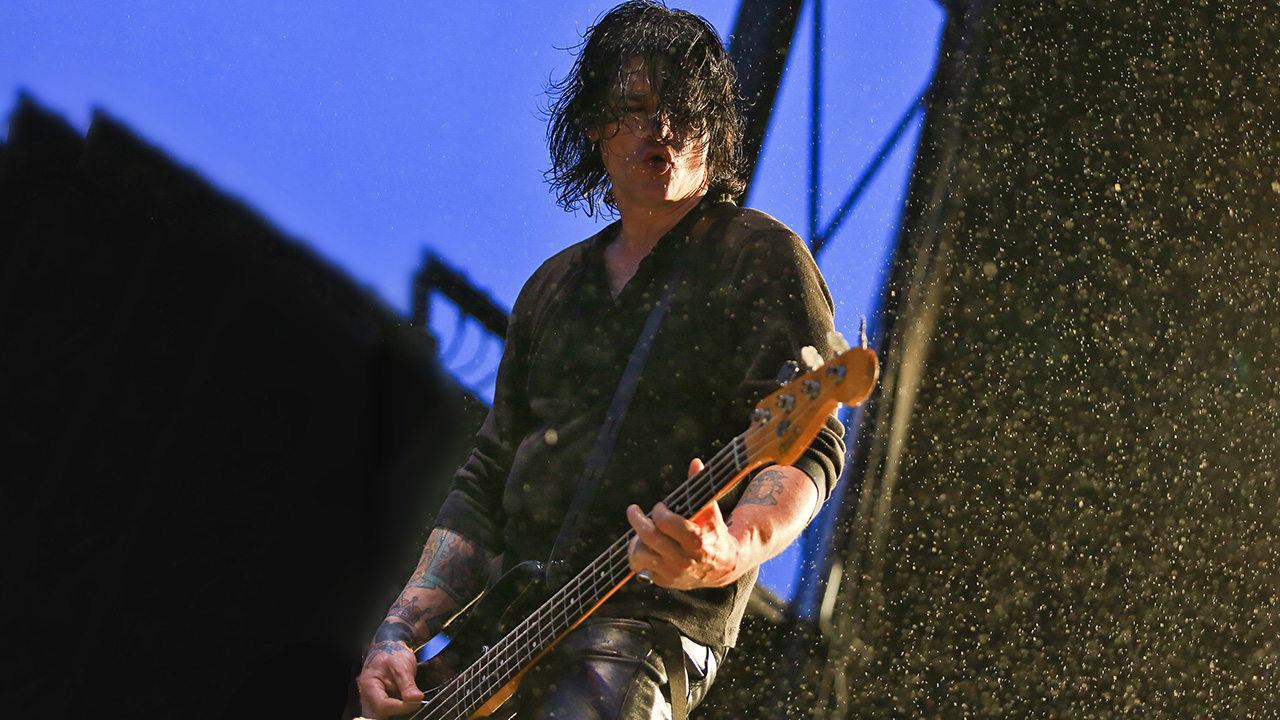

“I am brutally honest, even at the risk of losing my gig. Ace loved it because he was surrounded by people who’d say he could do no wrong. I never did that”: Anthony Esposito’s unique career alongside the Spaceman, George Lynch and Jake E. Lee

The upright bassist with no previous experience of rock joined Lynch Mob and spent years telling it like it is to his guitar player bosses. He reveals what he’d always tried to explain to Lynch, the pain of losing Frehley and his concerns for Lee

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

From the moment New York native Anthony Esposito picked up the bass, he knew he was a lifer. “I remember playing and getting calluses, and blood coming off my fingertips,” he says. “But I couldn’t get enough of it.”

That passion led to gigs with George Lynch, Ace Frehley and Jake E. Lee – but Esposito was never just a collaborator; he was a trusted friend, too. “Thank you for acknowledging that,” he says. “But I don’t know why!

“At the beginning of relationships, players like that will ask you questions. Your response will determine whether they can trust you and show if you’re the right fit for the right reasons.”

How did you end up joining Lynch Mob in 1989?

