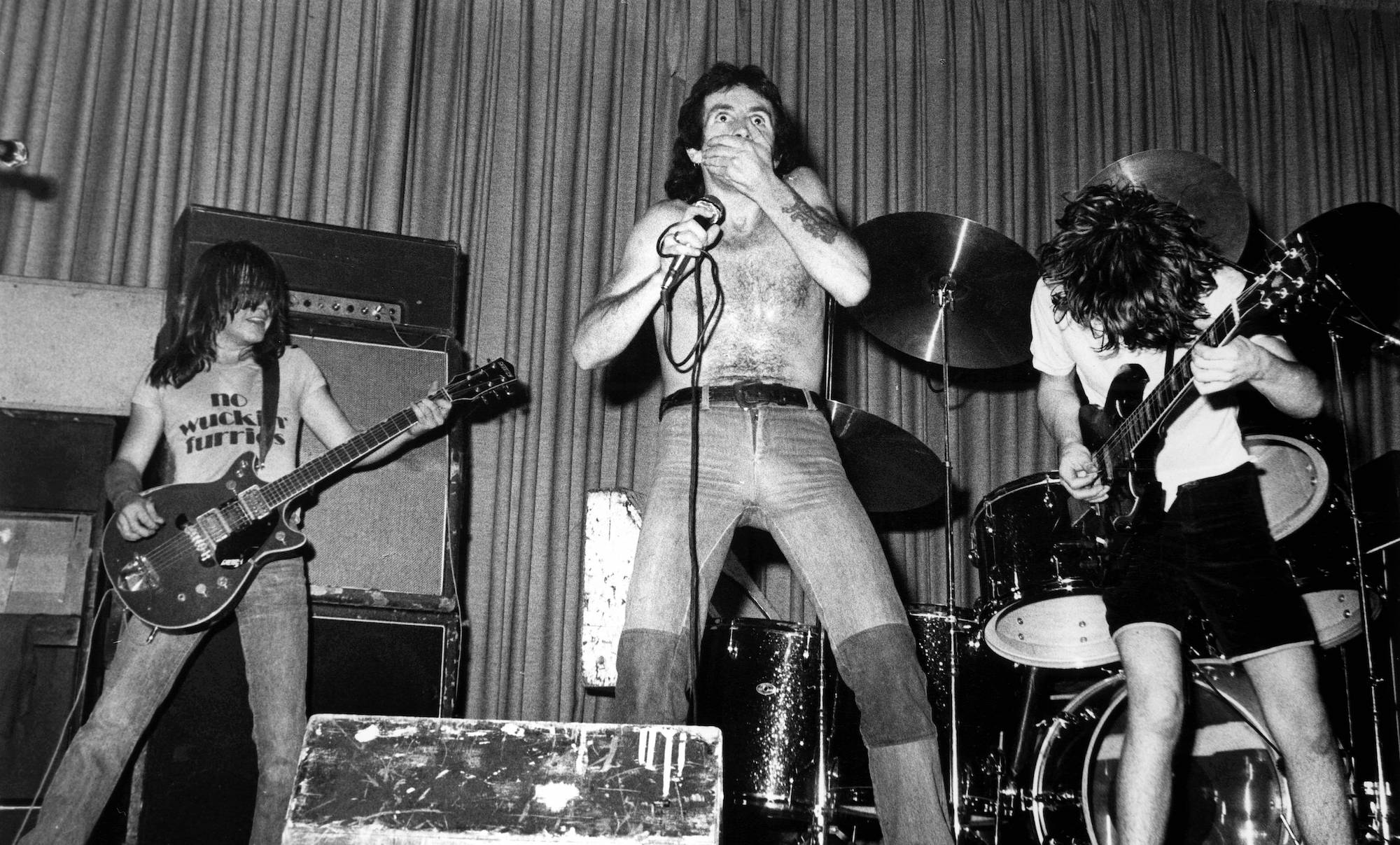

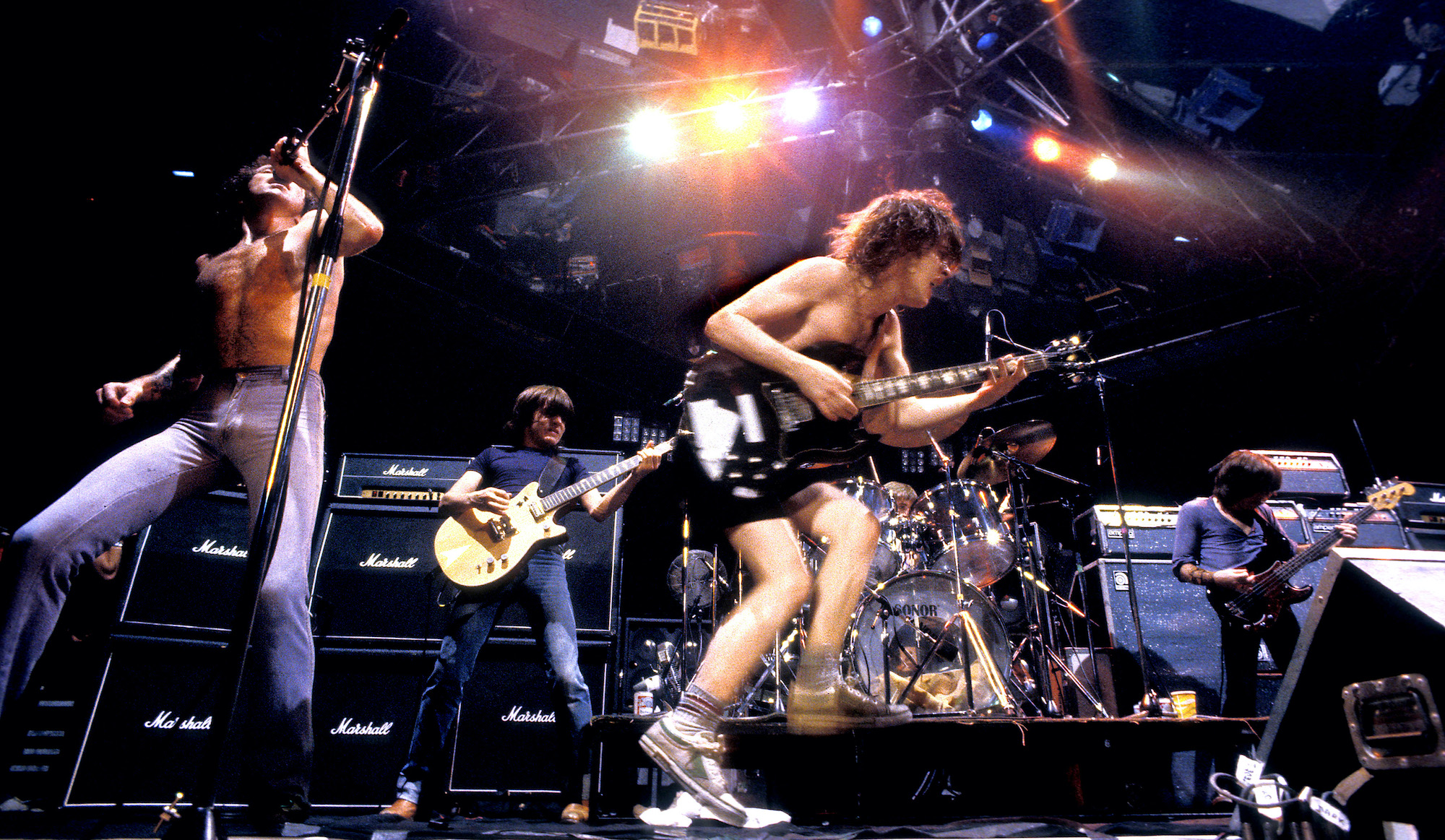

AC/DC's Angus and Malcolm Young: "Most of our early tracks speed up toward the end. After the guitar solo we’d start to take off!"

In this classic Guitar World interview from 2003, the brothers Young revisit the albums and songs that made them guitar giants

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This interview is taken from the April 2003 issue of Guitar World.

At just over five feet both AC/DC’s Angus and Malcolm Young are without a doubt two of the shortest guitarists in rock and roll history. How ironic, then, that the diminutive brothers have managed to construct some of the most gargantuan, towering riffs ever put down on tape.

Anyone who cares to argue that fact is politely invited to pop in a copy of the band’s 1980 masterpiece, Back in Black, and prepare to be summarily crushed by the title track’s mammoth three-chord whomp. And there’s plenty more where that came from.

