“He showed complete mastery of the bebop jazz language – a language invented on horns”: Celebrating Joe Pass, jazz guitar’s great re-inventor – and a player who had the rare ability to nail sax lines on a six-string

Bona-fide jazz legend Joe Pass had it all. Here we celebrate the life and career of on of jazz guitar's most fluid and fluent players

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Joe Pass was born Joseph Anthony Jacobi Passalacqua to Sicilian immigrants in New Jersey on 13 January 1929. He acquired his first guitar at the age of nine after being captivated by country legend Gene Autry’s appearance in the 1940 movie Ride, Tenderfoot, Ride.

It wasn’t long before Joe’s interest became an obsession and he would practice for two hours before school and two hours after, and then continue for four more hours after dinner before he went to bed.

His father drove him relentlessly and would ask his young son to work out – on the spot – any tune that happened to be on the radio. He also encouraged him to embellish melodies as he heard them. At that time Joe didn’t know what improvising was. To him it was “filling up the spaces”.

By the age of 14, Joe was out gigging at parties and dances. His father, a steel worker, was astonished that his son could earn more than he could: $5 per night.

It was around this time that Joe developed an interest in jazz. His primary influence was Django Reinhardt, whose records were now starting to appear in the United States, inspiring and frightening guitarists in equal measure.

Joe further expanded his jazz education when he discovered the electric guitar pioneer Charlie Christian through his recordings with the ‘King of Swing’ Benny Goodman.

From there, Joe took influence from a number of burgeoning young jazz guitarists of the 1940s such as Barney Kessel, Tal Farlow and Jimmy Raney. As Joe said: “These guys added another dimension to the instrument.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Time With Montgomery

Later on, Joe took to the playing of Wes Montgomery. Little did he know that some years later the admiration would be reciprocated. So it was that in 1968, when Montgomery was at the peak of his popularity, he appeared on television’s The Woody Woodbury Show.

When the host asked the spotlighted player who his favourite guitarist was, Montgomery pointed at the house band, declaring: “He’s sitting right there in your band!” The band’s guitarist was Joe Pass.

In the mid-1940s, and still a teenager, Joe was sent to New York to study with the guitar legend Harry Volpe. After discovering that Joe was the better improvisor, Volpe switched to teaching Joe sight-reading, which didn’t interest the student at all. He left for home, but the buzz of New York City had left its mark on the young jazzer and he so soon moved back to the city.

Pass was now spending his time taking in as much of the great jazz scene that NYC had to offer, soaking up the music of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Art Tatum and other jazz mavericks of the era. But it was also at this time that he picked up a drug habit, something that was to plague his life for the next 15 years.

Joe spent these years hopping from town to town, weaving in and out of prison and rehab. He played bebop for strippers in New Orleans, often staying up for days on end and constantly pawning his guitar. He also spent time in Las Vegas picking up any gig he could. He summed up these years by confessing “staying high was my first priority”.

In 1954, Joe was arrested and sent to the Public Health Service Hospital in Fort Worth, Texas, where he served four years. Following his release, in 1960 he entered Synanon, a rehabilitation centre based in Santa Monica, California, and it was there that he finally started to look at his life and career more seriously.

Two years later he made his debut recording, Sounds Of Synanon, which also featured five other jazz musicians who were resident at the facility. The influential publication DownBeat stated the album “unveils a star in Joe Pass.”

Living A Full Life

Much of what Joe Pass is known for today is present on Sounds Of Synanon and other early recordings. Like his idol Wes Montgomery, Joe didn’t record too young and was in his early 30s when he made his recording debut.

This meant, after years of playing in clubs all over the US, Joe’s blistering and impressively accurate technique was unleashed fully formed on the record-buying public.

Joe’s incredible improvisational skills and technical prowess were saved for the perfect moment

