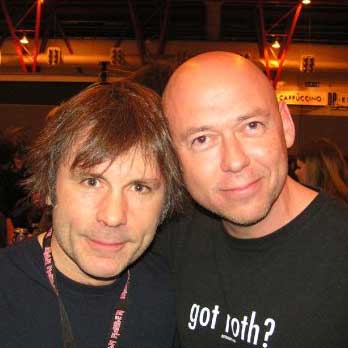

Mick Jones looks back at producing Van Halen's landmark 5150: "It was a pretty intense experience – but we achieved something very special"

The album's co-producer and Foreigner guitarist on the genius of Eddie Van Halen and a crazy, funky recording session

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

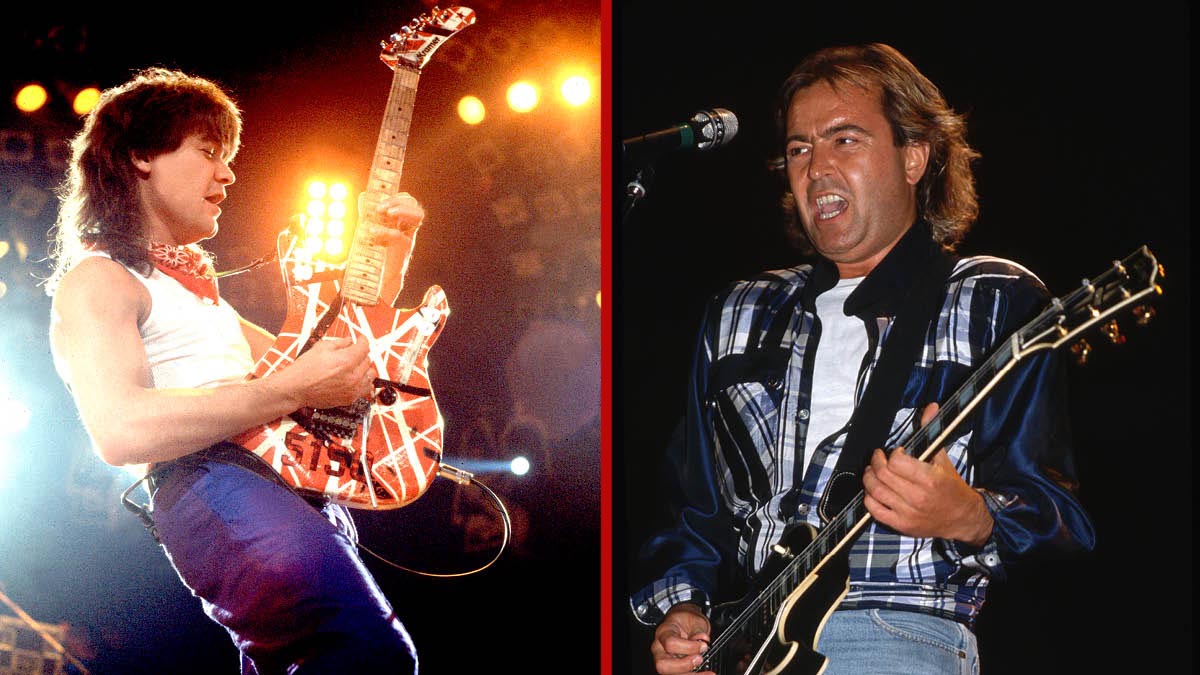

In 1985, when Van Halen singer David Lee Roth quit the band, Eddie Van Halen was left facing the toughest challenge of his career.

He was the most famous guitar player on the planet – the guy who had revolutionized the art of rock guitar in the late-'70s, and had got the call from Michael Jackson to play the solo on his mega-hit Beat It from Thriller, the biggest-selling album of all time. But with Diamond Dave gone, Eddie had to replace the seemingly irreplaceable, and reinvent the band that had defined American hard rock in the early '80s.

For all Eddie’s brilliance as a guitarist, Roth had been his equal in Van Halen – a frontman whose good looks and larger-than-life persona were instrumental in elevating the band to superstar status. In 1983, they had headlined the US Festival in San Bernadino, California before an audience of 375,000, and pocketed a reported $1 million in the process. The following year, their single Jump topped the US chart and its parent album, 1984, was well on its way to selling 10 million copies.

When the news of Roth’s departure was announced – on April 1st, of all days – there were many, fans and media alike, who believed that the band was finished. But by the summer, Van Halen had found a new singer in Sammy Hagar, a successful solo artist who had first come to prominence in Montrose, a band whose debut album, released in 1973, had a profound influence on Eddie, and was produced by Ted Templeman, who worked on every Van Halen album from 1978 to 1984.

