Guitarless practice: how to learn without the instrument, and improve your musicality anytime, anywhere

You don't always need a guitar to improve your six-string skills

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Unfortunately, all us guitarists have to spend most of life away from the strings. We all know what it’s like to be stuck in transit, itching to get back home and play, or to be sitting at a desk somewhere, staring blankly at our screen as musical thoughts distract us from whatever we’re supposed to be doing. Let’s be honest: most of the time, we’d prefer to be jamming.

This lesson seeks to encourage these tendencies. Or rather, to suggest a few ways to use time away from the instrument for meaningful musical improvement. Below, we sample five areas of ‘guitarless practice’, aimed at expanding your conceptual toolkit, developing your rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic command, and broadening your overall approaches to playing.

The phrase ‘be a musician, not just a guitarist’ is one of the best clichés out there - while the guitar is a brilliant way of getting music ‘into and out of’ ourselves, the music itself must always come from us. So for me, guitarless learning is an essential component of wider musical progress - after all, the hands can only ever follow the head.

No twentysomething could ever claim to be a real authority on the inner lives of the world’s musicians. We play music in our billions, and every creative mind has infinite shades within it.

So this is more of a brainstorm, grouped into five rough areas - ‘listening modes’, ‘physical actions’, ‘smartphone apps’, ‘musical reading’, and ‘asking the community’, along with a few other oddball suggestions along the way.

Listening & absorbing

Musically, we are what we feed ourselves. One obvious way of using guitarless time is to listen to more music - either by going deeper into what we already like, or by finding new, fresh sounds. There are many ‘modes’ of listening, which I think you can roughly group into:

- Casual: listening to music while doing something else - e.g. headphones in the office

- Active: primarily focusing on the music - e.g. sat down at a classical concert

- Reflective: ‘mirroring’ the music in some way - e.g. moving, singing or tapping along

- Reinterpretive: adding your own elements - e.g. humming a new bassline

Naturally, these categories oversimplify (e.g. most people can focus better while cooking than reading), and are somewhat arbitrary (e.g. what level of head-nodding would turn active listening into reflective?). But it’s worth being conscious of your habits here, and aiming for more involved listening modes when you get the chance.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

This can be as easy as closing your eyes and zoning into your headphones rather than half-reading billboards through the train window. But you can take it much further too - hear the late, great experimental composer Pauline Oliveros’ influential take on ‘radical attentiveness’ as a broader orientation towards life as well as music:

Ease of choosing: It’s often a faff to get to the music we actually want on a phone screen, especially when on the move. I find it’s absolutely worth spending a little time each month adding new albums and artists to your iTunes, Spotify, etc - and also making them easily accessible in ‘Recently Added’ playlists or similar (if you use an iTunes library then check out ‘Smart Playlists’ - and, for me, the iTunes Match cloud database is definitely worth the £22/year, making all my music available on all my devices).

I’m not going to go into a ‘how to find new music’ brainstorm here (definitely a future lesson topic), except to say that nobody ever seems to regret pouring some proper time into it.

And I’d encourage everyone to look globally as well as locally (isn’t it strange that a record store may have dozens of aisles each for rock, classic rock, blues-rock, punk, alt-punk, pop-punk, etc...and then a single shelf in the corner for ‘world music’ - i.e. the other 99% of the globe’s sonic variety, all filed under a single header?)

So it’s worth taking some deliberate time to broaden your search (e.g. try starting here - a thing I wrote for this very purpose, tracing hidden sonic links between Indian classical and rock, blues, jazz, jungle, hip-hop, house, techno, ambient, minimalism, and Western classical). And for a different spin on a similar principle, check out Adam Neely’s excellent video on ‘Learning to Like Contemporary Christian Music (the music I hate)’.

Physical immersions

If you’re somewhere where you can make noise, you can turn to more involved modes of ‘reflective’ and ‘reinterpretive’ listening (i.e. mirroring the music as it plays, or adding something to it). There are many ways to physically relate to music without an instrument in your hands - the three most fundamental are probably:

Dancing: Any method of ‘moving to music’ will deepen your connection to it: foot-shaking, headbanging, dancing, a full-sensory mosh-pit, etc. ‘Shape-based’ memorization techniques are known to have incredible strength - and dance, as a powerful form of ‘embodied cognition’, adds further layers of long-term mnemonic reinforcement, while imbuing the patterns with broader connective and emotional resonance.