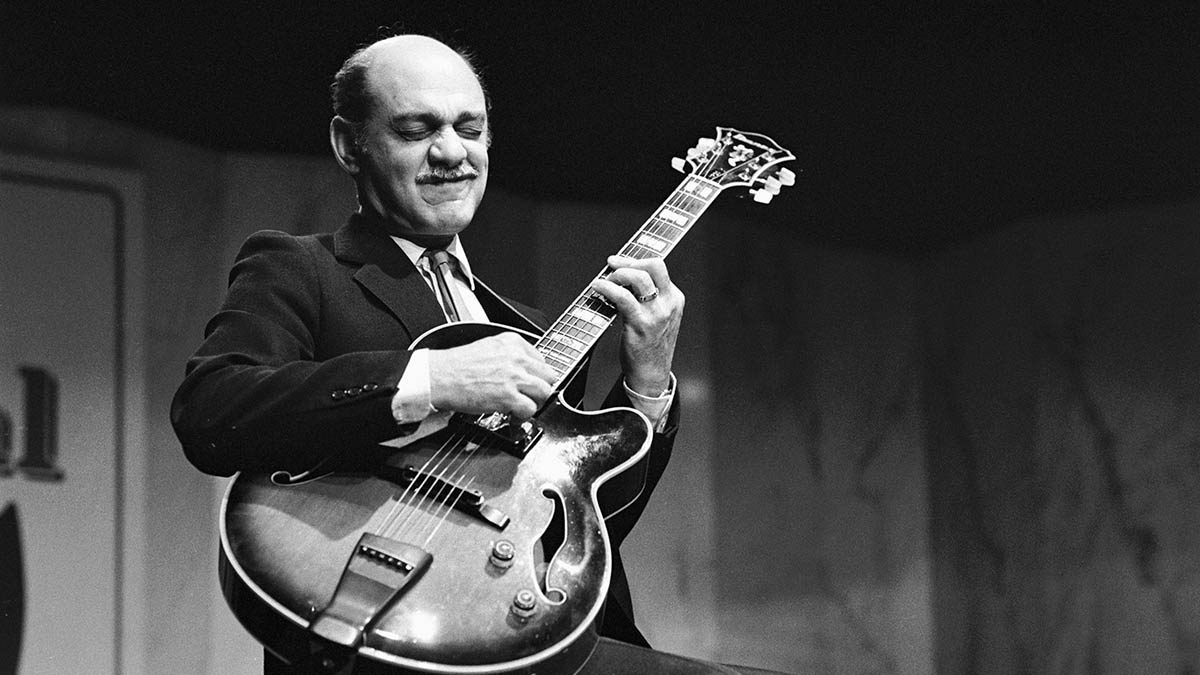

Pass may well have been the first electric jazz guitarist to possess the technical facility to hold his own among the sax and piano players of the time, but it wasn’t just about speed. His ideas were so melodic and well crafted; it was never just a series of fast scale-runs.

He showed complete mastery of the bebop jazz language – a language invented on horns. And for anyone who’s tried to play a Charlie Parker theme at speed on the guitar, they’ll know it’s not easy.

Those lines don’t sit under the fingers in the way a pentatonic scale does. Joe, however, found a way and it sounds so smooth and legato-like that it could almost be sax.

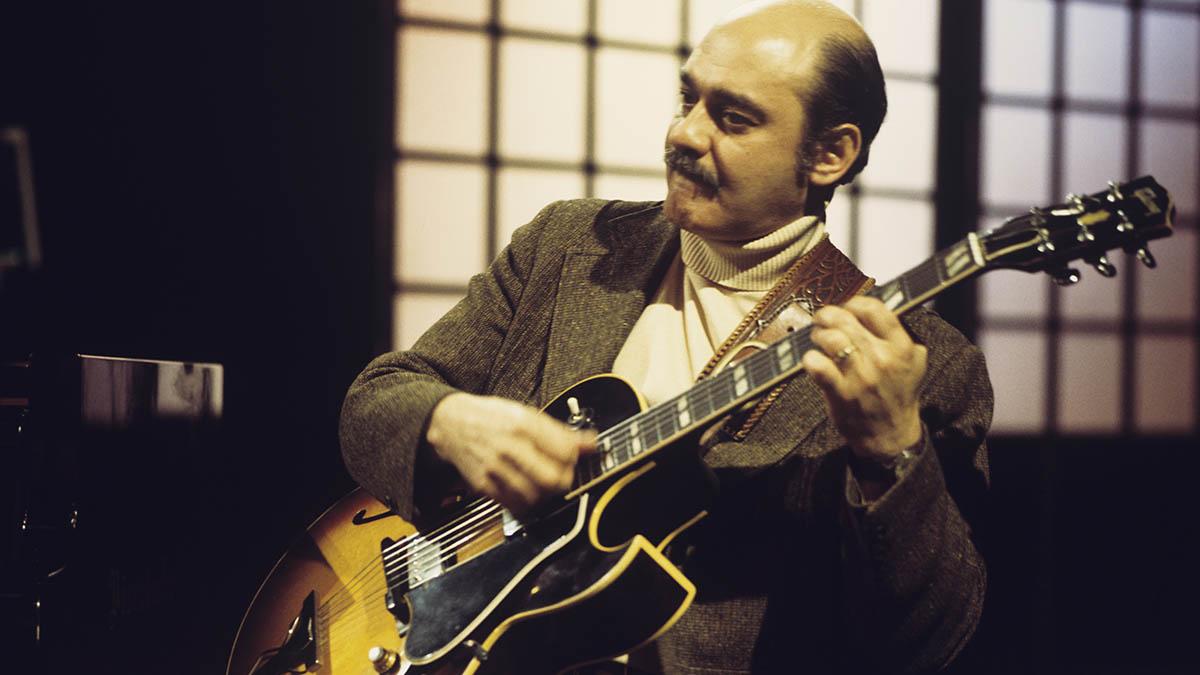

The legend was that Joe didn’t own an electric guitar at this time, and he used a loaned Fender Jaguar for his early life outside rehab. Shortly after, as work became more stable, he acquired the guitar that he’ll be forever associated with, the Gibson ES-175.

