Jethro Tull: From Roots to Branches

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Originally published in Guitar Legends

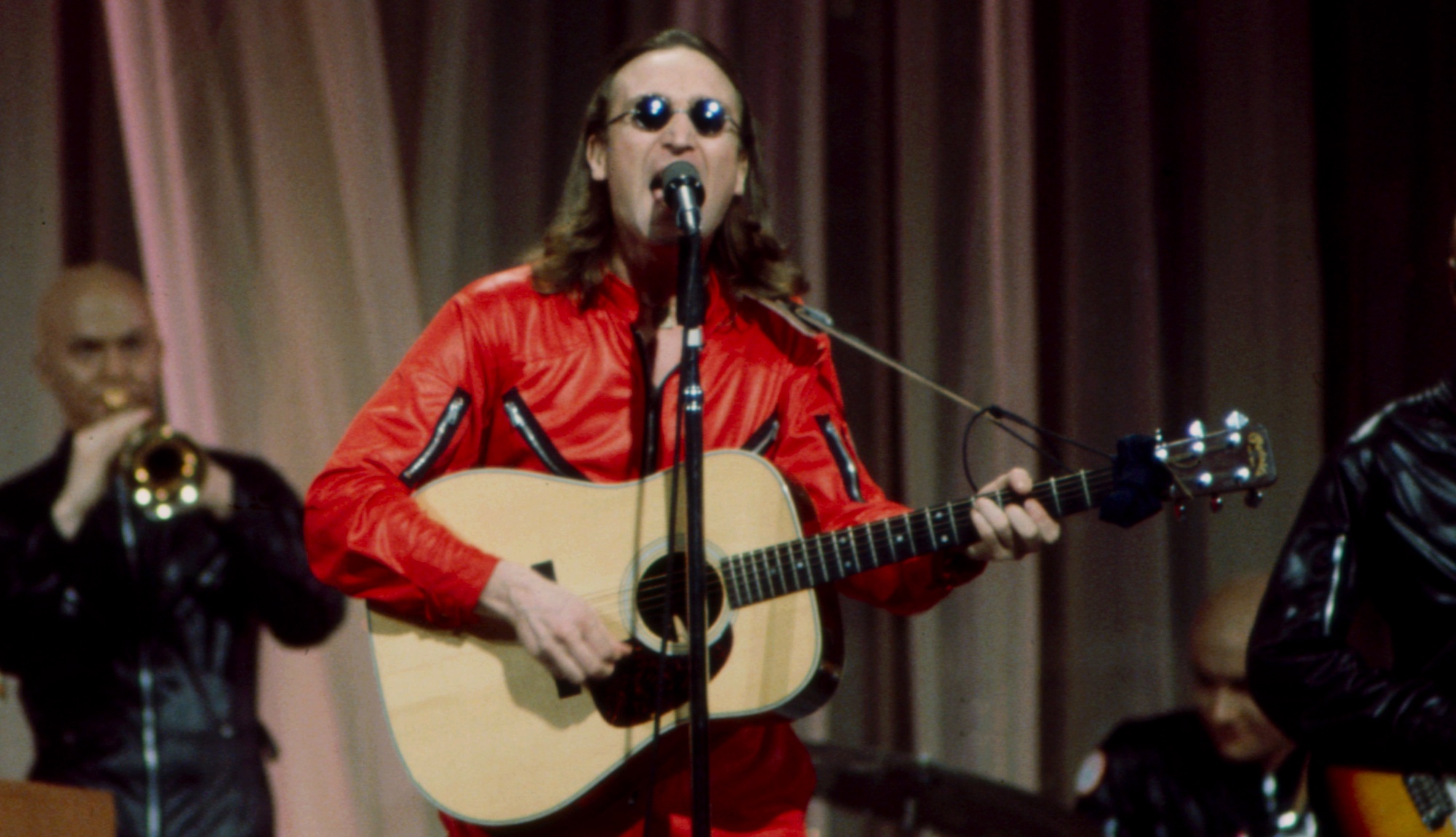

Exploring Jethro Tull’s 40-year family tree of mystical rock greats with guitarists Ian Anderson and Martin Barre.

