“We thought Ramblin’ Man was too country to record. We put it on the album, and it became a hit. Then it more and more became Dickey’s band”: Dickey Betts and Gregg Allman tell the full story of the Allman Brothers Band, one of rock’s greatest groups

In honor of Dickey Betts, who passed away at the age of 80 on April 18 2024, we have been leafing through the archives to unearth some of his best interviews with Guitar World. The following is a comprehensive oral history of the Allman Brothers Band, featuring Betts, Gregg Allman, Butch Trucks, and others who were part of the group's storied career. It was first published in the July 2009 issue.

"The Road Goes on Forever.” Gregg Allman wrote and sang the words in Midnight Rider, and his Allman Brothers Band (ABB) adopted them as a motto, and for good reason: despite the death of two founding members, two breakups and an acrimonious parting with guitarist Dickey Betts, this summer the band is marking its 40th anniversary and doing so in high style.

Warren Haynes and Derek Trucks, who have now played together for nine years in the ABB, form a dynamic, explosive duo that blows away the competition. In that respect, some things in the Allman Brothers Band never change.

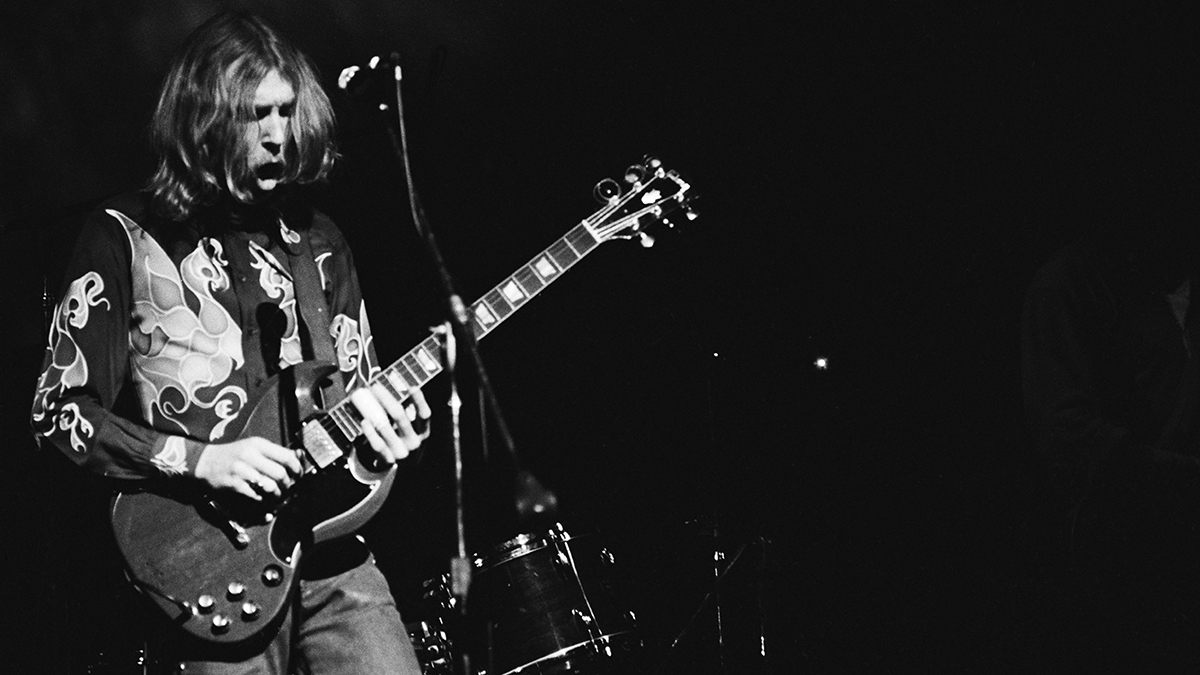

The road for the ABB began in 1968 when Duane Allman, a red-hot session guitarist who had made his mark recording with Otis Rush, Boz Scaggs, Aretha Franklin and others, headed to Jacksonville, Florida, looking to put together a band. His manager wanted a power trio – just like Cream – but Duane reportedly scoffed at the notion, saying, “I ain’t on no star trip.”

It was a revealing statement, for the group that resulted from Duane’s quest for kindred musical souls was anything but ego-driven. The music of the Allman Brothers Band has revolved around group improvisation and dynamics since their self-titled 1969 debut.

Duane’s musical vision and open mind allowed him to ignore protocol and put together a completely unique hard-rocking outfit featuring two very different but complementary drummers (Jai Johanny “Jaimoe” Johanson and Butch Trucks), an inventive bassist who could hold down the bottom end while displaying melodic flair (Berry Oakley), a soulful singer and organist (brother Gregg), and another hot lead guitarist (Betts).

Betts would prove to be a monumental addition, for his participation underscored the band’s adherence to a rule of jazz: that a group needs multiple, equally powerful lead voices to truly generate sparks.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Betts and Allman rewrote the rules for how two rock guitarists can work together, completely scrapping the traditional rhythm/lead roles to stand toe to toe, alternately cutting each other’s heads and joining together for marvelous flights of harmony.

The ABB’s instrumental majesty was grounded in the blues and in the excellent tunes penned by Gregg Allman and Betts. This combination of a unique vision, instrumental superiority and great songwriting has carried the band through four decades. The Allmans pushed on after Duane Allman’s and Berry Oakley’s tragic deaths, reunited after two breakups and, perhaps most shockingly, have performed without Betts since 2000.

What follows is the ultimate overview of the band’s career, an oral history told in the words of the people who lived it.

