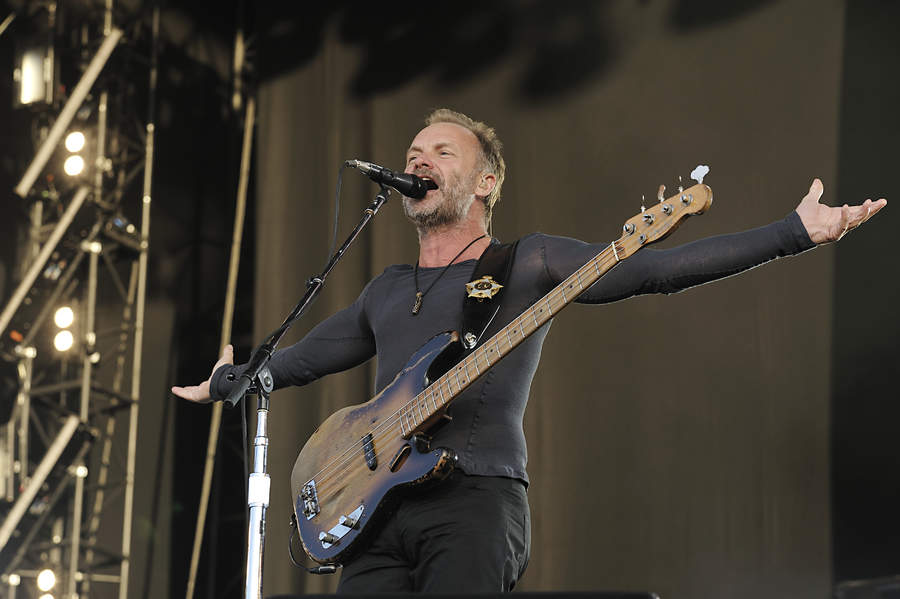

Sting: The secrets of steering a band from the low end

The superstar talks "57th & 9th", the "R" word and getting back to bass-ics

Mention Sting to us bassists and several hallmarks come to mind: His compositionally crafty, sparse bass parts with the Police. His ability to sing lead on his songs while playing independent bass lines, in the grand trio tradition of Jack Bruce and Geddy Lee.

And his jazz-infused, post-Police explorations, which further anointed him a darling of the musician crowd without affecting his gift for selling millions of records to the general public.

Since Sting’s last BP cover (March 2000), following the release of Brand New Day, his restless musical soul and inherent curiosity have led him down different avenues, with a 2007 Police reunion tour in the mix.

There was Sacred Love, his mildly received 2003 follow-up to Brand New Day; Songs from the Labyrinth, his 2006 collaboration with lutenist Edin Karamazov, playing the music of 16th-century English composer John Dowland; his 2008 Christmas album, If on a Winter’s Night, mixing traditional folk songs with several similarly intoned originals; 2010’s Symphonicities, an orchestral take on a dozen Sting standards; and The Last Ship, first a 2013 album and then an all-too-brief-running Broadway musical.

While most of these recorded journeys featured upright bassists like Christian McBride or Ira Coleman, Sting—equipped with a new fingerstyle approach to bass from his classical-guitar and lute forays—“returned” to the instrument for live shows, revisiting his 25-year span of hits and even dubbing his three years of road stints “Back to Bass” tours.

Now the R-word is being used in conjunction with Sting’s excellent new album, 57th & 9th, named for the Manhattan intersection near the recording studio.

While many are labeling 57th & 9th Sting’s “return to rock & roll,” the ten-track disc visits all phases of the musical career of one Gordon Matthew Thomas Sumner (born on October 2, 1951, and raised in Newcastle, England).

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The added wrinkle here is that most of the material was spontaneously group-composed with such trusted longtime band members as guitarist Dominic Miller and drummer Vinnie Colaiuta, as well as veteran session guitarist Lyle Workman and drummer Josh Freese (Nine Inch Nails, Guns N’ Roses, Weezer).

