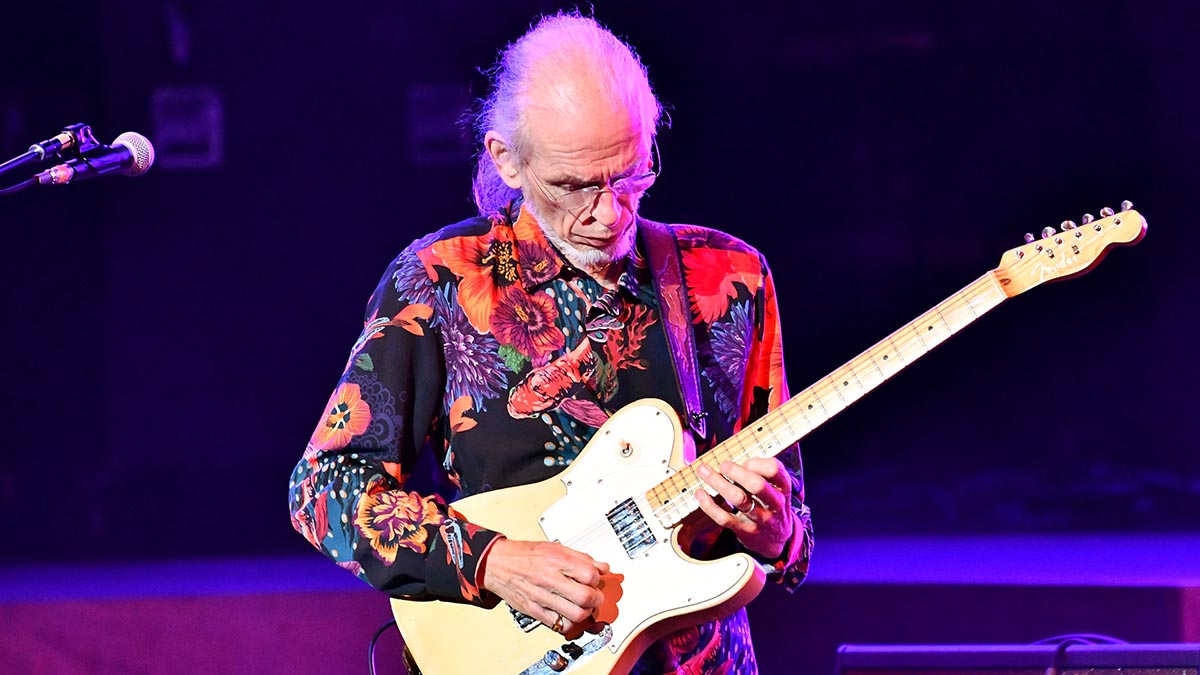

Steve Howe: “Sometimes I’ll play something and it’s over the top, so I’ll pull it back. There’s a certain kind of order and sensibility I like to bring to my guitar”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In and of itself, Yes’s new album, The Quest, is significant as it ends one of the longest gaps between studio recordings for the progressive-rock legends (the last time they released a studio effort was in 2014, with Heaven & Earth).

Guitarist Steve Howe acknowledges the fact that the band’s fans have been clamoring for new music, but he also defends the decision to hold off and not hurry.

“I’m not the guy who will say, ‘Let’s rush and make another record,’ because I’ve had my fingers rapped too many times with the outcome of that,” he says. “I’ve been disappointed with some of the recent albums Yes recorded, starting with [1997’s] Open Your Eyes.

“I mean, they all had their merits, but I think to make a really good album, you need the proper circumstances and atmosphere. Everybody has to feel really ready. So as far as the long gap, all I can say is, some things are worth waiting for, and I think this album is worth the wait.”

The Quest is notable in other ways. Not only is it the first Yes album on which founding bassist Chris Squire doesn’t appear (he passed away in 2015), but it’s also the first record to feature a lineup devoid of any original band members. Howe and drummer Alan White are now the two elder statesmen [Editor’s note: Howe replaced Peter Banks in 1970; White replaced Bill Bruford in 1972] in a group that consists of singer Jon Davison, bassist Billy Sherwood and keyboardist Geoff Downes.

“It’s certainly a different dynamic in the band these days,” Howe says. “In terms of Chris Squire, we obviously felt the loss, and we know the scale of what losing him means. But what we’re trying to do is not wallow in regret. When we tour, we pay tribute to Chris by playing his song Onward and showing pictures of him. The legacy of what he left us is immense.”

