Two Effective Approaches to Building Melodies

Satch dishes on how to approach crafting a melodic line for either a song’s theme or an improvised solo.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I’d like to talk about melody and how to approach crafting a melodic line for either a song’s theme or an improvised solo.

It may seem like a relatively simply task: you get some chords together, focus on the key you’re in, and play a few lines. But in reality there are so many different routes one can go when tasked with this creative endeavor.

To me, oftentimes, the “story” of the melody can be told too soon or unfold too quickly. A great way to stretch out the story is to end phrases on suspended notes, so that the listener will have to wait a little longer for the next phrase to come, in order to hear where the whole thing is going.

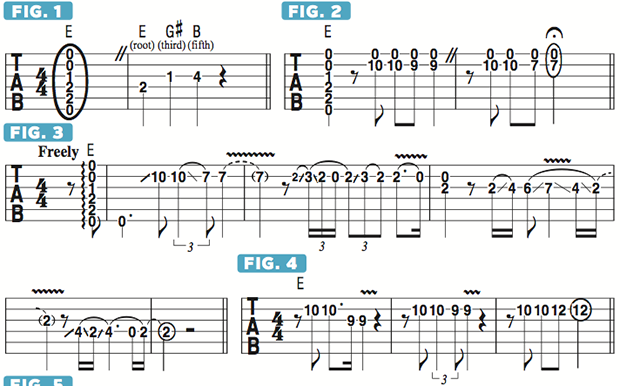

As demonstrated in FIGURE 1, if your chord progression begins, for example, with a big E major chord, playing one of the triadic chord tones—E G# or B—will not offer the listener much. But if you were to instead begin your melody with an A note, the fourth in the key of E, then you create the impression that the melody needs to go somewhere else, in effect drawing the listener in. That A note, the “sus4,” can be quickly resolved by moving to one of the aforementioned chord tones.

In bar 1 of FIGURE 2, I resolve the line by moving from A down to G#, the major third. But if we were to instead move from A to F#, the major second, as shown in bar 2, the line still retains that suspended quality and maintains the feeling that it is yet to be resolved. With an awareness of melodic-harmonic suspension and resolution, one can take as long as one wants to resolve a line.

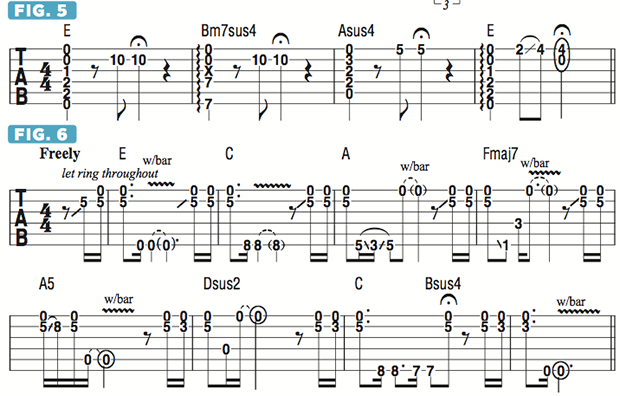

FIGURE 3 offers a four-bar improvised melody in which the first three bars are spent moving freely from one “suspended” note to another, and the line is not resolved until I finally land on E, the root note, in bar 4. The opposite approach would be to resolve the fourth to a chord tone immediately, as shown in FIGURE 4, with A moving to E, G# and B right away. Another cool, useful melodic concept is to have a melody note stay the same while the chords underneath it change. In this sense, the feeling of suspension is achieved in a different way, as the listener has to wait for the musical idea to be concluded.

In FIGURES 5 and 6, I change the chords beneath the fourth, A, and the root note E, respectively, as a way to demonstrate that, even with a one-note melody, musical interest can be instilled in the listener while the story of the melody gradually unfolds.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!