Jethro Tull’s ongoing standing as a vibrant and enduring live band is no doubt due to its remarkable ability to navigate complex song arrangements while maintaining a wildly paganistic, theatrical edge. How else to explain the fact that, after nearly three decades as one of rock’s most prolific outfits, Tull continues to play to houses packed with loyal legions of fans? The band’s basketful of classic rock hits recorded during its high-water mark in the Seventies certainly hasn’t hurt, either: songs like “Aqualung,” “Bungle in the Jungle” and “Thick as a Brick” are all staples of the live show. Indeed, Tull has taken great pains to only play songs that work well in a concert setting, as elfin frontman and troubadour non pareil Ian Anderson explains: “In most cases, my favorite Jethro Tull songs will be determined by how I feel about them as live performance songs, not by the recorded identity.”

While the band is more often recognized by Anderson’s signature flute-playing abilities and the aforementioned legendary tunes, an underappreciated facet of the Jethro Tull experience is the guitar finesse exhibited by founder Anderson and co-guitarist Martin Barre, the latter of whom has been with the band almost since the beginning—a remarkable feat considering that no fewer than 22 different players have come through Tull’s ranks. These two exceptional guitarists are unsung heroes of the instrument, song-stalwarts whose trademark is to leave flashy, self-indulgent guitar pyrotechnics out of their repertoire and stick to the composition at hand.

Guitar Legends recently caught up with Tull’s twin guitar pillars to discuss the intricacies behind their catalog of greats. As Anderson explains, his creative spark hasn’t waned over the years; in fact, rather than fall into stale songwriting patterns, he has never deviated from his own ruggedly individualistic path—and if that means the hit-song days are long gone, at least Jethro Tull has stayed true to its vision.

“Most people, from their second album on, find it much harder to be as spontaneously creative as they were with their first couple of records,” says Anderson, “and some people only have one thing that they do. Not to be mean about it, but some great rock and rollers, like Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry, are pretty one-dimensional.”

“We Used to Know” Stand Up (1969)

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

IAN ANDERSON We hadn’t played that song live since the Isle of Wight festival in 1970, but we’ve started playing it again recently. When we were in the studio recording it and I strummed up my acoustic guitar and Martin added his bit, it never occurred to me that what we were playing would eventually form the basis of [the Eagles’] “Hotel California.” The melody is not anything like “Hotel California,” of course, but when you actually get to the chord sequence, the way in which the thing harmonically progresses, it is actually the verse of “Hotel California.” The Eagles were opening up for Jethro Tull around that time. However, “Hotel California” is a very, very popular song and “We Used to Know” remains an obscure album track.

MARTIN BARRE We were going for something that we could use as a climax to the live show, an encore or the last number with a big solo. The guitar solo was all done in one take—I just went for broke. In those days I never really sat down and worked out the implications of chord changes. I just played by ear; sometimes I’d get lucky and hit a note that worked and on another take it might be a disaster. I suppose all that early emphasis on solos was a hangover from the jazz era where everybody had their solos. In some ways, it reflects on how boring the music was—but we got away with it.

“Bouree”

ANDERSON I was fortunate enough to hear “Bouree” daily through the floor, because a music student was busy practicing on his classical guitar downstairs from me, so it was kind of stuck in my brain when I was looking for an instrumental piece to play in 1969. We had quite a lot of different arrangements of that piece, but I don’t necessarily remember exactly where it all fits in, especially since some of it is, shall we say, improvisation. I’m really not convinced about all that reading and writing stuff. I suspect that it’s the same with a lot of people who have a temperament better suited to just getting on with it and playing by ear and trial and error. Given the option, I think I would rather learn by ear than off the page.

“To Cry You a Song” Benefit (1970)

ANDERSON I know Martin always likes playing that, but Martin likes a lot of the pieces from the Benefit album. He and I played harmony guitar on that. Basically, it was just a riff piece that I came up with and said, “Here, Martin, this is the riff,” and just left it to him. Haven’t heard that one for quite some time, actually. It’s not one of my favorite songs.

BARRE The influence for that song was Blind Faith’s “Had to Cry Today,” although you couldn’t compare the two; nothing was stolen, it was just a nice riff. The riff crossed over the bar in a couple of places and Ian and I each played guitars on the backing tracks. It was more or less live in the studio with a couple of overdubs and a solo. Ian played my Gibson SG and I played a Les Paul on it. I was playing the song on this current tour at a sound check and everybody sort of turned around and said, “What’s that?” The guys in the band don’t know the music from that era. It’s [Mountain guitarist] Leslie West’s favorite Jethro Tull song. I suppose if there is anybody that ever influenced me at all, West was the one. I felt if I could play like he did, I’d be very happy. Stand Up was a bit nerve-wracking for me, having just joined the band and sort of feeling my way, but Benefit was more fun. I’d become more confident by then.

