Rush's Geddy Lee: how we made Clockwork Angels

A deep dive into the bass behind Rush’s spellbinding final release, Clockwork Angels

Spontaneous-sounding and song-friendly, yet grand in scope, Rush’s spellbinding new release, Clockwork Angels, follows the adventures of a young man across a steampunk landscape filled with alchemists, anarchists, buccaneers, sorcerers, carnivals, and lost cities.

For prog rock’s quintessential trio (bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee, drummer Neil Peart, and guitarist Alex Lifeson) the creation of the album was a journey in itself. Started in 2008, only four songs had been written by the time Rush launched the wildly successful Time Machine tour in 2010, which led to another go-round in 2011.

Travels and distractions not withstanding, ultimately two events brought the 12-track concept disc to fruition: Peart’s steampunk vision, for which he huddled with best-selling science fiction author Kevin J. Anderson, and a series of intense jams between Lee and Lifeson.

Typically, Geddy Lee has served as the glue of Rush, pulling together Peart’s lyrics, Lifeson’s sonic canvases, and jam highlights with his own melodies, arrangements, and orchestrations. It’s the same role he plays on the finished recording, where his vocals - deeper in tone but also in meaning these days - center the songs, and his inimitable barking bass moves effortlessly and willingly from shadows to light.

We talked to Geddy in London, amid an unrelenting avalanche of international press interviews, where time slowed down as our discussion of Clockwork Angels took a decidedly bass slant.

What set Clockwork Angels in motion, and what was your concept?

We felt like we needed to have something contemporary when we tour. We hadn’t had anything new in three years when we launched the Time Machine tour, but we had at least started writing Clockwork and were able to include two of the songs on that tour [“Caravan” and “BU2B”]. As for the vision, I think we were ready to stretch out a bit and try something fresh. We fell in love with the whole steampunk aesthetic; it really suited the kind of vibe we’re into. We were up for attacking a different kind of storyline, but we wanted to be sure not to do it in the same way as in the past, with 2112 and Hemispheres, where the same musical themes ran through most of the songs. Here, we wanted these to be distinct songs that would stand up on their own, whether part of or detached from the story. So musically and lyrically, they had to be quite clear and independent, yet related to carrying on the single-story theme of the album.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You and Alex did a lot of jamming for this record. How much of the music was derived in this improvisational way?

We worked in a few different ways. Some of the longer songs, like “Headlong Flight,” “Seven Cities of Gold,” and even “Carnage” were born out of jams. Other songs, like “Caravan,” “BU2B,” “The Wreckers,” and “The Garden” were written to lyrics with the intent of structuring them around the story of the song itself. With regard to improvisation, we tried to remember the spirit and vibe of the inspirational jamming moments and apply and retain it throughout the recording process. Even though we record our parts separately, and my parts are mostly worked out, our mindset was to keep that feeling of spontaneity—to feel like our playing was being pushed to the edge, beyond what is safe. That allowed us to almost get lost in the songs. It’s a bit of flying blind, but it’s exciting and encouraged us to explore our own playing.

When you were creating and recording your bass lines, how much did you take into account that you’ll have to sing and play them live?

Not at all; I never worry about it at that point. I write whatever part is going to serve the song best, and when we start rehearsing for the upcoming tour I figure it out and learn to do both at the same time, as well as how to create and trigger sounds I need on the keyboards.

The title track has an interesting new sound and feel for the band.

That song began with an experimental instrumental soundscape Alex wrote using technology, resulting in some amazing textures. When the lyrics came along, I saw a way to break down what Alex had into several sections and write some melodies over the top, and before long we had created this interesting rock/electronica song. The trick, both in recording and mixing, was to retain the spacey, mysterious sounds while keeping the song urgent and somewhat organic. Neil had that swingy, shuffly groove in mind when he first heard the demo, and when the song was finished we both couldn’t wait to tackle that feel.

“The Anarchist” is typical of Rush songs where your bass provides a key melody.

