How to devise creative blues turnarounds

Joe Bonamassa offers some strategies for gaming out your blues jams and holding the audience's attention

If you've ever had to kick off a slow blues tune – and odds are that you have on at least a few occasions (more than a few for me!) – there are a number of different ways you can do it.

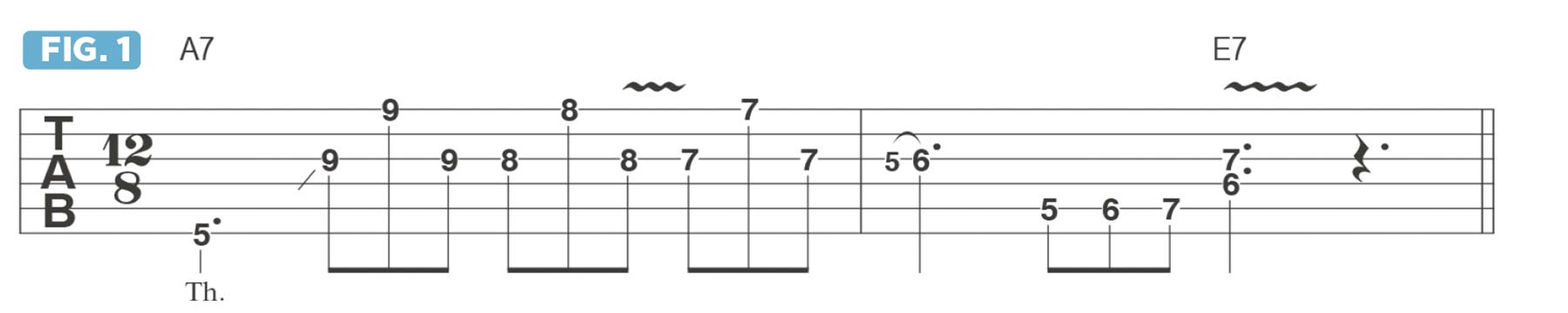

A classic way to start a slow blues in A is with the turnaround shown in Figure 1. Following the low A root note, I play chromatically descending 6th intervals, or 6ths, fretted on the G and high E strings. Most blues guitarists rely on these types of chromatically descending 6ths, or ascending ones, for turnarounds, as well as for use in rhythm parts or during a solo.

I came up with an unusual approach to the turnaround that sometimes freaks people out a little bit. The technique I’m about to demonstrate is based on sliding half-step bends, so they can sound a little jarring, in that they are not perfectly in tune.

If you have perfect pitch, watch out! There’s a bit of a rub in the way these half step bends sit on top of the chords. In fact, that is what I like about them. To my ears, this turnaround technique sounds very expressive and provides some of the “grease” that I love to hear in blues guitar playing.

