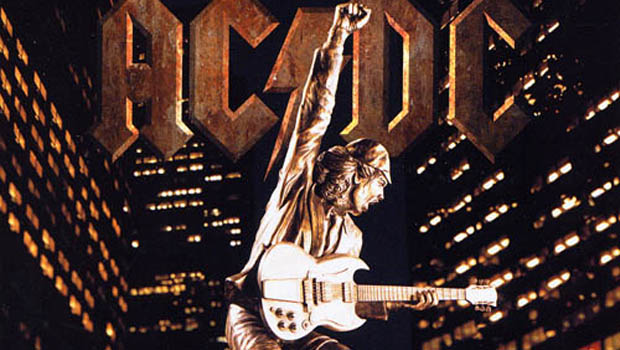

From the Archive: AC/DC's Angus Young and Brian Johnson Discuss the 'Stiff Upper Lip' Album

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Here's an interview with Angus Young and Brian Johnson of AC/DC from the May 2000 issue of Guitar World

In a world filled with change, there's something profoundly reassuring about AC/DC. They're like a James Bond film -- a winning formula, unvarying, but packed with loud noises, big explosions and stuff about busty lasses. You go in knowing what to expect and you're never disappointed. The boys are as ribald and rockin' as ever on their newest album, AC/DC's 17th to date. Never ones to pass up an opportunity for an oblique phallic reference, they've called it Stiff Upper Lip.

AC/DC's recipe for timeless rock is based on the fraternally tight guitar work and hookwise song craft of the brothers Angus and Malcolm Young. Angus' little schoolboy suit may be one of the oldest gags in rock, but there's nothing gimmicky about his straight-down-the-middle lead playing, or Malcolm's Rock of Gibraltar rhythms for that matter.

"There's more to playing the guitar than being able to split your legs," observes Angus in that cryptic, non-sequitur style of his that makes what he's saying seem nastier than it really is.

AC/DC came blasting out of Australia in 1976 and have shown no signs of slowing down ever since. Early recordings like Powerage and Highway to Hell, produced by Angus and Malcolm's older brother George and his partner Harry Yanda (both veterans of Sixties hitmakers the Easybeats), established AC/DC as a force to be reckoned with in the late Seventies. The band suffered a grave setback in 1980, with the alcohol-related death of their original singer, Bon Scott. But AC/DC soldiered on valiantly, drafting flinty-voiced singer Brian Johnson, who joined the band in time to make the all-time classic Back in Black album with legendary rock producer Mutt Lange. Johnson's bawdy workingman's style and malicious magpie vocal range have become an indispensable part of AC/DC.

The world would be a duller place without AC/DC anthems like "Whole Lotta Rosie," "Highway to Hell," "You Shook Me," "Dirty Deeds" "For Those About to Rock," "Thunderstruck," "Moneytalks" and "Hard as a Rock." Within days of its release, Stiff Upper Lip's title track jumped into the upper reaches of Billboard's Mainstream Rock chart. Sessions for the album, at Vancouver's Warehouse Studio, brought the band together once again with George Young, who was in the producer's seat for Stiff Upper Lip.

"With the three brothers working together again," says Brian Johnson, "it's just the climax of many years of doing the right thing with music."

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

GUITAR WORLD: Angus, how do you and Malcolm work together when you're writing songs? Who writes the lyrics?

ANGUS YOUNG: Well, Malcolm and me both. We bounce a lot of ideas between ourselves.

Who comes up with the double entendres? You've done "Stiff Upper Lip," "Big Balls," "Hard as a Rock"...

YOUNG: Some of them are staring you in the face. I think, with AC/DC, sometimes the most innocent thing can sound that way too. Somebody once said, "Thank goodness they never wrote Cats. Think what they would have called it."

So what’s "Stiff Upper Lip" really about, then?

YOUNG: It's an idea that sprung into my head when I was stuck in a traffic jam once. I was thinking that one of the earliest images of rock and roll that I'd ever seen was Elvis Presley, who always had that big old lip sticking straight up in the air -- that sneer, you know? And that's something that's carried straight through rock and roll. Hendrix, Jagger... they all had that thing with the lip. It carried over to the fashion world, too. Nowadays, models gotta get collagen injections in if they ain't got it.

When writing songs, do you or Malcolm ever try to sing in a high voice like Brian?

YOUNG: You mean try to imitate Brain? No. At that point we usually just ring up Brian and say, "Hey, we need you to come and yodel."

BRIAN JOHNSON: If they try to imitate me, they might end up looking like me. They wouldn't want that to happen.

Who does the best imitation of you, Brian?

YOUNG: What you do is, you get a truck and you drop it on your foot...

JOHNSON: Well, there are some good copy bands out there, you know. But the best imitation I've ever seen was by a chick, believe it or not, while we were in Vancouver recording The Razor's Edge. And she was pretty good.

YOUNG: You sure she wasn't doing something else to you?

What's the secret of that unmistakable vocal sound?

