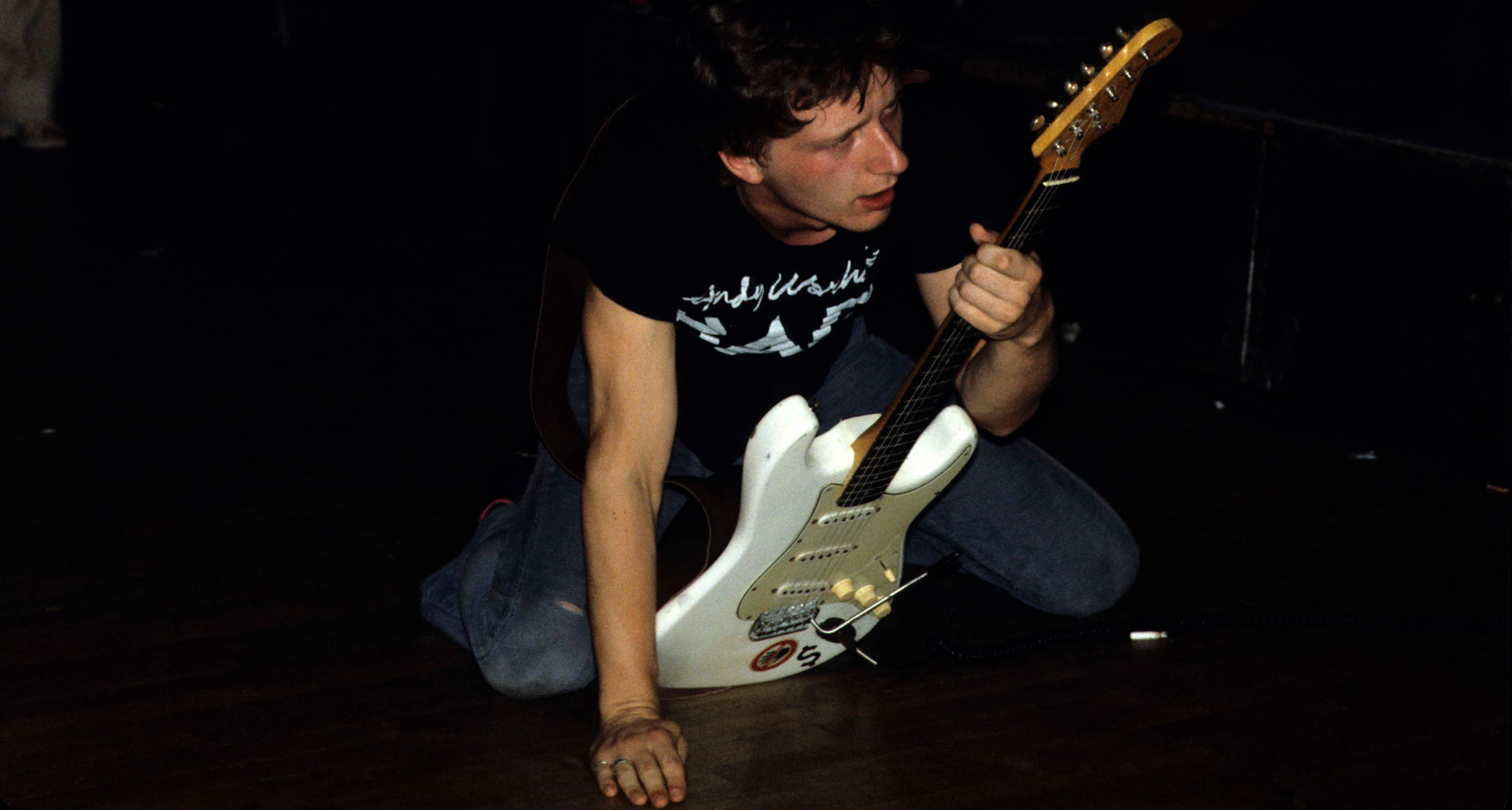

“Squeeze’s Glenn Tilbrook knows a thing or two about using inventive and interesting chord voicings”: How you can swap the notes in a chord to give it a different feel

A lesson in second inversions sounds like advanced physics but it's simply swapping the root note for the 5th, expanding your chord vocabulary with a minimum of fuss

When we learn about creating a chord from a scale, we list the notes in order of appearance: Root, 3rd, 5th.

