Queen of the Stone Age's Josh Homme Talks New Album, 'Villains'

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When it was announced that Villains, the new album by Queens of the Stone Age, was going to be produced by pop renaissance man Mark Ronson (Adele, Bruno Mars), logic dictated that he would chisel away at the band’s quirky edges.

Queens guitarist and chief conceptualist, Josh Homme, dismisses the notion with a wave of his hand. “There’s this perception that there’s no musical overlap between us and Mark, but, in reality, there’s a stunning amount. We wanted this album to be tight like an early ZZ Top record, and he is so beat-centric, we knew he would help us keep the rhythm section tight and dense.”

Homme’s instincts proved to be correct. Far from being a soulless slice of modern pop product, Villains is infused with an almost old fashioned sense of rock and roll exuberance and devilish mischief.

The fierce robot boogie of the album’s inescapable first single, “The Way You Used to Do,” captures the overall spirit of the album, which manages to reference oldies but goodies like Chuck Berry and Little Richard while still sounding fresh, funky and futuristic.

“I was watching this wild footage of Jerry Lee Lewis from one of his first performances on television during the early Fifties, and he was really putting on a show,” says Homme. “He was going into fits and the shakes while he was singing and playing the piano, and basically encouraging the audience to do the same. The kids were totally losing it. Early rockers like Jerry, Elvis and Little Richard were so radical for their time, I could just imagine parents saying, ‘These guys are villains—this has to stop!’

“That is the punk rock infiltration that I’ve always desired. I have no interest in fitting in or playing nice. My interest is in when you’re revolting against your parents—or if you’re just plain revolting and a sick individual—you come to me.”

Rock and roll subversion is rarely accomplished alone, and Homme has amassed a pretty impressive team of henchmen to help him on his mission. It’s not an overstatement to say Queens of the Stone Age features three of the most creative guitarists in rock music.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

In addition to the innovative frontman, the current lineup includes Troy Van Leeuwen, a respected session musician who also moonlights with Tool’s Maynard Keenan in A Perfect Circle, and Dean Fertita who plays with Jack White in the Dead Weather (see sidebar). So, how do the three make room for all the side projects and still stay focused on the mothership?

“I think the way you live your life has such a massive impact on how long you do your art,” says Homme. “I’ve really staked everything on the fact that music is my religion and my philosophy. It’s how I explain myself when it’s difficult, it’s how I teach my kids, and how I live. I want the guys that are in Queens to unequivocally understand we’re here because we want to be, not because we need to be. So, everyone is encouraged to go do other things, and pick up as much knowledge as they can, so they can bring it home so we can pick through it and get inspired.”

As you will see, there is plenty in Villains to get inspired about. The trio brings a whole new bag of guitar licks and sonic strategies to the band’s already super distinctive sound. In the past, Homme has been reluctant to talk specifics about his sound. But clearly a new spirit of openness pervades his music, and during our conversation, he decided to share a few of his most interesting and provocative ideas.

I really enjoyed the almost uplifting rock and roll attitude on Villains. It’s “let’s have some fun and break some rules,” as opposed to “fuck you, I’m gonna go and shoot some smack.”

JOSH HOMME I like the idea of putting an accelerant on somebody who is thinking, This is who I really wish I was, and this is what I really want to do. Saying “fuck you” is lame and boring. That’s uniting over what you don’t like. It’s too easy, and I have no interest in that.

For me, playing music is an escapism worth its weight in gold, and trying to do it in an artful manner is totally everything, man. My grandpa used to always say, if you can’t outsmart them, out-dumb them, and I feel like my calling is to out-stupid everybody.

That’s a good calling! On the cover of the album I noticed the devil is sitting next to you. He’s covering your eyes, but you’re seeing right through him.

Yeah, man. Everyone feels like they’ve got the devil on their back, or everyone is worried about the devil. But what if that’s your good buddy?

One of the roles of the devil is to go against the grain, which is essential to good rock and roll.

Totally. I think I’ve always felt like if everyone is doing it, how good could it be? There’s only a few instances of things that we all agree on, like Coca-Cola, and maybe like, two other things. On a very fundamental level, whatever bothers a lot of people is a really great place to start, especially if you do it with a nod and a wink. I think for me, that devil is about cutting loose. Life is too short to let fear drive. Now is all you’re ever going to get.

Are you a realist or an optimist?

