“Improvise a musical story that makes sense, and takes the listener on a captivating musical journey”: “Call and response” phrasing can help transform a simple guitar solo into an evocative narrative device

In blues maestro Josh Smith's latest GW column, the guitarist draws inspiration from George Benson for a lesson in call and response phrasing

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Over the last few months, I’ve talked about a few of the tools I like to use to strengthen the narrative content of my improvised solos. The first is repetition, and the second is musically “painting oneself into a corner,” or what I refer to as “handcuffs.” The third approach, which we will begin exploring today, is call and response.

The basis of this approach is to listen intently to what is played as it’s happening, and then to respond to it on the fly with a phrase that “answers” the preceding one. It’s all too easy to forget to pay attention to what we're playing, and fall into “auto pilot” mode, where the fingers are just moving through handfuls of familiar phrases, based on muscle memory, allowing the fret hand to go wherever it may go.

If you intently listen to each phrase you play, the next one will be informed by it. This type of focus will enable you to improvise a musical story that makes sense and takes the listener on a captivating musical journey.

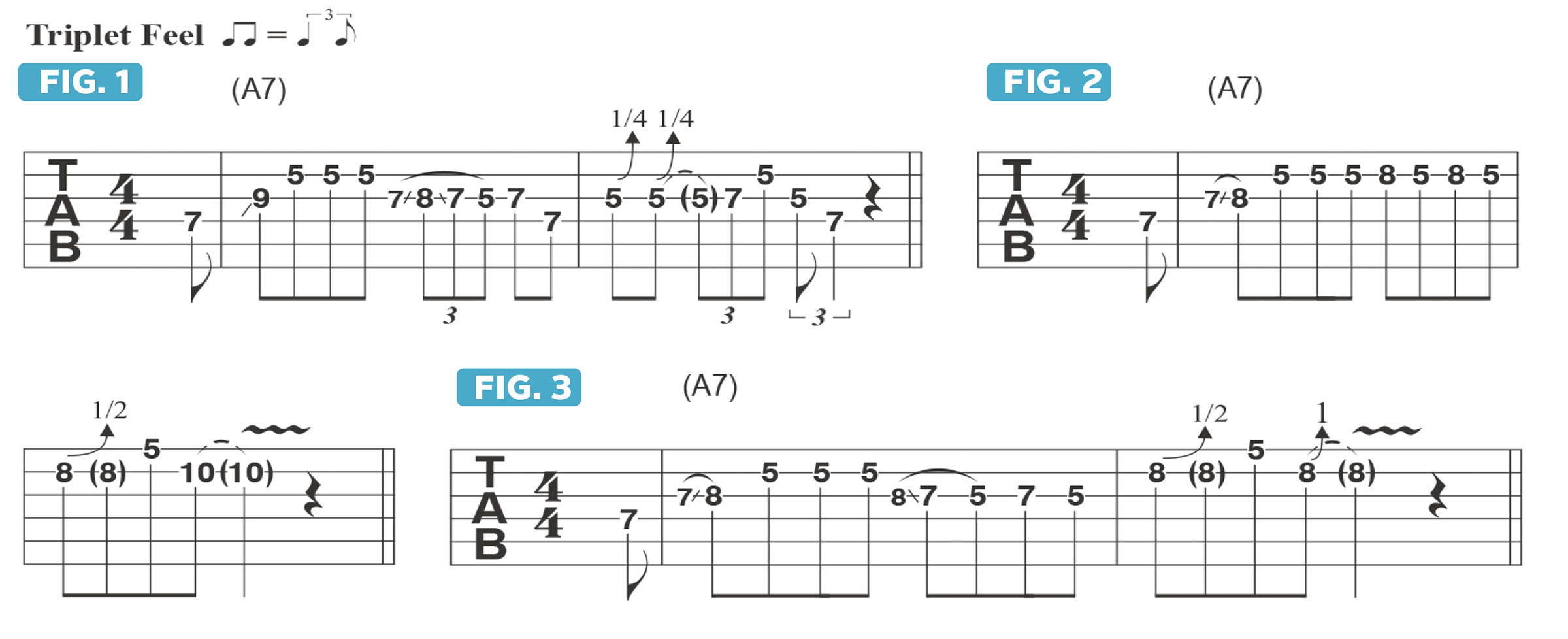

I’ll start by coming up with an unplanned phrase off the top of my head. Played with a shuffle feel in the key of A, Figure 1 is based on the A blues scale (A, C, D, Eb, E, G).

Now that I’ve played that phrase, I’ve paid attention to its phrasing and rhythm. Immediately, my brain is screaming at me to answer it with the phrase shown in Figure 2, which builds on the previous one by starting the same way, and then develops the musical idea by resolving it differently, to a high A note.

Figure 3 offers yet another twist on how I might answer my initial lick, this time wrapping it up with a G-to-A bend with some vibrato.

A great thing to think about is what George Benson does when he “scat” sings and plays, which means he’s singing all of the licks he’s playing on guitar. To my mind, George is “playing what he’s singing,” as opposed to “singing what he’s playing,” meaning he’s allowing his musical choices as a singer to direct what he plays in his improvised guitar solo.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Put yourself in the same mindset – “singing” an answer to each lick as you move through a solo. For me, this is one of the most useful tools of all when it comes to creating solos with a solid narrative content. For years, I’d sit on the edge of the bed, play a lick, sing an answer to it, and then translate that lick to the guitar. It was almost as if I were two different musicians conversing.