The beginning of the Allman Brothers Band

Duane Allman met drummer Jai Johanny “Jaimoe” Johanson while working on sessions in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Duane wanted to form his own band, and his manager, Phil Walden, suggested that he create a power trio in the spirit of Cream and the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

Allman targeted bassist Berry Oakley, a Chicago native who was then playing in a Florida band called Second Coming with guitarist Dickey Betts. At Duane’s invitation, Oakley came to Alabama for jam sessions...

Dickey Betts: “The band just sort of happened. It was supposed to be a three-piece with Duane, Berry and Jaimoe. Duane and Jaimoe kept coming and sitting in with Second Coming to get used to playing together, and as we started jamming, something clicked.

“Eventually Duane asked if I’d go with them. When Butch [Trucks] came along one day and jammed with us, it was something special. All of a sudden the trio had five pieces. We all were smart enough to see that each of us was making a contribution to the sound.”

Butch Trucks: “I had played with Gregg and Duane before, and he called me when he came back to Jacksonville. He was jamming with lots of different people. We played, and it just worked. Jaimoe told Duane I was the guy they needed – he wanted two drummers like James Brown had – but I don’t think Duane wanted me in the band.

“I fit musically, but I was a bundle of insecurity, and he didn’t want that. He was such a strong person – very confident and totally sure of himself – and that’s the kind of people he wanted around him.”

Betts: “It says a lot that Duane’s hero was Muhammad Ali. He had Ali’s type of supreme confidence. If you weren’t involved in what he thought was the big picture, he didn’t have any time for you.

“A lot of people really didn’t like him for that. It’s not that he was aggressive; it was more a super-positive, straight-ahead, I’ve-got-work-to-do kind of thing. If you didn’t get it, see you later. He always seemed like he was charging ahead.”

One day we were jamming, going nowhere, so I started pulling back. Duane whipped around, looked me in the eyes and played this lick way up the neck, like a challenge

Butch Trucks

Trucks: “One day we were jamming on a shuffle, going nowhere, so I started pulling back and Duane whipped around, looked me in the eyes and played this lick way up the neck, like a challenge. My first reaction was to back up, but he kept doing it, which had everyone looking at me like the whole flaccid nature of the sound was my fault.

“The third time I got really angry and started pounding the drums like I was hitting him upside his head. The jam took off, and I forgot about being self-conscious and started playing music. Duane smiled at me, as if to say, 'Now that’s more like it!'

“It was like he reached inside me and flipped a switch, and I’ve never been insecure about my drumming since. It was an absolute epiphany; it hit me like a ton of bricks. I swear, if that moment had not happened, I would probably have spent the past 30 years as a teacher. Duane was capable of reaching inside people and pulling out the best. He made us all realize that music will never be great if everyone doesn’t give it all they have, and we all took the attitude that if you don’t do that, why bother?”

Betts: “Duane was a natural leader, and if he got knocked down, you’d feel compelled to do everything you could to get him back up and going again. He and I talked a lot about that and decided that would be the difference in our band as compared to every other band we’d ever been in: when someone falls, instead of talking about him or taking advantage of him, we’d pull him back up. Whenever we needed a leader, someone would step forward and lead.”

Trucks: “One day, the five of us had just played this incredible jam, and Duane went to the door and said, 'If anyone wants to leave this room, they’re going to have to fight their way out.' We all knew we had something great going, but we didn’t have a singer.”

Phil Walden [co-founder of Capricorn Records]: “They had this great instrumental presence but no real vocalist. So Duane called Gregg and asked him to come down.”

Gregg was still living in Los Angeles, having remained there after the breakup of Hour Glass, a band he and Duane had formed and which had recorded for Liberty Records. The records had little success, and Duane returned to the South, “where we belonged,” says Gregg.

Gregg Allman: “I didn’t have a band, but I was under contract to a label that had me cut two terrible records with these studio cats in L.A. They had me do a blues version of Tammy Wynette’s D-I-V-O-R-C-E, which can’t be done. It was really horrible. They told us what to wear, what to play… everything. I hated it, so I was excited when my brother called and said he was putting a new band together and wanted me to join. I was doing nothing, going nowhere.

“Duane said he was tired of being a robot on the staff down in Muscle Shoals [Sound Studio], even though he had made some progress and gotten a little fame from playing with great people like Aretha and Wilson Pickett. He wanted to take off and do his own thing. He said, 'I’m ready to get back on the stage, and I got this killer band together. We got two drummers, a great bass player and a hell of a lead guitar player, too.' And I said, 'Well, what do you do?' And he said, 'Wait’ll you get here and I’ll show you.'

“I didn’t know that he had learned to play slide so well. We were not together for the 11 months after he left L.A. – the only time we were ever apart – and that’s when he really learned to play slide. He sent me a ticket, but I didn’t have any money, so I cashed it in, stuck out my thumb on the San Bernardino Freeway and got a ride all the way to Jacksonville.

“I walked into rehearsal on March 26, 1969, and they played me the track they had worked up – Muddy Waters’ Trouble No More. It blew me away. It was so intense. I got my brother aside and said, 'I don’t know if I can cut this. I don’t know if I’m good enough.' And he starts in on me: 'Oh, you little punk, I told these people all about you, and you don’t come in here letting me down.'

“He handed me the words to the song, all written out. I said, 'Count it off, let’s do it,' and I did my damnedest. I’d never heard or sung this song before, but by God I did it. I shut my eyes and sang, and at the end of that there was just a long silence. At that moment we knew what we had. Duane knew which buttons to push. He kinda pissed me off and embarrassed me into singing my guts out.”