Over the last quarter century AC/DC have unleashed a slew of hard rock anthems – such as Highway to Hell, Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap, Whole Lotta Rosie, You Shook Me All Night Long and Thunderstruck – that are firmly imbedded into the skulls of rock and rollers the world over.

Now fans will have the chance to hear those earth-shattering guitars and unshakeable grooves as they’ve never heard them before, as Epic Records, which recently signed the band to a multi-album deal, has taken it upon themselves to overhaul AC/DC’s back catalog.

So while Angus, Malcolm and the rest of the boys – singer Brian Johnson, bassist Cliff Williams and drummer Phil Rudd – get to work on their new studio effort (their final recording for Elektra), Epic is beginning its 16-album reissue campaign, which spans from High Voltage, the band’s 1976 American debut with singer Bon Scott, through 1992’s double-disc Live set.

The first batch of releases, which includes among others the seminal titles Back in Black and Highway to Hell, are currently on store shelves, with the rest to follow in the next few months. All have been remastered from the original source tapes and repackaged in deluxe Digipaks with restored artwork and rare photos.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

What’s more, each album will include a web site link where users can obtain rare and unreleased audio and video tracks from that particular era of the band’s history.

That renowned history is also being celebrated in quite a different way, with AC/DC’s 2003 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. And while fans shouldn’t hold their breath in the hopes of seeing the band take part in the Hall’s time-honored all-star jam session at the end of this year’s ceremony (“It looks like a bit of a joke when they all get up there and play over one another,” says Malcolm with a laugh. “We like to call it a catfight”), the Young brothers were more than happy to spend an Australian morning discussing the past, present and future of AC/DC.

Guitar World: Congratulations on your Hall of Fame induction.

Malcolm Young: "Abduction, more like it!"

Is it a big honor for you guys?

Angus Young: "I don’t think we’ve ever been a band that’s 'Hollywood hungry' or anything like that, where we pop up for every awards ceremony or industry show. The main thing for us has always been to acknowledge the fans that support us by buying the records and coming to the gigs."

Will you guys be wearing tuxedos?

Angus: "I haven’t even thought about it – I’ve never gone to something like this. What are you supposed to wear to these things?"

Most people don’t show up in schoolboy outfits.

Angus: "Well then, maybe I’ll go in my birthday suit!"

Unlike the majority of the artists who are inducted into the Hall, AC/DC are still recording new music. How’s work on the new album coming along?

Angus: "It’s still in the very early stages, but we’re writing away. There’s no strict timetable or release date, because with us it’s always been a case of, when we feel that we have enough good material we say, 'Okay, let’s unleash it on the public.' It’s all about quality control, you know?" [laughs]

Malcolm: "Angus and I have yet to get together and go over our stuff, but we both have a lot of music. Hopefully maybe around June we’ll start recording."

As part of your new deal with Epic, the label is remastering most of your back catalog. Atlantic Records did the same thing back in the early Nineties. What’s different about these new reissues?

Malcolm: "For one thing, the levels are up a hell of a lot louder than they were the last time. I was just comparing them the other day and the volume is twice is loud. Plus, the bottom end sounds great, and they put in a bit more mids as well. Everything sounds tight and ballsy."

Angus: "And with these new ones we involved a lot of the people who worked on the original records, as well as newer guys who have a good grasp of the recent technology. So it’s the best of both worlds. Plus, we’ve included a few little surprises and things, like some rare audio and video."

Any chance that some of the material you recorded with your first singer, Dave Evans, will turn up? Like the 1974 single version of Can I Sit Next to You Girl, for instance.

Angus: "I certainly hope not! [laughs] Because you could’ve blinked and that’s about how long he was with us. It was sort of like, when you’re just getting together as a band, he was the local guy down the road so we had him join. That lineup certainly wasn’t your dream band or anything."

Malcolm: "The guy was a schmuck, to be honest. When we kicked him out he thought we would be finished. Every time we come back to tour here in Australia, Dave seems to get himself into the newspapers by saying he was the star and he made AC/DC. So we certainly don’t want to promote him."

You can tell right off the bat when you rerecorded that song with Bon that, even though his voice was very wild and sometimes even off-key, it had such character.

Malcolm: "Bon was an original. There was another guy out of England, Alex Harvey [best known for his early Seventies work with the Sensational Alex Harvey Band], who was quite clever with his phrasing and his words, and I think Bon picked up a few things from him.