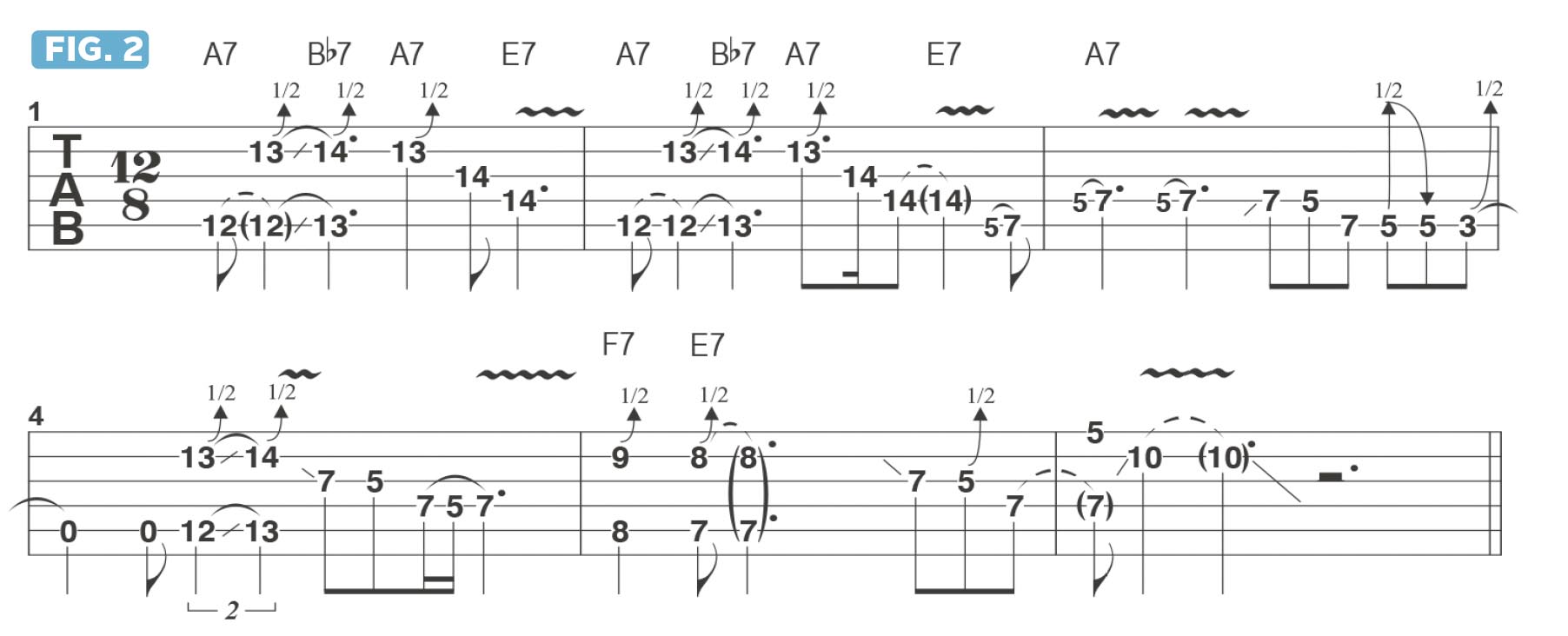

Staying in the key of A, Figure 2 starts on the tonic, with an A root note played on the A string’s 12th fret, sounded in conjunction with a half-step bend on the B string, from C, the minor 3rd, to C#, the major 3rd.

This “shape” then shifts up a half step, to Bb, followed by a descending lick that makes brief reference to the V (five) chord, E7. Bar 3 illustrates a standard single-note blues lick, followed in bar 4 by a restatement of the A7-to-Bb7 half-step bends. In bar 5, I apply this approach to F7 and E7, the latter chord functioning as the V (five), which then resolves back to the I (one), A.

The blues has been around for a while, so I think it’s always cool to find some new avenues to navigate within the boundaries of the genre in ways that sound a bit different, and these half step bends do exactly that.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

