Bring a new level of rhythm and groove to your guitar playing by incorporating walking basslines

An in-depth look at how to bring the goldmine of jazz bass into your guitar playing

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There are few things in music more satisfying than a perfect walking bassline. In this lesson we explore the sounds of classic jazz walking bass, learning how to adapt the ideas to the fretboard and use them for new harmonic-melodic inspiration.

Most of us get ourselves further into jazz by transcribing lead lines or learning more chord extensions. While these are both fantastic methods, which I fully endorse, they have their drawbacks. It takes a while to fluidly incorporate complex chords into our improvisation, and solo lines leave us particularly exposed if we fall off and lose the changes - not to mention the various challenges of syncopated, stop-start phrasings.

I actually think walking basslines are the quickest way you can get to grips with the underlying harmony of a new jazz tune

Whether you’re an aspiring jazzer or just want some new grooves, try incorporating the eternally satisfying world of walking bass into your practice routine. Walking lines are a sort of musical crossover point, combining harmonic structure with melodic direction and subtle rhythmic inflection, and so making highly efficient learning material.

I actually think walking basslines are the quickest way you can get to grips with the underlying harmony of a new jazz tune, at least in the basic practical sense of being able to hack it through unfamiliar changes without losing the flow too much. And if you’ve listened to a fair bit of jazz then you’ll have half-consciously picked up many of the stock phrases already.

Although...I’m not sure why I’m trying to persuade you with words when I could just play you some great walking bass. Listen to Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen (the ‘great Dane with the neverending name’) walk behind pianist Oscar Peterson, guitarist Joe Pass, and violinist Stephane Grappelli in How About You?

What are the principles of good walking bass?

As mentioned, strong walking bass combines the rhythmic, harmonic, and melodic. My bass-playing friends (and the best of the web’s instructional materials) are in broad agreement about three key principles of effective bassline construction:

Guard the groove above all else - Jazz drum patterns, full of offbeat fills and sharp interjections, tend to be more syncopated than the basslines that accompany them. This often leaves the bass as the main pulse of the music, on which the rest of the group rely as their anchor. It must give a reliable foundation for the overall rhythmic flow.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Walking lines should make independent melodic sense - Ever noticed how quite plenty of jazz bass solos are pretty much just the bass doing what it was doing anyway, but with the rest of the band laying out a bit? This is a central principle of walking basslines - they should sound good as they are.

Aim to create deliberate melodic direction, singing inside as you play. In the words of low-end legend Christian McBride, “make sure it’s linear... [and] doesn’t jump and skip around a lot... if you want to break it up a little, make sure there’s a pattern inside what you’re doing so it makes sense”.

Don’t be afraid to get rough and percussive - As we will see, walking basslines have their ultimate origins in the proto-jazz of the pre-amplification era. As such, the style has been intensely physical from the start, with early bassists employing a variety of striking and slapping techniques so as to be heard above their bandmates. String slack and percussive body resonances have always been integral to the sound of the double bass, often taking precedence over the finer points of intonation.

We should never sound clinical - even a smooth-toned electric bassline should sound like it’s being played by a real instrument (in my old office job I couldn’t help but notice how this imperfect, humanized feel is a core separator between good mellow jazz and the horrifyingly soulless muzak found in corporate elevators...).

So how do we apply this to the guitar?

When getting stuck into any non-guitaristic style, it can be useful to conceptualize your learning into two areas - playing the right notes, and playing the notes right. While of course deeply interconnected, thinking in these bifurcated terms helps us quickly summarise the basic elements of any new music. Here, we will apply this approach to the construction of walking basslines on the guitar.

Playing the right notes: How do we choose which tones to use?

First up, why do we call it walking bass in the first place? While the exact etymology is somewhat unclear, it has stuck for obvious reasons. Walking basslines are two-sided, roughly alternating between consonance and deviance to match the regular, offbeat feel of the drums.

All so-called musical rules are of course regularly broken to great effect. But a few things hold up pretty consistently here. Put simply, aim to play ‘chord tones’ on the beats 1 and 3, and create tensions with other tones on beats 2 and 4. Watch bassist, composer, and deserving YouTube celebrity Adam Neely’s superbly concise rundown of how this works in action. See how many of the phrase patterns you recognize already:

Chord tones are, as you’d expect, the essential notes of the underlying chord, typically the root, 3rd, 5th, and 7th. The 6th is also an honorary chord tone, mainly because it lies a 3rd below the root, a strong harmonic relationship (we’ve all learned the boogie woogie bassline). Much of walking bass fluency comes from being able to coherently link chord tones at will.