Singing: don’t be shy if nobody’s around... and in any case, you can choose the music that suits your voice (and can improve fast as well - this is a good blog on basic vocal technique, posture, breath control, etc).

Try harmonizing, copying non-vocal melodies, or anything else that comes to mind. You can start by just holding a long note over a static Indian tanpura drone, and then exploring outwards from there at your own pace.

Tapping: ever since our proto-human ancestors began banging sticks and rocks together in sequence, percussion has been a cornerstone of our shared music. So try just tapping your fingers on your desk, or in your pockets as you walk along, etc. Keep things simple, solidifying the basic groove before adding the intricate details.

Start by thinking in terms of ‘kick & snare’ (even if there’s no actual kit in the music), and find some corresponding ‘low & punchy-mid’ sounds from the surfaces around you. And see how far ‘body drumming’ has been taken by the tabla gurus of North India:

Innate fundamentals: These three basic actions - dancing, singing, and tapping - appear to be human universals, arising more from biology than learned culture. Infants all around the world will spontaneously vocalize, jiggle around, or clap their hands in response to hearing music.

In fact, cultural influences often act to constrain these primal impulses - e.g. dull, notation-based school classes, teachers who discourage or ignore improvisation, and the general embarrassment of singing in front of people, etc. (Why else do most people tend to let these things out so much more while alone?)

Anything that draws directly from such fundamental musical-cognitive processes is well worth spending some time on. You don’t have to sing, dance, or tap very well - but building up some non-guitaristic ways of ‘representing the shapes of the music’ will help form new pathways and neural connections, aiding you in your broader musical explorations.

The better your inner ear is at capturing the patterns as they zoom past, the more the fog will clear across the whole landscape of learning.

Try something as simple as moving one of your hands upwards and downwards in rough proportion to the rise and fall of the melody - this will instantly speed up your ability to internalize new musical patterns.

You can also try and visualize (or subtly pulse your fingers to) the notes as played on an imagined guitar, building up a vivid ‘inner fretboard’ over time. The principle of finding many different ways to recreate the music’s ‘shape’ will rarely let you down.

You’ll be taken aback how much your physical technique will improve when you’ve built up a little more mental headroom. ‘Technique’ is a pretty vague concept, and even ‘muscle memory’ is predominantly about changes in the brain rather than the hands. How often is it that your finger actually can’t reach the desired fret, rather than your brain not sending it the right set of ‘instructions’ in time? If you free your mind, your hands will follow.

Ideas from around the world: Different musical cultures have developed various methods of embodied musical learning. To name just a few: Indian classical instrumentalists break down melodies with ‘sargam’ (basically ‘sa, re, ga...’ instead of the ‘do, re, mi’ of Western solfège), and South Indian drummers utilize the ‘konnakol’ system of rhythmic vocalizations (fun and incredibly effective).

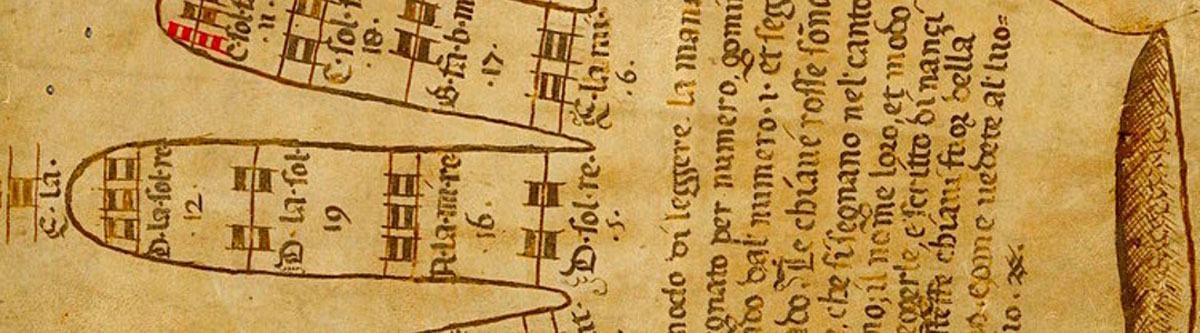

The ‘Guidonian Hand’ (pictured) - basically, imagining musical ‘maps’ on your palm - was used to help students learn to sight-sing in 10th-century Italy...and there are of course countless more!

