“Music is such therapy for me. When I’m writing a song I’ll say something I didn’t know I was bothered about”: For Darius Rucker, the industry has brought joy and cut him to the bone. Now he’s written a book on living with his mental health challenges

The Hootie & the Blowfish frontman hopes his memoir will help others out of the depression and anxiety traps that led him into substance abuse

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This article is part of Guitar World's series of interviews and features with artists addressing and raising awareness around themes of mental health, particularly as they relate to musicians.

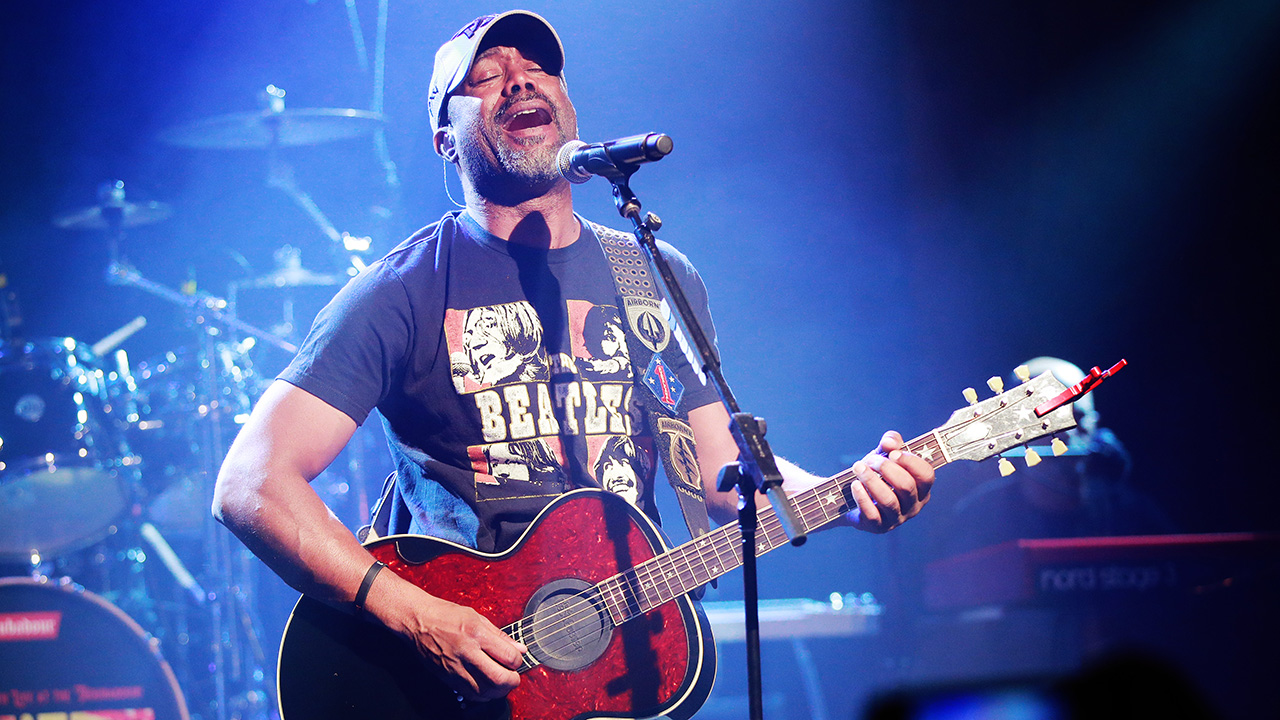

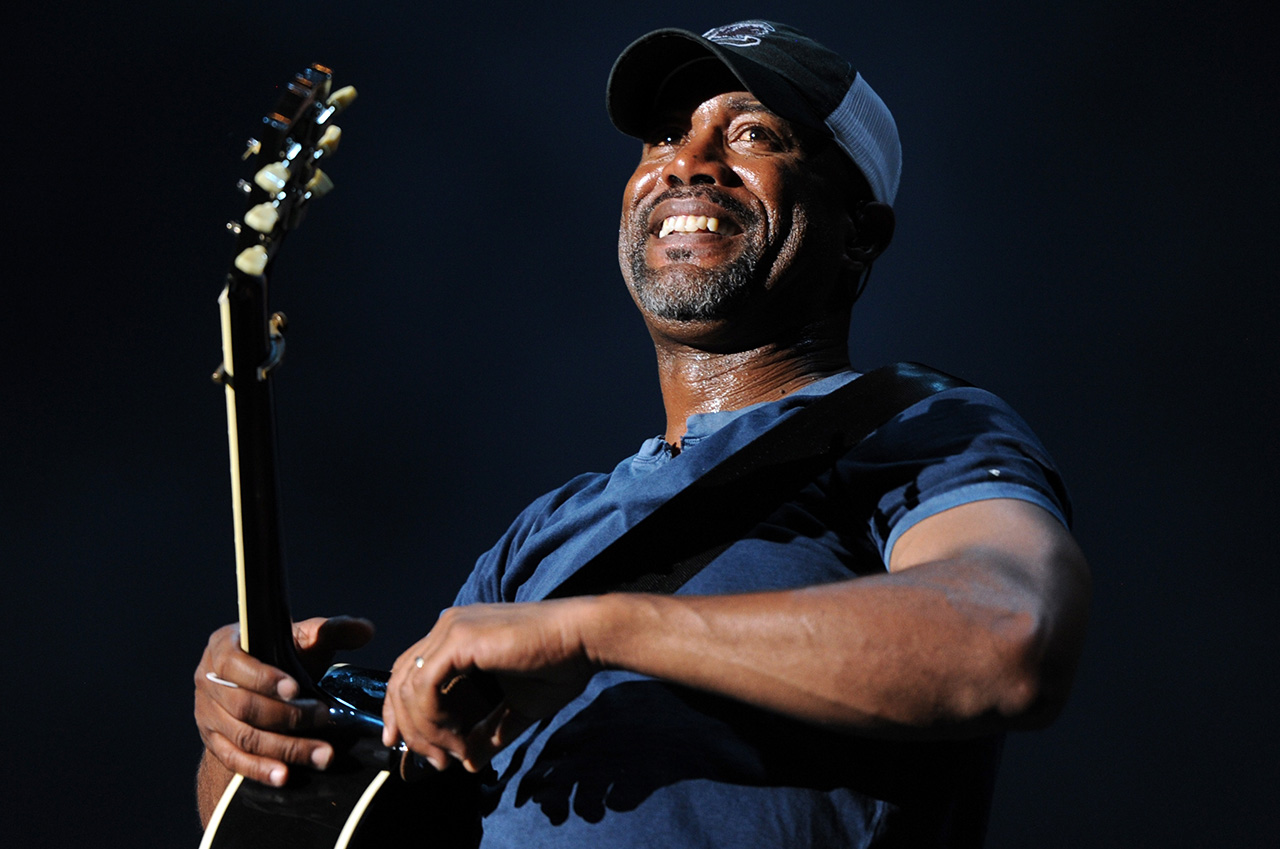

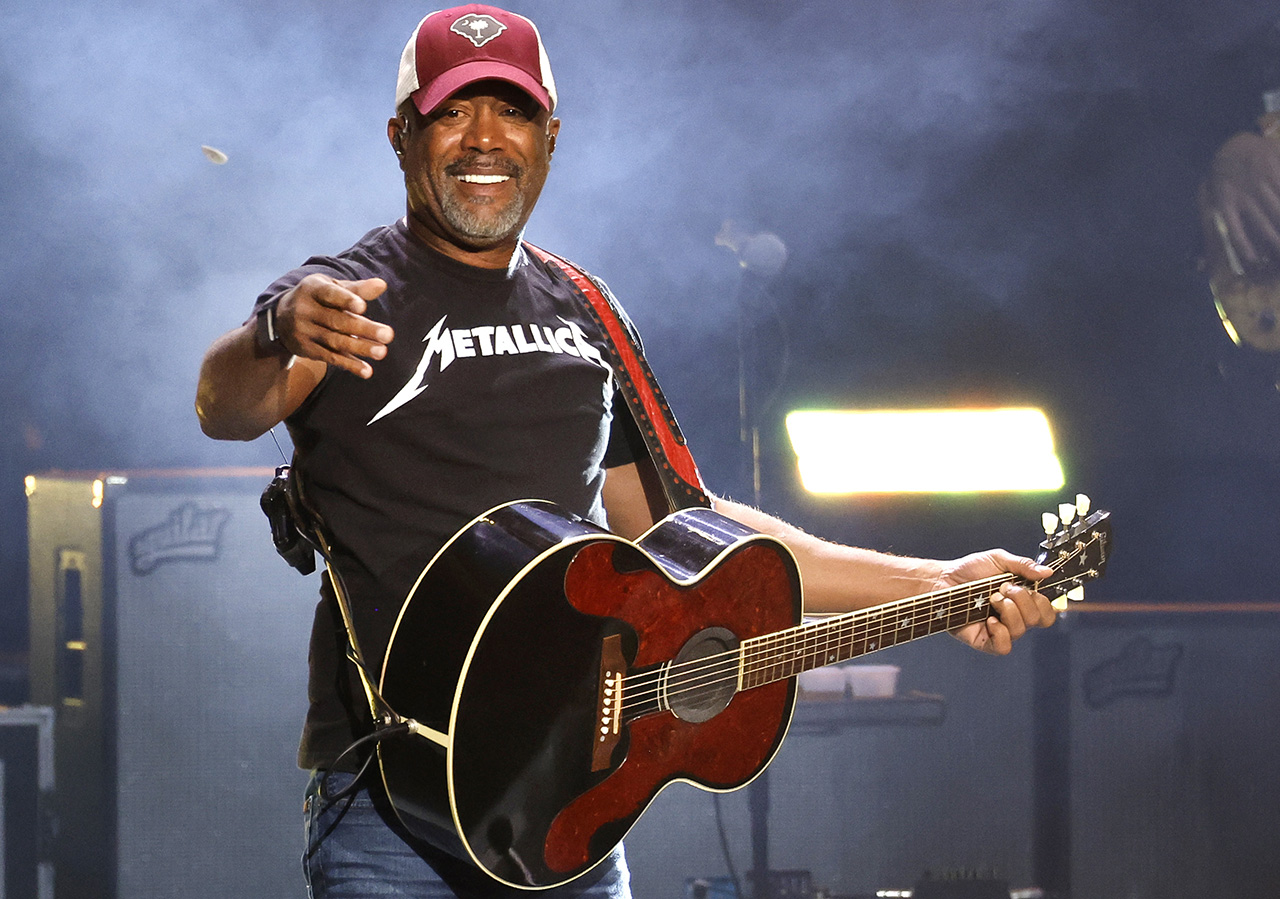

Before three Grammy Awards, a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, multi-platinum albums as lead singer and rhythm guitarist for Hootie & the Blowfish, four No. 1 country albums and 10 No. 1 country radio singles on his own, Darius Rucker was simply “Carolyn’s boy,” a self-described “little kid from South Carolina that just wanted to sing.”