Plenty of jazz guitarists used the 175 as their go-to instrument and still do. With a slightly smaller body than the Gibson L5 (Montgomery’s choice), the 175 also has a laminate top that tightens up the sound and makes the guitar less prone to feedback.

For the rest of the 1960s Joe spent most of his time working studio sessions and TV shows. This work was steady and well paid but anonymous. The busiest session players during those years were jazz musicians – because they were the ones that knew how to play anything that was thrown at them in the studio.

To this day, most people are unaware that the biggest pop hits in America were recorded using jazz musicians. Joe was one of them, but he wasn’t especially happy and, like many others, had quit the scene by the early 70s.

Elevated Jazz

In 1973 Pass met record producer Norman Granz who, with his organisation Jazz At The Philharmonic, had managed to elevate jazz from club to concert hall. On Granz’s roster were the likes of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Oscar Peterson and Ella Fitzgerald.

He paid his musicians well and had formed Pablo, a record label, to create hundreds of albums with stars such as Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong and Count Basie.

Joe signed with Granz’s label in late 1973, and, shortly afterwards, released the groundbreaking and influential album Virtuoso. Comprising 11 jazz standards (and one off-the-cuff blues), it’s an album that every guitarist needs to hear.

Norman Granz put Joe, with no backing band, in a studio and set the tapes running. What comes out is something extraordinary and all of it is improvised. Most solo guitarists would have probably worked out a few routines, but not Joe. If he’d recorded all the tunes again the next day, then they would have sounded completely different.

Each tune was taken apart and reassembled on the spot. Joe embellished the melodies with a heady combination of fret-melting single-note runs and block-chording, all delivered with such skill and playful abandon that surely Django Reinhardt himself would smile in appreciation. It was the album that truly put Joe on the musical map and remains one of Pablo’s best-selling releases.

Three further volumes of Virtuoso were recorded. Granz then teamed Joe with piano giant Oscar Peterson and Danish bassist Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen for the album The Trio, which went on to win a Grammy. The three musicians became a regular touring group throughout the 70s and 80s, taking Joe all over the world.

Joe also collaborated with Ella Fitzgerald, and the pair recorded four studio albums together between 1973 and 1986, as well as several live releases. This revealed another side to Joe’s musicianship, demonstrating a sensitive and complementary accompaniment to Ella’s sublime vocals. Ella and Joe enjoyed a deep connection and friendship that shone through on everything they played together.

An Education

Joe produced several instructional books throughout the 1980s. These manuals, which are still in print, each focus on a different aspect of his impressive range of skills; it’s rare to find a jazz guitarist who hasn’t tried to absorb some of Joe’s genius by poring through the volumes.

Later, Hot Licks produced two instructional videos featuring Joe: Solo Jazz Guitar and The Blue Side Of Jazz. These are still available and are full of tips from the master, all delivered with his charming humour and dry wit.

In the early ’90s Joe’s health started to decline, and in 1992 he was diagnosed with liver cancer. He continued to play and record up until 16 days before his death on 23 May 1994, at the age of 65. His last recording was a collection of Hank Williams songs, with guitarist and vocalist Roy Clark. In total, Pass appeared on more than 70 albums as either leader or sideman.

So much of Joe’s later career was dedicated to teaching. He toured college campuses and held masterclasses and workshops all over the world. His entire philosophy was to make jazz guitar simple and accessible. It was something he succeeded in doing. In one of his masterclass videos Joe is asked about his choice of chord shapes.

A smile appears as he explains he doesn’t go for long finger stretches or too much in the way of harmonic extensions. “I like the simple shapes, the ‘grips’ I call them. If it’s hard, I don’t do it!”

I like the simple shapes, the ‘grips’ I call them. If it’s hard, I don’t do it!

Many guitar players will perceive Joe’s music as far from simple yet it does have a simplicity to it. One that gets straight to the point, straight to the heart of a song. Joe had that rare ability to play exactly what was right in any given moment. Yes, there are, at times, a lot of notes, but they were never gratuitous. He wasn’t interested in impressing other guitar players, although he most certainly did.

Joe’s drive was to serve the music first and foremost. His incredible improvisational skills and technical prowess were saved for the perfect moment. It might be a cliché to say ‘they told a story’ when describing how certain legendary musicians play, but this is an accurate way to assess Joe’s approach. Some people operate the guitar, but Joe Pass really played it.

Denny Ilett has been a professional guitarist, bandleader, teacher and writer for nearly 40 years. Specializing in Jazz and Blues, Denny has played all over the world with New Orleans artist Lillian Boutté. Also an experienced teacher, Denny regularly contributes to JTC and Guitarist magazine and is founder of the Electric Lady Big Band, a 16-piece ensemble playing new arrangements of the music of Jimi Hendrix. Denny has also worked with funk maestro Pee Wee Ellis and is the co-founder of Bristol Jazz & Blues festival.