“Sossity, You’re a Woman”

BARRE “Sossity” had two guitar parts and was the first time Ian and I played together. I remember it very well and which guitar I played—an old Echo acoustic. We played together on that and on “Nothing to Say.” We sat in the studio—I played fingerstyle guitar and Ian played with a plectrum.

“Aqualung” Aqualung (1971)

BARRE In the case of that album, things were very difficult and very tense, but at the end of the day, it was an important album. I think the songs were so good that it really carried the album through. Ian wrote all of it inasmuch as he wrote the riff and the verses. The form was just verse-riff and he had the lyrics. We needed a guitar solo, so I said, “Why don’t we just base it on the chords of the verse, but break it down into half-time, then do a sort of round sequence to do a solo over?” And it worked well. While I was doing the solo, which was going really well, Jimmy Page walked into the control room and started waving. I thought, Should I wave back and mess up the solo or should I just grin and carry on? Being a professional to the end, I just grinned.

“Thick As a Brick” Thick As a Brick (1972)

ANDERSON That was something that derived from things I was fiddling around with while I was on tour in the U.S. I had just purchased my first Martin guitar, and I’m playing it on the song. A small-bodied guitar lends itself—because of its wider fretboard—to the style of playing that allows you space between the strings—they are easily picked. A lot of people sort of assumed that it was a fingerpicking style, but in fact, it was all just played literally as single notes from a plectrum. The album itself was a response to the critical assumption that Aqualung had been a concept album, which it was not, although clearly, there were a few songs that did hang together. Thick was a deliberate attempt to come up with what Saddam Hussein might have referred to as “the mother of all concept albums.” It was all delivered tongue-in-cheek, particularly in terms of its live performance. We delivered it in a way in which people were clearly not quite sure whether it was a very serious exercise or whether it was a bit of light comedy. In truth, it was both of those things.

BARRE There were a lot of songs on that album that we just tied together. We would rehearse a song and then do a link which would go to the next song. I remember staying up working on that album until four or five in the morning, getting a few hours of sleep and then starting again. Very often Ian would come in not knowing what the next piece of music was going to be and we’d just sit down and do it. He’d say, “Got an idea for the next bit?” Other people added ideas and lots of things that John Evan came up with on Hammond organ became classic Tull bits. It was the most difficult music we had played up to that point, as there were lots of odd bars and time signatures.

“Minstrel in the Gallery” Minstrel in the Gallery (1975)

BARRE I’d write a guitar solo for each year, so I wrote one for the Passion Play tour which ended up being tacked on at the beginning of “Minstrel.” The thing about those solos is that they got better as we went along. It was all right for the time, but I’m glad I moved on.

“Salamander” Too Old to Rock and Roll (1976)

ANDERSON It employs one of those hybrid tunings, not really an open tuning, but it has a number of open strings which allows you to play things that you can’t play with a regular E tuning. It was one of the rare occasions when Martin and I actually sat down in a studio and played live acoustic guitar together. The only problem is that you don’t have a lot of time in concert to fiddle with tuning up, because it isn’t just the question of dropping the pitch of a couple of strings. If you do that on any guitar you have to re-tune everything—you change the tension of the untouched strings by virtue of reducing the tension of the strings you are detuning. So it’s not just a 10-second operation, you’re looking at 30-40 seconds to retune two guitars and our band is not very well known for being able to cover for each other while tuning.

BARRE It’s a very difficult piece of music. I remember Ian suggested we do it on a tour. I spent two whole days learning it, because it’s an open tuning and I didn’t know which one it was. It’s not a normal one. It took me hours to work out. I tried three or four tunings before I got it right and then I had to learn it. The result was the best thing we did together.

Since 1980, Guitar World has been the ultimate resource for guitarists. Whether you want to learn the techniques employed by your guitar heroes, read about their latest projects or simply need to know which guitar is the right one to buy, Guitar World is the place to look.