That’s where we began our conversation with Mr. Sumner…

Is it true you brought in no songs for this album?

Yes, I brought in virtually nothing. On the first day, I said, “I have a confession to make: I have no idea why we’re here and what we’re going to do. Let’s just play and ping-pong some ideas,” and something came that very first day.

Normally I’ll come into the studio with songs and arrangements and ideas about what should be played. But in this case I thought, Well, my band knows what I like, and I can hear when ideas work, so we can spontaneously compose together, which was very exciting. The music is a product of our long-term relationship.

How did having a three-month deadline factor in?

I think it helped; the record has an energy that perhaps wouldn’t have been there had it been my normal method of simply working until I felt the music was ready.

I’ve always said the creative animal we’re trying to capture is very ephemeral. You have to change your method, change your angle and point of view to capture it. It’s like hunting.

How did the album’s more immediate nature affect your approach to the bass lines?

On previous records I’ve tended to add my bass later in the process. That wasn’t the case here, because we jammed so much of the music. I was playing the whole time and operating on a compositional level as we went.

My bass parts were pretty much as they were laid down. As for my approach, it has always been about the same. I regard myself as the engine room of the band. I don’t intend to be flashy; I just function. If that means playing roots two to the bar or one to the bar, I don’t care.

Occasionally, I will throw in a 3rd on the bottom just to make things interesting, but I’m there to serve as the bed of the group. And when you’re the singer, as well, it means the band is operating within your own bandwidth. So it’s a good way of being a bandleader without waving a stick around!

Bass players often dig that your bass is the only instrument defining what the chord is, as is the case with the opening single, “I Can’t Stop Thinking About You.”

I always say, It’s not a C chord until I play a C. You can change harmony very subtly but very effectively as a bass player. That’s one of the great privileges of our role and why I love playing bass.

I enjoy the sound of it, I enjoy its harmonic power, and it’s a sort of subtle heroism; it’s not the lead guitar part playing lots of hemidemisemiquavers [64th-notes] to the bar. It’s basically solid workman-like effort.

Another song totally defined by the bass line is “If You Can’t Love Me.”

That’s a descending bass line, and they’ve been around a long time; some bands get sued for them [laughs]. But they work every time. There’s a profundity to them. You’re going down, and the song becomes more intense and profound the deeper the bass line goes.

Here, the chords get more dissonant and the tension grows. [Guitarist] Dominic Miller and I co-wrote the song. It began as a dominant guitar riff, and then we added the descending scale, and that’s how we found some sense in it.

Dominic has been working with me for close to 30 years. We have an intuition and a trust about each other, and he constantly surprises me, too. He’s a terrific musician who loves to explore harmony, as I do.

Even going back to your first band, Last Exit, your bass lines had a compositional quality. What do you credit that to?

I’ve got good ears. I’m a self-taught musician who never went to music academy. I got gigs not because I was particularly good at reading charts, but because I could hear where the harmony was going.

When I would go to auditions and they asked me if I could read, I’d say, Yeah, I read the ad to show up here! Eventually, I taught myself to read. But to me the most important organ in any musician’s arsenal is the ear. It’s more important than your fingers, than the strength in your digits. It’s the first step; the first step to making music is to hear it.

Also, I’ve always worked with musicians who are way better than me. It’s the same with sport—if you play tennis with someone who isn’t very good, your game won’t improve. If you are lucky enough, as I have been, to play with some of the best musicians in the world, then you have to raise your game to stay in the game.

“One Fine Day” has the same Lydian tonality as your 1994 song “When We Dance.”

I have my favorites, for sure—certain things my fingers find on guitar that please me. I’ve always said music is an obsessive-compulsive disorder: The ideas that please you, you keep returning to again and again. In many ways, music is a puzzle; you’re finding your way out of a maze.

How to change keys has always intrigued me, and it’s something I’ll use in my songs, how to get from one key center to another without being clumsy. Even just going up a semitone, which is a truck driver’s key change—how do you disguise that and make it mysterious and almost invisible? I’m intrigued by music. I can’t say I’ll ever get to the bottom of it, but I love being in puzzle-solving mode.