However, swapping this order around can sometimes be really effective. Shifting the 3rd (or b3) to the bottom gives what classical composers call a ‘first inversion’.

This time around we’re going to move the 5th to the bottom, making a ‘second inversion’. It’s still the same chord, but the emphasis shifts from the Root and gives the chord a slightly different feel.

For example, play a regular C major chord and follow up with a G major. This is all fine, of course, but maybe there’s more we can do with it… How about using a second inversion for that C chord?

In practice, this means swapping the 5th (G) to lowest note instead of the Root (see Example 1 below). These days, we’d usually call this C/G – and it really sets us up in a grand way for that G chord.

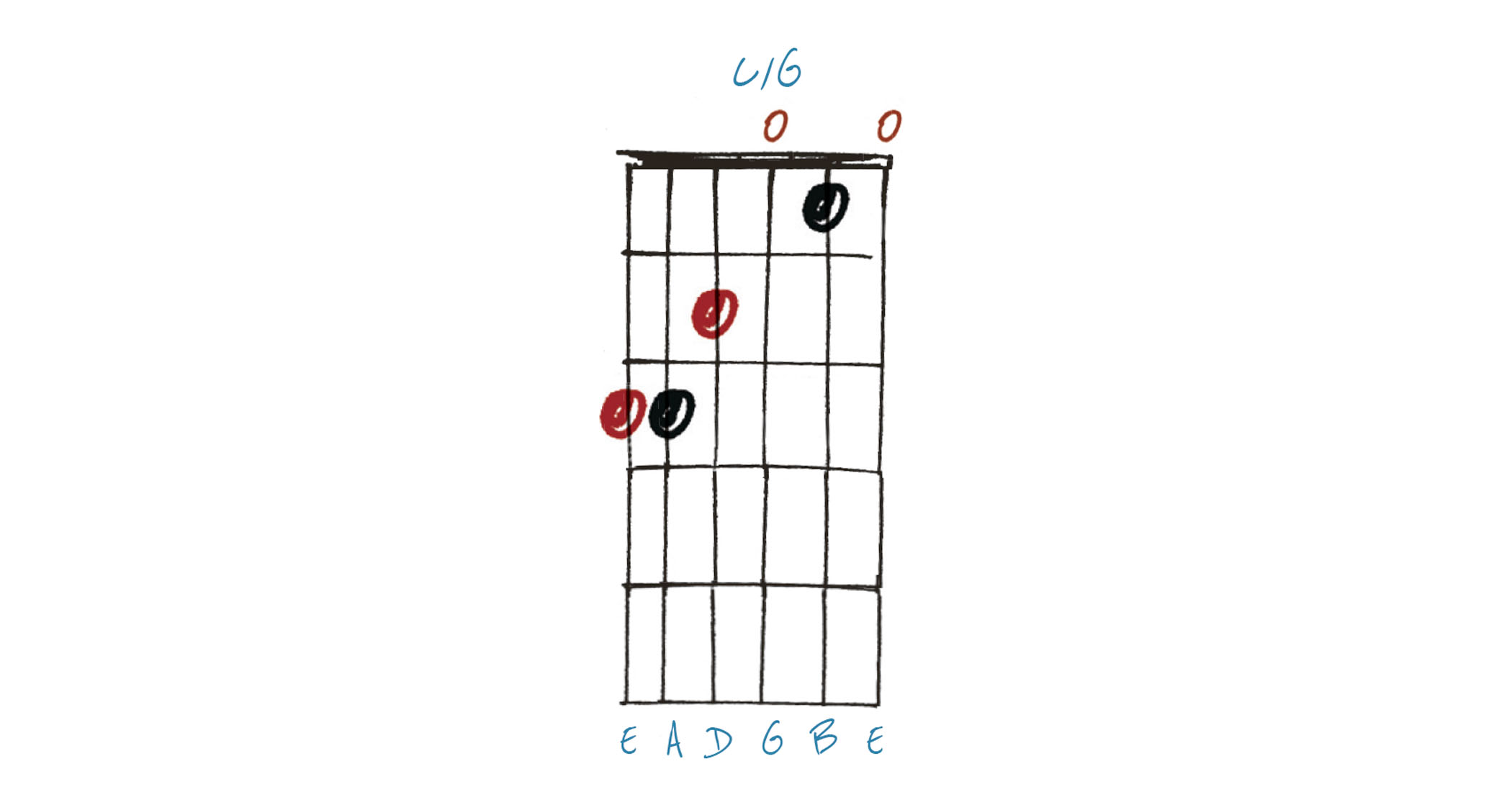

Example 1. C/G

This is a C chord with the 5th (G) on the bottom. Its ‘official’ name would be C (second inversion), but you’ll usually see it referred to as C/G – a slash chord.

