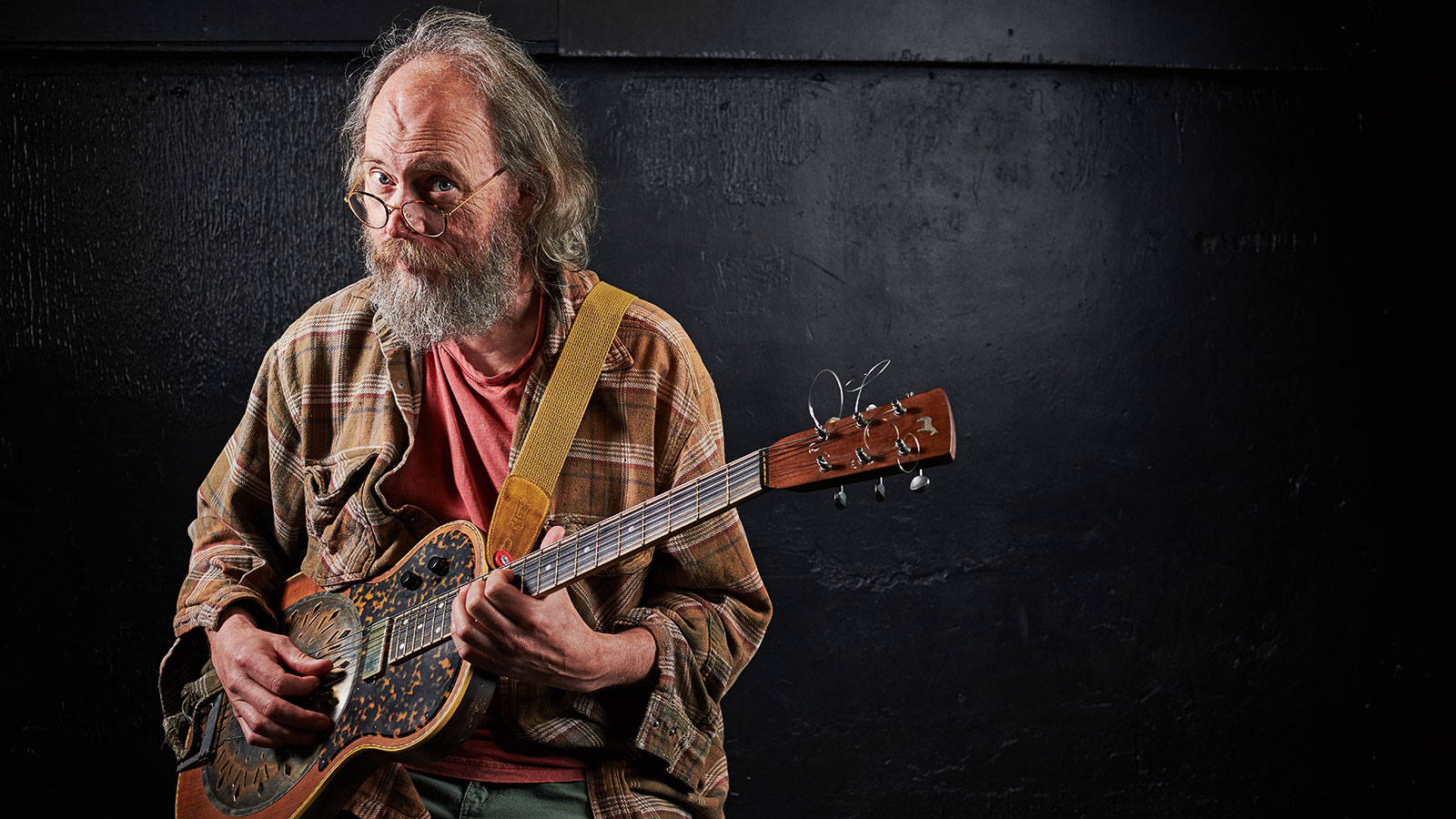

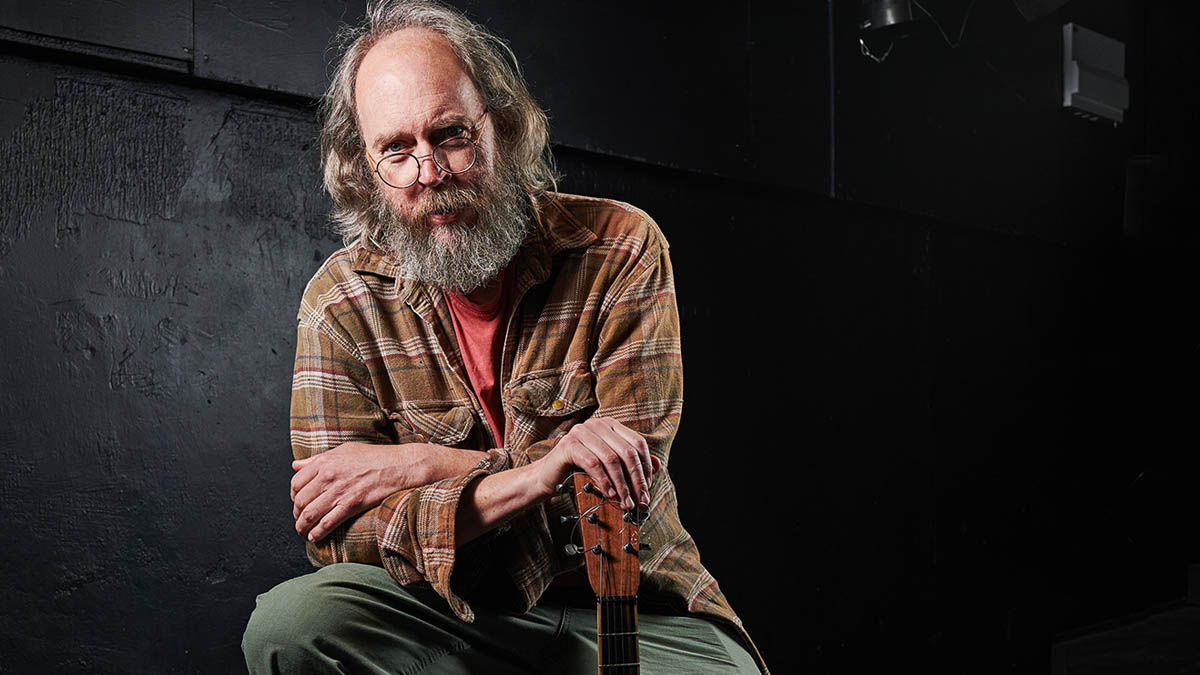

Charlie Parr: “If I get to touch the strings and play a little lick and make some sounds, everything else is gravy”

The Minnesota blues legend joins us, with a beautiful Mule Resophonic guitar in hand, and explains why playing guitar is something he does without fail every day

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It’s before soundcheck in a cool (in both senses) cellar at Bristol’s Exchange venue and prolific blues stalwart Charlie Parr is part way through a UK tour, his first since the pandemic.

We immediately get to talking about tour exhaustion and finding the time to play guitar, something Charlie has managed to remain consistent with for decades.

“Yeah, playing guitar is something I do every day, no matter what,” he says, firmly. “The nice thing about lockdown was that I got to practice – because when you’re touring you never get to do the kind of practice that you do at home. Soundchecking and performing are definitely not practicing; your focus is on something different and the rest of the day is spent traveling, so you can’t play.”

Charlie’s dedication to his instrument is clear, which must have made the time after breaking his shoulder in 2018 particularly difficult.

“I destroyed my shoulder falling off a skateboard,” he grins. “When I was 15, I was made out of rubber, but this time I could hear everything in there just [crunching sound]. It was gone! The morning after the accident I realized it would be the first day in decades that I hadn’t played a guitar. Every day I would play – even if I was really busy, I would poke at it a little bit – so it felt devastating.”