Decades later, with Carolyn’s Boy as the title of his 2023 album, and his autobiography, Life’s Too Short: A Memoir, available now, Rucker describes himself the same way: “I'm still that little kid from South Carolina that just wants to sing.”

He’ll be doing that again in front of audiences beginning May 30, when Hootie & the Blowfish launch their first full tour since 2019. To date, the band’s album sales total over 25 million, with their 1994 debut, Cracked Rear View – 21 times platinum – among the top ten best-selling albums of all time.

If you’re looking for The Dirt: Darius’s Version, Life’s Too Short is not for you. The heart of the book is his lifelong passion for music. The details are there; nothing is hidden, including family struggles, band strife, his substance abuse, experiences with overt and systemic racism in and out of the music industry, and his personal battles with mental health.

The difference, however, is that he describes everything with finesse – at times referencing individuals by using a single initial, rather than calling them out by name.

Rucker has experienced tremendous peaks and cavernous valleys over the course of an enviably successful career. Throughout, he remains guided by faith and empowered by music.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

On Sunday Sitdown you were discussing Carolyn’s Boy, and you said you had “a bad mental health day” in the studio. What did that mean?

“I think at that moment I was a little depressed. I was in a funk and couldn’t get happy. I was stressed about too many things – a lot of things I had no reason to be stressed about – and my mental health wasn’t what it should be when I’m in a studio working. It was one of those days where I needed to talk to somebody, or I needed something to get me out of that funk.”

What’s your earliest memory of bad mental health days?

“In high school you start to realize you might have had it as a kid, but you didn’t think much of it. It was just a bad day, and then somebody snapped you out of that place by saying, 'Let's go to the park,' or something.

“In high school, there were days that I got down; but especially in the ‘80s there was nobody to talk to or talk about it. So you’d try to go on, fight through it – until you're having worse and worse days. It took becoming an adult and realizing there’s help out there before I really got a grasp on how bad a bad mental health day can be.”