Both. The realist has a bit of disdain for humanity. The optimistic side, however, believes in truth, to strive for something, to have a faith, and my faith is in rock and roll. My religion is in rock and roll. That’s how I question rules, and that’s how I say: you should think for yourself. That’s how I say: if you don’t make your own plans, you’re part of somebody else’s, and I simply refuse to do that. Defiance looks beautiful no matter who wears it.

Speaking of defiance, you recently recorded an album with Iggy Pop, one of the ultimate rock rebels. What was that like?

Doing Iggy’s record, Post Pop Depression, was the single coolest thing I’ve ever been allowed to be part of. It was a total recharge. It left me feeling like, “Let’s go get ’em, boys!” I love Iggy so much because I really try my best to live in the third truth—you know, yours, mine and what actually happened.

I think Iggy has been living in the third truth his entire life. He wrote this thing for me about what happened during the recording of his solo albums with David Bowie, The Idiot and Lust for Life, and it was so beautifully written because it was completely honest. You just read it and you go, “He never tries to take credit for anything that isn’t his. Nor is he trying to doll up what he did do.” It was just very matter of fact.

Let’s talk some guitar. You regularly express your admiration for loose punk rock bands like Black Flag, the Cramps or the Stooges, but your signature sound is often this super tight, sort of buttoned-down thing. Is there a dichotomy there?

No, I don’t think so, because the lesson of punk rock is to do your own thing. If I’m influenced by Black Flag’s Greg Ginn, it’s not to be Greg Ginn. It’s to find who I am in this grand experiment of life. I’ve always had this un-supply, undemand theory. If I see a repetition of something out there, I just presuppose we don’t need more of that, so I think I’ve always tried to shoot the gap. I’ve always tried to play what I don’t hear.

When did you decide that you were going to try to make a unique statement on the guitar?

I must have been around 13. When I started Sons of Kyuss, my band before Kyuss, we wore our influences on our sleeves and we kind of sounded like other bands, as you do when you’re young. There was a little blowback from that. I think the sting of being embarrassed about imitating somebody at that early age was so powerful, I remember saying, “Never again will somebody say that we sound like somebody else.”

That’s interesting. Usually, when you’re that young, people ask you to cover other bands.

Well, I was fortunate that my little community demanded something unique. It had nothing to do with me. It already existed when I showed up. We lived in Palm Desert, California, and played these outdoor shows powered by a generator that was owned by a guy named Mario Lalli. It was a real DIY environment. And Mario, who we called “Boomer,” in a nice way would just encourage all the bands to find their own voice.

Just like any recipe, that little sprinkle really germinated this attitude of: you must sound like yourself or who do you sound like? Who are you? There were no clubs to play and, in a way, it was incredibly fortunate, because there was no pressure to play Top 40 music and no money to be made.

Honestly, there wasn’t even a way to get out. There were about a thousand windmills at the entrance to the valley I lived in, and it always seemed like we were trapped behind an iron curtain. No way in, no way out—just these spinning blades. So, I never thought I was going to get out. The fact that I’m still doing this is kind of a mystery, but I do attribute the reason I’m still here is that drive to try to find yourself over and over and over.

I never wanted anyone to ever say I sounded like someone else ever again, and that was that. It was as if it was the simplest thing in the world. I struggled to find my voice, but I believed I would accomplish that goal. I never questioned it, and I’m thankful. However, I would not have gotten there on my own without the encouragement of the locals.