It was one of the more satisfying bass tracks, and it will probably be the most difficult for me to sing and play! The bassline drives the chorus and is an integral part of the song. When I put the chorus together, it was very much writing the bass melody and then writing the vocal melody to work around that bass melody. I recorded two bass tracks: the first down low and the second doubled an octave above, to give it that 8-string-bass vibe – but recording them separately allows you to control the tone much better than actually using an 8-string bass.

In general, my bass parts depend on what the song needs and how it comes together. There are some songs where the bass wants to be upfront and almost wants to pull away from the track. And there are other songs where it’s not about the bass, it’s about the bottom end, so I try to just provide a low end that feels satisfying with the drum part and doesn’t compete with anything else going on around it. However, being a trio, I do think it’s important that the personality of each of us as individuals is visible, regardless of the kind of part it is.

On songs like “Headlong Flight” and “Halo Effect,” your bass creates counter-lines to the riffs, vocal and solos. What’s your process there?

I’m trying to come up with melodies that work around what’s going on, to add a level of orchestration. I do that pretty much by ear as opposed to specifically following the harmony. “Headlong” is interesting; the opening main riff is a repeating figure throughout, but in different forms and time signatures. That’s how the song got going, out of this furious jam I had with Alex. I was jamming with him in the lower register, and he’d start riffing on my riff ; then I would move up the neck and he would go somewhere else. When we found that line, it seemed to be such a classic, circular riff , with so much propulsion to it. I knew when Neil got to sink his teeth into it, it would really start to move.

Let’s talk about the opening bass feature on “Seven Cities of Gold.”

[Laughs.] It’s sort of a retro white funk feel mixed with crazy, Robin Trower-y guitar licks [see music]. I’m plucking and hammering, while muting with my right hand. It feels like the opening to an old softcore porn movie! Part of it is stiff and not very funky, yet I’m trying to funk it up. It was a weird moment that we just liked and kept. I love the song – it has a nice tempo that you can kind of hold back on and play in a bluesy rock vibe.

How did you come up with the opening bass line on “The Garden”?

That’s me fingerpicking, like a classical nylon guitar; the part came to me while jamming with Alex [see music]. I like to play around with fingerpicked chordal pieces, but it’s rare to find a place for that in Rush, because it doesn’t cut through. “The Garden” is delicate enough that I could do it. The first time around I use a pure, clean tone, and when the part returns I add some amp sound for dimension. It’s the piece I’m probably the most proud of on the record. The lyric wraps the sentiment of the story of this person’s life, and it has a universal sensibility everyone can relate to. We wanted the vocals and the song to be heartfelt and relaxed, without being wussy or syrupy. That’s hard for a rock band that likes to pump it out – to play those gentler moments and make them feel authentic. I felt we accomplished it, though.

What basses did you use on the album, and how did you record them?