This is worth experimenting with in the context of a chord progression: for example, before a standard G chord. Hear it in action on Pulling Mussels (From The Shell) by Squeeze.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

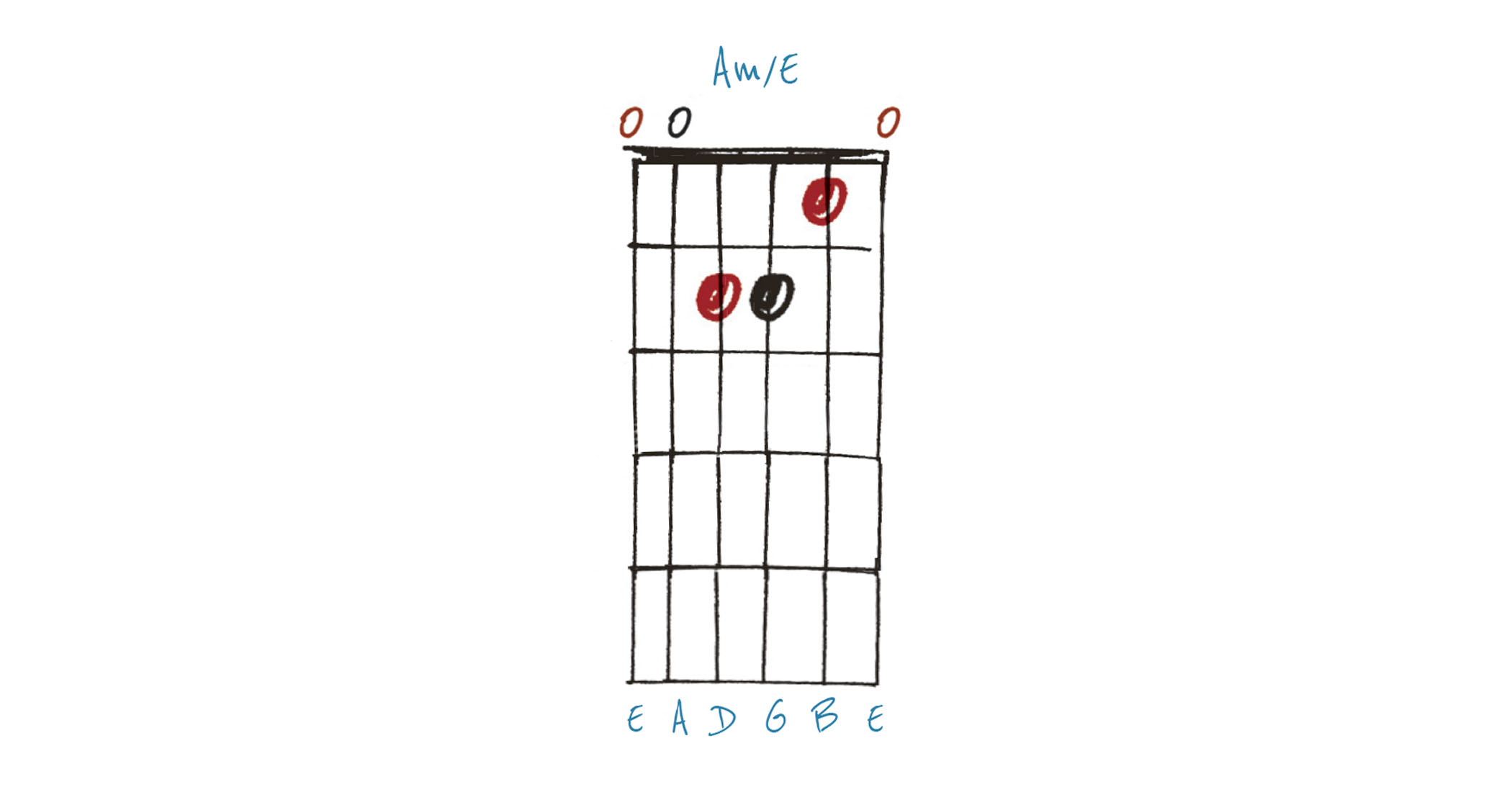

Example 2. Am/E

The inversion/slash chord approach can be applied to minor chords, too, as demonstrated by this Am/E (aka A minor second inversion).