He pauses a moment. “There’s this part in [1973 novel] Breakfast Of Champions by Kurt Vonnegut where he’s talking about a painter who says that nothing matters except putting paint on canvas.

“All of the selling and crap doesn’t matter – you could put them in a space capsule with a canvas and paints and they’d be happy. I feel that way about guitar playing. If I get to touch the strings and play a little lick and make some sounds, that’s all I’m after. Everything else is gravy.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But there’s plenty of gravy, too. Charlie has put out 16 studio albums, plus compilations and collaborations. His most recent release, last year’s Last Of The Better Days Ahead, is a beauty, deliberate in pace and sparse in arrangement, with a reflective nature that is in keeping with many people’s moods after the past couple of years.

“This record was all written in the first months after the lockdown began,” Charlie tells us. “But it was always going to be a more inward- looking album and I think my writing has been leaning that way for a little while. It’s because I’m feeling aging hard...

“I don’t remember in my 30s and 40s thinking, ‘I’m 35 years old,’ but now I do that! Or I wonder, ‘How old’s that guy?’ I don’t wanna do that! I want to get back to where it’s not important, but I’m preoccupied – and when I began writing, those preoccupations came right out into the record.”

Though this may sound rather melancholy, there is a lot of beauty on the album, particularly on standout songs such as Everyday Opus and the 15-minute instrumental Decoration Day.

