The genius of Andy Gill: paying tribute to the post-punk pioneer who influenced a generation of guitarists

The Gang of Four guitarist inspired big names from U2 and Franz Ferdinand to Tom Morello. We take a look at his diverse and storied career

“What comes next?” That was the essential question for forward-thinking rock aficionados back when the late '70s gave way to the early '80s.

Punk had blown open a big, gaping hole in the rock firmament, tearing down the clichés that had attached themselves to the music over the course of previous decades, toppling its sacred cows and even challenging the very existence of rock as a consumerist, capitalist commodity.

The time was ripe for a totally new kind of music, one born of the empowering artistic license that punk had granted all of us who had heard its clarion call. But what, exactly, might that sound like?

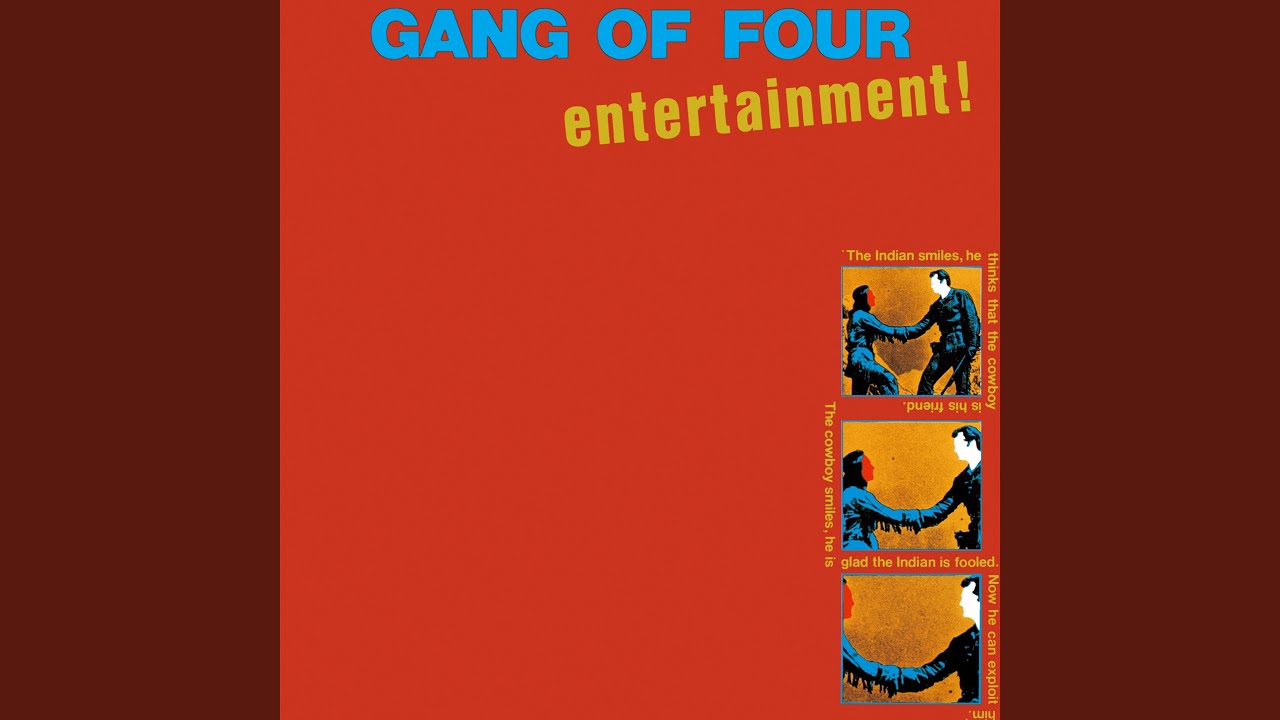

One of the most compelling answers to that key question came in the form of a 1979 album, titled, with maximum irony, Entertainment!, by a British quartet called Gang of Four. The sound was stark, bone-dry and confrontational. No big reverbs pumping anything up. No production sheen. No fake feel-good bonhomie. Just the elemental truth of guitar, bass, drums and the human voice.