Your “One Fine Day” bass line has upbeat pushes on the tonic that give it almost a Latin feel. Was that conscious?

That was completely unconscious. I’m a total gadfly about styles and influences. I want the songs to reflect that kind of universal interest in music rather than a genre-based interest. I’m really most intrigued by music you can’t label.

Even if it’s a standard pop song, it should reflect my entire musical DNA, and I think this song does. I think this album does, actually. People have said this is my return to rock & roll, and I understand the lack of keyboards and the heavier, edgier guitar sounds are a factor in that—but my initial response was, I never left rock & roll.

I’ve been playing every night of my working life, and how do you define rock & roll, anyway? This album reflects what has intrigued me since I was a kid, what I’ve studied, who I’ve played with, what I’ve attempted. All of that gets fed into a pool, and I drew from that.

How did you come to bass, and who were your key early influences?

I had been a guitar player working in clubs, and then someone lent me a homemade bass, and I fell in love with it—the dimensions, the aesthetic—and I realized I could play bass and sing. I learned how to play Paul McCartney’s parts on Beatles songs and sing them at the same time.

I’d speed up my record player to 78 so I could hear the bass lines more clearly. And then came Jack Bruce, dear, wonderful Jack, who was an amazing jazz musician and a great jazz singer in a rock band! I also worked my way through the Ray Brown bass book and studied scales and arpeggios—the kind of material you get through once and you’ve learned a universe of knowledge.

What else factored in?

I was a big fan of R&B, James Brown, Otis Redding, Motown and bassists like James Jamerson and Carol Kaye—music where the bass has a huge effect. The same with reggae, which has always been in my ears because London was the center of reggae.

I’ve always had an affinity for playing reggae bass, while American bassists tend to struggle with it. Overall, I was more attracted to the thick, thumpy bass in R&B and reggae. I didn’t care much for the thin, wiry sound a lot of English bassists had, brilliant as they were.

And out of all of that came your ability to sing while playing an independent bass line.

Yes, basically from trying to be a functional bassist and not get in the way of my singing. People say I leave a lot of space in my bass lines—well, that’s the way I sing! [Laughs.] But I do enjoy the puzzle of how to sing against a contrapuntal bass line. As we bassists know, it’s not the same as strumming four to the bar on guitar, while singing.

It takes a bit of division of thought. But if you slow it down, break down the components, and speed it up gradually, anything can be played and sung at the same time. It’s just practice; there’s no magic to it, you put the hours in. It’s a skill I’ve developed.

Is your ’57 Fender Precision the only bass you play on the album?

Yes, it’s the only bass I want to play; I’ve had it for almost 25 years. I’ve got a backup ’57, but this particular ’57 has a growl that I can’t find in any other bass. It has a single-wound pickup probably wound by Mr. Leo Fender himself, and it has gouges and wear, but it has a spirit.

I think the more music you play on an instrument, the more responsive and better it gets. I’ll pick up a new bass occasionally, but I’ll put it right down. I want an instrument with some history and character and feel.

Bass Player had the opportunity to play Jaco’s recovered Bass of Doom. His famous lines seemed to almost play themselves; you could feel all the hours he spent creating on it.

That’s remarkable. Speaking of his bass lines, I’ve been revisiting “Teen Town” of late, and I play it at soundchecks. Jaco recalibrated the whole idea of what it meant to be a bass player. His playing and his choices on that tune particularly still blow me away.

And you knew him.

Yes, I knew him personally; he used to come and see the Police down in Miami. He was a brilliant musician and a lovely guy. I miss him. His death was so senseless and unnecessary. I’d be fascinated to know what he’d be up to now, musically, had he survived.

On both “Inshallah” and particularly the Berlin Sessions version of the song, your ’57 Precision sounds like an upright bass.