I auditioned for a band on Atlantic Records and lost the gig. But one of the publicists said, “I wanna help you out,” and she got me a bunch of auditions. One was in Arizona with Lynch Mob. I got audition cassettes of them trying out other bass players, so when I showed up they were like, “Do you want us to show you the songs?” I was like, “No, I’m good.”

The first song I played was Wicked Sensation – I knew all the changes and they were shocked! They thought I was this perfect fit, like this freak from another planet who just knew where George was gonna go next!

How did you you get on with George Lynch? He can be pretty quirky.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

He’s got a sense of humor that offends a lot of people, but I got along with him great. We spent a lot of time together when we were on tour. I got along with everyone in the band. Mick Brown was dear to my heart.

What was the key to locking in with George?

I didn’t come from a rock background; I came from jazz, punk and upright bass. It was my first real gig and I didn’t really know who George Lynch was. But when I played with him, I understood why he’s so great.

I think not having access to that world showed in my playing. I didn’t sound like every other bass player coming off the Sunset Strip – I wasn’t just playing the straight eighth-note thing that was happening in Dokken. I didn’t look at that gig like I’m sure other guys looked at it.

Did George give a lot of input into your rig?

I’d been turned on to the Kubiki bass. Philip Kubiki, God rest his soul, was a genius. He made this incredible bass which looked a bit high-tech for a rock gig, but I it played so great. That was my cornerstone, and I had an old Fender P-Bass.

But George quickly taught me about endorsements! As soon as I got the gig, I must have called seven bass amp companies and had them send me stuff. I quickly found that Ampegs sat perfectly with what I was trying to do.

After we did Wicked Sensation I was like, “I need a touring rig.” I had them send out stuff for my wall of a backline – but when the tour was over, I sent all the gear back, which shows my ignorance at the time! They were like, “Nobody ever returns anything. You’re like the only guy!”

The original version of Lynch Mob quickly broke down. What happened?

We were on tour with guys like Jeff Tate from Queensrÿche and Tom Kiefer from Cinderella – consummate pros. They don’t miss a note ever, but Oni Logan would take a while to warm up onstage. I don’t think he warmed up before gigs so he struggled for the first couple of songs. George was like, “I’m not waiting until this guy learns how to sing,” and that was that.

I always told George: ‘We hire amazingly talented people. Just play guitar. You gotta get out of your own way’

You stuck around for another album before departing.

George and I did the lion’s share of interviews when we did press. We’d do like 10 or 12 a day to promote a record. The first question to George was always. “When are you going back to Dokken?” George would say, “No, this is a band. I love being in Lynch Mob.”

But when he fired Oni, and we got Robert Mason to sing on the second record, it was a totally different vibe. George found problems with Robert and wanted to get a third singer. I was like, “If you do a third record with a third singer, it’s gonna look like it’s your solo project until you go back to Dokken.”

I was like, “You have two choices in regards to me. One is to get Oni back, get him vocal lessons, and deal with that. The other is to keep Robert and address the issues that bother you.” I joined because it was a band and an equal split. It wasn’t a hired gun situation, but here he was changing singers like he was changing socks.

But you hooked back up with George in the late ’90s.

That was supposed to be a George Lynch solo album. I was visiting my friend in the A Room of a studio. My friend was like, “You know who is in the D room? George – it’s a solo record. You wanna play on it?” I agreed with it being a George Lynch solo album. Then Robert ends up singing on it and it’s a Lynch Mob album.

I still own a third of the Lynch Mob name because after the issues with Oni were resolved, it went back to a four-way ownership to this day. So I was like, “If you’re gonna call it a Lynch Mob album, I’m entitled to a cut. I’m not just gonna get an amount of dollars to play bass.” The whole thing was weird, but we toured until things fell apart with George, as usual.

When we did the second album he was re-editing the video and redoing the artwork, and I was like, “What the hell are you doing? You’re not an art director! Put your ideas in and have them run with it. We hire amazingly talented people to do this, George. Just play guitar. You gotta get out of your own way.”

I used to tell him that all the time – so it’s funny that, in an interview I just saw, he said something like, “I probably would be better off if I just played guitar!”

You started working with Ace Frehley in 2006. What was he like, having just gotten sober?

When I met Ace I was 11 years sober. We talked a lot about that, worked through that a lot, and started going to meetings. He was really going for it, and I was proud of him for how he handled it. I was introduced to him by a friend of mine, Frankie Gibson, who’s in the Hells Angels.