Walden: “Aside from a true vocal presence, Gregg brought these really important foundation songs that the band was really built around.”

Allman: “They asked if I had any songs, and I showed them 22. They rejected them all except Ain’t My Cross to Bear and Dreams and told me to get busy writing. And within the next five days I wrote Whipping Post, Black-Hearted Woman and a few others. I got on a real roll there. Those songs came out of the long struggle of trying so hard and getting fucked by different land sharks in the business – just the competition I experienced out in L.A. and being really frustrated, but hanging on and not saying 'Fuck it' and going into construction work or something.”

Betts: “Berry played a huge role in the band’s arrangements. Whipping Post was a ballad when Gregg brought it to us. It was a real melancholy, slow minor-key blues, along the lines of Dreams. Oakley came up with the heavy bass line that starts off the track, along with the 6/8-to-5/8 shifting time signature.

“Oakley called a halt to the rehearsal and said, 'Let me work on this song tonight, and let’s get back to it tomorrow.' By the next day, he had that intro worked out. When he played that riff for us, everyone went, 'Yeah! That’s it!' Oakley morphed a lot of those songs into something different.”

Breaking through with guitar harmonies

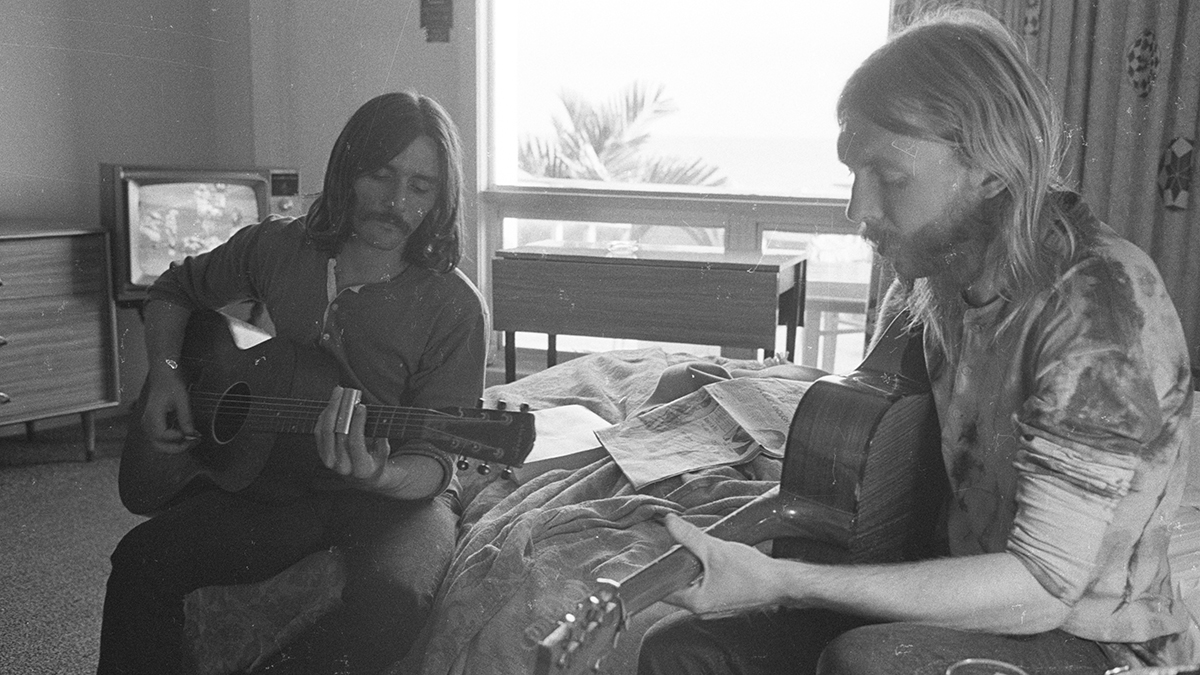

The band’s first real musical breakthrough was the extensive use of guitar harmonies. Betts, with his knack for crafting memorable melodies, generally played the line first. Allman, with his perfect pitch and spot-on ear, picked up anything and created a harmony on the spot.

Betts: “We got those ideas from jazz horn players like Miles Davis and John Coltrane and fiddle lines from western swing music. I listened to a lot of country and string [bluegrass] music growing up. I played mandolin, ukulele and fiddle before I ever touched a guitar, which may be where a lot of the major keys I play come from.

“But I also always loved jazz, and once the Allman Brothers were formed, Jaimoe really fired us up on jazz, which is all he listens to. He had us listening to a lot of Miles Davis and John Coltrane, and a lot of our guitar arrangements came from the way they played together.

“Duane and I had an immense amount of respect for each other. We talked about being jealous of each other and how dangerous it was to think that way, that we had to fight that feeling when we were onstage. He’d say, 'When I listen to you play, I have to try hard to keep the jealously thing at bay and not try to out-do you when I play my solo. But I still want to play my best!'

“We’d laugh about what a thin line that was. We learned a lot from each other. Duane had a strong belief in himself, and he was damn good. I was damn good too; I just didn’t believe in myself the way Duane did.”

Duane and I had an immense amount of respect for each other. We learned a lot from each other. Duane had a strong belief in himself, and he was damn good

Dickey Betts

Warren Haynes: “The Allman Brothers Band is based on the fact that no one onstage can rest on their laurels; you have to bring it. That’s where that fire comes from, and it certainly emanates from the intensity of having two great lead players like Dickey and Duane throwing sparks off of each other.