Smartphone apps

While the sheer variety of music-focused apps offer is impressive, many are of limited use. They’re often clunky, or aim to solve problems that don’t really exist, with dubious, ad-riddled explanations of simple concepts.

So first, be conscious of what areas you really want to improve on, and consider what you might actually enjoy using. Always worth reading some independent reviews too.

But if you gather the right ones, apps can be fantastic, giving quick, easy access to modes of learning that were unthinkable to our teachers and heroes. There are countless gadgets covering ear training, sight reading, internalizing new rhythms, exploring microtonal sounds, etc.

And while it can be a challenge to turn the smartphone into a zone of focus, it can be done. Here’s a haphazard selection of interesting and/or useful music apps I’ve been using recently (for iOS, but most have Android versions too):

- Time Guru: easy-to-use metronome without unnecessary frills

- Quiztones: ear training skills for audio engineers - EQ, noise, etc

- Functional Ear Trainer: the best app for intervallic ear training

- PolyRhythm: two-layered metronome - endless rhythmic fun

- Clapping Music: learn Steve Reich’s intriguing 1972 composition

- Oblique Strategies: Brian Eno’s ‘card deck for lateral thinking’

- ReadRhythm: fantastic primer for sight reading rhythm notation

- Wilsonic: curious app full of microtonal, geometric scales

- TAQS.IM Synth: microtonal synthesiser, with many global modes

- iReal Pro: thousands of downloadable MIDI chord progressions

Also, make good use of the standard apps - Notes, Voice Memos, Spotify, etc. You can record or film your own playing and review it later on, picking apart areas of improvement and seeing new ideas and possibilities in what you’ve already done. Then you can pick up the guitar with fresh ideas at your fingertips. Try keeping a physical notebook around too.

Music-focused reading

Musicians tend to lead footloose, mobile lives. Sometimes I end up spending more of the week on public transport than on playing or performing (...and things were a lot worse when I had an office job). This is a massive amount of time, and it has to go somewhere - and a few bursts of musical focus will make the journey pass more quickly, and leave you with a momentum boost to get off with too.

Many of the apps above are great in transit - and of course you can just sit back and listen as well. But public transport can be distractingly loud, and an awkward place for dangling headphone wires.

Reading is often a better alternative for these stop-start environments - especially old school, physical books, which will always remain blissfully free of cookie popups, slow connections, page-switching delays, irritating shoe ads, etc. E-readers tick most of these boxes, and laptops, and phones can of course work well too.

Are there good biographies/interviews of your musical heroes? Or articles/novels that will add emotive color and context on their creative process? Or even scores/analyses/discussions of your favorite tracks?

Again, I’m not really going to suggest what to read - just think about what you’d like to learn more about (well, actually I am going to shamelessly plug my own website: www.ragajunglism.org if you’re interested in guitar, jazz, rhythms, Indian classical, global improvised music, etc. Always ad-free and open access.)

Community conversations

Nobody is really ‘self-taught’. Even guitarists who don’t take formal lessons will absorb ideas and techniques from those around them, and today virtually everyone has learned from tabs and followed along with YouTube tutorials.

The main advantage of in-person tuition is its real-time, responsive nature. I was watching Pat Martino’s instructional DVD the other week, and the ability to pause and clarify a few things would have doubtless eased my numerous confusions (‘umm, could we go over ‘chromatic hypercubes’ again?’).

However, the internet enables us to do this in some form at least, allowing for various modes of two-way interaction. We can learn from - and listen to - each other more easily than ever before. So if you’ve thought something through carefully and are still left with questions, then...