"Alex never really had a singing voice – he did more of a talking type of thing – but he would tear it up onstage. That certainly woke Bon up to the fact that there’s more to songwriting than just pop tunes."

Angus: "And with Bon, you felt his charisma. You could see him coming from a mile away. He was originally a drummer, and when he first joined up with Mal and I, he said, 'Ahh, I just want to play drums.' And we went, 'No no no. You’re singing.'"

Bon also had a real gift for penning lyrics that not only were true to the life he was leading but also managed to be funny, no matter how uncomfortable or embarrassing the situation he was singing about. Whole Lotta Rosie from Let There Be Rock comes to mind, or a track from the Australian version of that record, Crabsody in Blue.

Malcolm: "Yeah, I remember Rosie – what was it, '42-39-56'? She was quite a big girl! As for Crabsody in Blue, well, we all got the crabs at one time or another. They would spread in the car! We were touring in Australia at the time, and just about every town we went to somebody had to go into the VD clinic.

"Crabs and scabies – they were rampant at the time. Because every band was screwing the same women. That’s where The Jack [High Voltage] came from as well. Some girl at a gig accused Bon of giving her VD. She was yelling it from the front of the club. And in between songs Bon told her, 'I didn’t give you the jack. It was Phil!'

"So we wrote that song because girls tended to blame us for spreading it around. But it wasn’t our fault – it was already out there. So we figured we’d put it in a song so when these girls came to our shows we could point at ’em and shout, 'She’s got the Jack!'"

The band’s backing vocals on those early records were also great – like a street gang shouting away. Who was doing them?

Malcolm: "Mainly Cliff and me, though we used Angus on some of that stuff, like T.N.T. [High Voltage] and Dirty Deeds, because he’s got that same character in his voice. That’s what we were going for – just a bit of character. Because we’re certainly not singers!

As your producers, how big of a role did your older brother George and his partner Harry Vanda [both were former guitarists in the Easybeats, best known for their 1966 hit, Friday on My Mind] play in shaping the sound of the band?

Angus: "They were huge. Harry always had a great ear for guitar work. He could pick out things in your playing that were different from what anyone else was doing. Which was particularly great for me because I was the youngest, and when I would get in the studio and pick up my guitar I would tend to just go wild right off the bat. Just blast out every note, you know? [laughs] And Harry and George would politely ask, 'That’s great, but can you do something that’s a little more in there with the track?'"

Malcolm: "They would say, 'Just come into the studio and do what you do onstage. We want to capture that live excitement.' That’s why you’ll probably notice that most of our early tracks speed up toward the end. After the guitar solo we’d start to take off!"

And George even pulled double duty on High Voltage, handling all of the bass parts.

Angus: "Sure. He used to fill in a lot in those early days. At that time the band was all about getting the best guys you could find to play the music. It wasn’t always easy to find people who had the right chemistry and who dug playing our type of music."

Did you guys have a clear vision right from the beginning of what you wanted AC/DC to sound like?

Angus: "I suppose it was more of Mal’s thing. When I first got together with him I said, 'Well, what are we going to play?' And he said, 'That’s obvious – what’s missing out there?' And I, of course, replied, 'I don’t know. What?' I was as baffled as anyone! And he said, 'A good hard rock and roll band.' Because it just seemed to be a dead time, judging from what you’d hear on the local radio here in Australia and also what was coming from your shores and out of Europe.

"Sure, you had the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin, but there was very little good, solid rock that appealed to the youth of that time. And we noticed it straight away when we first started playing about. People were showing up in droves just from word of mouth."

Other than Highway to Hell, you recorded all of your Seventies-era albums at Albert's Studio in Sydney. What was that place like?

Malcolm: "It was great – the best studio we’ve ever recorded in. But they changed it around the time we were doing Powerage. They built a second, bigger room that was geared up with all the latest equipment of the day, like the solid-state SSL desks. But we preferred the old Neve boards, the analog ones that had that warm, valve-y sound. So we ended up going back into the little room. In fact, all the records we did at Alberts were recorded in that small room."

Would you record together as a band?

Angus: "Sure. We’d all get in there and start off with the rhythm tracks. Sometimes, we’d do it all. George would say, 'Go ahead and just play the guitar solo.'"

While you were doing the basic rhythms?

