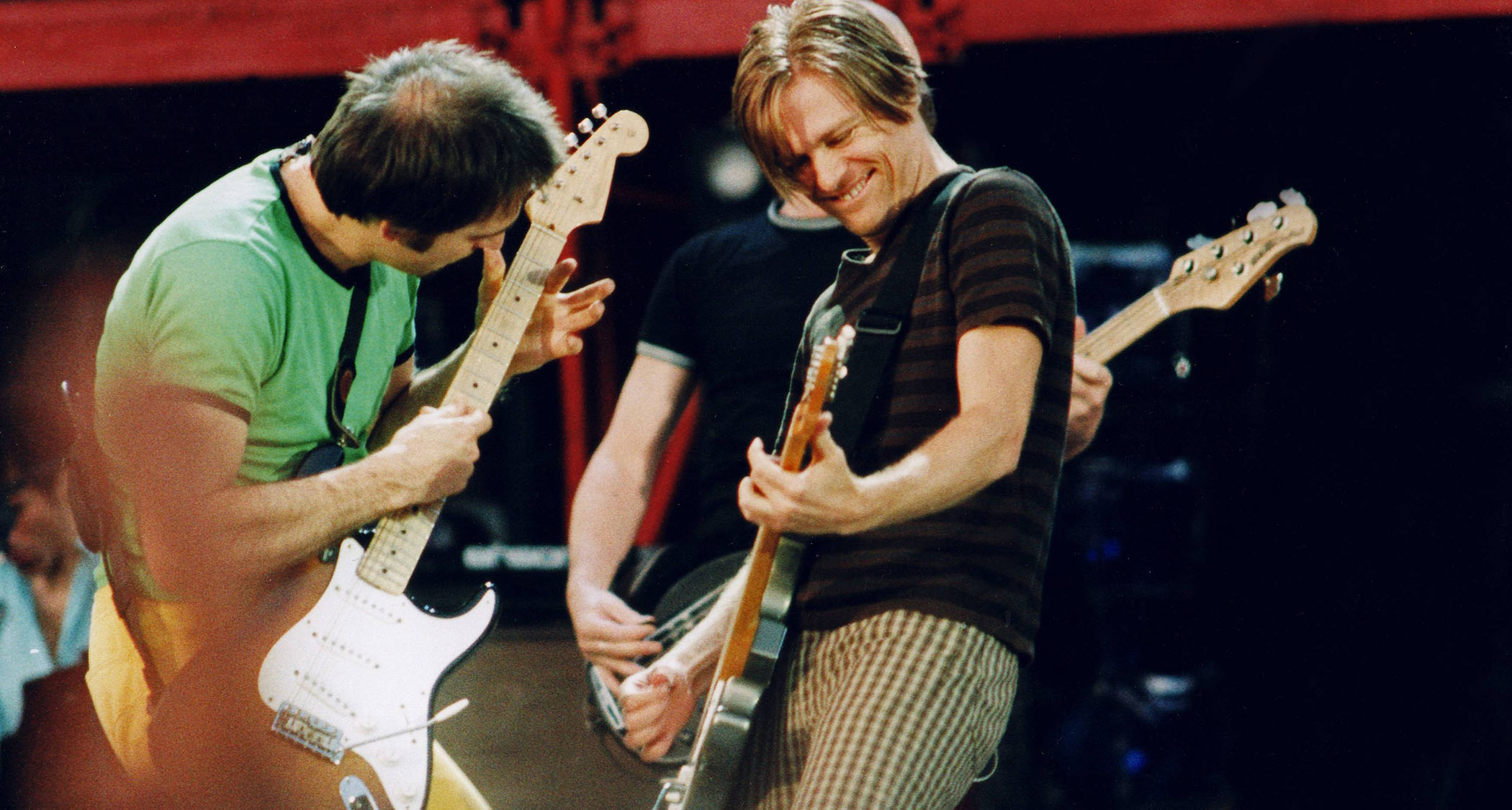

For more then 40 years, Keith Scott has served as Bryan Adams’ lead guitarist, which means he’s performed a cavalcade of ginormous smash hit songs – there’s Cuts Like a Knife, Run to You, Summer of ’69, It’s Only Love, (Everything I Do) I Do It for You, One Night Love Affair and tons more – thousands of times.