Gang of Four guitarist Andy Gill, who died of pneumonia on February 1 of this year, probably would have hated to have his guitar work singled out for praise. The whole idea of Gang of Four was that every instrument was to have an equal role - “democratic music,” they called it. “Every part of it had to be radical,” Gill said in 2005. “It was building musical tension in a very precise way.”

But there’s no denying the enormous impact of Gill’s iconoclastically eclectic approach to electric guitar playing. The time demanded a style completely devoid of blues licks, power chording, showboat solo histrionics or any of the other standard tropes of rock guitar.

Gill rose to the challenge by walking a perpetual tightrope. His style was rooted in mechanistically tight, clean chording inspired in equal parts by reggae and funk. But at any moment, all that studied precision could erupt into squalling bursts of brutal feedback disrupting the music’s brooding rhythmic thrust like a terrorist bomb attack.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The only thing I could compare the Irving Plaza show to was seeing the Who for the first time in 1967, their first year in America

Alan Di Perna

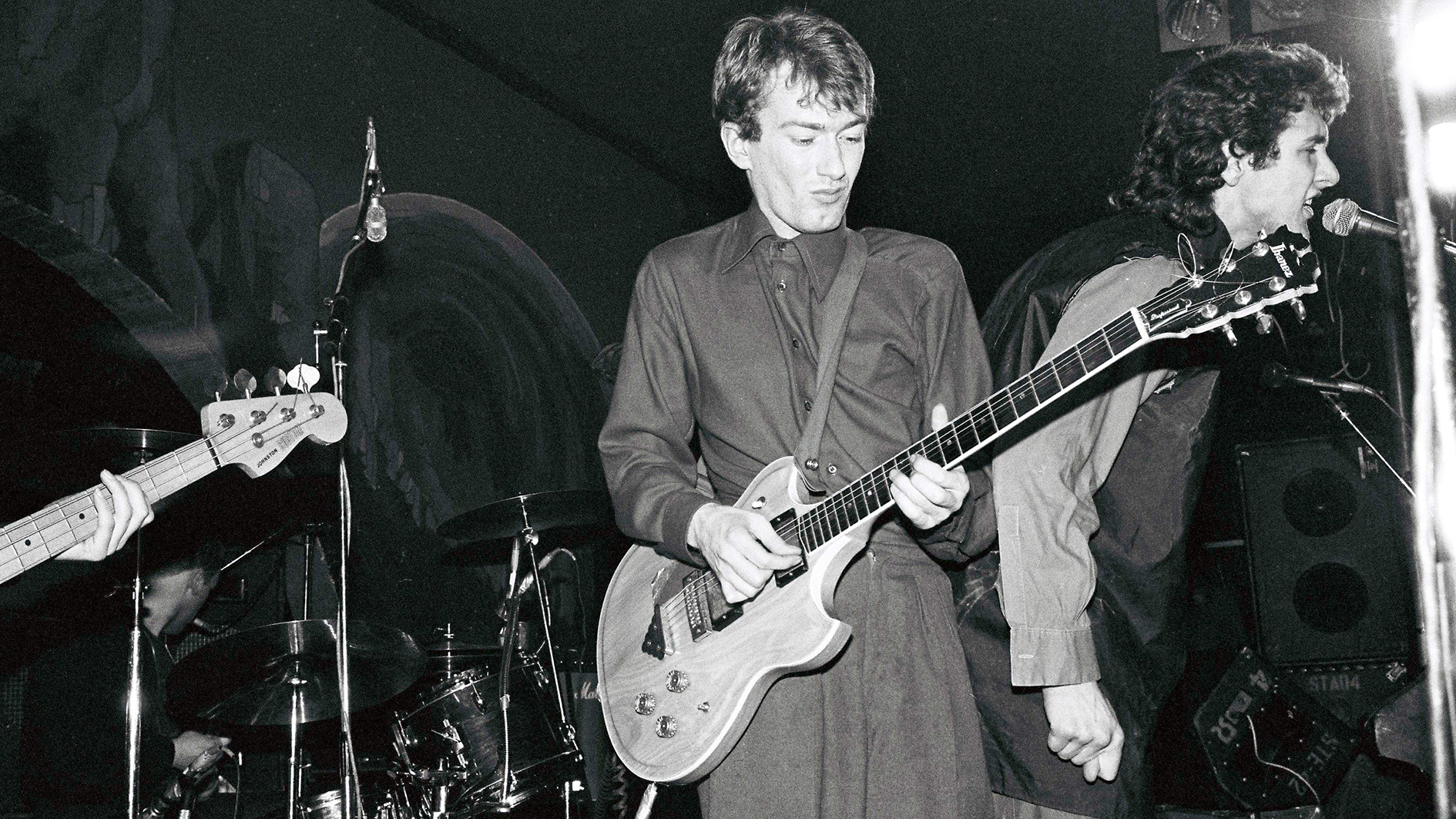

I was fortunate to witness Gang of Four in concert at Irving Plaza in New York in 1980. It was one of the most intense, harrowing rock performances I’ve ever witnessed. By the third song, Gill and his bandmates - bassist David Allen, drummer Hugo Burnham and vocalist Jon King - were completely drenched in sweat.

Gill was an imperious figure onstage, squarely at the center of the melee, yet also oddly detached, like some kind of Zen android. This latter quality Gill sometimes attributed to the influence of British pub rock guitar icon Wilko Johnson, whose machine gun rhythms also impacted Gill’s playing style.

The Irving Plaza show was unrelenting. No peaks and valleys. Just full-on frenzy, all the time, each man pounding the crap out of his instrument while King stalked the stage as if possessed. The only thing I could compare it to was seeing the Who for the first time in 1967, their first year in America.