Including the root is particularly important, or else all chords played by the ensemble will effectively be inversions of themselves (as the lowest note in the group will almost always come from the double bass). Jazz guitarists tend to leave our own chord voicings rootless in group to avoid cluttering up the sound, and pianists often do similarly... so it’s up to the bass to provide the foundations.

Non-chord tones can be used to create colorful tensions on beats 2 and 4 that push the music forward (most non-root chord tones also work well). Aim to create coherent flow, sampling from a variety of methods, some of which are explored in the example below. In fact, if your phrases are concisely pointing to the right place then you can get away with almost anything.

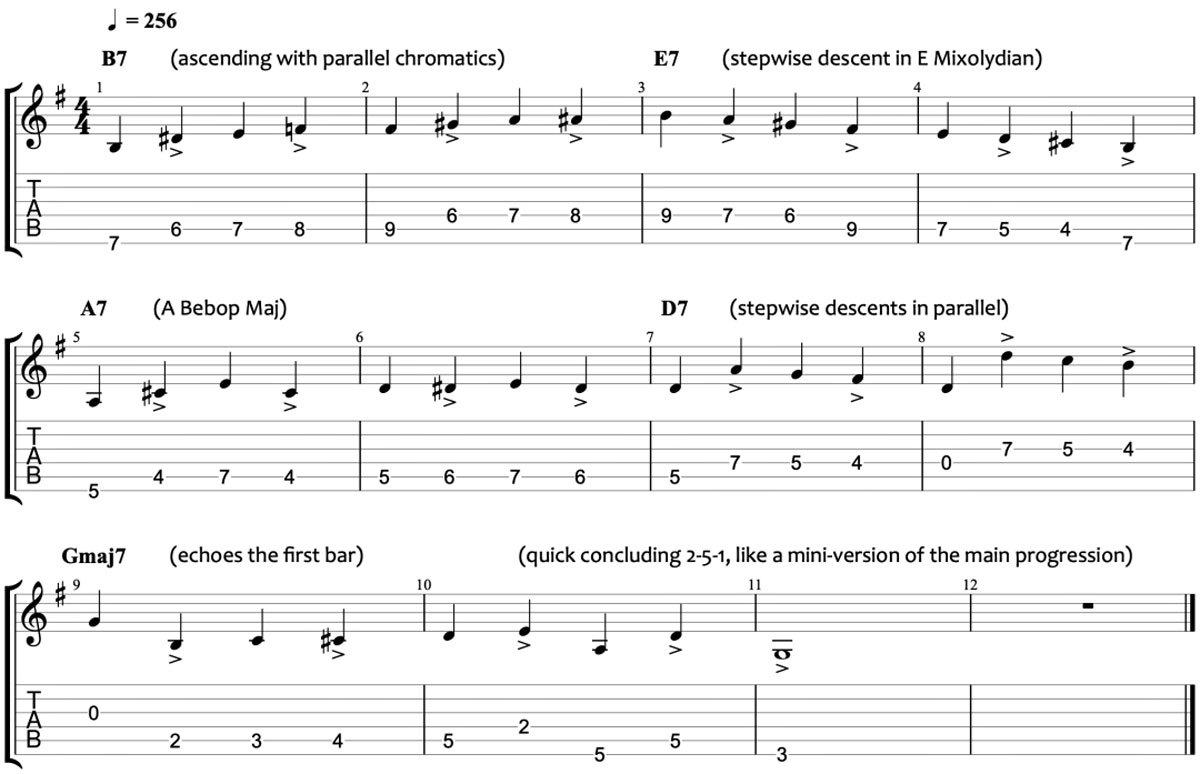

Exercise 1: Stock phrases over cycling dominants

This exercise showcases a few widely applicable melodic walking ideas (cliches). We follow the progression of the Rhythm Changes bridge, which sees dominant chords modulate up a perfect 4th each time (equivalent to moving backwards through the cycle of 5ths) before resolving to the root major. It’s a kind of harmonic meeting point between jazz and blues - basically, moving down a string like the first change in a 12-bar, but 4 times in a row. You’ll recognize it already.

We’ll explore the physical/technical side of things in the next exercise. This is about the notes - for now, just go through and get into the flow, practicing in isolation and with the backing track. Shuffle things up, refit the idea from one bar into others, etc.

Think about how each note functions in relation to its underlying chord (some of the key ideas are explained in the annotations). In particular, note the flexibility of the Bebop Major scale (1-2-3-4-#4-5-6-7), and see how the 6th can be used as a chord tone for majors and dominants alike, meaning you can often use the same shapes over both (e.g. bars 1-2 vs. 9-10).