Angus: "Yup. And also any little fills that were in the song. Because it would add to the atmosphere. High Voltage was one of those tracks. It was the first take we’d done, and every take after that just seemed shallow in comparison. So that was a first-timer, guitar solo and everything. And it was great for me, because then George would go, 'All right, you’re done!'" [laughs]

Would you ever go back and overdub rhythm tracks?

Malcolm: "Only if it was really necessary. Occasionally we might go out of tune because were recording some pretty fiery stuff and we’d be hitting the guitars pretty hard. So sometimes we’d have to drop in and fix it up. But we’d do as little as possible."

What amps were you using on those early records?

Malcolm: "The same stuff we were playing onstage. We would just send the gear over to the studio after a show, set up and crank it out until six or seven in the morning. Then the next day we’d go off and do another gig. So the equipment was going in and out all the time.

"In the very early days I was using one of those Marshalls with the small logo on the front. Starting with Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap in ’76 I began using a modified Marshall bass head. That gave me a much bigger and cleaner sound. And I’ve used it on every album since."

Angus: "For me it was always Marshall 100-watt Super Leads. I had bought one secondhand somewhere in Australia when I was younger, and it had a great sound. Very bright. And that was it. Back in those days there wasn’t a lot of money for us to go looking around for gear. We didn’t start off as millionaires, though I wish we did!"

Malcolm, were you always using your ’63 Gretsch Jet Firebird? [Severely modified, Malcolm’s original Gretsch has two holes in the body; one in the center, a result of first installing and then removing a humbucker from between the Firebird’s two Gretsch FilterTron pickups, and one below the neck from when he subsequently removed the original neck pickup, leaving just one FilterTron in the bridge position. In addition, all of the controls have been disabled except for the volume knob on the horn of the guitar]

Malcolm: "Yes. I think the only time I didn’t was when we recorded High Voltage. My guitar had been broken, and we had to get the song down that night, so I just grabbed whatever was lying around the studio. I believe it was a Gibson L-5. To this day I still hear that track and go, 'Ugh.' [laughs] But other than that it’s the Gretsch on everything."

And for Angus, of course, it was always the Gibson SG.

Angus: "Right from the very beginning."

Is there any AC/DC song where you’re playing something else?

Angus: "Actually, come to think of it there is one track – Live Wire [High Voltage] – that I did with another guitar because I had broken mine as well. I did an overdub with a Les Paul, I think."

So on Live Wire we can hear Angus Young playing a Les Paul?

Angus: "Sorry, but that would be no. Once my SG was fixed I just went out and recut it!"

What year is that first SG from?

Angus: "I think it was a ’69 or a ’70, although I had someone else tell me it might even be a ’71 or ’72. So I don’t really know for sure. But I still have it. I use it in the studio."

How about onstage?

Angus: "Occasionally, but I get a bit queasy sometimes because I know how I play. In the early days that guitar would get broken in two, or I’d bang the headstock off.

"Nowadays I do my best to look after it. And Gibson did a good copy recently for me. They have all these new tools – 3D scanners and whatnot – that they use to help them replicate guitars. So they took mine in, X-rayed it, put it on a drip, whatever they do!" [laughs]

How many SGs are currently in your collection?

Angus: "It must be in the hundreds. I lost count years ago. I remember when I first went to America I bought some on that street in New York…"

48th Street?

Angus: "Yeah. There used to be a little shop on the corner there where I bought a couple of SGs. And one of them was great. The guy who sold it to me told me there was a '2' on the back of it, and apparently that’s what they put on the rejects. So I said, 'Yup, that’s me!' I used that guitar on Highway to Hell."

Highway to Hell was the first AC/DC record not produced by Vanda and Young. Why did you decide to work with someone new?

Malcolm: "Basically, Atlantic, our record label in America, said, 'We’re gonna drop you guys unless you get another producer.' We were selling a couple hundred thousand copies every time out, but they wanted bigger and better."

Angus: "Also, George and Harry figured it was a good time for us to go out in the world and try something new. Because George always used to say, 'You never know, somebody out there might have something different to offer you guys.' I suppose it was a bit like how birds do it – you get kicked out and have to learn to fly on your own."

Most people tend to think of the second phase of your career beginning with Brian Johnson coming in on vocals and recording Back in Black. But it seems more accurate to say that the turning point was really Highway to Hell, when you started working with Robert John “Mutt” Lange.