Both performances were imbued with the kind of excitement where the whole thing feels in danger of veering totally out of control at any second. That element of danger is rock’s true essence. My ears still ringing on the subway ride home from that first Gang of Four gig, I knew I had just experienced one of those “I have seen the future of rock” epiphanies.

Nor was I alone in this. As key architects of the post-punk aesthetic, Gill and Gang of Four have influenced a broad swathe of modern rock. Michael Stipe has cited them as a key inspiration for the formation of R.E.M. Ditto for the Red Hot Chili Peppers, who chose Gill to produce their 1984 self-titled debut album.

Gang of Four exerted a considerable lateral influence on the development of hardcore acts like the Minutemen, Fugazi and Big Black. This, in turn, made them heroes for Kurt Cobain. Other acolytes include U2, Franz Ferdinand and Rage Against the Machine’s Tom Morello, whose own explosive guitar style is firmly rooted in Gill’s guerilla tactics.

His jagged plague disco raptor attack industrial funk deconstructed guitar anti-hero sonics and fierce poetic radical intellect were formative for me

Tom Morello

In a statement Morello issued shortly after Gill’s passing, he eulogized him as “one of my principal influences on the instrument, as his jagged plague disco raptor attack industrial funk deconstructed guitar anti-hero sonics and fierce poetic radical intellect were formative for me.”

Andrew James Dalrymple Gill was born January 1, 1956, in Manchester, England. While studying art at Leeds University, he founded Gang of Four with Allen, King and Burnham. The group’s name is a reference to four Chinese communist officials who fell from power right about the time Gill’s band was taking shape.

In the mid '70s, Gill and Allen used some student grant money to finance a trip to New York to check out that city’s burgeoning punk scene. Punk would provide much of the foundation for Gang of Four’s music, but they felt impelled to move beyond what had already become stylized and clichéd about punk - the down-picked guitar chug, the motorcycle jackets and tartan plaids.

