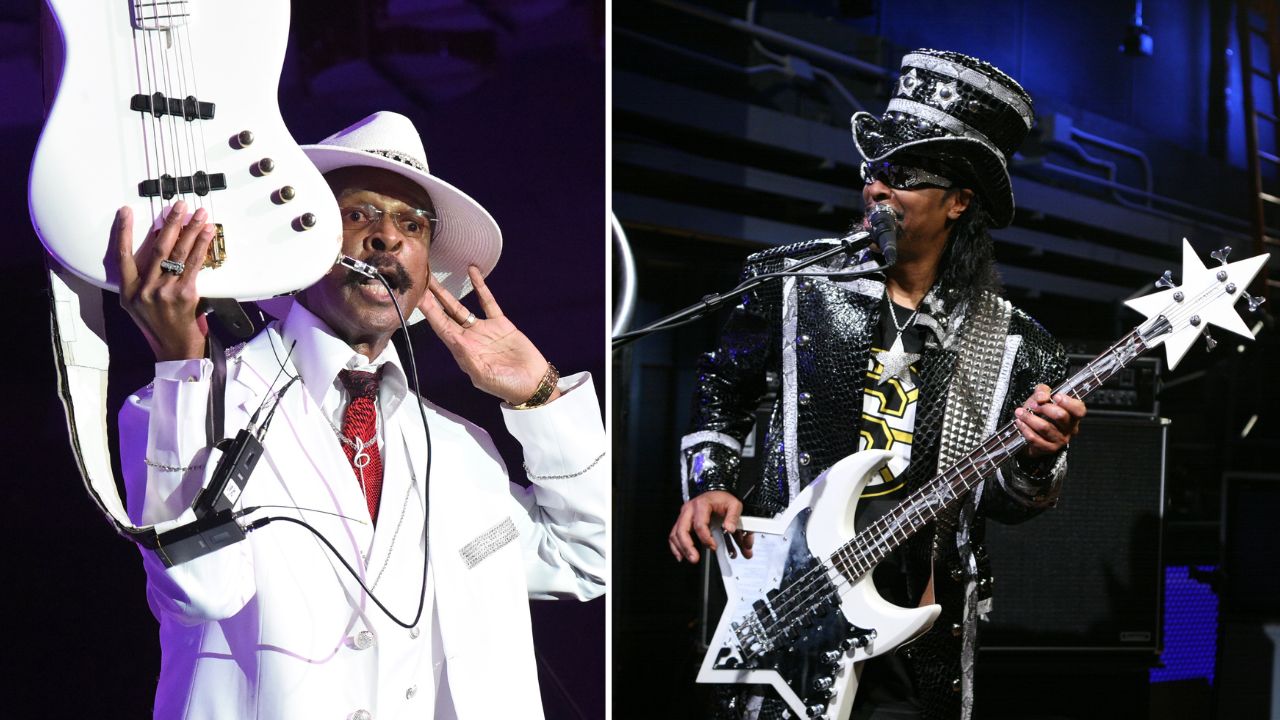

When Bootsy Collins met Larry Graham: “He handed me his bass, and I said, ‘Don't even try it. You play the bass, and I'll just watch’”

Why did funk legend Bootsy Collins refuse to jam with the godfather of slap bass?

Bootsy Collins isn’t an easy character to make star struck. There’s probably only a handful of people on the planet who would make him feel in awe, but the first time he met Larry Graham will live with him forever.

"I first saw Larry around the time I was with James Brown," said Bootsy. "I thought, 'How is this cat playing with his thumb?' When I got with Funkadelic, Larry invited me to his place to jam. He handed me his bass, and I said, 'Don't even try it. You play the bass, and I'll watch.' He's the ultimate slap machine. I will never be able to do that technique as well as he does.”

Bootsy eventually recorded with Graham for a cover of Sly and the Family Stone's 1973 hit, If You Want Me to Stay, which appears on Collin's 2020 album, The Power of the One. As he told Rolling Stone, he’s always admired his fellow bassist for pioneering the “thump and pluck” style. “And that is why to this day I call him the Basses Mutha Plucker this Side of the Universe!”