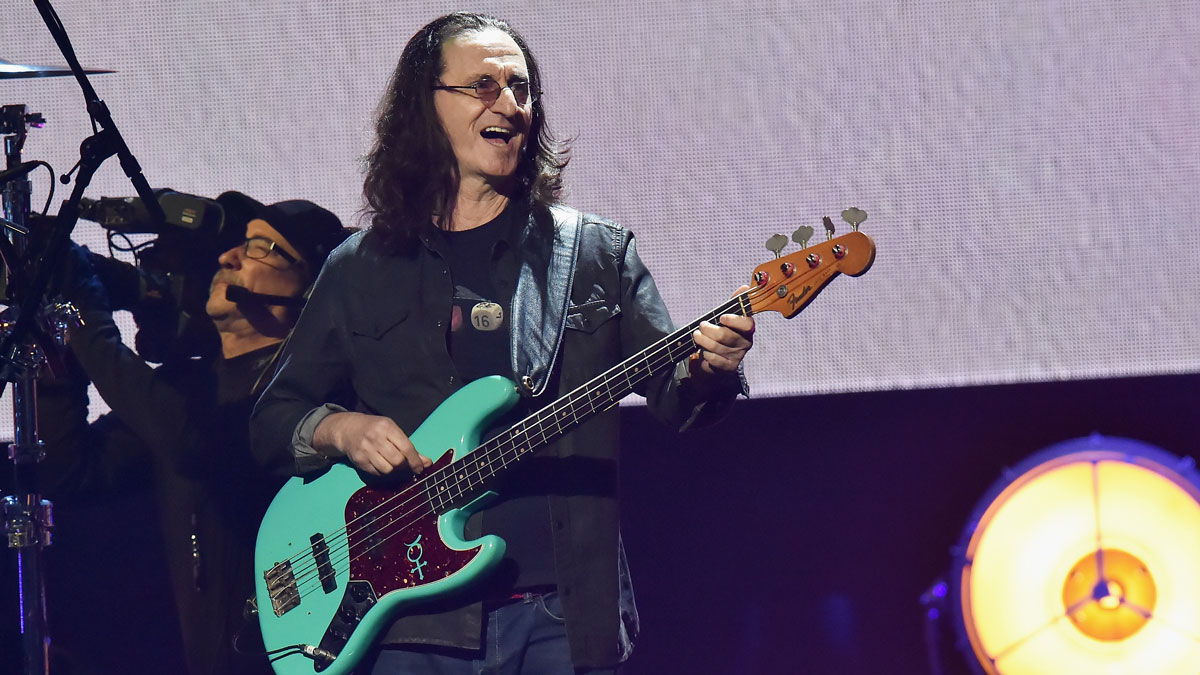

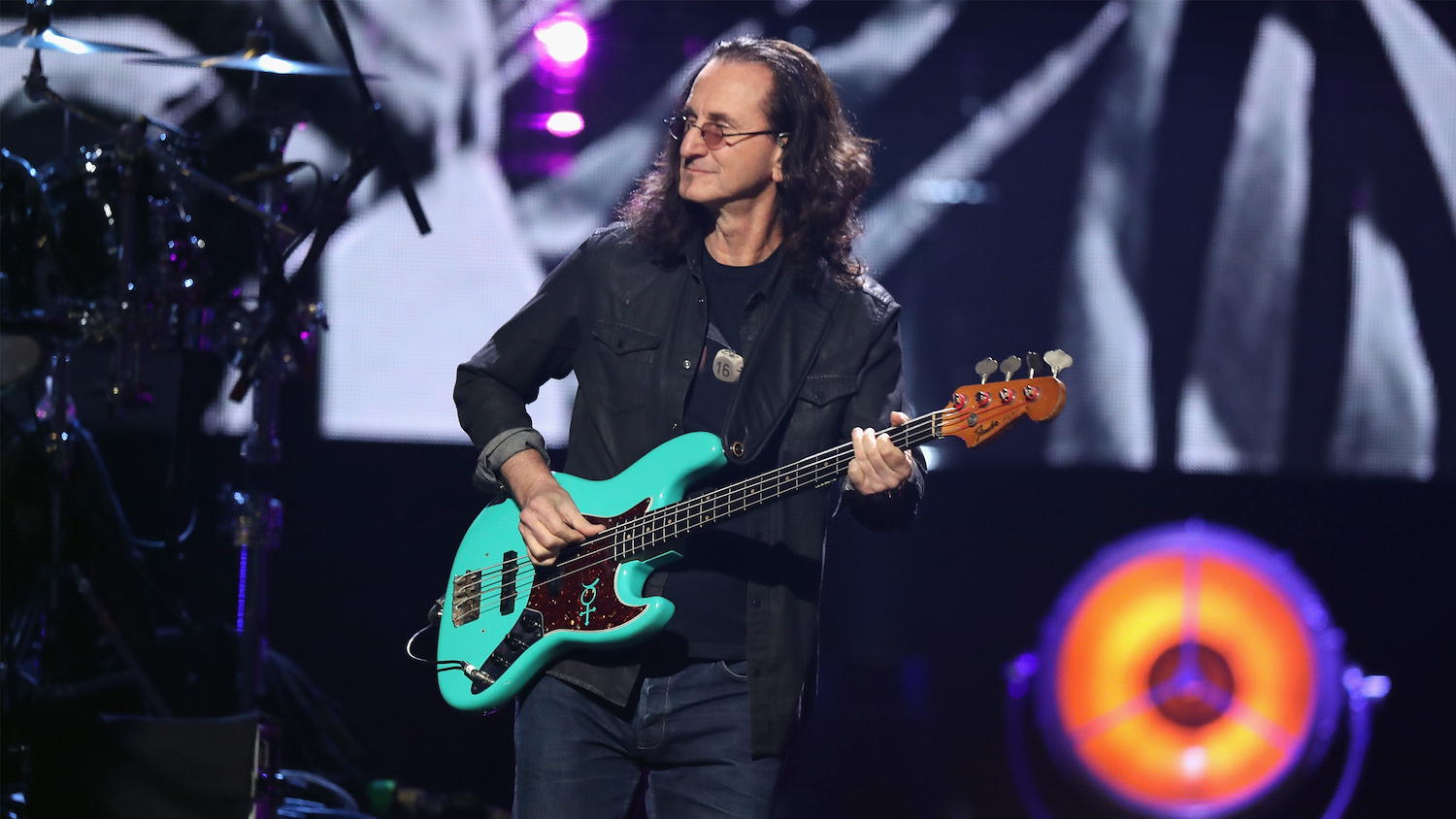

I played four Jazz Basses [see gear]. On most of the tracks I used my main black ’72. On “Seven Cities” and “Carnies” I used my sunburst ’72, which has a new Fender Custom Shop maple neck. I used my red Fender Custom Shop J-Bass on “Wreckers” and “The Garden”; it has a beautiful, round bottom and a cleaner top end, so I play that on the songs that need a bit more depth and aren’t quite so slamming. And I used one other J-Bass on “Wish Them Well,” that I can’t recall. I recorded the basses on four tracks: one went straight to the Avalon U5 DI; one went through my old ’90s Palmer PD1-05 Speaker Simulator, which adds presence to the lower mids and upper lows; one went through my Sans Amp RBI preamp, which gives me great distortion and crunch; and one went through my Orange rig. All four signals go through old tube compressors and are added in different amounts on different songs during the mix. There are also a couple of spots with some old school phasing via plug-ins.

With guitarist Alex Lifeson for the Time Machine tour, you returned to using live rigs onstage for the first time in a while. What was that like?

It was great; the stage crew hated it, but I liked it [laughs]. Wherever you went on stage left, the bass was yelling at you the whole time. Really, it’s all about what our front-of-house guy wants, so I defer. I don’t think I’ll have the working cabinets for the Clockwork tour; I have my in-ears and I can control my sound very accurately through them.