“I’m glad you like that one,” Charlie smiles. “That was my favorite, too. I was surprised by it because the whole record besides Decoration Day was done in one studio in one afternoon and, except for one song, in a single take. But Decoration Day was done in two parts in a larger studio, where I had my 12-string and my friend Liz [Draper]was on upright bass.

“We improvised the first half of the song and then switched to electric instruments and brought in the drummer and keyboard player. Then we listened to the first half and reacted to it. So that setup makes up the last seven or eight minutes of the song, but it’s all improvised.”

Changing Pace

This sense of improvisation runs through the record more than on Charlie’s previous releases and gives much of the sound a meditative quality.

“Well, this last year a lot of the music I’ve been listening to has been this kind of ambient, experimental stuff that has a lot of improvisation involved,” Charlie says. “I really wanted to bring that into my songwriting. I have this side project called Portal iii [with Liz Draper on bass and Chris Gray on drums], which is a completely improvised electric drone band and I play electric guitar.

“That music has been beyond cathartic and is deeply important to me. I wanted to bring some of that vibe into my songwriting, so a lot of the songs, especially Everyday Opus and Rain, have the bed of music existing in that ambient world.”

I’ve learned a lot from guitar players like Marisa Anderson about pacing and rhythm and tempo

Perhaps as much as this aerial improvised nature, the ghosts of players including John Fahey and particularly Robbie Basho appear throughout the album, the latter being a master of the spiritual and ambient side of acoustic guitar playing.

“I love both of those guys so much and I was very obsessed with Fahey for some time, but I’ve slowly become more of an appreciator of Basho in the last few years,” Charlie says, which seems fair as Basho certainly holds more challenges for the listener than Fahey. “Yeah, you have to come to him because he’s not really coming to you. I’m a big fan now of Basho and also of more contemporary players like Chuck Johnson and Marisa Anderson,” he continues.

“She’s just great, and the depth and tempo she manages to achieve, especially on her Cloud Corner album, is just amazing. I’ve learned a lot from guitar players like Marisa about pacing and rhythm and tempo. When I was starting out, I was really into guitar players like Mississippi Fred McDowell, whose pacing was more aggressive.

“I really liked playing that way for a long time. But then suddenly didn’t [laughs]. I can still get there, but – I don’t know if it’s a product of me getting older – I just get tired faster and want to stop and walk for a while. It’s become more important to me to think about that.”

Get Behind The Mule

With this resonator guitar, there’s a richer variety of sounds. There’s a whole bunch of stuff there that I appreciate more now than I did before

At this point, Charlie turns to the gorgeous resophonic guitar in its case at his side. “I also like that pace when I’m playing because I can explore dynamics,” he says.

“When you’re going flat out, there’s no time to think about how the strings are behaving because you’re always cutting them off. With this resonator guitar [pictured above], there’s a guitar and an amplifier and there’s a richer variety of sounds, so when it’s ringing and I’m not touching it, there’s a whole bunch of stuff there that I appreciate more now than I did before.”

The guitar is beautifully built, with a wonderful acoustic tone and a fast, satisfying neck.

“It’s made by Mule, which is a resophonic company, and it’s called a Mavis,” Charlie tells us. “It looks like a solidbody Les Paul type, without a cutaway, but it’s got a soundwell and a single cone resonator in it and a pickup that Ted Vig made.

I like that darker tone – you know on a Jazzmaster when you flip up to the rhythm channel and everything gets dark?

“I wanted kind of a jazz-sounding pickup and he made me a low-output unpotted mini-humbucker. It’s really nice and blends with the natural sound of the guitar really well. I’m putting it through a ’68 Princeton reissue that Fender makes. It’s nice and pretty clean because it doesn’t have a master volume.

“I’m also using a parametric EQ from Tech 21 called the Q\Strip,” he continues, “which gives me opportunities to shape the tone a bit more. I like that darker tone – you know on a Jazzmaster when you flip up to the rhythm channel and everything gets dark? You’re still getting the treble sounds and the whole spectrum, but everything just sounds darker. I like that a lot and this guitar can get to those dark spaces really quickly.”

- Last of the Better Days Ahead is out now on Smithsonian Folkways.

Glenn Kimpton is a freelance writer based in the west of England. His interest in English folk music came through players like Chris Wood and Martin Carthy, who also steered him towards alternate guitar tunings. From there, the solo acoustic instrumental genre, sometimes called American Primitive, became more important, with guitarists like Jack Rose, Glenn Jones and Robbie Basho eventually giving way to more contemporary players like William Tyler and Nick Jonah Davis. Most recently, Glenn has focused on a more improvised and experimental side to solo acoustic playing, both through his writing and his own music, with players like Bill Orcutt and Tashi Dorji being particularly significant.