This leads beautifully into a standard E major, or maybe try a D major first inversion (D/F#). You could potentially expand from here to form a counter melody in the bass – like Bach!

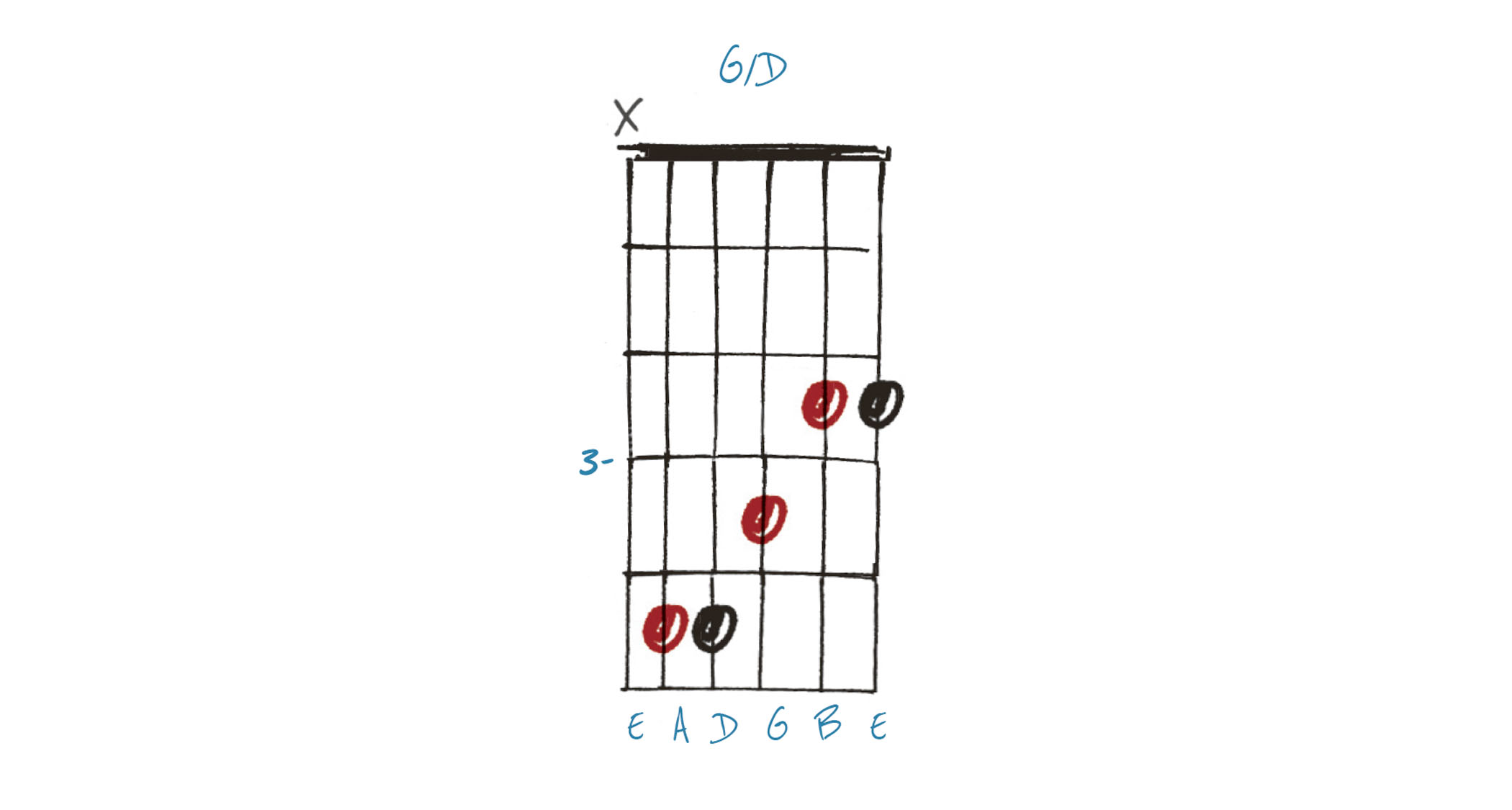

Example 3. G/D

Here’s another shape that gives us a second inversion, in this case a G/D. We’ve simply omitted the root, leaving the 5th (D) at the bottom.