“Obviously, jazz and blues musicians have been doing this for decades, but I think they really brought that sense that anyone onstage can inspire anyone else at any given time to rock music.”

Allman: “Duane was all about two lead guitars. He loved players like Curtis Mayfield and wanted the bass, keyboards and second guitar to form patterns behind the solo rather than just comping. Duane also loved jazz guitarists like Wes Montgomery, Tal Farlow and Kenny Burrell.

“But the main initial jazz influence came from Jaimoe, and Jaimoe really got all of us into Coltrane, which became a big influence. I brought the blues to the band, and what country music you hear in our sound came from Dickey. We all dug this different stuff, and we all started listening to the other guys’ music. What came out was a mixture of all of it.”

Betts: “Duane and Gregg had a real 'purist' blues approach, but Oakley and I, in our band, would take a standard blues and push the envelope. We loved the blues, but we wanted to play in a rock style, like what Cream and Hendrix were doing.

“Duane was smart enough to see what ingredients were missing from both bands. We knew that we didn’t have enough of the purist blues, and he didn’t have enough of the avant-garde/psychedelic approach to the blues. So he tried to put the two sounds together, and that was the first step in finding the sound of the Allman Brothers Band.”

A new voice on the American music scene

The band moved to Macon, Georgia, and spent countless hours living and playing together, in the process forming a real brotherhood. Their self-titled debut, featuring five Gregg Allman originals and covers of Muddy Waters and Spencer Davis songs, was released in November 1969. It heralded the arrival of a new voice on the American music scene, but few were listening...

Walden: “The first album sold less than 35,000 copies when it was released.”

Betts: “We were just so naïve. All we knew is that we had the best band that any of us had ever played in and were making the best music that we had ever made. That’s what we went with. Everyone in the industry was saying that we’d never make it, we’d never do anything, that Phil Walden should move us to New York or L.A. and acclimate us to the industry, that we had to get the idea of how a rock and roll band was supposed to present themselves.

“Of course, none of us would do that, and thankfully, Walden was smart enough to see that would just ruin what we had. We just stayed on the road, playing gigs and getting tighter and better.”

Allman: “We sure didn’t set out to be a 'jam band', but those long jams just kinda emanated from within the band, because we didn’t want to just play three minutes and be over. And we definitely didn’t want to play nobody else’s songs like we had to do in California. We were going to do our own tunes, which at first meant mine, or else we were going to take old blues songs like Trouble No More and totally refurbish them to our tastes.”

The band’s second album Idlewild South, was released less than a year later. Producer Tom Dowd, who would become an honorary member of the band, helped them expand their palette. Still, the album did only marginally better than its predecessor despite two singles, Midnight Rider and Revival and the debut of Betts’ masterful instrumental In Memory of Elizabeth Reed.

Allman: “When the first record came out at Number 200 with an anchor, and dropped off the face of the earth, my brother and I did not get discouraged. But I thought Idlewild South was a much better record, and when that died on the vine, I thought, 'Damn, maybe we were wrong about this group.'”

Walden: “I doubted myself. It seemed like I had just been wrong and that they were never going to catch on. People just didn’t grasp what the Allmans were all about, musically or any other way. But they kept touring, going across the country, establishing themselves city by city as the best live band around, and building a base.”

Betts: “Duane was bursting with energy; he was a force to be reckoned with. His drive and focus were incredible, as was his intense belief in himself and our band. He knew we were going to make it. We all knew we were a good band, but no one else had that supreme confidence. And his confidence and enthusiasm were infectious. He helped us all believe in ourselves, and that was an essential key to the success of the Allman Brothers Band.”

Allman: “We played 306 nights in 1970, traveling most of the off days. We were in a Ford Econoline van and then a Winnebago. That kind of schedule puts a lot of wear and tear on your ass, but we were sure getting better. We simply realized that we were a better live band than studio outfit because we were always ready to experiment – offstage as well as on, I may add. And the audience was a big part of what we did, which couldn’t be duplicated in a studio. A light bulb finally went off: we needed to do a live album.”

At Fillmore East

The Allman Brothers’ marathon live shows were certainly drawing raves. Onstage, the group combined the Grateful Dead’s go-anywhere jam ethos with a far-superior musical precision. Under the circumstances, a live album was an obvious choice. The result was the double-album At Fillmore East. To cut the album, the band played New York’s Fillmore East for three nights on March 11, 12 and 13 of 1971.

A mobile 16-track recording studio was parked on the street outside the theater, with Dowd and a small crew set up inside. Things went smoothly on the first night until the band unexpectedly brought out sax player “Juicy” Carter and harmonica player Thom Doucette.

At Fillmore East’s sales numbers were strong from the start, and the band kept on the road. Duane’s constant faith seemed to be paying off. But things were far from calm...

Tom Dowd: “One of the guys asked me how to mic the horn, and I thought he was joking. They started playing and the horn was leaking all over everything, rendering the songs unusable. I ran down at the break and grabbed Duane and said, 'The horn has to go!' and he went, 'But he’s right on, man.' And I said, 'Duane, trust me, this isn’t the time to try this out.' He asked if the harp could stick around, and I said sure, because I knew it could be contained [on the recording] and wiped out if necessary.

“Every night after the show we would just grab some beers and sandwiches and head up to the Atlantic studios to go through the show. That way, the next night, they knew exactly what they had and which songs they didn’t have to play again.”

Betts: “We just felt like we could play all night and sometimes we did. We could really hit the note. There’s not a single fix on Fillmore. Everything you hear there is how we played it.”