JOHNSON: Oh, there isn't any secret. When you're singing with AC/DC, it kind of comes natural. You get caught up in the enthusiasm of it all. Everybody's whackin' away 100 percent; if you don't join in, you may as well not be there. As Ang and Mal have always said, the voice can be like another instrument and contribute to the sound of the band. Rather than just being the guy in the front standing there like a big tart wiggling his hips.

Is there a favorite pre-show gargle?

JOHNSON: I'd love to tell you it's half a pint of Jack Daniels or something like that. But I'm afraid it's Perrier water. No, wait a minute; it's not even that. It's just regular water so I don't fart or burp when I'm up there.

The singing and playing on the new album gets into some very bluesy territory. The opening of "Stiff Upper Lip" could almost be ZZ Top.

YOUNG: From the first album, we've had songs like "The Jack" that are blues based. We also did it in "Ride On," where we went into the blues. Blues is a big part of rock and roll. The best rock and roll got its birth in the blues. You hear it in Little Richard and Chuck Berry.

"The Jack" has become a popular part of your concert repertoire, even in the States, where we don't have that particular term for venereal disease.

YOUNG: Oh, you don't have that?

Well, we have it. But we call it something else.

JOHNSON: What do you call it now? Sexually challenged?

YOUNG: "The Jack" is a song that came out of playing the pubs and clubs in the beginning. Bon would make references to a lot of people who had been his -- how do you call them? -- love companions for a while. Bon in his day had a bit of a reputation. I think it was his background. Because at an early age he was a crayfisherman.

JOHNSON: He caught crabs for a living!

Um, getting back to the blues tradition in AC/DC, it's nice to hear you guys do just a straight, bluesy three-chord rocker like "Can't Stand Still."

JOHNSON: Aye, that's one of my favorites. I don't think I've heard anything like that played that well before. It just gets me all goose bumpy every time I hear the flippin' thing.

I love the ending on that one. You really schmaltz it up.

YOUNG: That's what happens sometimes. Every time we'd go in and cut a track, Brian was singing along with us for the vibe. And on that one he was really hammering it out. We were getting off on watching him do it. Everyone was having a little fun with it. So when it came to the ending, everybody sort of downed tools and gave him a little ripple.

Somebody yells out "take it home," I think.

YOUNG: Oh, yeah, there was lots of yellin' and whistlin' and a'hollerin.' That's what makes the atmosphere, you know.

So AC/DC still cuts basic tracks in the time-honored way -- live in the studio with the whole band?

YOUNG: Yeah, everything. We all get in there. That's what makes rock and roll. You lose that when you start separating everything up. You can separate things technically by isolating your amps, but when we're in there recording, we all like to be together so we can all communicate easily.

And then once you get the basic tracks, you and Malcolm might add a few guitar overdubs?

YOUNG: Yeah, if Mal has a little added rhythm part, or if I have a lick here or there that'll make it different. Or we might just use the basic track. Whatever gives it the best atmosphere.

Was your choice of guitars and amps on this album the same as always?

YOUNG: Absolutely. Mal still has his Gretsch Firebird, and I played my '68 [Gibson] SG -- the one I've always had, ever since I was young. I've got to look after it more these days.

GW: You played a '64 SG on Ballbreaker.

YOUNG: Yeah, I've got a few different ones. For the bulk of it, though, I do try to use the '68 ones.

What about amps?

YOUNG: Marshalls. The old ones. Mal likes a big, clean sound. He doesn't like it if distortion starts creeping in. He likes to get as big and fat as possible without that.

And you're a little grittier.

YOUNG: Yeah, well, I've always viewed myself as that. Even when I was younger, working with Mutt Lange, I'd say, "Maybe I should clean it up." And Mutt would say, "No. Actually if we can drive it a little bit more, it'll smooth out."

AC/DC is one of the ballsiest bands Mutt Lange ever produced.

YOUNG: Well, his first big mainstream success in America was Highway to Hell. I think he was a little shocked himself. He said, ''All these years I've been working on all that nice stuff, and here come these colonials."

JOHNSON: Him being a colonial himself, the cheeky twat. He's from Zimbabwe, you know.

Well, you guys are certainly ballsier than Shania Twain.

JOHNSON: Oohh, I don't know...

YOUNG: He's talking from the waist down.

JOHNSON: Yes, absolutely. My mind's always in my scrotum.

And that's why we love you guys.

YOUNG: I remember Mutt saying that, of all the many albums we'd done with my brother George and his partner, Harry Vanda, the one Mutt wished he would have done, where he was envious of George, was Let There Be Rock.

Stiff Upper Lip is your first time working with George since Who Made Who in '86, right?

YOUNG: Pretty much so. But every album we've ever made, whether George was producing or not, we've always sat down with him and played him the material, either before or during the recording. He gives us a good idea of where we're at.