Obviously, if the bassist plays a G root under this it won’t be particularly effective, but on the flip side you could ask them to play a D under your regular G chord or powerchord.

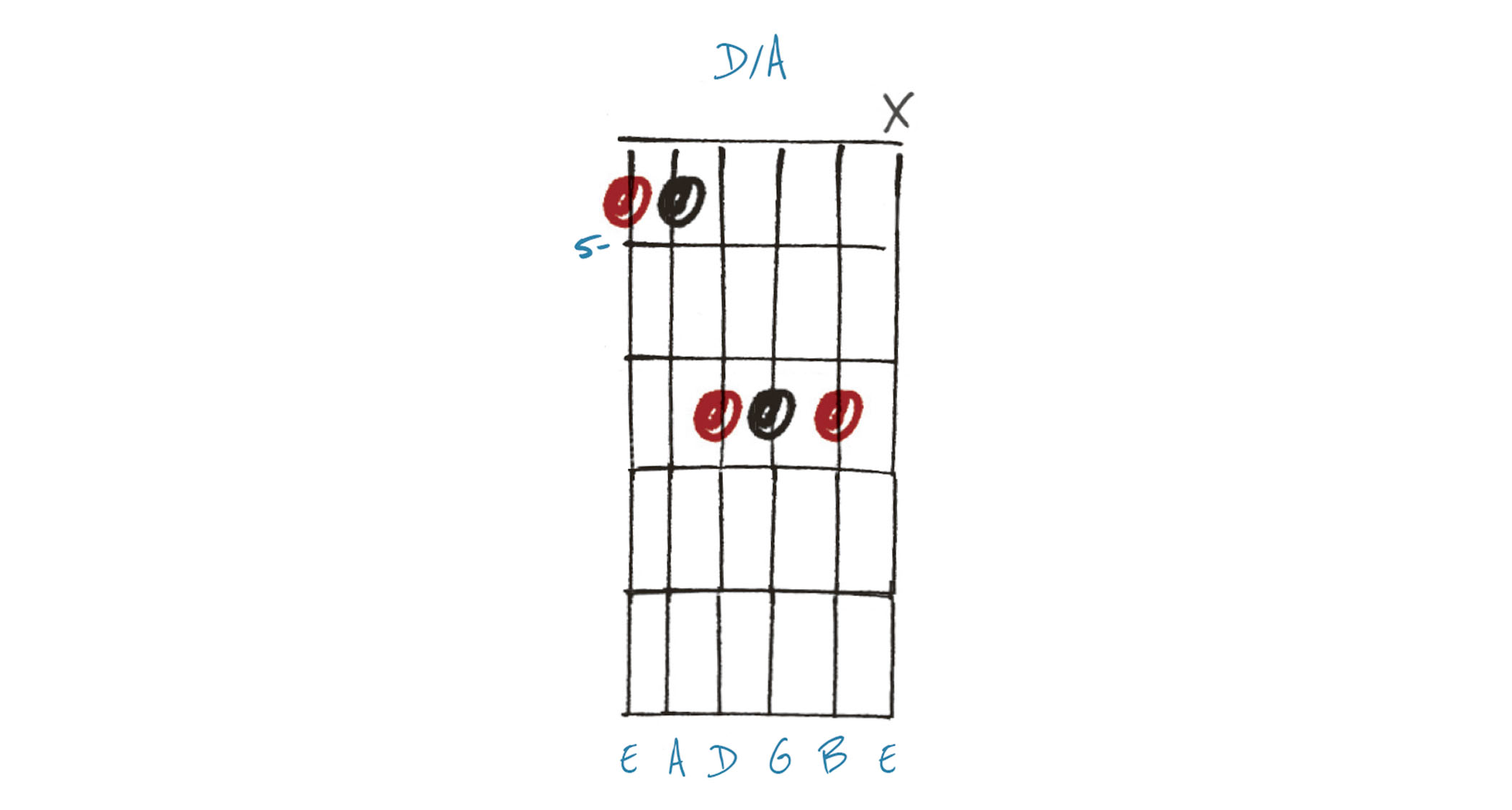

Example 4. D/A

Here’s another shape that you’ll find useful for exploring the second inversion sound – in this example, a D/A. It’s a darker, more grandiose sound than a regular D major.

This could be the perfect way to give a more standard chord progression a lift, without getting too complex or losing its character.