Angus: "I would agree. For the band, and especially myself and Malcolm, George had guided us since we were young. When we were kids he’d get a big kick out of taking us down to the recording studio and showing us what was going on. He knew it was such a big deal for us to go into a studio and see how everything worked, and to see people playing guitars. So it was strange to be going into a studio without him."

Was there trepidation about working with Mutt, who at that time wasn’t known for producing hard rock bands?

Angus: "Sure. We were very cagey about working with anyone new. At one point we thought, Is there someone out there, other than George and Harry, who can really do justice to our music? And in fact, some of the things we’d hear about what people were doing with records, we’d be like, 'Geez, that’s too extravagant.'

"You’d hear about producers taking a band away for two years, putting ’em in some mansion. And that was something we didn’t want. So we were pretty nervous."

At one point your record label wanted to pair you with Eddie Kramer.

Malcolm: "The label offered us Eddie, saying, 'He engineered for Hendrix.' But he didn’t really fit in with us as a producer. We showed him the riffs for Highway to Hell and he didn’t quite get it. We thought, This guy’s out of touch with what we are."

Angus: "And at the same time, I suppose any ideas that Eddie had didn’t seem to inspire us. I don’t know why, but he kept talking about pianos. Maybe he thought that a piano was an interesting thing for a rock and roll band. But that was the wrong word to use around us. Too classical sounding! But as I said, there were some very extravagant things going on at that time."

Mutt is one person in particular who is known for making extravagant records.

Angus: "Before we started working together, Malcolm called him up and more or less said, 'Well, what can you do for us?' And Mutt had the right answers. He went, 'I don’t think you need to be in the studio for a long time.'

"We had already written most of the tracks for Highway to Hell, so Mutt said he’d just give it a bit of spit and polish and we’d be out in five or six weeks. And we wound up going ahead of even that. We went in and did all the backing tracks in about 13 days or something. In fact, I think that was probably the quickest album we did with him.

Did he change your approach at all?

Malcolm: "We still laid the tracks down live, because that’s what we’re about. And because Mutt realized that we were a good band who could play their instruments he just let us go for it. The freedom was there. And we gave him freedom as well – we would try anything he asked of us.

"Mutt fit in really well with the band. It was a shame we never got back together with him after For Those About to Rock. Actually, we saw him recently at a gig in Paris and afterward he said, 'You’re still the best fucking band I ever worked for!' So that’s a nice compliment. Maybe one day we’ll work together again."

After Highway to Hell your sound got considerably darker and heavier. Was that a result of Bon’s passing, or was the band naturally heading in that direction anyway?

Angus: "With Back in Black that’s just where it was going. Some stuff, like Hells Bells, was obviously written with Bon in mind, but then a lot of it was written when Bon was still around.

"I remember during the Highway to Hell tour Malcolm came in one day and played me a couple of ideas he had knocked down on cassette, and one of them was the main riff for Back in Black. And he said, 'Look, it’s been bugging me, this track. What do you think?' He was going to wipe it out and reuse the tape, because cassettes were sort of a hard item for us to come by sometimes! I said, 'Don’t trash it. If you don’t want it I’ll have it.'

Was the little single note lick his, too?

Angus: "Oh yeah. In fact, I was never able to do it exactly the way he had it on that tape. To my ears I still don’t play the thing right!"

Probably one of the biggest misconceptions surrounding the band is that there are demos of Bon singing Back in Black songs.

Angus: "He never sang. He was actually supposed to come in that same week he died. He had this pile of lyrics he’d been kicking about and he said, 'Well, maybe I could come in and try out some ideas.' A week earlier, however, Bon did come down to the rehearsal room and play some drums.

"Malcolm and I were working on Have a Drink on Me, and Mal had been on the drum kit and wanted to play some guitar. So Bon walks in and Mal goes, 'Just the man I wanted to see!' Since Bon had been a drummer we had him hop behind the kit and we demoed the track."

What gear were you using on Back in Black?

Angus: "Still 100-watt Super Leads. The old-style ones, without those preamp things. I remember at the time that was the new thing Marshall was trying to push. They were trying to get people interested in ’em, but I wasn’t really interested."

Malcolm: "In addition to the Super Leads I think Angus went to a smaller 50-watt Marshall for his solos. Just for some extra warmth. I was still using my Marshall bass head, and I believe Cliff had a little SVT amp."