JOHNSON: But this is the first time George has produced one of our albums by himself. In the past he's always worked with Harry. Not detracting from Harry, but it was kinda streamlined this time. You had no one to answer to or discuss things with except Malcolm or Angus. We were working pretty hard this time actually, from about 11 in the morning until one the next morning sometimes. Saturdays as well. It was good, though. George always had a game plan. I hate it when you're hanging around waiting for the next decision. George always had it all worked out.

In a lot of groups, it's a tense situation if you have even two brothers in a band -- like the Gallagher boys in Oasis.

YOUNG: I wouldn't call them a band. [laughs] I suppose maybe in the modern sense. You look at the two Kinks, Ray and Dave Davies. I think they're a better example.

So how do you and Malcolm and George get on?

YOUNG: Just fine, really. I've actually got more brothers. All together there were seven boys in the family.

What do you say, Brian? Is there a lot of sibling rivalry?

JOHNSON: Not really. What I love is sometimes Mal or Ang will look at George and just go "ummm," and George will go "hmm." And they've just had a conversation. Words don't get in the way of their communicating. I think the boys believe in George more than anybody else in the world. They trust him. Shit, I do. When it comes to rock and roll, the guy really knows what he's talking about.

Let's talk about the song "Safe in New York City" from the new album. Do you really feel safe in New York City?

YOUNG: I suppose that song is a little tongue in cheek. Last time I was in New York, that's all people were talking about: how safe it was, how it was gonna be such a great place to live. For me, New York has always been a city of unpredictability. You can never guess what's going to happen next.

JOHNSON: The lads had a bit of fun with that song, 'cause in the end they stuck in that little line, "I'd feel safe in a cage in New York City." Just in case people start fuckin' believing it.

A lot of people wonder where some of those AC/DC songs come from. Like "Whole Lotta Rosie." Was there really a Rosie?

YOUNG: There was, actually. I remember we were playing in Tasmania. And the capitol of Tasmania is Dar Es Salaam. Bon had gone out one night after we'd been playing. He'd just been wandering the streets around the little club areas. And he was walking past this street and this girl grabbed him from a doorway. She pulled him in and said, "Hey, Bon, in here." And he thought "Hey, why not?" The girl was there with her girlfriend, and he spent the night. This girl who was with Bon, she was a fair size girl. I mean they didn't have Weight Watchers then. She said, "Bon, these last few months I've been with 28 famous people." And she was giving him the lowdown of politicians and different people she'd been out with and whatever. Anyhow, the next morning Bon woke up sort of pinned to the wall. The girl thought Bon was still sleeping. She leaned across to her girlfriend, who was sharing the room, and she said, "twenty-nine." Her name being Rosie, Bon thought it was a great title for a song. He said this girl was worthy of being put into a piece of poetry.

Was there ever any thought of packing it in when Bon died?

YOUNG: We didn't really know what we were going to do. We had been writing material, and my brother said the best thing to do, to take our minds off of everything, would be just to keep working on the song ideas that we had. Then we could at least say we'd finished what we started. And at some point we knew that we would need somebody strong to sing these songs. And we were lucky. When Brian came in, he had big shoes to fill, and he's given it his own unique character. So we've gone forward. It was a tragedy, but a whole new thing came out of that.

Does one have to summon up a bit of nerve to write a song like "Can't Stop Rock and Roll," from the new album? Do the words "rock and roll" mean anything anymore?

YOUNG: That song is our little statement on that. Over the years, you start seeing more and more pundits in the world. I mean, they've got experts for everything now. Everywhere I went, I would see these commentaries. And it would always be these sweeping statements like [fatuous American accent], "Well, rock music's dead, and dance music's saving the industry... "

JOHNSON: And so the song opens, "Don't you give me no line..." It's true.

YOUNG: Rock music has been around since the days when Chuck Berry put it all together. He combined the blues and the country and rockabilly and put his own poetry on top, and that became rock and roll. And it's been hanging in. Our whole career has been playing rock and roll. And I'm sure you still get a lot of people tuning in to bands like us and the Stones. And younger bands will be plugging into it and taking it into the next realm. There's always going to be another generation that will take it and give it to a new, younger audience. So I think it will just keep going on.

Considering that we now have bands like Marilyn Manson and Nine Inch Nails, is there any place where the Bible thumpers are still scared of AC/DC?

YOUNG: Oh, you still see a few people quiver.

JOHNSON: I'm sure they think we started it off. I'm sure they think it was our fault.

YOUNG: But I think that's been around since rock and roll first turned up.

JOHNSON: "Don't let Elvis show his hips on the television, 'cause it will drive everyone mad."

YOUNG: The English did that to me the first time I was on one of their shows. The producer said, "Don't put the camera on his hips. We know what he does with them."

When AC/DC is on the road, is it more like an army on the march, a traveling circus or a roving band of pirates?

YOUNG: You mean do we come to rape and pillage?

JOHNSON: A roving band of pilots?

Yeah, that's it. Aviators run amok.

YOUNG: Well, when we finished making our record, we left Vancouver exactly as we found it.

JOHNSON: We got our deposit back. We're not too bad, really. We made more friends than enemies. Put it that way.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.