Dowd: “That album captured the band in all its glory. The Allmans have always had a perpetual swing sensation that is unique in rock. They swing like they’re playing jazz when they play things that are tangential to the blues, and even when they play heavy rock. They’re never vertical but always going forward, and it’s always a groove.

Fusion is a term that came later, but if you wanted to look at a fusion album, it would be Fillmore East

Tom Dowd

“Fusion is a term that came later, but if you wanted to look at a fusion album, it would be Fillmore East. Here was a rock and roll band playing blues in the jazz vernacular. And they tore the place up.”

Betts: “There’s nothing too complicated about what makes Fillmore a great album. We were a hell of a band, and we just got a good recording that captured what we sounded like. I think it’s one of the greatest musical projects that’s ever been done in any genre. It’s an absolutely honest representation of our band and of the times.”

Jaimoe: “Fillmore was a particularly great performance and represents what a typical night was like for us. That’s what we did!”

Walden: “Atlantic/Atco rejected the idea of releasing a double-live album. [Atlantic executive] Jerry Wexler thought it was ridiculous to preserve all these jams. But we explained to them that the Allman Brothers were the people’s band, that playing – not recording – was what they were all about, and that a standard-length phonograph record was confining to a group like this.”

Allman: “All of a sudden, here comes fame and fortune. In a three- or four-week period, we went from rags to riches, from living on a three-dollar-a-day per diem to 'Get anything you want, boys!'”

Butch Trucks: “Duane was strong, confident and honest. He wanted to experience everything, good or bad, and when he realized that what he was doing was negative, he would stop. I saw him experiment with every drug there was, but once he realized it was affecting his music, he stopped and never did it again. And that included heroin. He never stuck a needle in his arm, but he would snort it.

“One night in the summer of ’71, in San Francisco, he came to my hotel room and jumped in my face. He said, 'When Dickey gets up to play, the rhythm section is pumping away, and when I get up there you’re laying back and not pushing at all.' I looked him dead in the eye and said, 'Duane, you’re so fucked up, you’re not giving us anything.' He looked me in the eye, walked out the door and never touched the stuff again.

“I think he knew I was telling the truth, and that’s what he wanted to hear. He needed someone to tell him what he already knew, and it was one of the few times I had the balls to get in his face.”

Dr. John [keyboardist and peer of the Allmans]: “Duane was so special, man, a real sweetheart. He was out there, past left field, but he was as sweet as they come. In some way, Duane knew he lived on the edge. I don’t think he had a death wish, but he knew that he was pushing it, that his lifestyle wasn’t necessarily compatible with life. I remember being in Miami with him, and he got an Opel because that was supposed to be the car you couldn’t turn over, and he just wanted to prove that he could flip it.

“We were there doing a session with Ronnie Hawkins, and the three of us was havin’ a drink with a hurricane comin’ up, and he said something like, 'If I’m not here, could you look after my brother?' It wouldn’t have been his style to be that direct, ’cause he wasn’t that clear about anything. But he knew he might not be around for real long, and we both understood that’s what he was saying. It was eerie, man.”

Tragedy strikes

At Fillmore East was certified Gold on October 14, 1971. 20 days later Duane Allman was killed in a motorcycle crash in Macon, while on a break from recording the band’s followup album, Eat a Peach, in Miami. He was one month shy of his 25th birthday and had been playing slide guitar for less than four years.

Allman: “We didn’t enjoy our [breakthrough with] Fillmore for long. A lot of the initial impact of the joy was absent because of the heavy tragedy that happened to my brother. We worked so hard, so long, to get there, then, bam, he was gone.”

Betts: “We thought about breaking up and all forming our own bands. But the thought of just ending it and being alone was too depressing.”

Scott Boyer [musician close to the Allmans]: “Gregg was extremely tore up, which is only natural. Actually, every musician in Macon was pretty down. We couldn’t believe Duane was gone. It was inconceivable how someone that alive could be dead. He was a central figure for all of us, and, of course, he was the central figure for Gregg. They were extremely close.”

Trucks: “It was just unacceptable that he was gone. Unfathomable. We thought about quitting because how could we go on without Duane? But then we thought, How could we stop? We decided to take six months off, but we had to get back together after a few weeks because it was too lonely and depressing. A musician gets his emotions out by playing music. We were all just devastated, and the only way to deal with it was to play.”

The band had already recorded several tracks for Eat a Peach. These included Little Martha, a gorgeous acoustic duet between Betts and Allman, which was the only music Duane ever officially wrote, and Blue Sky, Betts’ country rock song, which features a stunning dual-guitar break. Just weeks after Duane’s death, the band recorded four more outstanding tracks, including Melissa, Betts’ instrumental Les Brers in A Minor and Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More, Gregg’s defiant response to his brother’s passing.

The double-album release was rounded out by more great tracks from the Fillmore shows, including the 34-minute Mountain Jam, One Way Out and Trouble No More. Eat a Peach was an instant classic, but as the band returned to the road, they felt the absence of their guiding light profoundly.