Some of the solos on that album are so memorable, particularly on You Shook Me All Night Long and the title track. Were they worked out beforehand?

Angus: "Some were totally off the top, and there were some that I took a bit longer with. With Mutt, he’d just listen and tell you when he thought something was great. Sometimes I’d be there for a whole day doing one guitar solo, and then he’d go, 'Remember what you were playing at the beginning?' [laughs] And I’d have to go all the way back to the start.

Malcolm, have you done any solos over the years?

Malcolm: "A few, but to be honest I really don’t know why! On the Australian version of High Voltage there was a song called Soul Stripper where me and Angus traded off on some licks, and there’s also another tune on there, You Ain’t Got a Hold on Me, where I did a bit of soloing. But when we got onstage it was just obvious that I should sit in the back and keep time, because Angus, as soon as he put on that school uniform, he started going all over the place.

"It evolved very naturally. And I loved it because I always enjoyed the rhythm side, just keeping it tight and getting the groove going. When that’s on the money there’s no better feeling."

Since its release, Back in Black has sold more than 40 million copies worldwide. Why do you think that album in particular connected with so many people?

Angus: "It’s probably all of the elements combined. At the time I suppose there was a lot of curiosity. The fans were buying it because they were eager to see how it would be different from what they knew. And then the songs themselves were special.

"When we were in the studio we were thinking it could be our last record, so that was a big push. When you lose somebody like Bon, who’s a very upfront guy, he was the identity of the band for a lot of people. We didn’t know if we could get past that. We knew we had good songs, but even so, you can have great songs and at the end of the day people can still go, 'Yeah, whatever.'"

And over the years those songs have appealed to a much wider audience than just your typical rock fans. Have you, for instance, had a chance to hear Celine Dion’s version of You Shook Me All Night Long?

Malcolm: "Somebody sent me a video of that. I was impressed – not necessarily with the vocals, but with the fact that she was able to do Angus’ duckwalk with the fucking shoes she had on! I thought, Fucking hell, she’s got some balls to do that!"

For 1983’s Flick of the Switch and ’85’s Fly on the Wall the two of you decided to handle production chores on your own. Why?

Angus: "We were probably looking to go back in a way. We had worked with Mutt for three records in a row and we felt that we knew what we wanted and how to get it. So we decided to have a go ourselves.

Malcolm: "We said, 'Forget all this big production shit, let’s just go back to the bare bones.' And that was what Flick of the Switch was – a really raw, basic record. It was a slap in the face to everything that was going at that time. We decided to knock out 10 tracks and put it out there.

"Even the album cover was very stripped down. And for the Flick of the Switch video, we set up in a big hangar and told the crew, 'We’ll be playing – you film. Walk around the band, do whatever the fuck you want. We just want it done today.' Neither of those albums were big sellers, but we were just trying to become a simple little band again, because it was getting pretty complicated carrying cannons and bells everywhere! So that was a bit of an interesting period."

You came back strong in 1990 with The Razors Edge, which was probably your biggest record since Back in Black.

Malcolm: "When Angus came up with Thunderstruck I thought, Fuck, we’ve got a great track here. And that set the standard for that album. Also, during the tour before that [for the Blow Up Your Video record], my drinking had gotten really out of hand. So I decided to take a little breather from the band, and that gave me a bit more time there to mess around with ideas.

"I started using some keyboards, just sampling the guitar into it for the sake of trying something different. It was interesting, but after that album I decided I was done with keyboards. Couldn’t be bothered anymore with that shit!"

You worked with Bruce Fairbairn on that record and have since worked with Rick Rubin, another well-respected producer. In the end, though, you always return to your brother George.

Malcolm: "When we worked with Rick, there was something not quite right there. He’s not a real rock and roller, that’s for sure. All he worried about was the snare drum. We would never go back to him. We thought he was a phony, to be honest! But George and Harry are real rock and rollers. They don’t care if an album doesn’t sell. They just want to record good music."

Angus: "I think every now and then you need that vitamin boost, you know? And George is great because he has a lot of experience. And also, he knows what’s out there, even by today’s standards. He grasps new things instantly. He always manages to pull something new out of you, and I love that about him."

Will he be producing this next record?

Angus: "I don’t know. We had to really twist his arm to do Stiff Upper Lip. Because the poor guy has spent most of his life in studios. But he said, 'For anyone else, no, but for you two guys, yes.'"

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.