Hagar proved a perfect fit for Van Halen. As a big hitter in his own right, he had more than enough self-assurance to replace Roth, and most importantly, as a singer, he had a better range and a more melodic sensibility.

As Eddie told Rolling Stone: “From the first second, Sammy could do anything I threw at him. It just opened up a whole new door.”

As a result, a new Van Halen was born on the album 5150, named after Eddie’s studio at his home in LA’s Coldwater Canyon (‘5150’ was the Californian law code for detention of mentally ill persons). And for Eddie, this album marked a major turning point.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Along with the new voice in Van Halen came a new approach to guitar – different tones, different gear. Out was the pinpoint positioned mixing style of old and in came huge stereo-panned rhythm guitars courtesy of an Eventide H3000. And while his trusty Frankenstein guitar and Marshall amps still saw studio action, Eddie was trying out a new six-string: the active EMG-loaded Steinberger GL-2T (in Stripe finish, naturally!), which would appear on Get Up and Summer Nights.

In the wake of Jump, the first Van Halen song for which Eddie, a classically trained pianist, played the main riff on synthesizer, 5150 featured even greater emphasis on keyboards. And in the creation of what was a game-changing album for Van Halen, and for Eddie in particular, another famous guitarist played a pivotal role.

Englishman Mick Jones, the leader of multi-million selling rock act Foreigner, was enlisted as co-producer on 5150. He had written all of Foreigner’s hit songs, from riff-driven anthems such as Urgent and Hot Blooded to power ballads including the worldwide number one I Want To Know What Love Is.

He had produced, or co-produced, all of the band’s albums. And he was a mean guitarist, as illustrated most powerfully in Juke Box Hero, one of the all-time great rock songs.

Long before he formed Foreigner, Jones had also toured in the late-'60s as the guitarist for French star Johnny Hallyday, with The Jimi Hendrix Experience as the opening act. And as he now tells Total Guitar, when looking back on the making of 5150, what he heard in Eddie Van Halen was genius comparable not only to Hendrix but to Bach and Beethoven...

Firstly, how did you get the job of co-producing Van Halen?

"It came through Sammy Hagar. He and I went back a long way, and we had maintained a friendship over the years. I’d also met Eddie socially several times, but it was Sammy who put my name forward, and then Eddie decided he’d like to work with me."

You were brought in because the band’s regular producer, Ted Templeman, had defected to work on David Lee Roth’s solo album Eat ’Em And Smile. But Templeman’s right-hand man, engineer Donn Landee, remained loyal to Van Halen.

"Yes, Donn had engineered all of their albums up to 5150, so I was the new boy. There was some concern from Donn, and that took a little bit of... Massaging, let’s say. But it all worked out, and by the end of the recording we were the best of friends. Donn is a great engineer and it was an honour to work with him."

At the time I was taking a break from Foreigner and I wanted to branch out a bit. So with Van Halen, it was a new challenge to see what I could pull out of them and see if I could change a few things

How did you see your role as co-producer?

"At the time I was taking a break from Foreigner and I wanted to branch out a bit. So with Van Halen, it was a new challenge to see what I could pull out of them and see if I could change a few things here and there. Not to mess with their identity by any means, but just try to enhance the sound and the arrangements..."

What do you remember about your first day working with them?

"Sammy picked me up from the airport and he gave me a rundown of what to expect. It was a little scary! He said, ‘Mick, we’ve been through the wars – this goes a little bit higher and a little crazier. So buckle your seatbelt!’

"But when we arrived at Eddie’s place, all of the guys were very cordial, very chatty and ‘up’ and cracking David Lee Roth jokes. So it was a nice warm welcome. And I was a little nervous, but I think that tends to bring out the best in me."

The studio – in a converted garage, and designed by Donn Landee – was the band’s HQ and Eddie’s man-cave. Can you describe what you found in there?

"It was definitely funky. Everybody was smoking like crazy and drinking this high-alcohol content beer. Luckily I didn’t really drink beer, so I avoided that. So yeah, it had a vibe. It wasn’t the cleanest or most hygienic place I’ve ever spent time in, but it was acoustically designed and they had developed the sound in there. It definitely had a sound."

What tracks did they have ready at that stage?

"They had demos of all the tracks that made the final cut, pretty much. The only one that wasn’t demoed was Dreams, and I would say that was the one I had most involvement with from an arranging point of view. I think I really brought something to that song, especially Sammy’s vocals.

"I worked very long and hard with him on that, and he told me it was one of his all-time favourite performances. He was singing so high that he was hyperventilating. He almost passed out! I really pushed him. But we got it."

Sammy was singing so high that he was hyperventilating. He almost passed out! I really pushed him. But we got it

With Dreams and other songs such as Love Walks In, Eddie played the riffs on synthesizers...