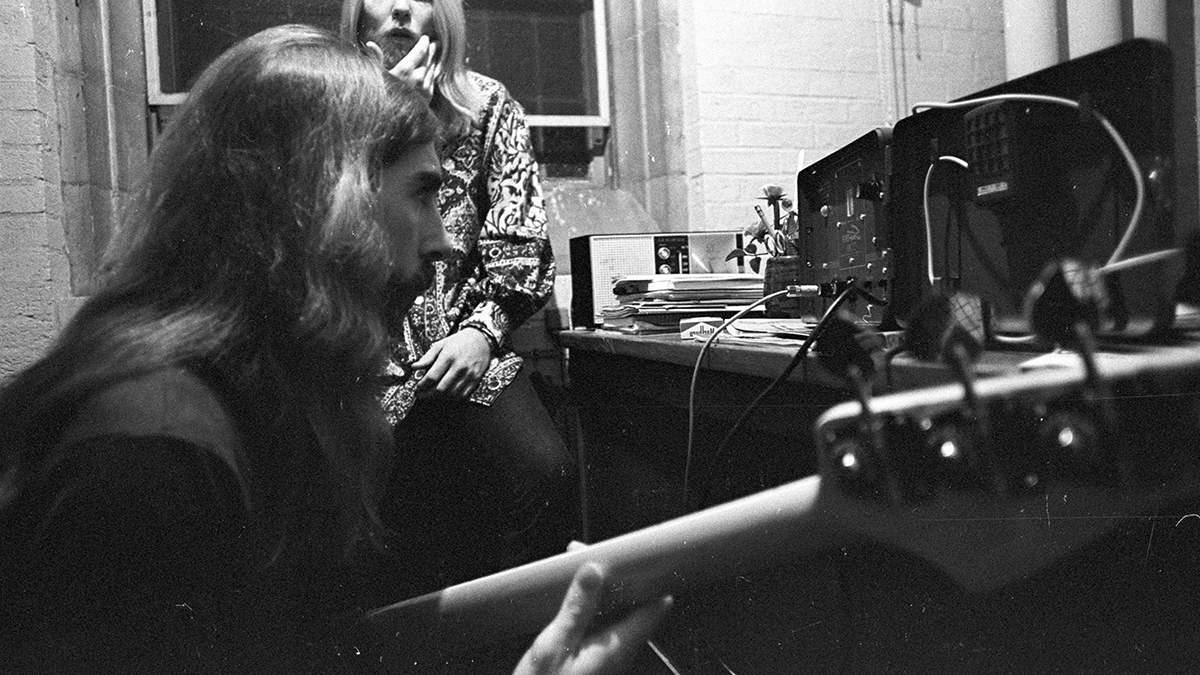

Allman and Betts worked constantly, recording solo albums even as the ABB began cutting Brothers and Sisters, their follow-up to Eat a Peach, featuring the hits Ramblin’ Man and Jessica. Pianist Chuck Leavell, who had played on Gregg’s Laid Back solo effort, became a crucial new member of the ABB.

Trucks: “We played gigs as a five-piece, but there was a big hole there. How could you not miss such a personality? But we were up there playing the music that he started. We were playing for him, and that was the way to be closest to him. Duane had put this thing inside all of us and we couldn’t walk away.”

Chuck Leavell: “I was asked to work on Laid Back. The Brothers were recording Brothers and Sisters at the same time, the sessions often overlapped, and we all hung around the studio an awful lot. Before I knew what was going on, I was working on that, too. Things were pretty loose.”

Betts: “We did what we had to do. We were forced to bring new people into the band, and replacing Duane with another guitar player was out of the question. We added Chuck Leavell, and it changed the whole direction of the band – a little too much in the end. It wasn’t by any means all bad change; Jessica wouldn’t be the same tune without Chuck, who is just a great, great player. But the band headed off the path of what the original players had envisioned from the first day.

Trucks: “Dickey took over. While Duane was around we were a blues-based band and we added John Coltrane and Miles Davis to the mix. After Duane died, we started heading in a country direction, because that was Dickey’s background.

We all thought Ramblin’ Man was too country to even record. We put it on the album, and it became a hit. Then it more and more became Dickey’s band

Butch Trucks

“We all thought Ramblin’ Man was too country to even record. We knew it was a good song, but it didn’t sound like us.

“We went to the studio to do a demo to send to Merle Haggard or someone, and then we got into that big long guitar jam, which kind of fit us, so we put it on the album, and it became a hit. Then it more and more and more became Dickey’s band.”

Shortly into sessions for the new album, tragedy struck the band again. On November 11, 1972, Berry Oakley was killed in a motorcycle crash, just two weeks past the one-year anniversary – and only three blocks from the location – of Duane’s death.

The band added Lamar Williams and finished Brothers and Sisters, which was released in August 1973. It became the Allman Brothers Band’s first Number One album, thanks in part to the hit single Ramblin’ Man, as well as Jessica and Southbound, which both remain band staples.

The Allman Brothers were just about to find their greatest success, but the band was reeling from the impact of so many changes.

Betts: “After Duane died, it was still very dynamic at first, but it just slowly slipped away. And then we lost Berry, and it was very hard to continue. I’m not weighing Duane’s loss against Berry’s loss, but losing two members was just so tough. Berry was also a huge personality.

“He was the social dynamics guy: he wanted our band to relate to the people honestly. He was always making sure that the merchandise was worth what they were charging, and he was always going in and arguing about not letting the ticket prices get too high, so that our people could still afford to come see us.”

Trucks: “Brothers and Sisters took off and we became big rock stars and were the number-one band in the country, but the music became secondary to everything else. Of course, having all these gorgeous women falling over us and all this stuff was fun. It was a big party. But the music became secondary.

“Eventually, we all realized that the drugs and everything else had become so destructive that we were killing ourselves, and it got to where we didn’t like each other. We just couldn’t keep it going.”

Betts: “The whole thing probably wouldn’t have even lasted as long as it did if it weren’t for Chuck Leavell. He was just such a strong player.”