Also on the Time Machine tour, you played Moving Pictures in its entirety. How did that go, and did it require any special preparation?

That was a real highlight of the tour for me. I loved playing the whole album; I was amazed at how it still flowed after all these years, and I thought the material stood the test of time. I’m sure we’ll do something like that again. We’ve played a lot of the songs at various times, so nothing really kicked my butt; the basslines all came back pretty easily. The only song that took a bit of rehearsal was “The Camera Eye” because some of the parts are quite long, and then for some stupid reason we decided we wanted to trim off like a minute and a half of it – which actually made it more difficult to relearn!

What are the Clockwork tour plans, and your plans beyond that?

We’ll tour North America in the fall, take a break, and head to Europe and other global ports starting in spring 2013. Beyond that, who knows!

Geddy Lee Selected Discography

With Rush (on Roadrunner) Clockwork Angels [2012]; Time Machine 2011: Live in Cleveland [2011]; (on Atlantic) Snakes & Arrows [2007]; Feedback (EP) [2004]; Vapor Trails [2002]; Test for Echo [1996]; Counterpoints [1993]; Roll the Bones [1991]; Presto [1987]; (on Mercury) Hold Your Fire [1987]; Power Windows [1985]; Grace Under Pressure [1984]; Signals [1982]; Moving Pictures [1981]; Permanent Waves [1980]; Hemispheres [1978]; A Farewell to Kings [1977]; 2112 [1976]; Caress of Steel [1975]; Fly By Night [1975]; Rush [1974]. Solo albumMy Favorite Headache [Atlantic, 2000].