“I couldn’t guess at the actual number of times we’ve played some of those songs,” he says, then adds with a laugh, “It’s a lot, I know that.”

Even so, the Canadian-born picker maintains that each night on stage feels fresh. “It’s interesting. Back when I was playing clubs, we’d do cover songs,” he says. “After a while, I’d get bored playing the same songs over and over, and I’d want to move on. With Bryan, though, it’s different. For one thing, if a song is popular, the fans end up singing it, and that’s so exciting.

“But it’s also true that each night presents a new set of challenges. There’s always things you can’t control, so you always play your best, as if you’re performing a song for the first time. The songs deserve it, as do the fans.”

Scott’s vibrant playing style – a fiery, sophisticated blend of gritty blues and subtle jazz turns – has long been the secret sauce of Bryan Adams’ recipe for hits.

When each track called for a stand-out moment – whether short, head-turning bursts between passages or high-wattage, hook-filled solos that doubled as songs within songs – Scott came through with uncanny artfulness and dazzling showmanship.

Yet he remains something of an elusive figure to most music fans, and even among guitar circles his name is seldom mentioned. He’s the guitar hero nobody really knows.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“It’s never really bothered me,” he says. “I never felt under-appreciated. Put it this way: I know what it entails to become what we call a ‘guitar hero.’ I think you have to go out of your way to be that person, and it has to work for you.

“I never felt like I was that kind of artist. I’ve always supported singers, and I’m comfortable in that role. I like to play challenging things, but I never wanted to be the guy steering the ship. I enjoy being part of a team.”

Currently, Scott is ensconced in the position he relishes, performing with Adams on the singer’s So Happy It Hurts tour, a worldwide trek that’s scheduled deep into October (as of this writing). The two-hour-plus set is something of a retrospective victory lap, with every hit accounted for.

For Scott, 69, who is now beginning his fifth decade as Adams’ trusty guitar cohort, the opportunity to rock sold-out arenas isn’t one he takes for granted.

“I’m astounded that I’m still allowed to do this, especially at such a high level with Bryan,” he says. “It’s been such a strange and incredible journey, and I’m very grateful for all that’s come my way. Bryan and I share a similar idea in that we just want to do the work. We love the work. It’s really something special.”

You’ve always reminded me of George Harrison in that all of your solos are melodic and memorable. They’re not ponderous; every second seems to matter. Where does that come from?

“Funnily enough, before joining up with Bryan, I played a lot of fusion in clubs. Bryan would say to me, ‘Listen, you can’t do that doodly, doodly, doodly thing. You’ve got to think more around the vocal.’ He was always looking for the melodic thing, so it forced me to think more as a singer.

“Even on some of the demos from the early days, like Cuts Like a Knife, Bryan would put down his own guitar ideas – he’s a pretty accomplished guitar player – so I had something to work with as a guide.

“Sometimes I’d show up at songwriting sessions with Bryan and Jim Vallance [Adams’ longtime collaborator], and they’d just say, ‘Go!’ You’d hear things happening as you were playing and kind of fall into it, and hopefully your experience would help you through it.

“To this day, when I sit down with Bryan, I try to contribute something. I always ask him, ‘What are the words?’ If you get an idea and you at least get a sentiment from what he’s talking about, those are really good clues and guides for trying to come up with something.”

Throughout your years with Bryan, you’ve favored Stratocasters. Were you a Strat guy before you met him?

“Yeah, I had one before I was even performing. I found one for a couple of hundred dollars in the want ads in Vancouver. It was a ’60s model and it was kind of trashed, didn’t have a case. I saved up all my money one summer to get it. The first time you hold a really nice guitar, it’s so great. Then you take it apart and tweak it, set the floating bridge up and start emulating your heroes. I never let it go.