More than half a century after Larry Graham first invigorated Sly & the Family Stone standards like Family Affair and Everyday People, his game-changing slap technique remains a staple of bass guitar vocabulary.

"The thing is, I never saw myself as a revolutionary," Larry told BP. ”All I was doing was what sounded good to me, but it became an accepted way of playing the bass, to the point where people take it for granted. Most of the young kids you see doing thump-and-pluck don't even know who I am.”

The following interview is from the September 1996 issue of Bass Player.

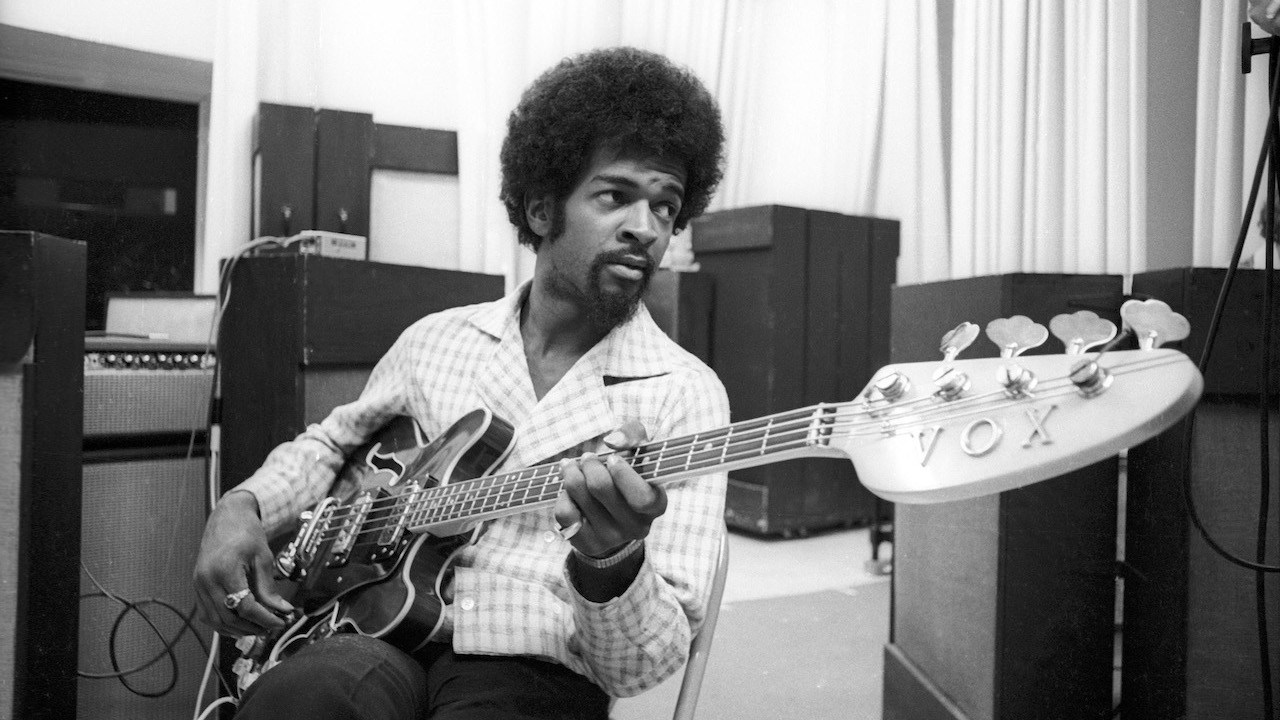

Though he's Texan by birth, most of Larry Graham's musical growth took place in Oakland, California. His family – which included a guitar-playing father and a jazz piano-playing mother – moved there when Larry was two. An early student of drums, Graham later picked up the clarinet, sax and guitar, listening to the likes of Ray Charles, Nat King Cole, and Frankie Lymon & the Teenagers.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

By the time he was 15, Larry was accompanying his mother at clubs around town; it was then that he switched to bass and started developing his iconic style. "We had a trio with me, my mother, and a drummer. One club we played at had an organ with bass foot pedals, and I found a way to use the foot pedals while playing the guitar." When the organ broke down, Graham switched to bass, hoping to fill in the low end until the organ was back in commission.