Get good at Google: Most guitar queries have already been answered somewhere, although you might have to dig around a bit. Getting familiar with Google’s custom search operators is a huge timesaver - for example [site:www.guitarworld.com] will restrict results to that domain, and [“Jimi Hendrix”] will return only that exact text string.

There are lots more - e.g. you can find papers and book scans with [-filetype:pdf], recover archived versions of pages that are offline with [cache:www.site.com/page], or exclude particular terms with the minus operator ([-Bono] will exclude all pages that mention his name).

Chat to the guitar community: The modern internet originally grew out of lo-fi message boards and forum sites. Today’s online landscape offers a vast selection of places to ask others for advice - Ultimate Guitar and TDPRI are well-established, and Reddit has subs of varying quality (r/jazzguitar, r/guitarlessons, and r/musictheory are good).

Find the most specific place for your query (e.g. the ‘Wes Montgomery’ section of jazzguitar.be), and keyword search for any similar topics (e.g. ‘SRV string gauge’). And there’s nothing wrong with being a noob, but read through the forum’s rules first. Or see it the other way, and search out questions you might be able answer.

Ask the artists: You’ll be surprised how many famous artists will take real time to reply to fan questions in depth. Many invite it via social media and AMAs (‘ask me anything’ sessions) - e.g. Reddit has had good sessions with Tommy Emmanuel, Andy McKee, and Bjork (“eternal spacious space of space...creativity always lives somewhere in everyone, but its nature is quite pranksterish...”).

I’ve also had fruitful conversations with some of my musical heroes through just emailing them with a few thoughtful questions. Top tips: keep it concise, talk to them like humans rather than demi-gods, and demonstrate that you’ve already been through the info already out there (‘so, Ravi Shankar, how many strings does that thing have again?’).

Roundup

Use these powers wisely. Not because they’re likely to bring any direct harm to you or those around you (...although I’ve occasionally got odd looks from passers by on Blackheath). But because it’s good to know how and when to be fully attentive and present in the non-musical world too.

I’m not going to get all German children’s tale about it (although n.b. the tale of ‘Hans Head-in-Air’, written in 1845, serves as my legal disclaimer against any and all liabilities arising from absent-minded readers walking into lamp-posts, forgetting to turn the taps off, or, like Hans, falling in a canal...you have been warned).

But it’s good to stay present, which means knowing when to zone into music, and when not to (and also, how to disguise it). Us musicians don’t tend to have the best rep for this...

In many ways, having a passion and drive for musical learning isn’t necessarily so different from having a low tolerance for boredom. But whatever your motivation, we all end up having many moments of ‘guitarless practice’ in some form or another.

So it’s worth gaining a little more control over the direction and focus, and thinking about what we want from it all. Besides, the feelings of flow and purpose are empowering, and will help keep your soul intact amidst the psychological clutter of the modern world.

I interviewed master mridangam drummer Trichy Sankaran about this: “I’m one of those people who constantly thinks of laya [rhythm]. I can’t help but see it in the world around me - if I’m at the airport then my mind will wander, and...trains have their own particular rhythms... even the street noise can take on rhythmic qualities.”

I used to play silent ‘rhythm games’ to help keep my mind alive through the grey mundanities of being a corporate consultant (as published in David Graeber’s Bullshit Jobs).

Necessity very often is the true mother of invention - and so the constraints of finding yourself guitarless can catalyze fresh modes of learning and creativity. As explained, I feel that picking up some deliberate skills here is essential to wider musicianship. But mainly, it’s just fun to have some enticing things to turn to when bored.

The clerks of the University of Ghana post office definitely agree, whistling a traditional Kpanlogo hymn over a groove made of nothing but finger-clicks, scissor-cuts and hand-stamps. My own office rhythm games definitely hindered my spreadsheet-based concentration, but these guys are using theirs to actually do their job (and, based on the bpm, I’d say pretty efficiently too). Try it out in your office and let GW know the results:

George Howlett is a London-based musician and writer, specialising in jazz, rhythm, Indian classical, and global improvised music. For more head to www.ragajunglism.org

George Howlett is a London-based musician and writer, specializing in jazz, rhythm, Indian classical, and global improvised music.