Did I think Bryan had a chance to make it? I don’t know, but I could sense his dynamic

“When I got hired at 18 for this club band, I was playing through a Marshall, but it wasn’t the right sound, so they kind of pushed me into a Gibson idea. I had an SG and then a Les Paul for a while – we were playing music that required a humbucking sound. But at some point, the next band I was in, I decided to go back to a Strat, and I never looked back.

“I still have the same Strat I bought off the wall at a retailer. In the early years with Bryan, I did a lot of recording and live shows with that guitar. I’ve had to retire it, but it’s still here.”

When you met Bryan, did you immediately sense, “This guy could make it”?

“Good question. At the time, I was in a really popular club act in Vancouver, and I was doing OK. I’d come out of a tough time when I wasn’t working, so I was feeling pretty confident. I had first met him a few years prior, and I thought he was an outgoing guy. He seemed driven. Did I think he had a chance to make it? I don’t know, but I could sense his dynamic.

“One night, he approached me in a club and said he’d just made an album called You Want It, You Got It. He said, ‘I need a band to go and promote it at the end of the year. Would you be interested?’ I thought, ‘OK…’ He gave me the record, which wasn’t so much what I was going for, but I thought, ‘Hey, you never know.’ Then things happened.

The challenge was to fit good ideas around everything Bryan did

“The band I was in started to move in a different direction, so I thought I should try the thing with Bryan for a while. We played this very famous club in Toronto called the El Mocambo, and Bryan’s management came up and said, ‘Hang on to this one because we’ve got all these people coming up from the United States. We could get a shot with this.’

“I was kind of given a cue to just stick it out. But I enjoyed the company. We still weren’t the band we were supposed to be. We had to change some members and get things where they had to go.”

Did it take a while for you and Bryan to click as guitar players? How did the two of you figure out your guitar duties?

“We were pretty democratic about it. I mean, he would have to play rhythm and sing, so that took us some things off the table for him. The key was trying to find parts. He did a lot of demos with his partner, Jim Vallance, who played guitar, too. I would have to try to find my voice. The challenge was to fit good ideas around everything Bryan did.”

I think he knew, when he asked me to become part of it, what I could do. It became more of a performing thing; you’re trying to create your own energy

Would Bryan give you direction at all, or did he just turn you loose?

“There was a little bit of all of that. He would say, ‘Now do your thing. You know what to do.’ I think he knew, when he asked me to become part of it, what I could do. It became more of a performing thing; you’re trying to create your own energy. This started around Cuts Like a Knife and Reckless, because we were able to go and support arena acts in the States in 1983.

“We were very fortunate to have gone on tour with Journey, and that was so big. Seeing the scale of everything and what kind of energy is required to get that many people excited in a big building, it had an impact on the songwriting. It became more direct, with more overdriven rock songs like Kids Wanna Rock.’”

In regard to performing, did it take a while for you to get your concert stage sea legs together?

“Oh, gosh, I’m still working on that one – 50 years later. You have to train yourself to look at people in the back and play to them, because your tendency is to look down at the faces in the first 20 rows. Most of the time, it’s dark and you can’t see past a certain point.”

The first big hit was Cuts Like a Knife. I read an interview with you in which you said you took numerous passes on that solo, but the keeper was done spontaneously.

“That’s sort of true. Bryan talks about that one. As time goes by, some of the details are a little skewed. I remember getting a demo cassette that isn’t far off from what I did, but the intro part of the solo, where I open with the trill and the bar pulls down, that just happened.

“Bryan liked it and said, ‘Oh, start it with that.’ Then something happened and Bob Clearmountain, the producer, had to take a call. He left and Bryan said, “Go for it.” He pushed the button and we just went – and we got a pretty good take. I think that’s what I remember.”

Reckless had hit after hit after hit – six of them. When you guys were listening to playbacks, where you all like, “Fuckin’ A, man, we got it”?