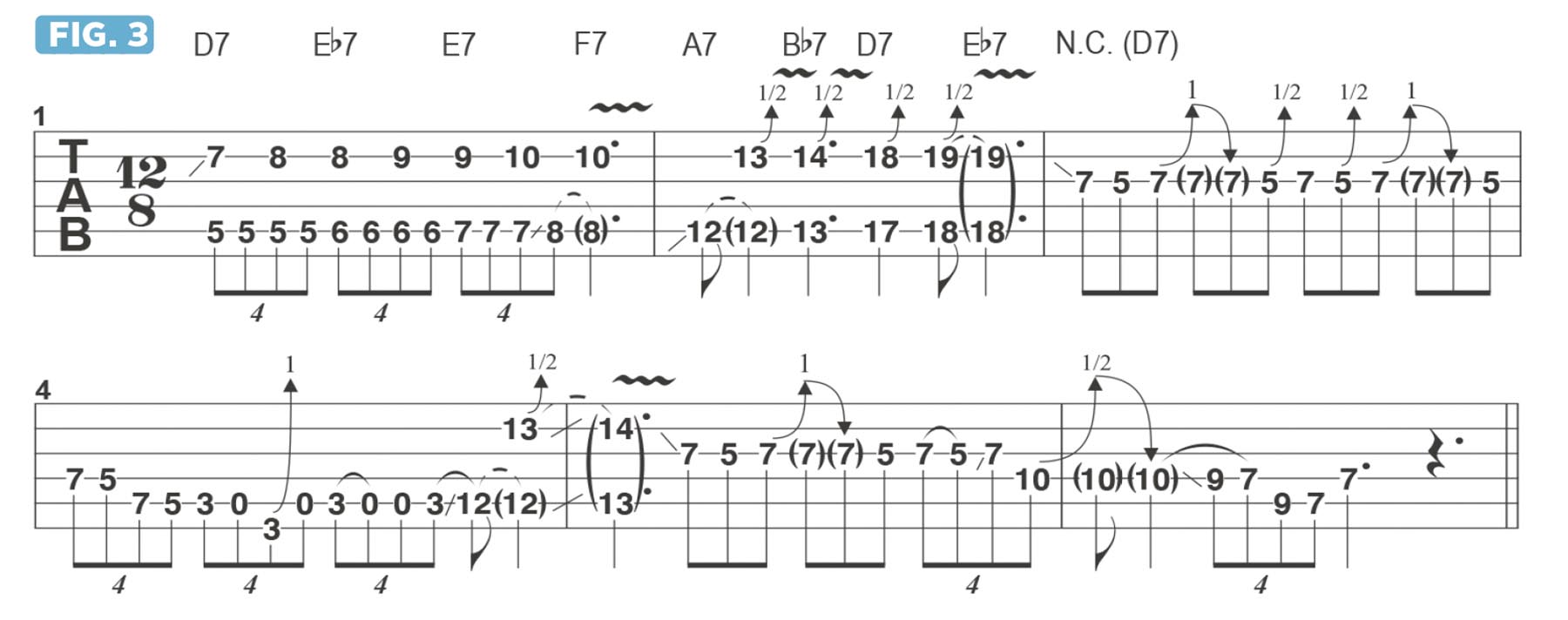

Figure 3 offers another twist. In this example, I begin on the IV (four) chord, D7, sounding the D root note along with F#, the major 3rd, which then moves up a half step to the 4th of D, G.

The idea then shifts up chromatically: keeping the G note on top, the lower note moves up to Eb, which creates the sound of an Eb tonic and G, the major 3rd, above it, after which G slides up a half step to Ab, the fourth of Eb, and then the whole thing moves up one more half step to reference E7.

Through the remainder of this lick, I incorporate the prior half-step bend technique. The sound is ominous, and I like the musical tension it creates.

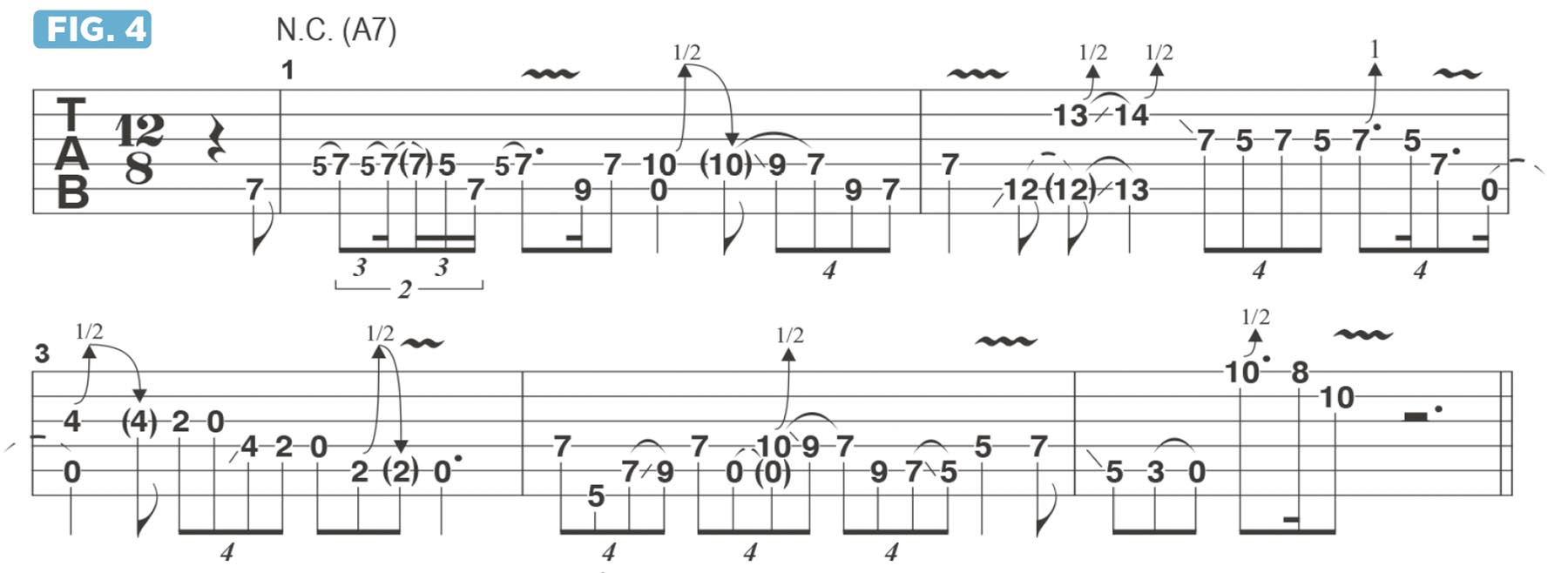

I love the Buddy Guy approach, wherein he purposely will bend notes a little out of tune to get that “rub.” Figure 4 offers another example of how to use half-step bends to give your riffs some attitude.

Joe Bonamassa is one of the world’s most popular and successful blues-rock guitarists – not to mention a top producer and de facto ambassador of the blues (and of the guitar in general).