Here are three backing tracks to use for these (and the other) exercises - at 130, 220, and 256bpm:

Try coming up with your own lines over the backing tracks, guided by the following formula. Don’t be afraid to break the rules either - if you study the great basslines from jazz history you’ll find all sorts of weird and wonderful deviations. But as a starting point, get familiar with this as a sort of safety approach:

- Beat 1: Play the root

- Beat 2: Play a scale tone

- Beat 3: Play a non-root chord tone

- Beat 4: Play an approach tone to the next root

On the final beat, we have a few choices for creating anticipatory tension:

- Dominant: Play the 5th immediately above the next root

- Diatonic: Play a neighboring scale tone to the next root

- Chromatic: Play a half-step up or down from the next root

There are countless ways to give your lines shape, structure, and direction. In fact, some of the core methods are close to those found in Baroque counterpoint textbooks, such as Johann Joseph Fux’s hugely influential Gradus ad Parnassum, published in 1725. Here are a few of the most important ones:

- Arpeggiate the triad: 1st/3rd/5th combinations are the foundation of Western harmony, giving a rangey, spacious feel, full of momentum.

- Play through the scale: Using scale tones in order (stepwise motion) gives a natural, even flow, but gets predictable quickly.

- Ascending 4ths/descending 5ths: moving in these patterns will give a robust, architectural feel. Try outlining some 2-5-1s (e.g. the final four notes of the study above).

Playing the notes right: How do we bring these melodic patterns to life?

To capture the feel of the double bass, we should examine the physical quirks and characteristics of the instrument itself. Around since at least the 16th century, its exact origins are shrouded in mystery - there is debate about whether it evolved from the violin or the viol, a near-extinct cello-like instrument with movable frets.

Like guitars - but unlike violins, violas, and cellos - basses are usually tuned in fourths. In fact, standard tuning for bass (on both upright and electric) is just the EADG strings of the guitar, but an octave lower.

Similarly, steel strings are often used on both instruments. But it is the dissimilarities of the bass that we should be most interested in, as they’ll be what we’re missing in our own sound by default. Most importantly:

Scale length: Coming in at over a meter, the scale length of the double bass is about 70% greater than that of a Stratocaster. This makes position shifting tough, meaning bassists are adept at avoiding unnecessarily wild physical jumps.

Passages with wide shifts can almost be like a dance with the instrument, requiring movement of the full upper body. Open strings are used commonly to counteract these difficulties, giving a short break to move position.

Frequency range: Not all octaves are equal - our brains interpret lower tones differently. As a general rule, the lower a tone is, the less our ears perceive it as being melodic (as opposed to textural, rhythmic, etc).

The same interval will feel more dissonant the higher up we hear it, effectively meaning that you can get away with a bit more chromatic weirdness on the bass as long as there’s a good overall flow. Similarly, the intonation doesn’t have to be quite as perfect.

Sonic physicality: Anyone who’s stood next to a live upright bass (or a subwoofer) knows that basslines are embodied, physical phenomena. You can feel the air moving in a way that just doesn’t happen higher up.

This isn’t a surprise, given that the lowest note on a double bass (E1) has a wavelength of over 8 meters, coming in at around 40Hz - only an octave or so above the lowest limits of our hearing. (Anything less than 20Hz - 20 cycles per second - starts becoming a sequence of distinct sonic events, devoid of harmonic properties).

Picking technique: Jazz bassists tend to use a unidirectional picking approach. Basically, almost everything is an upstroke, played near the tip of the fretboard using either the index or index-and-middle fingers. Most are rest strokes, pushing through the string and stopping on the one above.

Rhythmic articulation is hugely important - each pluck should be weighty and confident, and the strings are often slapped against the fretboard, introducing a percussive ‘micro-delay’ before the next note. Various ghost notes are employed, and the open strings bring a distinctive resonance when hit hard, with wide oscillations that buzz against the neck (almost like an Indian tanpura drone).

Applying bass quirks to the guitar

A key principle of learning any non-guitaristic style is that we don’t have to replicate the new sounds and shapes exactly - we should aim to bring out the strengths and particularities of our own instrument as well. Here are some ideas for finding an effective balance:

Aim for an even picking approach:

Several methods can work, so try out different ones and listen to the results with an open ear. I sometimes like to use a super-thick gypsy jazz plectrum for walking on the acoustic, and large, inflexible jazz picks for the Strat - longer plectrums give you more margin for error, making it easier to really dance across the strings with rhythmic freedom.

