The pentatonic scale is the most important scale for guitarists – and these 40 licks will take your rock and blues chops to the next level

When it comes to the guitar, the pentatonic is the one scale to rule them all, and despite its ubiquity, the possibilities are limitless – as our deep dive tab and video lesson demonstrates

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It’s unlikely that many would disagree with the notion that pentatonic scales are a guitarist’s best friend. Used in every genre of music and countless songs of the past 70 odd years, it really is as versatile as it is valuable.

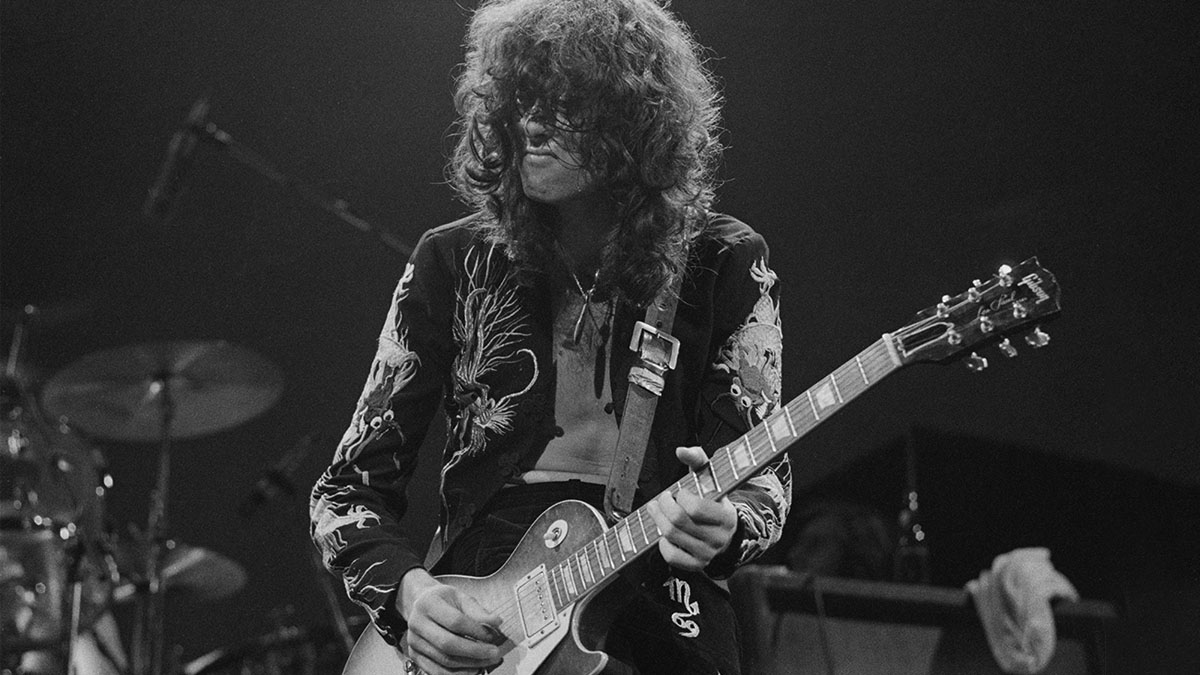

Its handy two-notes-per-string layout and uncomplicated musical application has made it the perfect choice. Whether it’s Jimmy Page crafting riffs, Gary Moore blazing or Eric Johnson improvising over vast instrumentals, the pentatonic is there as a foundation, the main ingredient, and the secure footing for great players.

The name of the scale comes from the Greek word ‘penta’, meaning five, and ‘tonic’ referring to tones, so it’s easy to discern that we are dealing with a five-note scale. Viewed simply, we are taking two notes away from the major scale, avoiding the semitone intervals and leaving us with a scale that is rather user-friendly, as each note will sound good (although some will sound better than others) over the diatonic chords in a given key.

There are no ‘avoid’ notes. This gives us a great way in to improvising as we don’t need to worry too much about hitting certain notes over each chord, or ‘playing the changes’ (although we would always advocate doing so, where possible).

The major pentatonic intervals are R-2-3-5-6, while the minor pentatonic’s are R-b3-4-5-b7, often presented in five positions across the neck, following the CAGED system (each of our examples follows these positions). Get these memorised as a priority to unlocking the fretboard.

Once you have done this, it is important to see each note as an interval in relation to the root. Learning to identify all of the 3rds or 5ths in a pentatonic scale, for example, will mean that you can target each of these when improvising, leaving out any element of guess work as well as allowing for more confidence when changing chord or key.