When did you begin addressing it?

“I started dealing with it privately at the turn of the century, when I got my first therapist and really talked about it and realized how much that helps. Even when things are not that bad, it can feel bad for you with mental health.

“When I started therapy, it was such a help to be able to talk to somebody – especially when I found the right guy who talked back and taught me how to deal with all that stuff. It was huge.”

Was it always depression and anxiety?

“Depression, anxiety, stress, that stuff. Really anxiety: being so anxious and stressed over things I can’t control. That was such a tough way to be.”

Throughout your life you have turned to your deep faith. However, houses of worship are not always empathetic to mental health challenges: “Pray it away,” “Too blessed to be stressed,” “Give it to God.” How did you resolve that?

At 27, I would just want to be in that funk… at 57, I know I don’t want to be there

“Churches are great; you want to go there and praise God and everything. But some of the things they do, like what you’re talking about, how mental health is such a stigma – I realized that’s not the answer.

“The answer is getting somebody to help you through this. I realized I could have both. I could still believe in God, and believe wholeheartedly in everything that He's about, but I could also get some help with these things that nothing else seemed to be helping with.”

From the beginning, music has been your core source of pleasure, but in many ways it has been a source of pain because of what the industry throws at artists.

“Absolutely. Some of my lowest moments came because of something said or done in the music world. It’s like faith; it can bring you so much joy and happiness, but it can cut you to the bone also.”

How do you find balance?

“I make sure that life is mostly good, mostly happy, and when the bad times come, you deal with them however you have to. If you have to call your therapist, or meditate, or do whatever, you’ve just got to deal with the bad times. Really, my life’s mostly good.”