As fate would have it, the organ never got fixed, leaving Larry on an instrument he never intended to play full-time. "I went out and got a bass. I wasn't concerned with playing it in the traditional way, because I didn't see myself as a bass player. In my mind, I was still a guitar player, so I didn't care that bass players might think I couldn't play or was doing it wrong."

Then something even more crucial happened: the band lost its drummer, which left Graham as the entire rhythm section. "That's when I started thumping with my thumb. It was the only way I could get that rhythmic sound." But Graham didn't just adopt a rhythmic attitude: he transferred actual drum figures to the bass. His thumb would play the kick-drum parts, and his plucking fingers would simulate snare rhythms. This simple-sounding concept turned the bass guitar into a hybrid instrument, capable of interacting with a drummer while still holding down a supportive role.

Graham mastered his new approach while he and his mother gigged around San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury scene. After a few shows at a place called Relax With Yvonne in 1968, Larry caught the attention of a popular local deejay named Sylvester Stewart – also known as Sly Stone – who was looking to put together his own band. "One particular woman came in all the time and she loved us," says Larry, "and she was also a fan of Sly, who was on KSOL radio at that time. When she heard Sly was trying to put together a band, she told him to come check us out. And he did."

Sly and the Family Stone were soon riding high on a string of hits, but the group's fame magnified Stone's egocentric and often self-destructive tendencies. By the early '70s, his behavior had become increasingly erratic, resulting in a slew of missed appointments and concert no-shows. Sly also alienated band members by overdubbing tracks himself, including several on the epochal There's a Riot Goin' On. Still, Graham was a strong presence, making a huge contribution on hits like Smilin' (You Caught Me) and Runnin' Away, as well as the crushing slow-groover Thank You for Talkin' to Me Africa, from Riot. But the pressures spelled doom for the Family Stone. "I wasn't the first one to leave," says Larry. "I left in 1972, but it had started to deteriorate long before that."

The disintegration of the original Family Stone left the door open for Graham to form his own group, something he hadn't thought about until the Stone situation became too much to take. Even then, he wasn't interested in performing. He had planned to write for and produce a group he had assembled called Hot Chocolate, but renaming the band Graham Central Station, Larry went on to carve his own niche.

While Sly's success lay in his ability to meld deadly beats with unforgettable pop hooks, Graham Central Station's sound ran the gamut from ballads to doo-wop and excelled at over-the-top, take-no-prisoners funk. It seemed nothing made them happier than setting a groove loose. "When we wrote songs for Graham Central Station, we'd often start with the bass line. On Hair, for example, the drums were built around the bass pattern. And when we did covers, like our version of Al Green's It Ain't No Fun to Me, it would always sound like us, because I'd play the bassline in my style.

It's hard to imagine Larry Graham without his white, Japanese-built Moon custom bass. He designed it back in 1982, inspired by an old Fender Jazz he had used with Graham Central Station. That axe sported a body-mounted microphone that helped Larry to sing and play at the same time.

"We had to rebuild the mic after every show," says Graham's tech, David Hampton. "Larry would absolutely destroy it – sometimes before he even got to the performance. The microphone just couldn't take it." The Moon bass has Bartolini pickups and is strung with light-gauge GHS Bass Boomers. Graham runs his signal through a Morley Volume pedal with an A/B switcher, a Roland Jet Phaser, a Mu-Tron Octave Divider, and an old Morley Fuzz Phaser, which he first used on "Aint No Bout Adoubt It."

"A lot of people are fussy about the specifics of their sound," says Hampton, "but Larry's thing is just to turn it up until the stage rumbles. When it starts shaking, he knows he's got it right. It may sound simple, but that's his way of doing it – and there is only one Larry Graham."

The Power of the One, is available to buy or stream.

- Nick WellsWriter, Bass Player