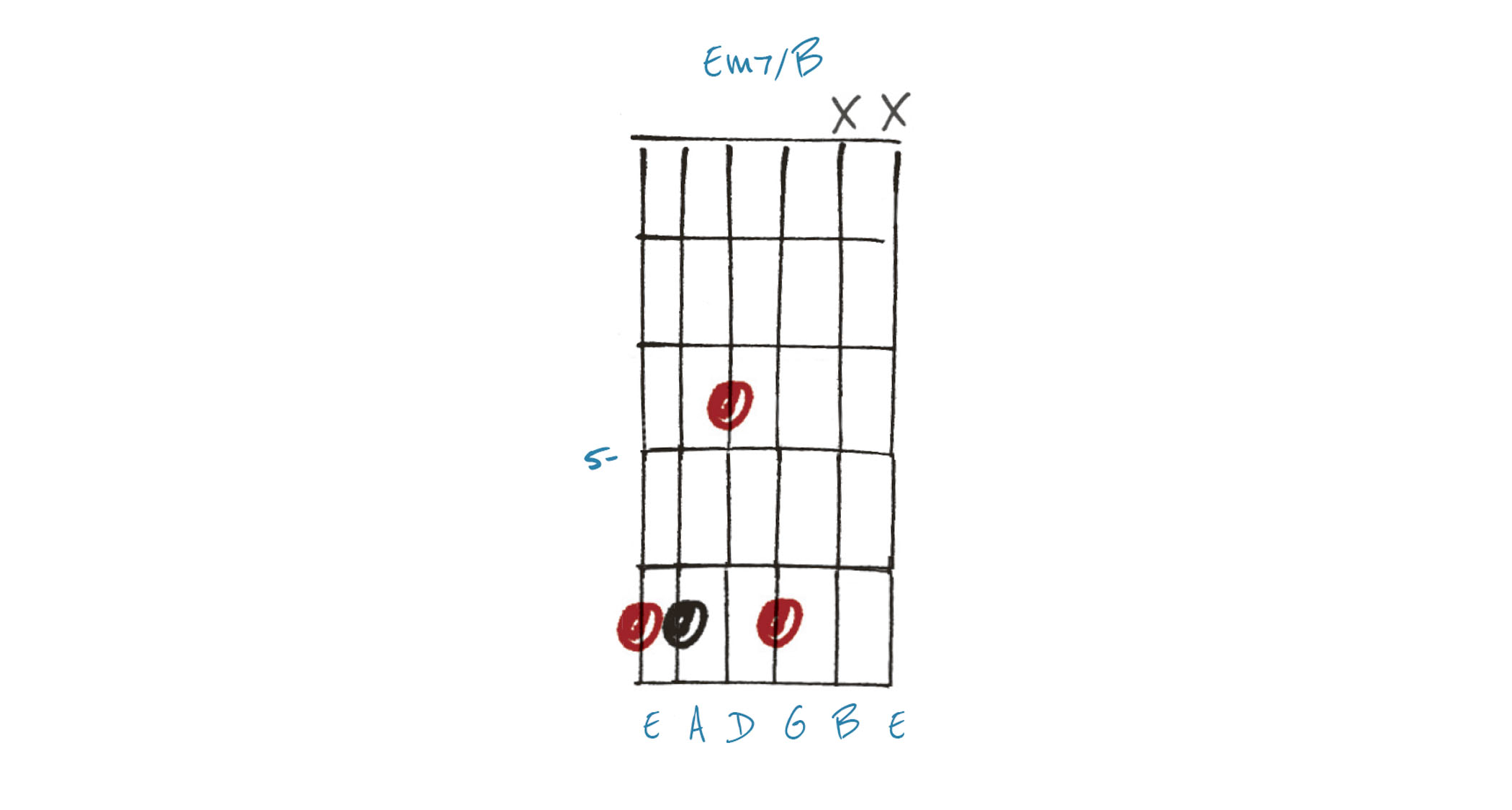

Example 5. Em7/B

This movable shape allows us to play a second inversion minor 7 chord anywhere on the fretboard. It’s an Em7/B.

In this position, you could allow the open first and second strings to ring. Give it a try – while this won’t work everywhere, there are some nice surprises lurking.

- This article first appeared in Guitarist. Subscribe and save.

As well as a longtime contributor to Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, Richard is Tony Hadley’s longstanding guitarist, and has worked with everyone from Roger Daltrey to Ronan Keating.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.