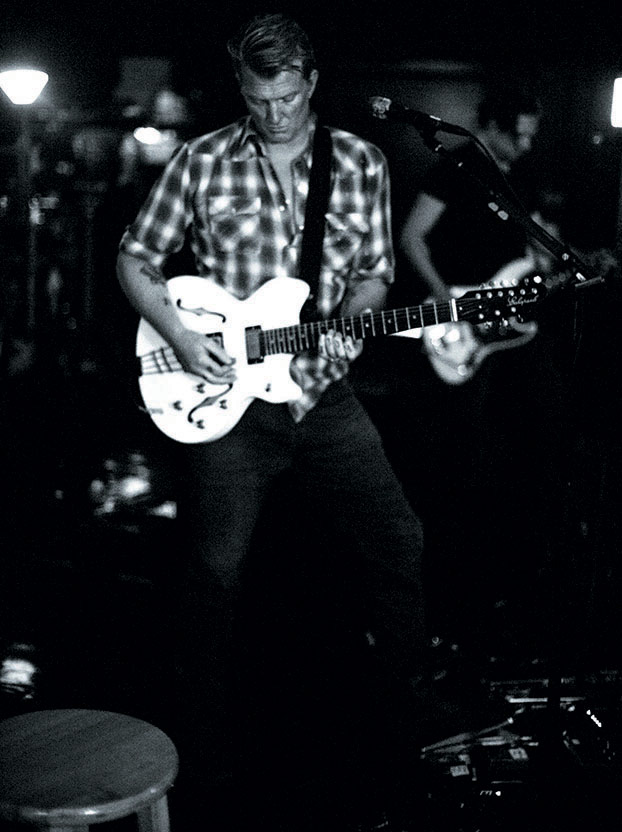

Josh Homme with his custom-made nine-string Echopark Esperanto Z

Before you were in Queens of the Stone Age, you were in Kyuss, who were very influential in the early Nineties. Can you tell me about some of your early guitar experiments in Kyuss?

When Kyuss first formed, there were very few people experimenting with detuning. Back in 1988 or 1989, there was nobody tuning down to B and C like I was—I challenge you to find someone else. I thought it was a good first step toward creating a unique sound. I saw an absence—an un-supply un-demand. Part of it was that I didn’t have a tuner, so I started asking myself, how low can you go?

There are times when I’m drunk, I wonder how much of this detuning business I’m responsible for. I think it’s more than I realize, but a lot of it is not that great, so maybe it’s not the kind of credit I should be looking for. [laughs]

I also used the neck pickup exclusively in Kyuss. I never used the treble pickup, because I thought in the singularity of doing the same thing over and over I would find myself. What’s funny is, I’m using my Kyuss heads on tour with Queens right now, just to change up my shit. It’s funny to go full circle after so many years. The same Ampeg heads that I used when I was 15 still work and sound great! I mean, I guess there’s no reason they shouldn’t.

Playing through Ampeg heads was another interesting choice.

The first amp I ever bought was an Ampeg VT40. They don’t make ’em like that anymore. All that Ampeg stuff is very special. But when it was time not to be in Kyuss, I pretty much left that sound behind.

So we’ve established that you’re a pretty conceptual guy when it comes to your gear. When you started recording Villains, was there something new that you wanted to do or accomplish with your sound?

For years I kept most of my recording techniques a secret, and for some reason, I feel like all of that doesn’t matter now. I didn’t want to take somebody’s journey away by telling them what I did. But everyone has their own secrets in their world, and it’s also cool to share some of them. I’m just going to kind of unload what I did on this record.

This is our seventh record, and I decided it was time to burn some of the ideas that became so closely associated with our sound. On past albums, I really explored using dirty reverbs and mid-range sounds almost to a point of obsession. Looking for ways to get width, and using the darker side of the guitar’s mid-range was not an area people were paying much attention to, so it really appealed to me. I also secretly used solid-state amps in the studio, because I liked the sound of that fast electricity. To my ears, solid state amps just sound like they are charged with electricity.

On this album, I changed my entire approach and decided to experiment extensively with recording many of our guitar parts directly into the board. I wanted the sound of the guitars to be completely vacuous, so that you could hear exactly where the note stopped. Not just where it started, but where it stopped.

I think one of the cues I took was from listening to the old Stooges albums. You can turn them up to 10 on your stereo, and they’ll still sound great because the guitars are not so big that they eat up all the real estate in your stereo and your speakers. I wanted to make something that you could crank the piss out of and it would still sound fantastic.

Now, I’d be willing to bet in that first song, “Feet Don’t Fail Me Now,” that you turned it up in the beginning when all those ambient guitar sounds come in. I kept them quiet on purpose. It’s a dirty trick, because I wanted to lure the listener to turn up their stereo, so when the rhythm guitars finally kick in, it’s so tight and dense it will knock you back, but still sound amazing.

It’s interesting that more players don’t explore the joys of DI (direct input) recording. Some of the greatest—and largest—recorded guitar sounds of all-time were DI. Neil Young’s guitar on “Cinnamon Girl” and Jimmy Page’s guitars on Led Zeppelin’s “Black Dog” are great examples.

Yes. It really gets interesting, especially when you pair that DI tonality with a room amp. The combination is like having the tip of a spear almost poking you in the eye, while the back end is on the other side of the room.

