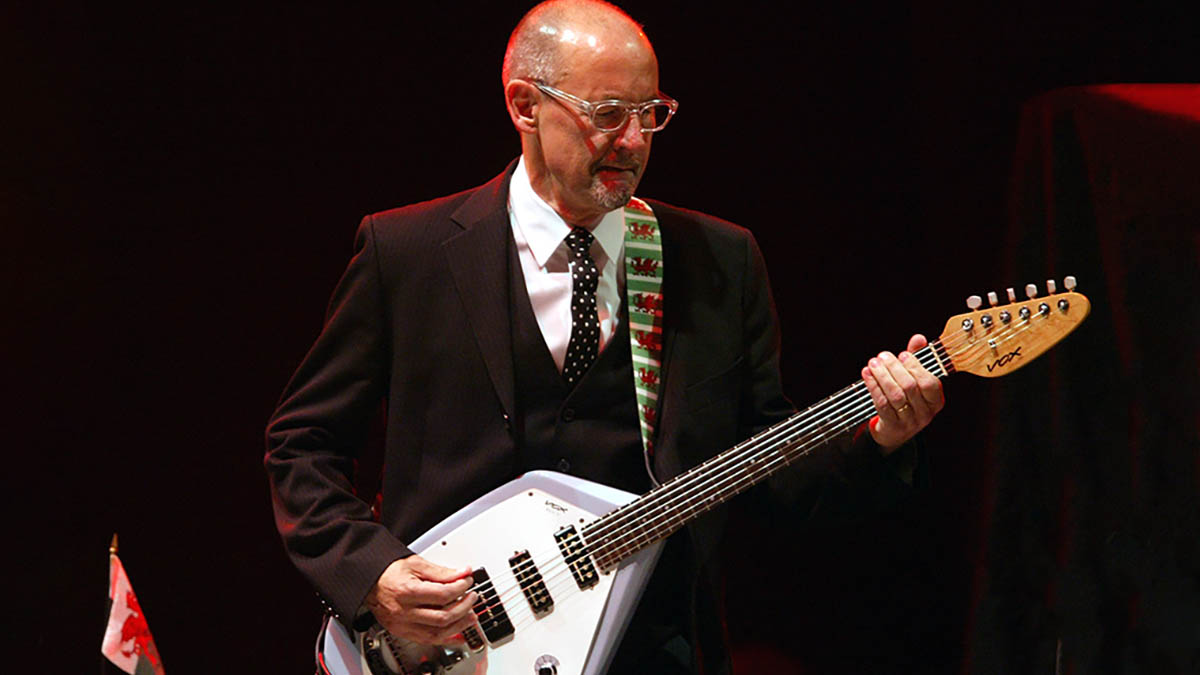

Andy Fairweather Low: “I got Fender to make me an Esquire tuned to A... a beast. I tried using that with Eric Clapton and he said, ‘Put that away! Play a proper guitar’”

Defiantly old-school in his approach to music-making, with a delightfully quirky taste in guitars to boot, everybody’s favourite sideman has a new solo album, Flang Dang

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Andy Fairweather Low first stepped into the spotlight and released a solo album 17 years ago. More accustomed to being a sideman to the likes of Roger Waters, Eric Clapton, Van Morrison and George Harrison, he’s gone on record in the past declaring that he is more comfortable in that role rather than bandleader.

Beginning his career back in the ’60s with the band Amen Corner, his solo career in the ’70s was a busy one, with albums such as Spider Jiving and La Booga Rooga achieving cult status among fans.

Now, he’s set to release Flang Dang in February of this year, although it wasn’t something that was planned.

Once again, the trials that lockdown and the pandemic brought upon the entertainment world caused Andy to take a look at the demos he had recorded at home – and an offer he couldn’t refuse from the owner of Rockfield Studios in Wales, sealed the deal and the new album was brought to life. We delve a little deeper…

What can you tell us about the run-up to your album?

“We did one live-stream gig [in lockdown] from the Hideaway club in Streatham. Then there was nothing. And it went on being nothing month after month after month. Then we got to Christmas time, and I’m speaking to Kingsley Ward, who owns Rockfield Studios. Just a social call, you know: ‘How are you coping?’