Breakups and reunions

By the time the group’s live effort Wipe the Windows, Check the Oil, Dollar Gas was released in 1976, the Allmans had disbanded. They reunited in 1978 with guitarist “Dangerous” Dan Toler, who had played with Betts in his band Great Southern, and released Enlightened Rogues in early 1979. But some indefinable spark was missing, and the band’s music grew weaker over the course of two uncompelling albums recorded for Arista: 1980’s Reach for the Sky and 1981’s Brothers of the Road.

Dowd: “We tried very hard to reach the classic sound on Enlightened Rogues. We worked our fingers to the bone.”

Trucks: “That band just didn’t work. The chemistry wasn’t there. The only reason the first album [Reach for the Sky] was half successful was that Tom Dowd worked so hard.”

Betts: “We just could not measure up to the original band. Even when we had some great players, there was a pull, a tension. The unity was lacking. And we didn’t have another slide guitarist, so I played slide, which I never really liked, and which also took away from the sound of my guitar.”

Trucks: “At Arista, [label founder] Clive Davis tried to turn us into Led Zeppelin and brought in outside producers, and it just kept getting worse.”

Betts: “When the music trend started turning away from blues-oriented rock toward synthesizer-based dance music arrangements, the record company started to dictate what type of record we could make, and we got caught up in that whole thing.

“A guy like Eric Clapton has a way of being a chameleon, of finding songs that keep him in the forefront and surviving through times when the kind of music he loves to play isn’t popular.

At Arista, Clive Davis tried to turn us into Led Zeppelin and brought in outside producers, and it just kept getting worse

Butch Trucks

“The Allman Brothers Band was never able to do that. We either sounded like our band or we didn’t. The band never really had anything special when we’re not able to do the instrumental jams and improvisation – which were kind of taken away from us for a while. We were even asked not to mention southern rock in an interview or wear hats onstage.”

Allman: “Arista tried to throw us into doing something that we weren’t. The whole music scene of the Eighties just wasn’t conducive to our music at all. We cut two albums and…it was very frustrating. Embarrassing, really.”

Betts: “We broke up in ’81 because we decided we better just back out or we would ruin what was left of the band’s image.”

Throughout the '80s, the members of the Allman Brothers Band toured with different groups. By the end of the decade, the new classic rock radio format had given the Allman Brothers’ great songs renewed prominence, while the 1989 four-album Dreams box set shone a light on their legacy.

Epic Records, which had both Gregg Allman and Dickey Betts under contract, suggested an ABB reunion. The band took to the road with two new players: guitarist Warren Haynes, who had played with Betts for several years, and bassist Allen Woody, who was hired after open auditions.

The Allman Brothers band returned to the studio with Dowd and produced 1990’s Seven Turns, a surprisingly strong comeback. They followed it up with Shades of Two Worlds the following year, then showed their mettle on two live releases and 1994’s Where It All Begins.

Betts: “Classic rock stations really brought the Allman Brothers back, and Stevie Ray Vaughan opened the whole thing up. He just would not be denied and kept making those traditional urban blues records. He just shoved blues down people’s throats, and they got to likin’ it. He just kicked the door open.

“I remember how beautiful it made me feel to hear him on the radio. And I think that a lot of other people felt the same way and were more ready for us to reappear. The Who were touring, and the Stones were getting ready to hit the road. CBS wanted us to get back together because everyone else was doing it. But it wasn’t nearly that simple. We knew we had to go slow, to see if the music was up to snuff and whether we really wanted to do it.

“Seven Turns was a tough album, because we knew that the critics would use it to determine whether we should be back playing together or should have remained broken up. We were under pressure to show that we belonged back together. We never doubted it, but the album simply had to prove that.”

Allman: “To me, there wasn’t a lot of pressure on Seven Turns. It was more of an adventure: let’s see what a few years away from each other did for us. And it was good. We needed a break from each other and came out swinging.”

Betts: “There were a variety of reasons that group worked better than some of the others. For one thing, Warren and Allen knew what we were after. They had studied us for years and understood where they fit into the band. And Warren was the first guitarist who came along since Duane who could really stand on his own and play off of me, which is the basis of our whole style.

“He’s a great player and has his own style, so he was not pulled into constantly trying to sound like Duane, though he was plagued with that comparison from day one.”

Haynes: “I had listened to the Allman Brothers since I was nine years old, and I studied that music hard. But once I joined the band, some of the things that they were doing became obvious to me in a way that I could never have figured out as a listener.

“At the beginning I was constantly drawing the line about how much of Duane’s influence to show. It was always left up to me how much of it to insert. They’ve always said, 'Play like you. That’s what we hired you to do.' They definitely allowed me the creative freedom to interject my own personality into the music. Not a lot of bands would do that.

“The Allman Brothers were very open minded about that from the very beginning, because that music was built on the foundation of two guitar players working equally together. If you don’t have that, the music suffers.”

Allman: “From the start, Woody and Warren were full-on Allman Brothers, much more so than some people in earlier incarnations. And that made a big difference.”

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

The Allman Brothers Band were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in January 1995. Gregg Allman remembers the event primarily for what he didn’t do – speak coherently – and how it prompted him to sober up.

Allman: “The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame night is what made me finally clean up. I could barely stand up. I meant to say something about my mother and something about Bill Graham. I meant to say a lot of stuff, and I was too gone to say any of it. All day I tried to be really cool about it, but you just cannot. Later, I watched it on TV, and I was mortified.

“That’s what it took for me to get serious about cleaning up. I didn’t go into a rehab. I hired a private nurse to come in to my house in Novato, California. It was a real rough year, but I sure needed it.”