The upright is something I aspire to; I love that sound and tone. I first played it when I was in school, and then over the years with the Police and on my records. However, unless you play it every day, you can’t keep your chops up, so I’ve had to leave it behind for the most part.

But my Precision does have an organic growl, so if you’re hearing an upright bass, that makes me happy. For the bonus version of “Inshallah,” we went to Berlin and played with some Syrian refugees who’d found a home there, who were all from Aleppo. Aleppo was the music center of the Arab world. Musicians would go there to learn their craft.

These guys told me their stories, how they escaped and got to Germany, their philosophies of music. The song is not for any political solution— I don’t have one—but it’s an exercise in empathy for people who are running from terrible violence and cruelty. I think it’s important for all of us to imagine ourselves in that position. It could happen to us one day; who knows?

On “50,000” and “Petrol Head” I’m hearing low D’s and C#’s on the bass.

That’s me detuning my E string, as I occasionally do. I rarely use a 5-string—it confuses me!

Beginning with your Back to Bass tours a few years back, you’ve been playing bass lines from your entire career. Would you say you’re playing any of them differently, or that your style has evolved?

I’m always looking for innovation when revisiting songs. The main difference is I’m using my thumb and two fingers tucked underneath, in a sort of apoyando style, which not many bass players use.

That began in the ’90s, from having played guitar all my life and being interested in classical guitar technique, and then playing the lute, which had six bass strings and 26 strings in all. I became intrigued by righthand technique and how much choice you have.

My thumb is forward and the two fingers are behind that, which I’ll use to get a tremolo effect. I worked opposite Tony Levin on tour with Peter Gabriel last year; he was watching me and he said, “Wow, I’ve never seen that before.” Then I saw him trying it [laughs].

Back with the Police I was playing bass with a pick, and I often doubled bass lines on guitar, which gave a very pointed, precise tone. Now I’m into a rounder, warmer sound.

You play a lot of chugging eighth-notes on the album. Are you using your thumb for that?

Yes, I use thumb downstrokes with lots of damping with my palm and left hand. I think eighth-notes are very powerful. Also, I tend to push the tempo against the backbeat when I play them; I think that tension, with the drummer sitting back, is what gives the music its excitement—just like harmonic tension can create.

Has playing with Vinnie Colaiuta for many years had an effect on your style?

There’s no doubt. Vinnie and I have a great relationship, one of trust. The only thing I’ll tease him about is the double bass drum. I’ll say, “Hey, where am I in this equation?” And he’ll crack up laughing.

There has to be a tradeoff, as the bass and the bass drum are very important as partners. Vinnie is an extraordinary musician who has been with me for almost 30 years, on and off, and I appreciate all that he adds to my music.

I’ve been blessed to work with the best drummers in the world: Stewart Copeland, Omar Hakim, Keith Carlock; I’ve got Josh Freese on this tour, while Vinnie is working with Herbie Hancock. Let’s face it, a band is only as good as the drummer.

Let’s talk about some of the top bassists you’ve hired over the years.

Sure, like the Munch Man [Darryl Jones], Christian McBride, Ira Coleman, Will Lee. I have a tremendous respect for bass players; I understand the lineage they come from. And it’s great to have a holiday some nights so you can just sing.

People like Will or Ira or Nathan East will come to my aid and give me that holiday. I do listen, though, and if I don’t agree with something, I’ll let them know [laughs]. I’m also very sensitive to bass volume, because bass frequencies are everywhere; they’re multi-directional.

You don’t need to be that loud. I’d rather the volume came from the actual playing than from an amplifier. If you’re playing behind the volume of an amp, you can really play. But if the volume of the amp is playing you, that’s different. I prefer a quieter bass, a felt bass, rather than something that’s overbearing.

Early on, I played bass guitar in a big band, and I learned very quickly how to blend using an amplified instrument rather than overpowering the horn section. That was a great lesson for me.

Have any bassists caught your ear these days?

I love Metallica’s Robert Trujillo. He’s not only a great bass player, it’s the drama of how he plays, and he’s a showman, which I think is fantastic.