I usually drop in plenty of economy picking in my general improv, but when walking I tend to stick strictly to up-down-up-down alternation, with the downstrokes on 2 and 4 being slightly accented - having a consistent pattern evens out the groove (down-up... works too). Listen carefully to the kick drum, which lies in a similar part of the frequency spectrum to the bass, and be careful not to drag (play behind the beat) on the last note of the bar.

Feel the rhythm with your whole arm:

Keeping things loose to avoid overstraining yourself. You can accentuate the offbeats a little by tapping your foot, nodding your head, or setting a metronome to hit on the 2 and 4. And remember, it can all be a bit messy as long as the groove is there.

Try out actual double bass techniques too:

They aren’t always ideal for the guitar (particularly the electric), but you should see how they affect your melodic thinking and the sound itself. See what the bassistic rest stroke with index & middle method does to change your mindset.

A happy medium between guitar and bass technique might be to play everything as rest strokes with the thumb, which also allows for some good fretboard slap. But it can take a while to speed up.

Also, bassists don’t tend to use the fretting hand ring finger very much (a principle popular since Czech bassist Franz Simandl’s 1881 work New Method for the Double Bass).

So try playing octaves and other wide interval jumps with the index and pinky, and sticking to the index/middle/pinky combo overall. For more detail see Ari Roland’s Tips for building your walking bass demo, as well as Adam Neely’s How to play bass for guitarists and Make your electric bass sound like an upright videos.

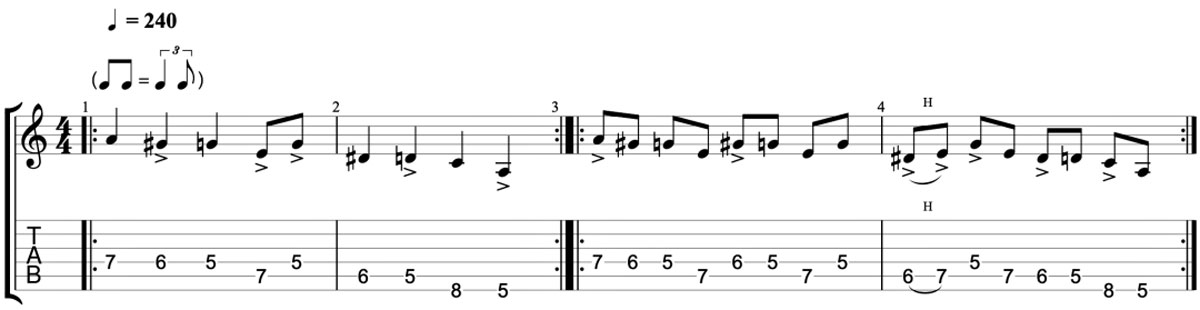

Exercise 2: Translating walking bass inflections to the guitar

The following exercise explores a few ways to recreate some bassistic inflections. It crams in quite a few ideas - in reality, I’d suggest ornamenting much more sparsely than this (it’s hard to make frequent ornaments flow unless you really know the drummer). It features 8th note doubles, hammer-ons, sliding grace notes, mini-sweeps, and liberal use of the open strings.

Learn to pepper your walking lines with your favorite inflections, practicing at different speeds. It takes some work to incorporate them into a steady alternate picking flow - try sticking to an alternating pattern on the main beats, and fitting the inflections in however you can around this. I’ve noted down how this can work for the first line (v = upstroke, n = downstroke):