To achieve this on guitar, Gill drew from a wide pool of influences. He admired Jimi Hendrix to the point of wearing a black armband when Hendrix died in 1970 - a public display of mourning. But he was also looking to sources outside of rock.

This was also a vital part of the post-punk impetus - a reaction against what was called “rockism.” Why limit yourself to a constrictive set of influences from within a proscribed, predominantly Caucasian, pool of specifically rock styles?

“With Motown,” Gill said, “the way the grooves were put together really got under my skin. And people like Steve Cropper, who is an amazing, underrated rhythm guitarist. Nile Rodgers is a descendant of Cropper in a way - someone who totally knows their chords but has got an incredible rhythmic feel.”

Reggae was the other big inspiration. “It’s the antithesis of all those rock guitarists who are throwing as many notes as possible in their solos,” Gill said. He was primarily a Fender Stratocaster player, but bucked against the “rockist” hegemony of tube amps, opting instead for solid-state Carlsbro and Peavey amplification - real proletarian gear for six strings in service of a revolution.

[Reggae's] the antithesis of all those rock guitarists who are throwing as many notes as possible in their solos

Andy Gill

Gang of Four’s debut EP, Damaged Goods, was released in 1978, the same year that saw another bellwether postpunk release, the debut album from John Lydon’s Public Image Ltd.

The following year brought the aforementioned Entertainment!, Gang of Four’s first full-length album. If they had never put out another record, Entertainment! would have been enough to establish a permanent place of honor in the annals of rock history.

As art students, Gill and Allen had studied French Deconstructionist theory. They applied this not only to Gang of Four’s minimalist instrumental approach but also their lyrical content. Powerhouse Entertainment tracks like At Home He’s a Tourist and Natural’s Not in It laid bare the futility and desperation of life in contemporary capitalist society - the stifling tedium of meaningless work, the unfulfilling vapidity of consumer culture.

The stench gets into everything, even love, which is compared to a case of anthrax in the Gang of Four’s song of that name.

Solid Gold, another heavily ironic title, appeared in 1981. It was to prove the group’s last album with Dave Allen, until a reunion that finally came along more than two decades later. An entity as combustible as the original quartet could not have lasted too long. But Gill had always had a key role in writing the group’s material, and had co-produced Entertainment!, so he was able to keep Gang of Four on track.

Allen’s replacement was Sara Lee, known at the time for her work with Robert Fripp’s League of Gentlemen and who would go on to play with the B-52s, Ani DiFranco, the Indigo Girls and Fiona Apple.

With Lee in tow, Gang of Four recorded what is perhaps their best-known track, I Love a Man in a Uniform, from 1982’s Songs of the Free. Like much Gang of Four material, it still resonates today, and in fact feels eerily prophetic.

Sadly, the original Gang of Four lineup continued to splinter. Hugo Burnham was missing in action on the band’s 1983 album, Hard. They broke up shortly after the disc’s release. But there would be several reconfigurations and one full reunion over the years. A band as important as Gang of Four doesn’t just disappear.

Gill was the guiding force in each new lineup, recording and tour. He also forged a career as a record producer, helming discs by the Stranglers, Red Hot Chili Peppers, the Jesus Lizard, Bis, Michael Hutchence, Killing Joke, the Futureheads, Therapy? and Fight Like Apes.

The final Gang of Four album of Gill’s lifetime was 2019’s Happy Now. But the band’s website indicated that another recording was in the works, stating that Gill’s “uncompromising artistic vision and commitment to the cause meant that he was still listening to mixes for the upcoming record, whilst planning the next tour from his hospital bed.”

The guitarist’s final set of Gang of Four bandmates - John Sterry, Thomas McNeice and Tobias Humble - added that “Andy’s final tour in November was the only way he was ever really going to bow out, with a Stratocaster around his neck, screaming with feedback and deafening the front row.”

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.