Of course, any scale is to music what the alphabet is to language. Yes, it’s fundamental that we know it, but using it is a different story. As with language, nothing beats practice along with careful study of those who can already communicate, so finding the elements that make great players sound so good is pivotal.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Phrasing is key, so experiment with rhythmic patterns, space, intervalic jumps, and expressive techniques such as string bends, slurs, and vibrato. This is where the scale can be transformed from a simple pattern into beautiful melodies and cool riffs.

As always, we would encourage you to use these examples as a platform to build on, taking various elements and using them to develop your own ideas and licks.

Get the tone

Amp Settings: Gain 7, Bass 5, Middle 5, Treble 6, Reverb 4

You will hear a variety of tones throughout these examples. I switched between a Strat and a Gibson ES-335, mostly played through a Marshall-style guitar amp with various overdrive pedals. Use your ears to get to something that you think is appropriate (although too much gain is never advised when learning), and dial in some reverb and delay to taste.

Example 1. Five licks in E minor

Notice how certain devices are used to help these licks sound musical. The rhythmic repetition in bars 1-2 or 12-13, for example, gives these bars a call and response feel.

The triplets in the fourth and fifth licks add interest and create the feeling of speeding up and slowing down, or different ‘gears’. We also have some ‘blue’ notes (b5 = Bb in E minor) in the last bar which, although not strictly in the pentatonic, can be added with some subtle semitone bends.

Example 2. Five licks in E major

This example uses lots of slides and slur combinations which, when paired with string bends, give the licks a vocal-like and expressive quality. There are a couple of rake and slide combinations in bars 10 and 24 (a favourite technique of Gary Moore). These can be tricky and require some accurate timing so practise these in isolation, slowly at first, until you are comfortable with this technique.

Example 3. Five licks in G minor

Here’s a funky blues in G minor. There are a number of runs that use triplets over the eighth-note based backing. Some of these licks may need to be practised slowly to ingrain the muscle memory, especially in less familiar positions.

Pay attention to the hammer-ons and pull-offs as these will make the licks sound better – and easier to play! Notice how the line in bars 3-4 is based on a 4th interval. Experiment with different intervals to create different sounds.

Example 4. Five licks in G major

Several times in these examples you’ll notice the G major triad, which lives inside the major pentatonic, being used to create melodies over the G chord. This can be especially effective as it clearly outlines the underlying harmony.

The wider intervals of 5ths and 6ths in bar 13 can be a useful device to add a different sound to your licks. Also watch the string skips in bar 25 as these can be tricky at faster tempos. If you love 16th note phrasing as here, Eric Johnson is your man!

Example 5. Five licks in A minor

We need a little more energy for this one as the pace has picked up a bit. Be sure to attack the strings with a bit more attitude to get the correct feel, without compromising on the bending intonation (especially on the three-semitone bend) or vibrato, which is a bit faster here, although still fairly shallow in the classic rock vein.

We see an open fifth string in bar 15, which can be an interesting way to add something a little unexpected, as long as the key allows.

Example 6. Five licks in A major

All the licks here include space and leave pauses between phrases. This allows the listener time to digest each idea and makes everything sound more musical than an endless stream of notes.

Some notable musical devices to note are the pattern in bars 18-19 which uses a rhythmic and melodic motif, as well as the phrases in 21-22, which are essentially the same idea but moved to a different string set and rhythmically displaced to a different point within the bar.

Example 7. Five licks in D minor

Here’s a shuffle blues in D minor. We see some repetitious pentatonic patterns put to use, reminiscent of Gary Moore and Eric Clapton. These rely on muscle memory so practise slowly to get the patterns under your fingers.

Lick 4 falls in the fourth shape of the scale, but notice how it ducks down into shape 3 in bar 19 (very Jimmy Page). This gives us different phrasing sounds and can make things easier to play, so experiment with your own licks that cross positions.

Example 8. Five licks in D major

These examples include rhythmic motifs and syncopation to create interesting and melodic lines. Pay attention to the rhythmic shape to execute these licks correctly.

The final lick has some interesting intervalic elements which are worth exploring and can break up the tendency to run up and down the scale in a too familiar way.

I hope you take some of these ideas and incorporate them into your own improvising. Good luck!

David is a guitarist, producer, and educator. He has performed worldwide as a session musician, with artists and bands spanning many musical genres. He draws upon over 20 years of experience in both live performance and studio work, as well as numerous composing credits. As a producer, he's collaborated with artists across genres, including pop, RnB, and neo soul. David holds a master’s in jazz guitar and teaches at BIMM London and the London College of Music. He is also a regular contributor to Guitar Techniques magazine, sharing his love of blues in a monthly column.