I was more than just Ace’s bass player. You get a target on your back because everybody wants to be the guy Ace turns to

I went up to the house with a bass. He was in his studio and said, “Let’s play – just plug into that Marshall over there.” It was the red Tolex Marshall he used on the Destroyer tour. Another friend of his, a truck driver called Jeff, was there, too. Ace was like, “Jeff’s gonna play drums.”

I was like, “Great! The first time I’m playing with Ace Frehley, and I’m jamming with a truck driver and playing through a guitar amp!” But it turned out great and we became super-close friends. I was lucky to be brought into his immediate circle of friends – not just music, his real circle.

Many people don’t realize you were instrumental in Ace relaunching his solo career.

He was like, “I wanna do another solo record.” I was like, “I think you should – but I seriously think we should go out on a run before we try to record; get your live chops up and get fierce again.” We put a band together with Scot Coogan and Derek Hawkins, and that was the beginning of that run.

After that two or three-week run, we went in and started working on Anomaly. Ace was like, “I want you to co-write with me,” but I was like, “Honestly, I don’t wanna co-write. I don’t think your fans want to hear what I have to say. You haven’t made a solo album in years. They wanna hear where your head’s at.”

How did you put the music together for Anomaly?

He had all these dictaphones he’d used on the Kiss farewell tour for licks and stuff. We’d find a great verse and put it on a dry-erase board until we could pair it up with another verse. Once we had 10 or 12 pairs that we thought were really good, we brought Anton Fig in and started jamming.

Ace’s second act as a solo artist took off after that. You stayed with him until 2015. Why did you leave?

There’s so much stuff when you’re with Ace; and I was more than just the bass player. I was his friend. You get a target on your back because everybody wants to be that guy who Ace turns to.

I always told him, “The term ‘ex-Kiss guitarist’ opens up a lot of doors, but with that comes the burden of the greatest live rock show ever. You’ve gotta give your fans a show.” I came up with the blue plexiboard baffle boards on the amps, and the big backdrop with the lasers, and the walk-on voice saying, “Your mission, should you choose to accept it…”

Ace was all about it. He loved it, was watching his weight. But a lot of the change had to do with when he started going with Rachel Gordon.

After you left Ace’s band in 2015, you joined Jake E. Lee’s Red Dragon Cartel.

Jake’s gone through so much physically and emotionally after losing Ozzy and getting shot. His world could go two ways

They’d done their first record, and Greg Chaisson had come down with throat cancer, so Jake needed a bass player. My son was the best man at Jake’s wedding. We were sitting on my porch when they were on the phone, and my son said, “Jake wants to know if you wanna play bass with him.”

I was like, “Totally. I’ll do it tomorrow – what do you want me to learn?” That’s just how it goes; I was blessed again to play with another gifted musician. Jake a total musical guy who just happens to be a phenomenal guitar player. I grabbed the gig as hard as I could.

Have you considered why you always seem to end up beside such great but enigmatic guitar players?

I am notoriously known for being brutally honest, even at the risk of losing my gig. Ace loved it because he was surrounded by people who’d say he could do no wrong – they’d just ‘yes’ him to death. I never did that. They want the truth because they wanna know if the direction is right.

I’ve always put my guitar players first, before my own personal gains. With Ace I’d say, “What’s the best thing for his career right now? What should he be doing?” It’s the same with Jake: I put him first. Every once in a while, he’ll ask me what I think, but it’s his band.

And Jake knows very well how he wants to represent himself, so I just wanna help him get his music out to the people in the manner that he’s hearing it. Anything that Jake wants to do, I’d love to be a part of. I’m honored to be his friend, and even more honored to be the guy that he wants to look over to on stage right.

What’s next for you?

Jake’s gone through so much physically and emotionally after losing Ozzy and getting shot. So, his world, I think, could go two ways – he’ll let the music fly out, or not. It’s up to him.

I’m kind of shaken up too. He got shot a year ago, almost to the day that Ace died. And I lost Ace, who was really dear to me. Heaven forbid anything happens to Jake. So, I’m going out there next week just to sit next to him at a bar and catch up.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.