“And he said, ‘Well, what are you doing?’ I said, ‘I’m doing nothing,’ and he said, ‘You should come down to Rockfield. You can have a week for nothing. Just come down, it’d be good to see you.’ And I thought about it. It went on for a while. It got to the summer – still Covid, still in lockdown…”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Did you have a store of material ready to record?

“I make my demos at home. I’ve got a little Boss 1180 machine, a little eight-track recorder, and my recordings are badly recorded, but I love doing it. It reminds me of the old days of making records in the ’50s when it was mono and you didn’t have this kind of landscape where you could separate a bit to the left and a bit to the right – it was just one beautiful thing.

“The only thing I couldn’t stand was using a drum machine. The drum machine used to drive me crazy, but it got me to do the songs. So I thought, ‘Well, I love my demos, [but] the quality of them recording-wise, whether it’s the voice or the guitar, is not particularly good. It’d be great to get in the studio.’ So I asked Paul [Beavis], the drummer with The Low Riders, if he’d come in with me and replicate the drum patterns, and give it a bit more as well, so the perspective would be better and the quality of the sound would be better. He said yes so in we went.”

There are some lovely old-time shuffles and grooves on the record. Did any records in particular from your collection act as touchstones for the sound and vibe of this record?

“The truth is, you hear a record like Love & Happiness [Al Green] or Free with All Right Now and you start writing. However, you eventually end up with a song that has got nothing to do with All Right Now or Love And Happiness, but that’s where the fire came from.

“A friend of mine would send me DVDs every now and again, just to keep me sort of spirited and aware of what’s going on – old gospel stuff. There was one song called Calvary and it was this black preacher and his wife singing. That inspired me, that version.

“This guy singing live inspired me to have a go and make a song around that. Never quite managed to reach the heights. But the great thing about great records and great groups is if you aim that high and you fail, you’re still not doing that bad when you’re below what is absolutely fabulous.

“When I’m in my car, I’m playing Otis Redding, I’m playing T-Bone Walker, I’m playing Jimmy Reed, I’m playing John Lee Hooker or whatever it is… I’ve not moved on yet. I’m a grumpy old man and whatever’s going on today I listen to it, or watch it, and I realise that there’s no connection to me.

“The fact is the people I listened to 50 years ago are still as good. And I’m still as far away from them as I was when I first listened to them. That’s how good Ray Charles was, that’s how good T-Bone Walker, BB King, Freddie King, Albert King, Wes Montgomery were.”

What factors influenced your choice of guitars and guitar amps on the record?

“Tone’s very important to me. If you’ve not got tone, then it’s just a waste of time – it’s just rambling notes with a scratchy sort of metallic sound. No, forget it. You know, your BB Kings, your Albert Kings, your Freddie Kings… The way it was, you plugged into an amp, whatever state the valves were in, whatever state the wood and the speakers were in, you plug the lead in and that’s what it sounded like.

I want an inefficient amp and if I could just turn the volume up and that was it, I’d be perfectly happy. Let the guitar and pickup do the rest

“Until people decided, ‘Let’s get the sound a bit better.’ No, thank you. I want an inefficient amp and if I could just turn the volume up and that was it, I’d be perfectly happy. Let the guitar and pickup do the rest.

“I’ve got a Knight Arena made by Gordon and Robert Wells. I use that a lot on stage. That’s the guitar I use the most. I’ve got an Airline and it’s got one pickup on it and I love it. It’s small scale, I’ve got a 0.065 [gauge string] on the bottom and 0.016 on the top and they’re all flat‑wound. I love flat-wound strings. I do use round-wound – I’ve got a Strat with one pickup and I’ve tried playing it with flat-wounds and it doesn’t seem to work.

“What else? Well, my friend Alan Rogan who’s not with us any more but a fabulous guy, always said, ‘Andy, you need a Telecaster,’ and I’m going, ‘I don’t.’ A Telecaster is a man’s guitar, y’know? You’ve got to know what you’re doing with a Tele. But Alan spoke to Bill Nash and said, ‘You need to make Andy a Telecaster,’ and he sent it to me and that’s on the album, too.