“No. [Laughs] You don’t know. Nobody knows. I mean, you have ideas – ‘Oh, this might work in a show.’ That’s kind of what you’re thinking and working for. ‘We need these kinds of songs because the crowd’s leaving after four songs,’ or whatever. There’s been so many cases in Bryan’s situation where a song had a life of its own.

“Summer of ’69 was put way in the back of the album, and to this day it’s one of our strongest crowd pleasers. But at that time, we never would have thought in a million years that song had that kind of life.”

That’s so funny. You would think that you guys were saying, “Oh, these are definitely hits.”

“Here’s another one: We were doing Waking Up the Neighbours [1991] with Mutt Lange in London. All that stuff was so guitar driven with big backbeat drums. At the end of the sessions, Bryan said that we had to do a song for a movie, and we had a deadline – we had to get it out.”

You’re talking about (Everything I Do) I Do It for You.

“Yeah. It literally got thrown together, which is saying something because we’d been working with Mutt for almost a year. We had a cassette of the great [film composer] Michael Kamen humming, playing along on a clavinet thing for about 30 seconds. That was that. Mutt said, ‘I think there’s a melody there.’

The record label hated Everything I Do... I believe Jerry Moss from A&M said, ‘Bryan, if you put this on your record, your career will be over’

“We broke for the weekend, came back, and Mutt came up with this bridge. By the middle of the week we had the track all programmed and everything with keyboards. The guitars came together in about a day – we cobbled together the solo in 20 minutes. I heard the changes go by – just simple F to C – and I thought, ‘This is my David Gilmour moment.’

“Mutt pushed the button, I did a couple of things, and then he said, ‘I like the first part.’ Then he sang me something, so I did that. Then Bryan did something and I did something else. Within 20 minutes, between the three of us, it was kind of done. Mutt said ‘Eh, not bad.’ And that was it.

“The record label hated it. I believe Jerry Moss from A&M said, ‘Bryan, if you put this on your record, your career will be over.’ The movie company didn’t have any other entrants, so they used the song. They were so embarrassed by it, so it played after the credits. And then all this magic happened, and the song became a hit. We had no clue. We’d shrug our shoulders – ‘Well, we don’t know.’”

I mentioned how economical your solos are, but on “It’s Only Love,” you pretty much played your ass off throughout the entire song.

“[Laughs] Yeah. That was one of those things where Bryan knew it was going to be a duet. We had already demoed it when he got Tina Turner to agree to it. I listened to the demo last year.

“I found the cassette and was so curious about it. It’s pretty close to what I did in the studio, except I used a Rockman on the demo. Once we got to the Power Station, we used the original as kind of a template, but we dialed up a mightier sound with a bigger amp.”

I asked you about Strats. Do you favor those models because Bryan tends to play big, hollowbody electric guitars?

“Yeah, I stay away from those hollowbodies because he’s kind of covering that. We try to complement each other. He loves the woody sound of those guitars – it works with his singing. In the beginning years, he used a Les Paul, like a Norlin-era one, and it was fine.

“He was using Gretsch for a little while – he had these anniversary models – and then he found the Gibson ES-295 and was like, ‘OK, I love this. This is just right.’ It’s got a bit of a smaller body, and it’s easier to manage. He’s been on that ever since.”

Between Live Aid and all the huge tours and events you’ve done over the years, have you ever gotten starstruck when meeting your heroes?

I don’t think so – I mean, not now. There’s always this thing in the back of my head when I meet somebody I admire – that they might disappoint me – you know, ‘Oh, that guy’s a jerk.’ Then the music will never be the same. In the beginning, I got to meet people and it was fun.

“Over time, I got to see how incredible a lot of these people are. As far as the things that make you star-struck, it’s not so much the art as it is how these people are as human beings. I look for that. If somebody is contributing in a way to make the world a better place, not just through music but in what they say and do, that’s what catches my eye.”

- Classic is out now via BMG.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.