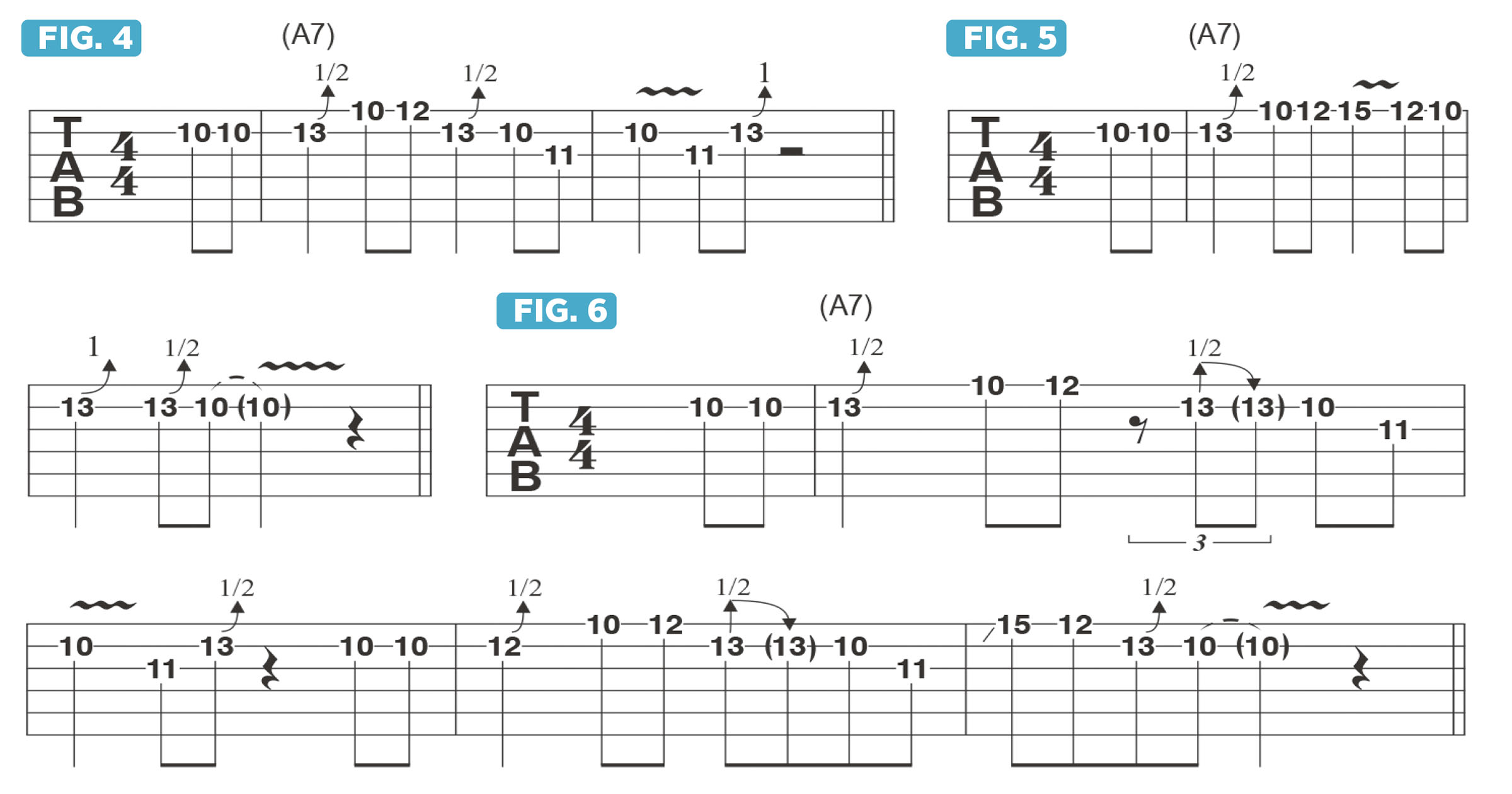

Let’s take four different phrases and come up with an “answer” for each. Figure 4 illustrates the first phrase, and once it’s had a moment to sink in, my natural answer is Figure 5, once again building on my initial idea but then wrapping it up in a different way. This same approach is demonstrated again in Figures 5 and 6.

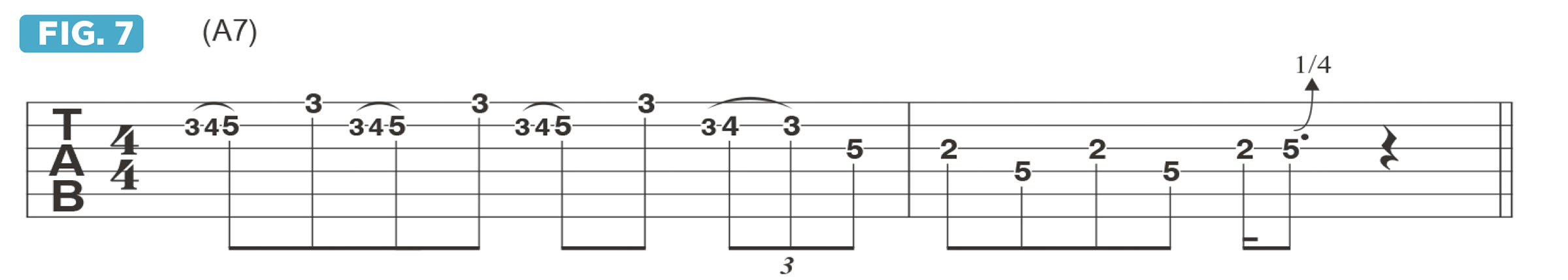

Figure 7 offers a completely random improvised idea. A great way to respond musically is to play something like Figure 8, jumping up higher on the neck to re-imagine the line in a different way.

When you approach your improvisations like this, you give them a conversational quality, which is something everyone can relate to.