You’ve got to know what you’re doing with a Tele

“I’ve also got a Supro with a lap-steel pickup and I got Fender to make me an Esquire tuned to A, and that is a beast of a guitar. I tried using that with Eric [Clapton] and he said, ‘Put that away! Play a proper guitar.’ Then I had a six-pickup Teisco with the bottom three strings into one amp and the top three to another – that was the Japanese idea of stereo.

“I saw Ry Cooder using one and I said, ‘I’ve got to get one of those.’ Alan Rogan was in America and he brought one back for me. I did get to use it once at the Albert Hall, but again it was, ‘What’s that? Get a proper guitar.’ ‘Yes, boss.’ And all the toys went back in the pram…”

You use some interesting effects on this latest album. The lead tone on Waiting For The Up, for example, sounds like a heavy fuzz sound…

“A [T-Rex] Quint [Machine] octave pedal. Funnily enough, when we play the song live, I let Nick [Pentelow, sax player] take the solo because it’s another pedal and I don’t want any more. I’ve got a wah-wah and an analogue delay; I’ve tried digital delays, but I don’t get on with them. I plug it in and it works. There’s no, ‘Let’s try a bit of this and a bit of that…’

“Like in the studio, I have no knowledge of what goes on in there. I’ll leave that to those that know. I get in and I play and my hope is whoever’s there just captures what I’m doing. And luckily, Joe Jones, the engineer on this album – was I lucky to meet him! A youngster. I met a youngster and he was showing me the way. How good is that?”

Stax had a sound, Muscle Shoals had a sound, and Rockfield’s got a sound. And when I went there, speaking to Joe, I said, ‘I want to hear the room.’

In terms of production values on your albums, can you explain what it is you like to hear?

“Feel is important. I need to hear the room. I can pick out Al Jackson [Stax session drummer] on any record – and I think that’s fairly unique. We’re talking about the drummer, I’m not talking about the singer or the guitar player. We’re not going, ‘That’s Freddie King…’ or ‘That’s Albert King’ or ‘That’s BB King’, you can pick out those three instantly.

“But I can pick Al Jackson out. And I can pick him out because of his kit, but I can also pick him out because of the room. Stax had a sound, Muscle Shoals had a sound, and Rockfield’s got a sound. And when I went there, speaking to Joe, I said, ‘I want to hear the room.’ When I play the record I want to go, ‘That’s Rockfield, that’s The Coach House. That’s the studio I went to in 1965, albeit not quite in the same form as it is now.’ I want to get those early Muddy Waters sounds.

“Chicago Bound by Jimmy Rogers was an album that Eric [Clapton] introduced me to. That was Muddy’s band, but with Jimmy Rogers and the sound, the room, playing together… The thing about doing that is everything has to be right. There’s no, ‘Oh, we’ll overdub that,’ there’s none of that. That’s the take.

“The strangest thing about a lot of those records is the take was the take, where all those little interactions, all those in-between licks were perfect from everybody. A bit like recording with Eric on From The Cradle.

“We’d get in at 11 o’clock and start playing whatever song it was, take a break and go back and start playing that song again, waiting for that moment when everything was right. That was a fabulous time, making that album.”

What are your plans for the record now?

“Yeah, I mean, we’ve been out playing, we just stopped now. But I’ve been on the road and I’ve been playing three or four tracks on the album. What I love is that they’re great live. These songs, certainly Dark Of The Midnight, Got Me A Party, 99 Ways, they’re now part of the catalogue and we’ll definitely be playing them live.

“My franchise is not that big, but I’m doing all right, and we’ll be back out playing in front of people. It amazes me. We go to a gig and there’s people there. I’ve had my time a few times and they’re there. They might have come in for a bit of [(If Paradise Is)] Half as Nice or they might have come in for a bit of Wide Eyed and Legless and a few others, but there’s a lot of guitar in there and there’s a lot of blues, there’s a lot of skiffle.

“I refuse to reignite the Amen Corner franchise. I get invited to be a guest on shows and they want me to be who I was, and I’m too old to be who I was. This is a period for me to be who I am.”

- Flang Dang is released on April 7 on The Last Music Company.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.