When we tour, we pay tribute to Chris by playing his song Onward and showing pictures of him. The legacy of what he left us is immense

The guitarist is effusive in singing the praises of Sherwood, who began an on-and-off association with Yes back in 1989 and continued through various incarnations of the group (including spin-off projects), sometimes serving as additional guitarist and keyboardist before assuming full-time bass duties following Squire’s passing.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Billy’s really done an amazing job,” Howe says. “As most people know, he was one of the biggest Chris Squire fans in the world. The two of them worked together in Yes and in other things for a long time, so if anybody was equipped to step into this role, it’s definitely Billy. Losing Chris left us in a difficult position, but Billy stepped up to the game. I can’t say enough about him.”

Clocking in at just over 60 minutes, The Quest is a sprawling work that recalls the sound of classic Yes – there’s heaping doses of Hammond organ and spiraling vocals – done up in a starkly modern and sometimes edgy way. It’s grand without seeming pompous, reverential without being dreary.

Even when the band employs a full orchestra on the sumptuous ballad Minus the Man or the progressive-rock thriller Dare to Know, there’s not a whiff of pretension – it’s theatrical, not showy.

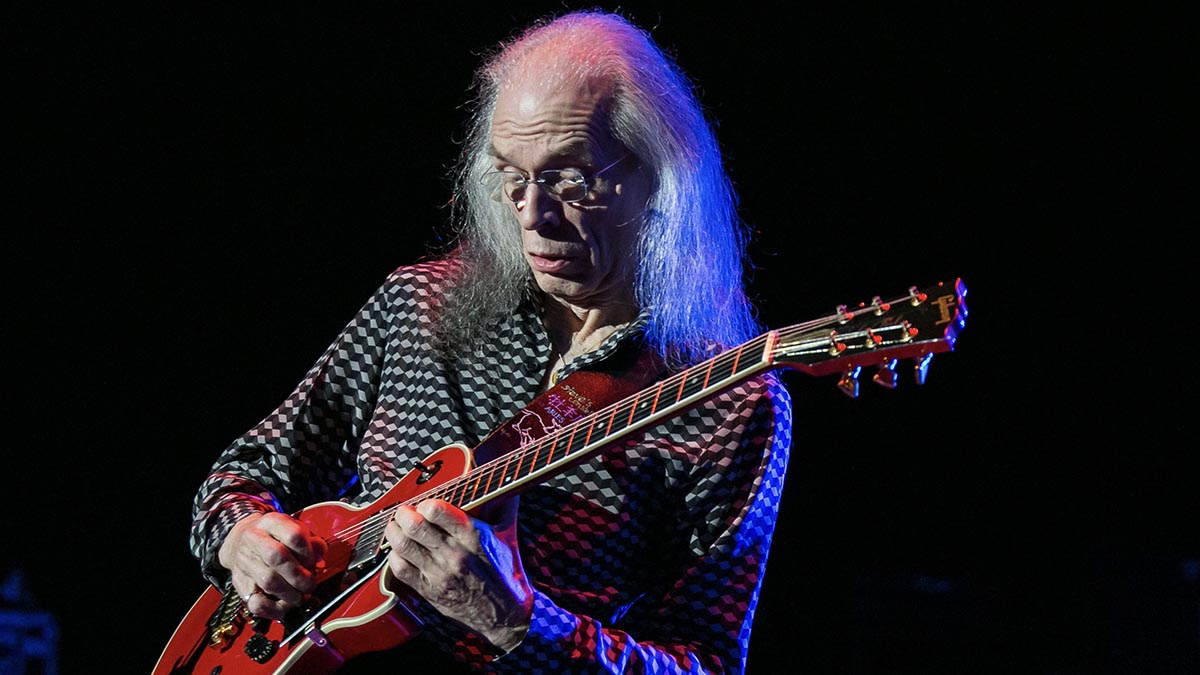

Throughout the album, but especially on the widescreen epic The Ice Bridge and the surprisingly soulful Leave Well Alone, Howe is a dominant presence, spinning webs of cleanly articulated riffs and solos that touch on jazz, blues, rockabilly and even twang.

On one of the record’s delightful highlights, Mystery Tour, an unabashed tribute to the Fab Four, he manages to capture George Harrison’s distinctive soloing style – there’s a sweet warble to the sound – with his own fleet-fingered approach.

In yet another first, Howe took on the role as sole producer, which he says isn’t really a big deal (“I’ve always been part of the production team”), only this album presented him with an unexpected challenge as it was recorded during the time of COVID. Because of travel and safety restrictions, various band members were sometimes together in studios in America and the U.K., but other times recording was done remotely.

None of which fazed Howe at all. “As a producer, my biggest role, beyond certain decisions that I had to make, was in setting a proper atmosphere, and that only comes through one’s communication skills,” he says. “If I can steer people’s performances in a good way and answer their questions, that’s half the job right there.

“As for file-sharing, that’s been around for over 10 years, so there was no strangeness to that aspect at all. It’s been perfected to a degree that there’s no loss of audio. If you can communicate to somebody what you’re looking for, you can work with them wherever they are, and in a way they can have even more freedom. It’s not a bad way to work.”

In previous interviews, you’ve talked about your influences as a guitarist, but you have to know that you’ve had an impact on so many players over the years. Do you ever hear from some of them?

“Oh, absolutely. It’s delightful to hear from people who are inspired by me, because really, they’re inspired by what I picked up from my heroes. It’s like we’re carrying on messages. I always appreciate the compliments and recognition.

“I can tell you that Chris Squire was very unhappy that we didn’t get into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame during his lifetime. He’d be pleased that we got it, but obviously he’d be sad that he didn’t get it, because he didn’t feel that Yes got the proper kind of acknowledgement from the business. He thought the industry turned its back on us a bit.”

The band’s performance at the Rock Hall induction was one of those things where past and present members took part. What was that like for you?

“It was strange, to say the least. It was like there were two sets of dialogue – one being that it would be nice if we all could have gone on and made music together. But the other thing was, there were issues, and some people had bigger ones than others.

“The lineup that had been given the green light by the Hall of Fame was just a moment in time. I knew there would be challenges, but you have to rise to them. I had to perform, and that’s what I did. Roundabout worked out not being too bad, really.

“I don’t own Owner of a Lonely Heart. We don’t play it – it’s the '80s band’s song. So for that performance, I learned Chris’ bass parts note for note, and I enjoyed, you know, ‘doing Chris’. I respected what he did, and that’s it. All in all, not a performance I would put in my top 10.”

You’re at the point in your career where each year is bound to bring up an anniversary. And as we approach 2022, we mark the 50-year mark of Close to the Edge, which routinely tops lists as the “greatest prog album of all time”. Where do you rank it?

“Oh, I place it right at the top, actually. When we started that album, there was such a feeling of ignition within the band. After Fragile, we knew that people were listening and were like, ‘What are they going to do now?’ We rose to the occasion. The song Close to the Edge was the moment in time when everybody’s contributions fired off in the highest possible way. [Producer] Eddy Offord, too.

“The other tracks were, too – they were identically identifiable and well arranged. The arrangement skills of Yes were coming through with Close to the Edge. I remember listening back to it in the studio and saying, ‘That’s pretty all right.’

Some of the reviews for the album at the time were pretty remarkable. NME actually said, ‘Yes aren’t just close to the edge, they’ve gone right over it.’

“That’s right. We were definitely feeling more confident, and that started with The Yes Album and into Fragile. We could do bigger tracks with longer intros, do more noodling, stopping and restarting. Everything was going ‘out there’ and we had some tricky arrangements. I mean, we were basically a rock band that fluffed it out a lot.

“Bill [Bruford] was the guy who said, ‘I’ll never play 4/4,’ and we didn’t expect him to. That’s what everybody was doing – finding their own voices. Bill was very adventurous, as evidenced by his decision to go and join King Crimson after Close to the Edge. He followed his heart. I’m not quoting him, but I think he thought Yes had gotten as commercial as he wanted us to be. It was so catastrophic when Bill said he was leaving. It sort of made no sense, but to him it did. I respected his view.”

How exactly did Alan White come into the picture?

“We were all hanging out with him in the studio before Bill left. Alan was a mate of Eddy’s, and we got to know him. We had a few “hang-out” guys. So when Bill told us the shocking news that he was leaving, there was silence, but then we all thought, ‘Well, Alan is a drummer, a really good drummer, in fact. We’ll go with him, right?’ We were in a jam, and Bill’s decision put pressure on us to replace him quickly.

“We got Alan in and played with him. He had to learn the whole set in four days or something. We had two rehearsals, and he bluffed his way through it. [Laughs] But if you’re a good musician, that’s what you’ve been taught to do. Nobody had really heard Close to the Edge yet, so there wasn’t anything to compare him to. Alan knew he didn’t play like Bill, but he rose to the occasion. There was a change in the band, but I guess it’s like when I came in and there was that change.”

You and Alan are now the longest-standing members of Yes. Is it fair to assume the two of you pretty much call the shots?

“Yeah, we have a strength of opinion based on our experience, and we can bring light to the dark tunnel sometimes by saying we’ve been through all these things before. I’m sure Alan and I have voices that are going to be listened to. But this is a team. This does rely immensely on teamwork, and pretty much things have to run through people, and they have to agree irrespective of their period in the band.”

There was that period in which Jon Anderson, Trevor Rabin and Rick Wakeman toured together. You and Alan didn’t take part in that. Was that a contentious time?

“Probably. That was just a futile thing they did. When they came out with the idea for it, I actually sent three emails to each of them saying, ‘Good luck,’ like, ‘It’s not going anywhere.’ But that was just true sentiment. I said to them, ‘Great. You’ve put a band together. Go with it. Good luck.’ I never heard back from them, but basically that was fine. They had their run. There has to be some competition in life, and they appeared to be what might be called competition.

“Basically, in their second year they decided to tack Yes on the front, and some promoters used the Yes logo, which they weren’t allowed to do. There was a bit of a pickle, but fortunately people woke up and said, ‘OK, we won’t do that.’

“It was a bit of a difficult time, because it was confusing, not only for the audience, but also for promoters. ‘Is this Yes, or is it Yes with ARW?’ It was a bit of a mess for a long time.”

Being in your position, is it like an extended family at reunions sometimes?

“You have to make peace with one another, and at times it’s difficult. It’s not difficult in certain situations. Some situations are really good, provided one keeps the same perspective and viewpoint that are most helpful to everybody going forward. Basically, you try not to jam things up.

“Whenever you leave a band, you might stay in touch with somebody, or you might not. The latter says something, in a way: ‘Look, I’ve done that, and we can’t really connect so much anymore.’ It happens.

“Sometimes you stay in touch with people that you don’t work with anymore. I never stopped being friendly with Bill, but we’re not working together. That’s ideal. It’s quite mature to accept something. If you can’t accept a situation, you keep rattling the cage and all you’re going to do is make yourself unhappy – and other people.”

Let’s get into some of the new songs. Dare to Know features such beautifully languid guitar melody lines at the top, and the volume swells you do are gorgeous.

“Thank you. Yeah, it was one in which I got more ambitious as I went. There’s several different frameworks to the tune, and of course, the orchestra comes in near the middle. The volume swells… it’s a Les Paul Junior and a pedal. I’m doing this drone without any harmonies. It’s a thick sound that I enjoy playing with.

“There’s the long intro. I’m mad about intros and endings. I’m the guy who always says, ‘Love the song, but it can’t start like this, and it can’t end like that.’ So it’s a song where I said, ‘Look, it just can’t possibly start like this. Love it, but it’s got to start like this.’ So I keep trying to stimulate other people to come up with more things.”

Yes is a rock band. We should try to use all facets of different mediums of rock to tell our story

Leave Well Alone has such a soulful rhythm – it’s almost R&B. Not what people normally associate with Yes.

“Well, I’m glad you hear that. Like I said, Yes is a rock band. We should try to use all facets of different mediums of rock to tell our story.”

The outro is signature Steve Howe, a stunning tapestry of clean guitar lines. Did you demo that? Was that improv?

“That was complete improv, and it’s pretty much what I played. I had a few takes, but that’s the take I like. Basically, I just started dabbling around with chords. I find different ways of leaning on them and crossing over them. I really enjoy guitar breaks, and that one is quite long. I sort of drifted out with it and made it reach a climax while other things were happening in the arrangement. The drums picked up and went to double time. All those things were very calculated, but they’re also improvised.”

On Music to My Ears, you and Jon Davison do a vocal duet. People forget what a strong singer you are.

“Well, thanks. Overall, I haven’t had many compliments about my singing. I do enjoy singing, and when you’re doing it with somebody else, you have to have the right sense of harmony. There are a few tracks on the album with duet vocals. On some occasions, Jon would say, ‘I could just sing what you’re singing, but what about us both doing it?’ That’s quite unique for Yes, but it goes back to Asia, with John Wetton and me singing.”

Your guitar playing dots the entire track, but it never seems intrusive. Do you ever have to pull back, like, “Okay, that’s too much. Stay in the pocket”?

“That might happen as I’m finding my feet. Sometimes I’ll play something and it’s over the top, so I’ll pull it back. There’s a certain kind of order and sensibility I like to bring to my guitar. One of the great skills of being any musician is being able to accompany a singer.

“It’s a big part of rock music. Beyond the moments when you get to do whatever the hell you like, it’s important to find out what you should do to support the singing. There are even times when you don’t need the guitar.”

A lot of people do Beatles tributes, but a lot of them are kind of cheesy. Mystery Tour is whimsical, but it’s not gooey or tacky.

“Oh, good. Thanks. I wrote about half the lyrics in 1985, and a year or so ago I found them and thought, ‘There’s kind of something here.’ Then I looked at my voice recorder and picked out the last tune I wrote, so that’s what I used. The song doesn’t quite sound like the Beatles, but it is a tribute to their greatness. I think they’re the best band that ever existed. They introduced such a broad spectrum of music in ways that hadn’t been allowed before.”

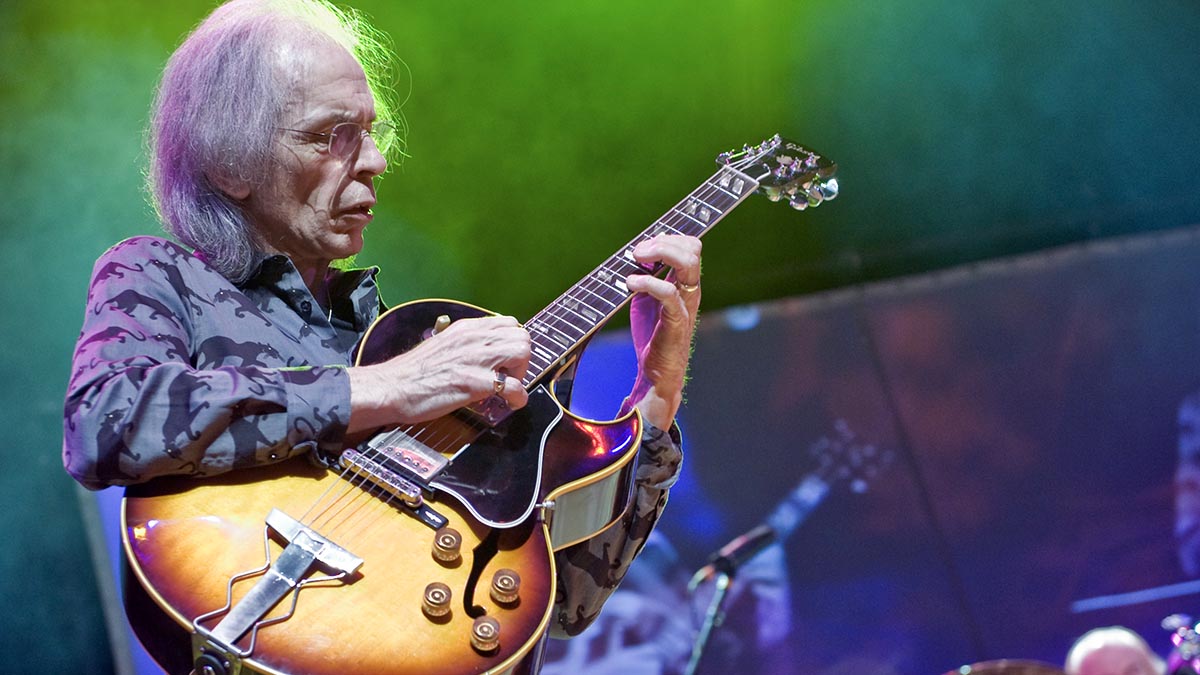

It’s interesting how in the solo you channel a bit of George Harrison’s sound and spirit, but you dovetail it with your own style.