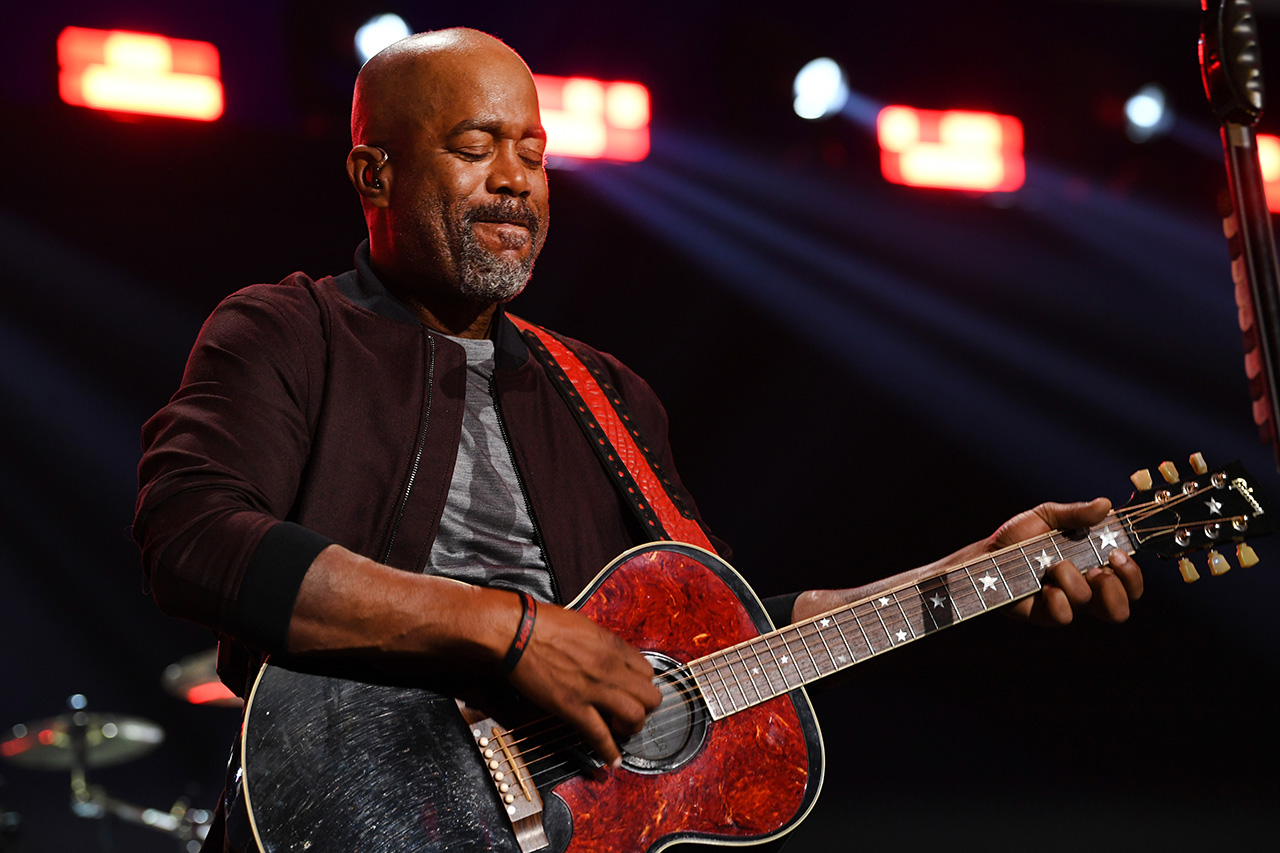

How do music, songwriting and playing guitar help you during those times?

“Music is such therapy for me. If I’m down or sad or something, I pick up my guitar and play a song I love, or I write a song. When I’m writing a song about something that’s bothering me, I find out things. I’ll say something I didn’t know I was bothered about. Music is the best therapy I’ve ever had.”

How does your 50-something self handle these things, compared to your 20-something self?

“My 20-something self would let it creep up on me, and then all of a sudden it was a big explosion and there you are. At 57, I can feel it coming on and try to do something to reverse that feeling.

A lot of the substance use, especially at the end, was because I was trying to escape

“I don’t want to get into that funk. I don’t want my anxiety to start going. I find something to do – therapy, music, something to switch it. Once you get to that point, it’s a different feeling.

“At 27, I would just want to be in that funk: ‘I don’t want anybody to bother me or talk to me. I just want to be here. Leave me alone.’ At 57, I know I don’t want to be there. I want to figure it out. I’m going to go do something to get me out of this – calling my therapist or hanging out with a buddy who’s going to make me laugh and forget about all the stuff I’m anxious about.

“In my 20s I hadn’t accepted it was mental health issues. It was just a bad day. Now I know it’s more than that, and I know how to find help or find something else that will help me deal with it.”

You don’t sugarcoat you struggles and challenges in the book. Was it difficult to decide what you did and didn’t want to make public?

“I always said to myself that if I ever wrote a book, I was going to be totally honest. I went around and around about that stuff, but I couldn't tell the real story if I didn’t put it in there. When I was writing it, I was hoping that somebody who is either in that situation now, or about to get into that situation, realizes you can come out on the other side.

“A lot of the substance use, especially at the end, was because I was trying to escape. A lot of bad days were happening and I was trying to escape from all of it – all of the life. I know now that was totally wrong, but that was what I did then.

“I hope reading the book will help someone do whatever it takes to deal with the things that are bothering them – and not try to hide through drugs and alcohol.”

What would you say to people who are trying to forgive themselves?

“Forgiving yourself for anything is the toughest. My advice would be to find somebody you can talk to. Not who just listens – but who talks back and gives you ways to help you deal with these things that are destroying your head and your day and your attitude.

I realized, ‘I’m saying exactly what I want to say to men everywhere,’ because it’s still taboo to talk about our mental health

“I wrote a song the other day, ‘Just reach out for a little help.’ I’m sure there’s somebody who would love to help you.”

We have to talk about Dax’s To Be A Man; it’s such an important track.

“What a great song! Dax called and asked me to do it. When I cut it, I realized, ‘I’m saying exactly what I want to say to men everywhere,’ because it’s still taboo to talk about our mental health.

“It’s like, ‘Man, pull yourself up. Go on with your life and everything. Nobody wants to deal with it.’ That song has so much truth about being a man and mental health and all that stuff. I wish it would get played more – it’s a really important song.”

Mental health resources

Alison Richter is a seasoned journalist who interviews musicians, producers, engineers, and other industry professionals, and covers mental health issues for GuitarWorld.com. Writing credits include a wide range of publications, including GuitarWorld.com, MusicRadar.com, Bass Player, TNAG Connoisseur, Reverb, Music Industry News, Acoustic, Drummer, Guitar.com, Gearphoria, She Shreds, Guitar Girl, and Collectible Guitar.