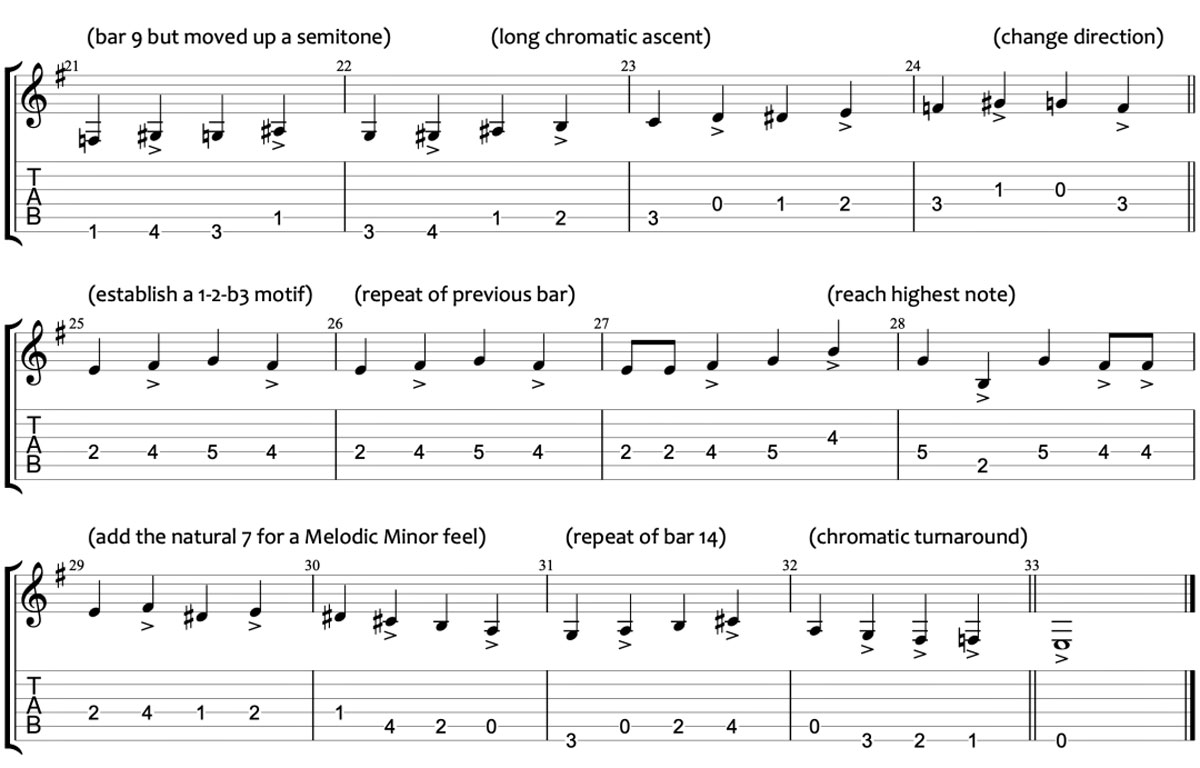

Exercise 3: Expanding walking lines into solo licks

You can also unpack the rough movements of quarter-note walking lines into fast eighth-note runs, helping bridge your bass phrases with your lead line playing. For example, here’s one way of doubling the quick chromatic descent from bars 4-5 of the last example:

Brief origins of jazz walking bass

Regan Brough, writing in the Online Journal of Bass Research, summarizes what is known about the origins of the walking style. “Due to the inability of engineers to record the bass prior to 1925, there is difficulty pinpointing when walking bass lines originated... [They were] refined and honed through the contributions of various bass players in the late 1920s. Many early bassists doubled on tuba; it in turn influenced their approach."

He adds that pre-1930s basslines often used the bow, and when plucking techniques did come in they tended to be much more percussive than today, mainly to compensate for poor microphone quality. Walking bass emerged into its own right over the 1930s, heavily influenced by the dance rhythms of New Orleans.

Some key early innovators to check out include Walter Page, Pops Foster, Bill Johnson, Steve Brown, John Lindsay, and Milt Hinton. Recommendations for more recent players are at the end.

Exercise 4: Modal jazz combination study

Now, we will apply all aspects of our learning to a full 32-bar chorus, covering a range of flexible walking concepts. It follows the sparse, wide open changes of John Coltrane’s Impressions - a tune that exemplifies modal jazz, a sub-stream where musicians pause on each chord for extended periods, without much functional harmony dictated by the score. In essence, it’s music designed to for stretching out.

Impressions, heavily influenced by the longform ragas of Hindustani classical music, is perhaps the defining uptempo modal composition (...and if you slow it down a bit then you have the changes for the canonic So What?). Aim for a fast-flowing, hypnotic groove. And if you have a loop pedal, lay the bassline down, add percussive stabs on 2 and 4, and solo over it (this provides deadline-challenging levels of enjoyment).

See how you can use the ideas above to deepen your harmonic understanding and enhance your broader playing. There are great free backing tracks on the web (see Learning Jazz Standards on YouTube), but I’d definitely recommend shelling out for iRealPro too (used for the backings here) - it’s incredible software for anyone learning jazz, with thousands of customizable charts.

And always be open to trying some wider changes - eg, you can down-tune the whole guitar, perhaps lowering everything by a tone or so. Slacker strings can give a fantastic looseness on steel-string acoustics, and for a bassier resonance you can put some flatwounds on the E, A, D, and maybe G strings.

And to hear basslines more clearly when transcribing ensemble music, turn the low-end up on the EQ settings of your iTunes/Spotify/speakers.

You could buy an octave pedal too, which gives you access to the full bass register. Or maybe even pick up a cheap electric bass. Continually experiment with different ornamentations, and practice humming your walking lines while actually walking around (your footfall is probably in the 100-130bpm range). Mainly, just have fun with it - there are few more dependably satisfying areas of improvisation.

George Howlett is a London-based musician and writer, specializing in jazz, rhythm, Indian classical, and global improvised music.