"He developed his own style of keyboard synth stuff . It was a slightly different direction, but it was still rock. It really felt good when I first heard the songs. And they made it pretty easy for me. They gave me a great drawing board. Gradually as we got to know each other, things really gelled."

Eddie was also experimenting with different guitars.

"Of course he was playing that famous red Strat with the cream gaffer tape around it, but also a Steinberger. I used a Steinberger for a while at that time."

Did you hear this as Eddie reaching for something beyond the classic Van Halen ‘brown sound’?

"I didn’t really dissect what it sounded like. I just knew that it was powerful. And I felt that we captured the spirit of what was going on. I think they really wanted to show David Lee Roth that he wasn’t indispensable – let’s put it that way."

Certainly there was a different tone in Get Up, a really fast and furious track.

"I’d never heard anything like it in my life. It sounded like four guys fighting inside the speaker cabinets, beating the shit out of each other!"

They really wanted to show David Lee Roth that he wasn’t indispensable – let’s put it that way

Presumably you didn’t feel the need to coach him as one guitar player to another?

"He was so talented, so there wasn’t a lot I could add or suggest from a performance point of view. And he had a unique style, obviously. I didn’t want to say things for the sake of it. I thought seriously about what I was saying, what I was contributing."

But he would look to you for approval, for feedback?

"Yeah. I think he respected my songwriting – he knew I could write songs, and that was a plus for me. Some of the songs needed a bit of tailoring, and I think I provided that, as well as feedback. I wasn’t afraid to speak up about how I felt, which was a little risky, I guess."

It seems strange to ask, but were there moments when you said, ‘Sorry Edward, that I don’t think that solo is good enough’?

"There were several times that happened – and then I would sprint out of the door and run into the forest at the back of the studio! But I think we respected each other, and we both had the experience to be able to sensibly exchange opinions."

Eddie was completely out there – he just went into this trance state as he played. I’d be sitting there on the left side of the console and he would come over and lean on me while he was playing

So you and Eddie had a strong connection?

"We got very close, especially when we were doing guitar overdubs and solos. He was completely out there – not drug-wise, he just went into this trance state as he played. I’d be sitting there on the left side of the console and he would come over and lean on me while he was playing. And it was kind of weird – it was like it was coming through me. It was coming down, let’s say, from above, and we really got very close in those moments."

Did you and Eddie find time to jam together?

"Yeah. We had a few fun moments. Eddie tried to teach me the tapping thing. It was a hilarious hour or two."

There wasn’t any tapping on subsequent Foreigner albums.

"No. I didn’t latch on to that at all."

Brian May told TG that when he and Eddie worked together on the Star Fleet Project album, he had some fun playing Eddie’s Frankenstein Strat. Did you?

"Yeah, but I remember the fretboard was quite wide, and I haven’t got really big hands, so I had a little difficulty covering the size."

What was Eddie like as a person?

"Eddie had an irresistible grin, almost constantly when we were working, and outside the studio, too."

Did you feel that this was a musician completely dedicated to his art?

"Yes, he was a very musical person, always picking up new things, and very aware of the art of it all. You could compare him perhaps to Bach, Beethoven – uncannily talented and driven by a need to express himself in a dazzling way. So he was a complete musician."

And as someone who witnessed Jimi Hendrix performing at his peak, did you view Eddie as a genius comparable to Jimi?

"Yes, I think there are some individuals that are kind of chosen to be the carriers of the feeling and the spiritual side of things. I’ve always tried to fathom where and how that comes through. It happens with guitar players, it happens with singers... It does separate people. It separates the men from the boys. It’s a gift. And it’s such a powerful gift that sometimes it destroys the messenger. But I remember them both as very sweet guys, so charming, radiant and so super-talented."

The making of 5150 took a lot out of Mick Jones. “I was completely exhausted at the end of it,” he says. “We were running a bit late – and the band had a tour booked. So there was pressure.” But in the end, the album proved a huge success.

Released on March 24th, 1986, 5150 was the band’s first US number one album. And that victory tasted even sweeter when David Lee Roth’s Eat ’Em And Smile, featuring rising star Steve Vai on guitar, only made it to number four.

5150 turned out to be one of the most important albums Van Halen ever made. And Mick Jones is proud to have played a part in it. “It was a pretty intense experience,” he says. “But we achieved something very special.”

Content Editor at Total Guitar and freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2005, Paul Elliott has worked for leading music titles since 1985, including Sounds, Kerrang!, MOJO and Q. He is the author of several books including the first biography of Guns N’ Roses and autobiography of bodyguard-to-the-stars Danny Francis, and has written liner notes for classic album reissues by artists such as Def Leppard, Thin Lizzy and Kiss. He lives in Bath, UK – of which David Coverdale recently said, “How very Roman of you!”