I’ll add that I love a good room sound as opposed to reverb, because reverb goes and goes and goes until it dissipates, but room sound is like saying: the box we play in is this size. It’s finite. When I listen back to our tracks, I always have this picture of what the room size was. You blow smoke in the air and you see the clear walls of this box that things were put in. Does that make sense?

Yeah, most of my favorite albums, like the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main St. and Led Zeppelin IV, were recorded in interesting spaces. I think part of the reason I like them is because the sound describes the complexity of the rooms they were recorded in.

I know that the most important thing to me over the last 10 years has been depth of field. I mean, I certainly use left and right, of course, and this record is extremely hard-panned much of the time. But depth of field is way more important, because I like that you can hear something that clearly sounds like it’s in the back of the room. And I love that occurring at the same time as that DI needle hovers close to your eardrum.

Your playing has to be pretty tight to withstand the microscope of DI recording.

The most difficult song that we’ve ever had to play is our single, “The Way You Used to Do.” It’s a fuckin’ nightmare. I don’t know what it is. To sing and play with that sort of tightness is really demanding.

Why put yourself through it?

I wish I had more choice in what music we played. I do feel like I’m being dragged behind a boat a lot of times, because you play what comes out of your mind. I love that Johnny Cash quote, “I’m not the creator of the music, I’m a deliverer.”

Does your distortion come from the amp, or are you a pedal guy?

I feel like driving the pre-and driving the head is the way to go. I just presuppose that the people that made these heads know what they’re doing and gave a shit. If anything, I might add one of my all-time favorite pedals, the Maestro Parametric Filter, because they add or subtract up to 20db with a wide or tight cue of a wide spectrum of frequencies, all in one go.

There’s an infinite universe in that.

Yeah, that’s why I don’t mind talking about it, because even if you like what we do, and decide to buy one, you still need to find who you are within that universe. The sweep is so wide and variable that it doesn’t really help to know I use it. You still need to discover what you like when you use it. I think it’s the greatest pedal ever.

I understand you’re a fan of big band music, and it shows. Between the fuzz tones and the harmonies, many of the guitar parts on Villains sound like they could be arranged for horns.

I’ve been experimenting with arranging guitar parts to emulate the sound of horns since our first album, Rated R. As I mentioned earlier, I’m really interested in the edge of the sound, and how it stops, and horns do that well. I wanted to see if I could create the same effect with guitars, so I kept pursuing that idea in the Eagles of Death Metal. I wanted the guitars to simulate the baritone trombone and saxophone parts heard in sleazy burlesque clubs. I always kind of thought of Eagles of Death Metal in those terms.

It’s an idea that is also a constant on Villains. How do I make a DI and a little bit of room seem like horns? And how do I do it over and over? And how am I able to layer it? Because when you have three guitars it’s difficult. Everyone needs to be able to be heard, and I think the important thing in Queens of the Stone Age is that it’s about the details. So how do I have three guitars of varying mid-range frequencies all be heard properly?

Combining DI parts, using some depth of field and thinking of the guitars like they were horns helped. Those were the three main questions. Who’s playing saxophone-style guitar? Who’s going DI, and who’s set back but heard clearly? That was our approach to get all three guitars to play nice together. Additionally, we ended up using a lot of keyboards to add to the effect that we were creating a horn section. And, of course it all had to live in that weird 400 to 1k world Queens lives in.

You mentioned that one of your goals for Villians is to make it a dance album. Why was that important to you?

Rock and roll should dance. It always did before, so I don’t see what the fucking problem is. You know, there’s something beautiful about headbanging because it’s like telling everyone else around you, “I don’t care what you think. I like this.”

It’s the same thing with dancing, and that’s why I love it so much. Dancing is like saying, “I don’t care what you think, I’m doing this.” In other forms of music, dance is so acceptable, it’s at the forefront of what it is. I always think of that as being at the forefront of rock and roll, and I’m always surprised when people’s inhibitions and fears, which translates into them thinking they’re cooler than something, gets in the way of something joyous and vulnerable and emotional.

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away Brad was the editor of Guitar World from 1990 to 2015. Since his departure he has authored Eruption: Conversations with Eddie Van Halen, Light & Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page and Play it Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound & Revolution of the Electric Guitar, which was the inspiration for the Play It Loud exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 2019.