“At first I wasn’t trying to do that. I’m not one to copy other people, but I thought, “I’m playing a Telecaster,” and if you remember during the Let It Be period, George was big on Telecasters. The solo’s got a few bends. It’s very casual and relaxed, like the whole song. I like that break a lot.”

Which Telecaster did you use?

“It’s my ’55 Relayer guitar. The pickup combination on that one is great.”

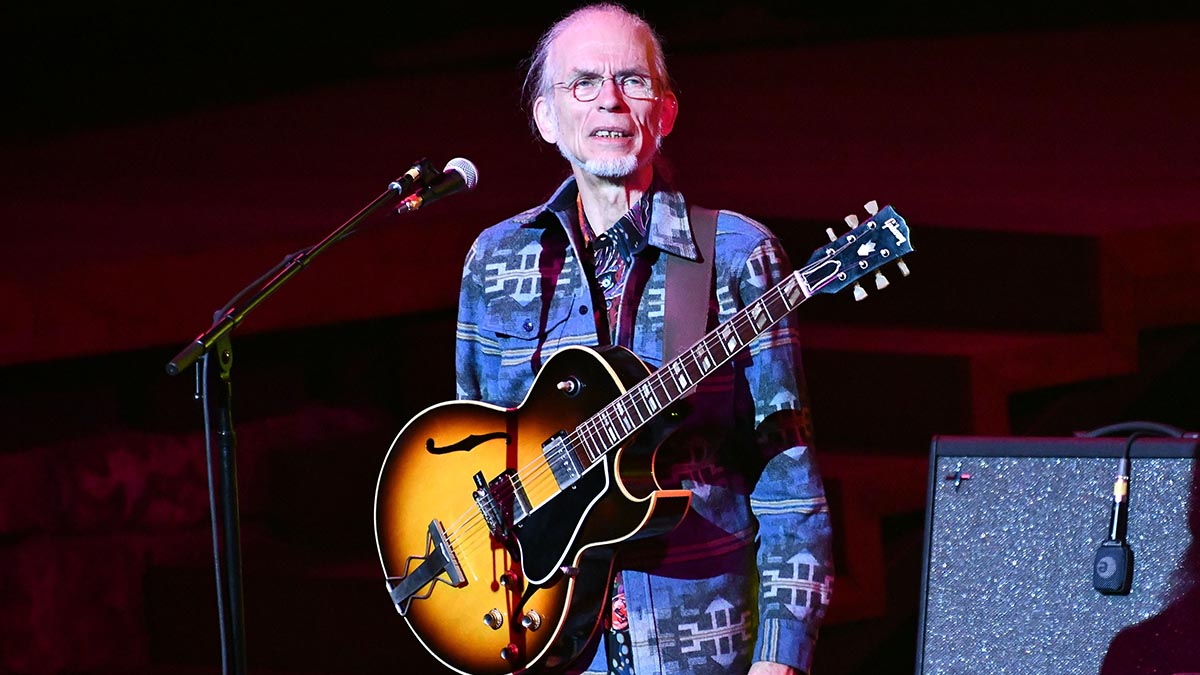

You always use your Gibson ES-175, and you mentioned a Les Paul Junior. What other guitars did you play on the record?

“I used the Les Paul Roland all the time. There’s plenty of reasons why I like this guitar, mainly because it isn’t heavy, so that’s unique. I played it at a trade show and said, ‘I’ve got to have this.’ I had Customs and an old Les Paul that weighed a ton, so this guitar felt quite nice. It became a workhorse, much like the Les Paul Junior. It’s nicely set up and has a Tune-O-Matic tailpiece. I love it.

“There are other guitars besides those. I used a Gibson ES-345, and of course, the ES-175. There’s steel guitar, which is a Fender Stringmaster. I love that. There’s some Stratocaster, and on The Living Island I played a Martin MC-28 acoustic. I played sitar and mandolin, and there’s a Portuguese guitar that got a spotlight. Quite a few guitars – they all seem to come out.”

Does having so many guitars at your fingertips ever feel like you have too many options?

“Not really, although I will say that I do like fewer choices in some respects. My collection is still too big. Gradually I’m whittling back, because I know there are key guitars that I must have for their sound. Danelectros, Rickenbackers and other things pop in the scene a little bit, but mainly, you can’t go wrong with Gibson and Fender.”

- The Quest is out now via Inside Out / Sony.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.