INSIDE GEDDY’S GEAR WITH HIS TECH JOHN “SKULLY” McINTOSH

Geddy’s Number One bass is a black ’72 Fender Jazz Bass, which has been in the fold for many years. This is the bass that has been seen time and time again, onstage and in photos, and to which all other bass guitars are compared. This instrument carries most of the weight during the show. The bass received a new Fender Custom Shop neck in 2010, just prior to the start of the Time Machine tour. This neck has a maple fingerboard with a 9” radius, white binding, aged pearl block inlays, and a little more mass than the typical Geddy Lee-style neck. The back of the neck has a rubbed oil finish, as do all the basses that go into the studio or out on tour. This is the third neck this bass has seen, and it is set very straight for an extremely low string height and fast action. The alder body is of medium weight, with an aged pearl pickguard custom-engraved by James Hogg with the now-familiar “Amalgamation” symbol. All the touring basses have scratch plates engraved and paint-filled by James with various alchemical symbols. The pickups are original, although the bridge pickup was rewound to virtually original specs by Tom Brantley in 2010. A BadAss II bridge, Dunlop strap locks, and leather guitar straps courtesy of Levy’s Leathers are standard issue on all the touring basses.

The Number Two bass is a sunburst ’72 Fender Jazz, and is perhaps closest of all the basses to Number One. It has a neck made in 2011 by Mike Bump of the Fender Custom Shop; it too has a maple fingerboard with a 9” radius, but black binding, and black block inlays. Number Two has a set of custom-made pickups by Tom Brantley. The black ’74 Jazz has a neck which is the twin of Number One, both being made at the same time in 2010. It has the original pickups, but with a little voodoo inside to get just a little something more out of them. All three of these basses have the original tuners and string trees installed on the new necks.

Next is a Fender Custom Shop Jazz Bass with an ash body, maple cap, and a Candy Apple Red finish. It has a slightly more slender neck, again with a 9”-radius maple fingerboard. This bass has been around for a while and has pickups from the Fender Custom Shop, in a ’60s-style spacing. There is a black Jazz Bass assembled from parts—with another neck from Mike and pickups from Tom—that could very well make an appearance this year, as well as some possible new surprises. All of the basses, regardless of their tuning, are strung with Rotosound Swing Bass RS 66LD strings (.045–.105).

On the Time Machine tour the bass signal came through a Shure UHF-R system which was switched via a Kitty Hawk MIDI Looper to an Axess Electronics splitter. From there, the signal went out in parallel to a SansAmp RPM preamp, Palmer PDI-05 speaker simulator, Avalon U5 DI, and an Orange AD200B MKIII amplifier, which in turn drove another Palmer PDI-05. A Rivera RockCrusher power attenuator provided a load for the Orange. These four lines then ran direct to the PA. In the studio, an Orange 4x10 cabinet was miked in place of the second Palmer and the RockCrusher, but on tour there will be no speaker cabinets in the bass rig. There are also no monitor cabinets onstage, save for the subs which augment the Logitech Ultimate Ear monitors worn by the band, and many of the crew.

On tour, this arrangement is supplemented by Brad Madix at front-of-house and Brent Carpenter on monitors, who each add a fifth channel of amp modeling done in the console. Other than the subtle changes that Brad or Brent might make during the course of the show, the bass rig is dialed in, and does not change from song to song. Instead, the variety of bass tones are determined by how Geddy plays the bass itself. The basic format of this rig is unlikely to alter drastically for this year’s Clockwork Angels tour, but you can never count out the possibility of a change or addition of a piece of gear. The bass rig is an ongoing evolution that will never cease.

All indications are that the “Gefilter” [a mock vintage time machine] will return to the stage. Its powers are immense and frightening. The two keyboards seen onstage are a Moog Little Phatty and a Roland Fantom X7. While the Roland produces the odd sound, its primary function is to control the bank of Roland XV-5080s that reside offstage right under the watchful care of Jack Secret. These samplers are also triggered by two sets of Korg MPK-130 pedals, one set of which resides below the keyboard rig, and the other at the main mic position.

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.