I’m also impressed with the emergence of excellent female bassists. I’ve played with both Tal Wilkenfeld and Esperanza Spalding. With Tal it was very funny; we were doing an event in Las Vegas, and we were playing an Aerosmith song—I forget the song—and it was kind of a complicated bass line.

And Tal came over and said, “Sting, it’s not quite the way you’re playing it” [laughs]. I really respected her courage to come up to me and teach me the right way to play the part, and I was very grateful. She’s an amazing bassist with great ears.

And Esperanza, my god, she’s a triple threat—she writes, she’s a fantastic singer, and she’s an incredible bass player.

There’s a trend in younger bands across the musical spectrum of having no bass player. Do you have any concerns?

It doesn’t worry me. Various types of instrumentation go in and out of fashion, but the Fender bass will be with us forever. My daughter plays bass and sings in her own band. I gave her one of my signature Fender Precisions, which are lovely instruments. She’s very good and a great singer, too.

What lies ahead?

I’ll tour most of the year, and Peter Gabriel and I would like to go out again, maybe in 2018—we had a great time. My work is kind of seasonal: I have a season when I’m thinking, a season when I’m writing, a season when I’m recording, and a season when I’m playing. They rarely coincide; I don’t think much about composing when I’m on tour.

Right now I’m solely looking forward to playing these songs onstage every night. There are very few studio tricks on the record, so it will be fairly easy to reproduce and enhance. Then it’s up to us to incrementally change the arrangements.

Something will occur every night as we play them, sometimes by accident, sometimes by design. Songs are meant to evolve—they’re living, breathing, organic things. That’s why I love touring: You rediscover the songs.

LISTEN Sting, 57th & 9th [2016, A&M/Interscope]

Sting’s ’57 fender precision is the sole bass he uses on 57th & 9th, appearing on nine of the 13 tracks on the album’s deluxe edition. Danny Quatrochi—who could well be the longest-tenured bass tech in the biz—keeps the ’57 in top playing shape, with its well-worn two-tone sunburst-finished, contoured ash body, maple neck, and single-coil pickup.

The New Jersey-born Quatrochi joined the Police as a tech in 1979, and he has been with Sting through all of his successive solo albums and tours. “Sting got that bass in the early ’90s, when he was filming a video for ‘Demolition Man,’ for the movie of the same name,” says Danny.

“They got him a worn-looking bass to play, and he fell in love with it and bought it. I have an identical ’57 Precision as a backup on the tour.” Sting’s action is normal to a little high, and he uses DR Strings Nickel Lo-Riders NLH-40 (.040, .060, .080, .100), changed every show.

Sting’s live signal chain, reports Quatrochi, starts with a Shure ULXD wireless, going to a custom Pete Cornish rack switching unit (which also contains a DI that goes to monitors and front-of-house), to an Avalon Vt 737 preamp and a Lab.Gruppen PLM 20000Q power amp (all off to the side and controlled by Quatrochi), to two onstage Clair Brothers ML18 cabinets topped by two Clair Brothers 12AM cabinets (with a 12" speaker and a horn).

Side fills and front monitor wedges have a full band mix, while Sting’s custom JH Audio in-ears (he keeps only the left ear in) contain vocals and a bit of bass and kick drum. “Sting and the whole band are great with dynamics. I don’t have to change his volume all night, although occasionally I’ll turn him down a bit on a ballad.”

Tony Lake, who recorded 57th & 9th, offers, “Sting’s bass was recorded direct, either through an Avalon tube pre or a Neve 1073. I didn’t add much compression—just a little Universal Audio 1176 with a high threshold to even it out a bit when things got loud. For a few of the songs, we miked an Ampeg rig to give Robert Orton, who mixed, some options.”

He adds, “Sting is a phenomenal bass player. His note choices, time, dynamics, and right hand are incredible. He can dial in his touch to give a smooth fretless feel on his legato parts, and when he tunes his E string down, he has the ability to still get a lot of power and definition without it sounding floppy.”

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.