Departure of Dickey Betts

In 1997, Haynes and Woody left the Allman Brothers Band to pursue their power trio, Gov’t Mule, full time. The band replaced them with bassist Oteil Burbridge and guitarist Jack Pearson and soldiered on with a somewhat quieter, more groove-based sound.

In ’99, Pearson departed and was replaced by Derek Trucks, Butch’s then-19-year-old nephew. One year later, Trucks had already begun to establish himself as a dynamic soloist when, after a brief and shaky spring tour, the band members told Dickey Betts that they would no longer perform with him.

Trucks: “We did not fire Dickey. We wrote him a letter and said we would not tour with him that summer, but dates were already booked and we were going to honor them with someone else. He responded by hiring a lawyer and suing us, and then we sat there in arbitration for weeks. After all the stuff that was said, there’s no way we can work together again.”

Betts: “I knew that there was tension that had to snap, but I had no idea that it was all on me. I thought something would snap that I would have to take care of, like I had so many times before. I called Gregg, and he said, ‘I don’t owe you an explanation. Listen to the fucking tapes [of the spring tour],’ and hung up.”

It had ceased to be a band – everything had to be based around what Dickey was playing

Gregg Allman

Allman: “We made this decision for a simple reason: the music was suffering. It had ceased to be a band – everything had to be based around what Dickey was playing. I was actually getting ready to walk because I could not stand the situation anymore. I even wrote a letter of resignation. Then I spoke with Butchie [Trucks], and he was thinking the same thing, and we just realized that was crazy.

“After so many years of drinking and abusing drugs, I finally cleaned up, and I didn’t want to waste one minute of time for the rest of my life. God, I had wasted enough time! I was finally sober. That monkey was off my back. I even quit cigarettes and I quit it all at once.

“I realized I was on death’s doorstep, and I was thankful to God that I had woke up before all the innings of the game were over. I wasn’t gonna put up with nothing – not another minute of bullying or negativity mixed with music. I’d quit music first, and I don’t think I’m ever gonna quit music.

“It’s definitely hard to maintain a band for so many years for many, many reasons. It’s a give-and-take thing, so similar to a marriage or relationship. You have to maintain a balance or everyone suffers.”

Betts: “It was a real family for so long, and we took care of each other. We took care of brother Gregg, and we took care of brother Butch. It’s amazing that we kept going for 30 years with our two big brothers gone. Then it finally flew apart, and it’s kind of okay. I just happened to be the one that it came down on.”

Guitarist Jimmy Herring joined the ABB for their 2000 summer tour. That August, Woody passed away. Allman called Haynes and extended an offer to perform with the group. Unsure of the Gov’t Mule’s future, Haynes accepted and returned to the Allmans the following March for their annual residency at New York City’s Beacon Theater.

He was billed as a special guest, with no guarantees of what would come next. Haynes and Derek Trucks immediately struck an explosive chemistry, which has continued to deepen over the years. Subsequent to Haynes rejoining the band, the ABB released Hittin’ the Note, their last album of new material, in 2003.

Haynes: “No one knew what I was going to do, including me. I had some concerns about coming back to the Allmans, but Gregg’s phone call was really a saving grace, because I needed to stop wallowing in my misery over Woody’s death and plunge into something. I agreed to play some shows and see if the vibe and the music were good.”

Trucks: “Warren was the guy we needed. I’m not sure we would have continued at all if Warren hadn’t taken the job. I simply can’t imagine who else could have done this gig.”

Haynes: “The band has certainly undergone a strange transformation, but in a very positive way. This particular unit plays great together and probably listens more intently than any band I’ve ever been in, which makes it easy to go some place different every night. And that is the goal: to take this venerable institution someplace new without ever losing touch with the four-decade tradition that makes the Allman Brothers Band something really special.”

Derek Trucks: “It’s just an underlying respect for the band’s history and legacy, which Warren and I both share. You want to make music that can stand on its own, and you want to be able to listen to it in 20 years and be proud. It’s a big obligation to make music as the Allman Brothers, and both of us want to make sure that the name is back in a very positive way. You don’t want to be the guy who let it slip!”

Allman: “Where does Derek come from? I don’t know, but if you believe in reincarnation...”

Trucks: “I can’t explain Derek and don’t even try. I’ve been playing with him nine or 10 years now and I still have no idea what he is going to do. Every time he plays something it’s a surprise, and it’s astounding what that says about his musical depth. I think he is what Duane may have become if he had more time. Remember, Duane was 24 when he died and had only been playing slide for a few years.”

Allman: “Probably not a day goes by that we don’t talk about Duane. It’s almost like he’s with us. Sometimes when I’m onstage I can feel his presence so strong, I can almost smell him. It’s like he’s right there next to me. For years I thought that my brother really got shortchanged because he never quite got to see what he had accomplished, but I’ve slowly come to realize that he left a hell of a legacy for dying at the age of 24.

“When we perform, the drummers are back there, behind me, and I’m on the frontline of the stage. One night at the Beacon, I looked down and realized I was the only one left on the frontline. I guess it makes me appreciate the whole thing even more, really.

“It’s hard to stick together, and that’s probably why a lot of other good bands don’t last this long. My brother, Woody, Oakley – they can’t be replaced because they were all unique individuals. But it doesn’t mean the whole shebang has got to fold. We still have music left to play.”

Alan Paul is the author of four books, including Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined '70s as well as Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – both of which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as managing editor from 1991 to 1996. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers (with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort).