This iconic jazz progression was played by countless guitar legends – and it can help you learn the chord secrets of Joe Pass, Barney Kessel and Wes Montgomery

Want to add sophistication to your chords? Master this essential chord progression as played by 5 guitar legends

For many guitarists, one of the major draws to learning jazz and jazz blues is the richness and beauty of the chord work: a tapestry of stunning voicings and extensions that brings a whole new level of emotion and depth to the music.

Jumping into this world can seem daunting at first, so let's simplify the process so you can play gorgeous new chords in a way that is inspiring and easy to understand.

One of the most common progressions in jazz, and in popular music generally, is the I-VI-II-V progression. In the key of C major, this would involve the chords C-Am-Dm-G or Cmaj7-Am7-Dm7-G7 if you wanted a jazzier sound.

Often used as a turnaround, this sequence forms a solid foundation which we can modify with extensions, voicings, inversions and substitutions – the options are almost endless!

Sometimes you’ll end up with a progression that on the surface may appear to bear little resemblance to its humble I-VI-II-V beginnings, but dig a little deeper and you’ll see that there is a logic to explain how and why we end up there.

For this article, you will get to understand a handful of these common modifications. These will provide more artistic freedom of chord choices, so you can express yourself with sophistication and richness. So let's take a close look at some of the tricks of the trade, as used by a handful of jazz guitar legends.

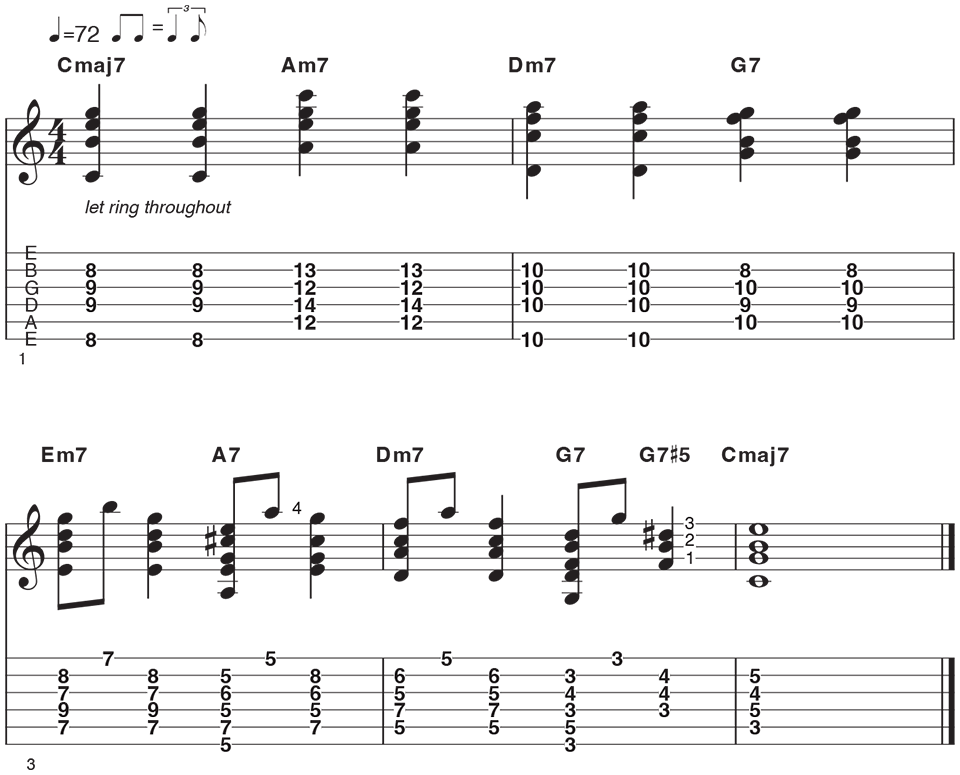

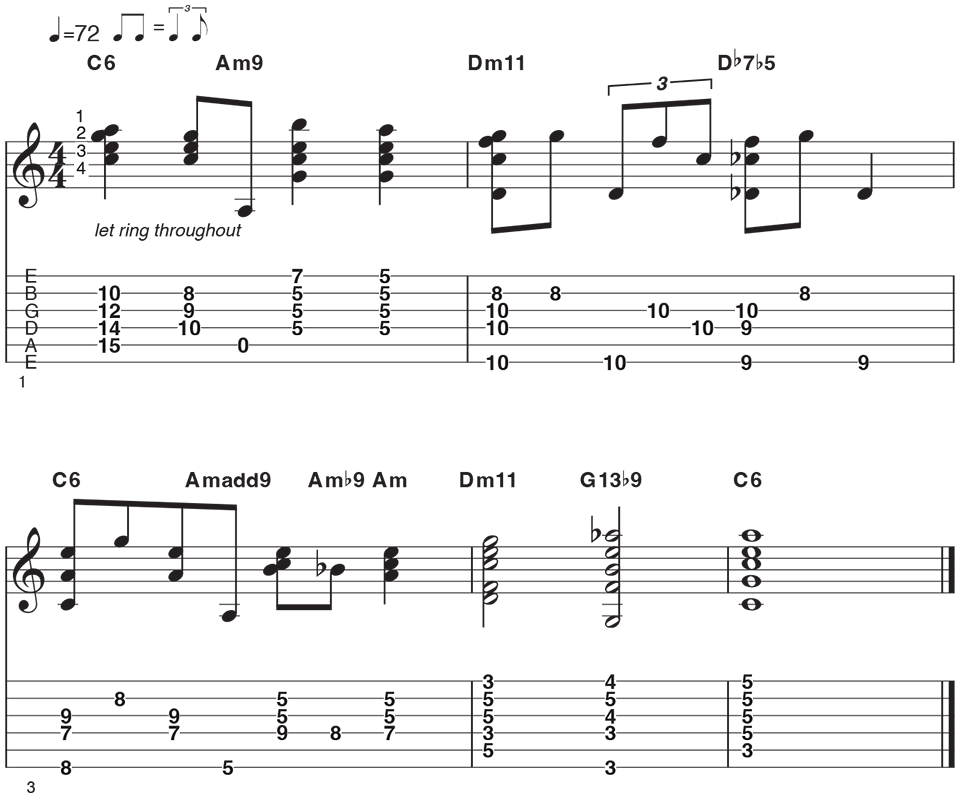

Example 1: The foundation

First, let's establish a basic starting point; a purely diatonic I-VI-II-V progression in the key of C major. Diatonic simply means that we’re using only notes from our parent scale to build these chords, the C major scale in this case. This progression will be the template for this article, allowing you to adapt and modify these changes in interesting and inspiring ways.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Notice that each and every chord is extended with its 7th: The I chord is major 7th (Cmaj7), the VI and II chords are both minor 7th (Am7 and Dm7), and the V chord is a dominant 7th (G7).

For the second pass through the progression, you will go straight in with a couple of common modifications: a substitute for the I chord (Cmaj7) with the III chord (Em7) to add a minor vibe. Then the quality of the VI chord will change from minor (Am7) to dominant (A7) in order to set the II chord (Dm7) more elegantly.

As far as voicings go (ie how the chord's notes are placed together), the most useful and common options are used for each chord type throughout this example.

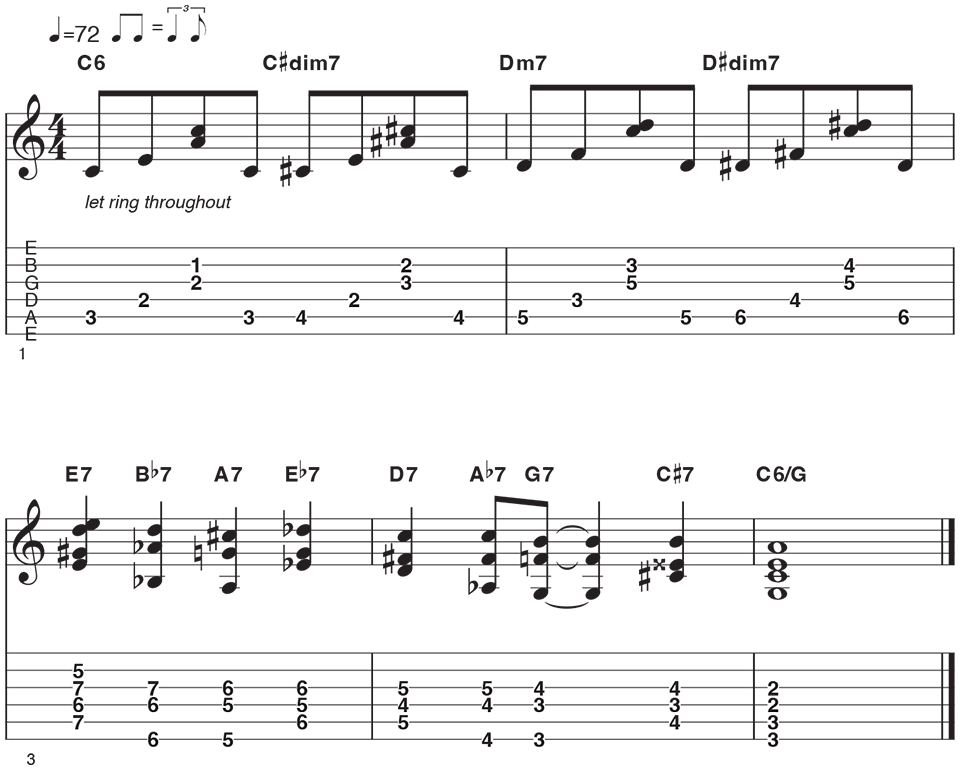

Example 2: Herb Ellis style

Here you'll take a look at how Herb Ellis might have extended these chords further, and be introduced to some important modifications. Instead of a Cmaj7 chord, this time you'll play one of my personal favorites, a C6 chord. This is a straight major chord with a 6th added: C major with an A note. This is a bedrock chord of swing and traditional jazz, not a plain major and not as bluesy or (perhaps) unresolved sounding as C7.

A couple of diminished 7th chords (ie four notes, each a minor 3rd apart) are introduced to create a chromatic climb in the bass, before cycling back around and using dominant chords for the III, VI, II and V. Notice the use of passing chords a semitone above the destination chord each time also (eg Bb7 passes to the destination A7). This adds a slinky bluesy flavor to the progression.

Lastly, enjoy the final C6/G chord: C6 in second inversion (5th in the bass). It's one of the richest and sweetest low voiced chords you can play on guitar. More importantly, it's very jazzy sounding!

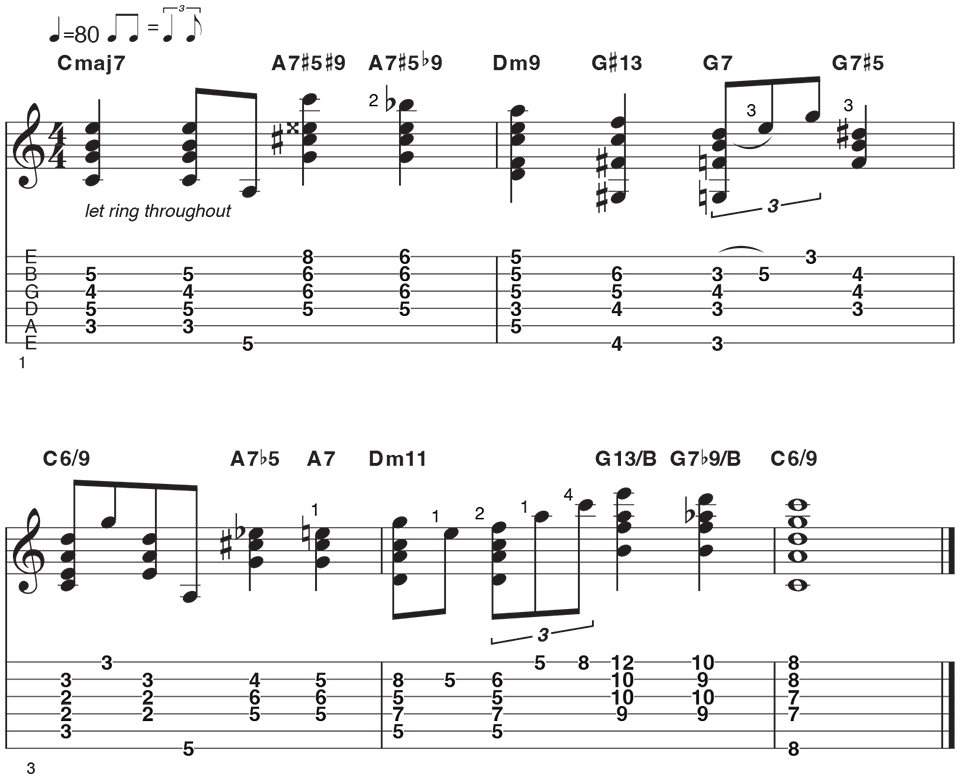

Example 3: Joe Pass style

Joe Pass was a true master of adding movement and internal melodies within his chord changes - his 1975 live duet show with Ella Fitzgerald in Hannover is a must-see for just how incredibly adept he was at this as a sole accompanist.

You'll expand your chordal palette even further with the addition of minor 11ths, Dominant 13ths and stacked alterations: rich and sophisticated extensions to 7th chords. There are also internal melodic movements into the chords.

Adding movement to chord changes is about maintaining momentum, sometimes along the bass strings, other times on top of the chords, or even in the middle of them. All three approaches feature throughout this example.

Notice the G#13 chord preceding the G13, similar to the Herb Ellis example: this is simply a passing chord (G#13: a richer version of G#7) a semitone above the destination chord (G13).

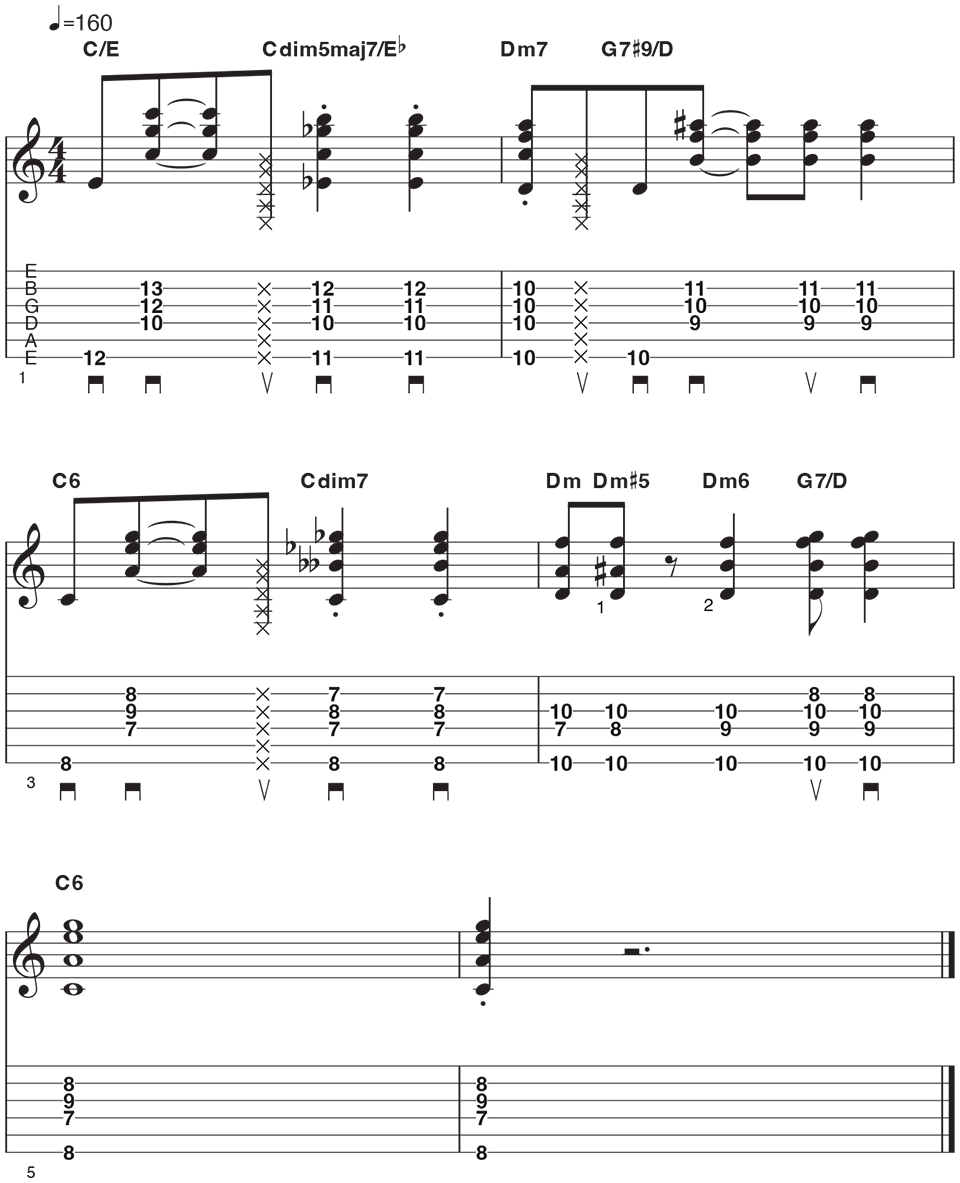

Example 4: Johnny Smith style

Johnny Smith was quite the chord magician. His use of dense closed voicings, often moving alarmingly quickly, created an almost otherworldly, organ-like tone. In this example the tempo is kept low which allows your focus to be about clean and articulate technique.

These stretchy chord voicings are a great work-out for agility building and hand posture. Make sure to keep your thumb low down at the back of the neck in order to allow your hand to fully open up. It’s also important to keep a shallow wrist angle as anything too severe will cut your mobility down right away.

The opening C6 chord voicing is a good example of a closed voicing, which simply means that the intervals in the chord remain in perfect ascending order. In this case, you have the C major triad running from low to high on the fifth to third strings, with the 6th (an A note) added on the 10th fret, second string.

There’s a certain magic to this sound and it’s a world worth exploring. Notice the use of more upper extensions on the minor chords: 9ths and 11ths.

Take note of the Db7(b5) voicing in Bar 2. This is a tritone substitution and is as simple as taking the original G7 voicing from the opening progression, and swapping the G bass note, for the note three tones (a tritone) away which is Db. This helps the bass to resolve seamlessly down a semitone further to the C note in bar 3.

You'll use two different voicings for the Dm11 chord, one contains the 9 also and one omits it. Then for the cherry on top, you'll play a Johnny Smith classic dominant chord voicing; a G13(b9). It's a good finger-tangler of a shape that requires a thumb over the fretboard for the G bass. You can always choose to omit the bass note if you prefer though. This chord resolves beautifully to C6 - notice the chromatic voice-leading along the first string in the last three changes (G, Ab, A).

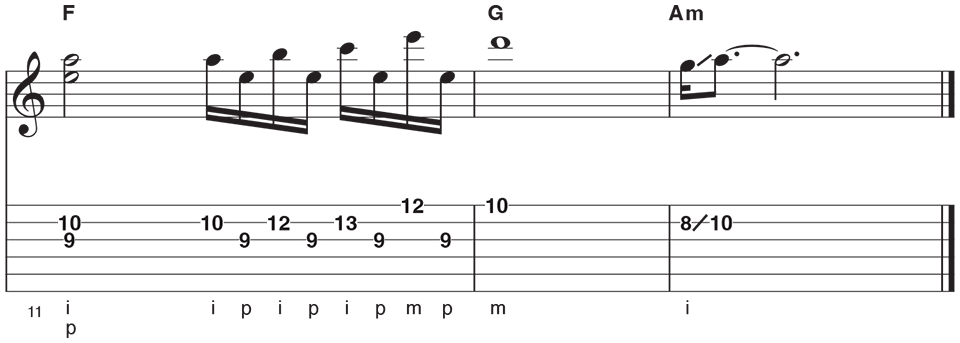

Example 5: Barney Kessel style

Barney Kessel’s playing was often lively with a keen focus on swing, groove and pocket. Here you'll look at how the I-VI-II-V progression can make for the perfect, hard-swinging mid-tempo intro.

You start off with a C major in first inversion (ie the chord's third - E - is the lowest note) played as a spread triad. Then there's a common substitution; swapping the VI chord (here, it would be Am7) for a diminished 7th built off the root of the key.

In Bar 1 the diminished 7th is highly colorful as it’s not Cdim7 in root position (ie the C is the bass note) but Cdim7 in first inversion (Eb is the bass note) with a spicy major 7 (B note) at the top. In isolation, this chord can sound odd and tense. However, within the context of Bar 1 moving to Bar 2, it’s simply a jazzy passing chord that is evocative of guitarists like Barney as well as pianists like Oscar Peterson and McCoy Tyner.

The chromatic bass-line continues as you connect to the II chord (Dm7). You then cycle round the same progression again starting with C6. This time you use a favorite Barney Kessel/George Van Eps/Freddie Green/Matt Munisteri style manoeuvre for the II-V. Bar 4 starts with a spread Dm triad before walking the middle note of the chord up to the major 3rd of G7 (a B note).

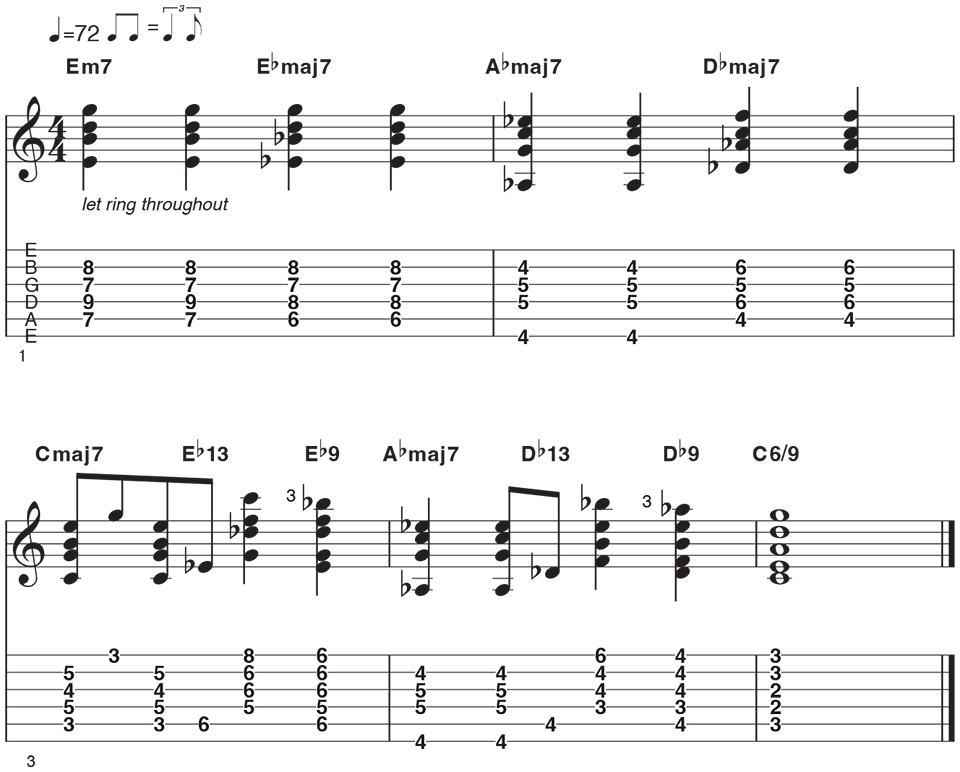

Example 6: Wes Montgomery style

Wes Montgomery was a huge fan of the “ladybird turnaround”, a progression derived from Tadd Dameron’s 1939 tune, Lady Bird. Based in C, this would involve four major 7th chords: Cmaj7-Ebmaj7-Abmaj7-Dbmaj7. This sublime little run of chords soon became another very popular turnaround amongst bebop and swing musicians. Although not technically hard to play, theory wise it benefits from a little explaining.

Starting on Em7, you're re-using the trick of subbing the III chord in place of the I (Cmaj7). From there you get into tri-tone substitution - Eb being the tritone sub of Am, Ab being the tritone sub of Dm and Db being the tritone sub of G7.

Wes liked to use a mix of major and Dominant chord types for these progressions, so do play around with as many options as you can think of here. Try using various major 7ths, or all major 9ths, or perhaps all dominant 13ths.

In short, mix and match to your heart’s desire!

Jazz legends in action!

Joe Pass - Ain't Misbehaving

Joe was as creative as he was virtuosic. Watch how he navigates the chord changes and creates intricate inner melodies with confidence and clarity.

Tal Farlow - Misty

Tal was renowned as a fast player with big hands. Watch how he uses his thumb to grab 7th, 9th and altered chords as well as the ease of his picking hand during this beautiful jazz song.

Wes Montgomery - Here's That Rainy Day

If you can take your eyes away from Wes' unique thumb-only picking style (and how he splays his fingers out on the pick guard), you will see much beauty coming from his fretting hand as he uses single notes, octaves and chords for the rich changes to this famous piece.

Alex Farran is a professional musician in the UK, who specialises in gypsy jazz, early swing, trad jazz and fingerstyle acoustic. He also teaches everything from jazz to rock and country.

- Jason SidwellTuition Editor – GuitarWorld.com, GuitarPlayer and MusicRadar.com

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.