“I was in the studio, and the phone rang. It was Lou Reed. I’d never met him. He called me, saying, ‘I saw a picture of you with this guitar…’” Joe Perry on Aerosmith’s roaring ’70s, writing Dream On – and being a B.C. Rich early adopter

It was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the ‘70s, the era of TV set defenestration, and Aerosmith got bigger, it began to fall apart. Here, Perry looks back on the decade that made them (and near broke them)

In 1973, the band who just a few years later would be known as the “Bad Boys from Boston” dropped their debut album, Aerosmith. Its release set off a chain of events that eventually led to their being nicknamed “America’s Greatest Rock and Roll Band.” And while that’s big-time praise – not to mention one hell of a nickname – you have to remember Dream On is on that debut album.

That said, even though “Dream On” would – eventually – gather more than a billion streams on Spotify alone, it wasn’t enough to catapult Aerosmith to success 51 years ago.

In fact, their debut was so lackluster, sales-wise, that Columbia Records was reluctant to give the band a second shot and only did so if the band’s double-barred lead guitar tandem of Joe Perry and Brad Whitford agreed to allow studio pros Steve Hunter and Dick Wagner to sub for them on 1974’s Get Your Wings.

Looking back on it, Perry recalls being “not happy about it” but understands that you had to take your licks to get by in the biz. “It was just one of those things,” he tells Guitar World. “The record companies were in the business of making money; they didn’t really care how you felt about it. It’s a tough business. It is what it is.

“It was a business, and they didn’t care if they were selling music or selling washing machines, you know? It’s not like you’re walking up to someone with open arms who will give you whatever you need. It was more like, ‘This is how it’s gonna be.’”

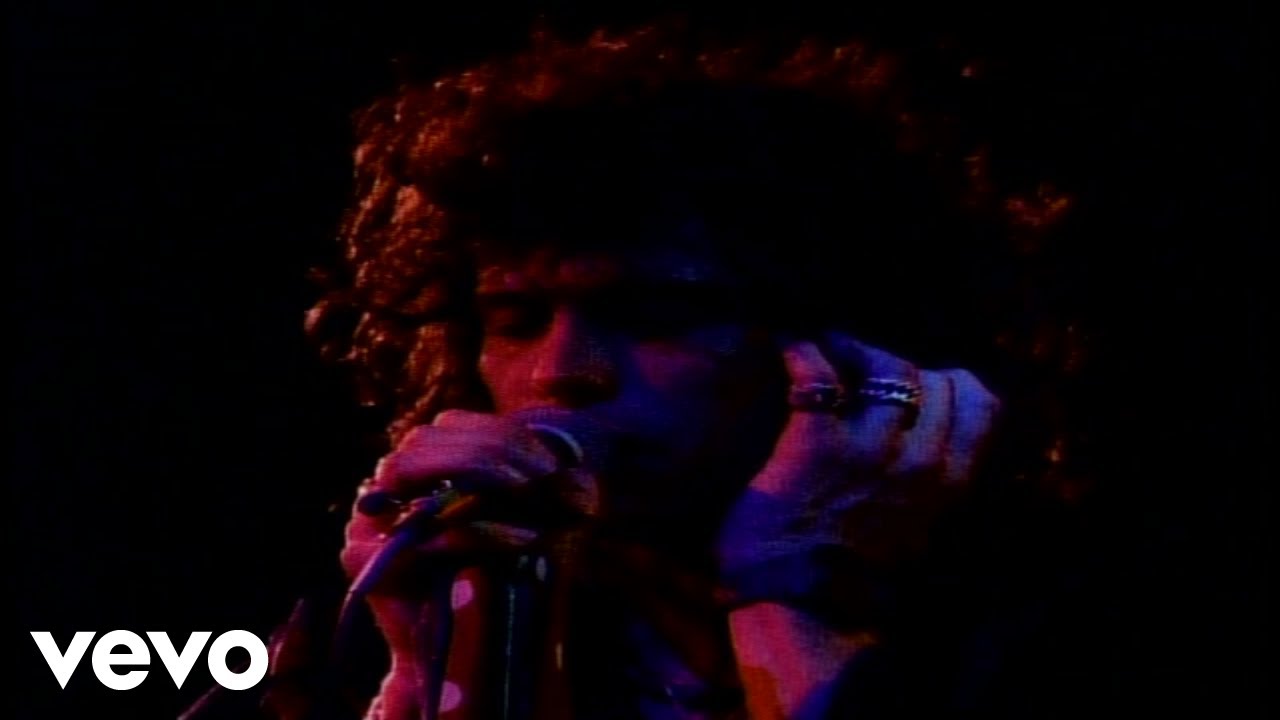

Perry, an iconic guitarist who spent the bulk of the Seventies laying down sleazy riffs and off-the-cuff solos beside his fellow Toxic Twin, Steven Tyler, learned a hell of a lot from the Get Your Wings experience, saying, “We made up for it with the next one.”

Indeed, they did, as 1975’s Toys in the Attic, featuring gargantuan classic rock staples Walk This Way and Sweet Emotion, plus deep cuts like Adam’s Apple and No More No More, blew the damn lid off the thing.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

It was everything Perry and his pals had ever wanted, but they quickly learned that success, while thrilling, was a lot to handle. “I think that’s what ended up taking us down – the shock of it,” Perry says. “It was just our time. But really, the ones that dictated what they wanted were the record companies. They could sit there and say, ‘This is the newest…’ and sign anyone they wanted.”

Success came hard and fast for Aerosmith, as they rattled off two more killer records in 1976’s Rocks – a beloved sleaze-rock staple – and 1977’s Draw the Line – a great record, but one frozen in time as depicting a band going entirely off the rails. Perry says, “Everybody grows up at a different pace, and that’s probably why I eventually left.”

To that end, after the release of 1978’s Live! Bootleg, Perry left Aerosmith in the middle of 1979’s Night in the Ruts, a record he looks back on fondly, even if he didn’t play on all of it.

We just had too much, too soon. We had just kept going since the early Seventies, and the glue that kept us together started to get unstuck

“I wasn’t really mad at them; we just weren’t getting along,” Perry says. “We just had too much, too soon. We had just kept going since the early Seventies, and the glue that kept us together started to get unstuck. We kind of lost the vision and didn’t know what was next. Back then, making it to 27 was like being on borrowed time, so it was tough to live elbow to elbow. It seemed like we’d done everything we hoped to do, and we had no idea what would come next.”

What came next was the near-end of a rock ’n’ roll institution. Perry went on to form his Joe Perry Project, and Brad Whitford left the band a couple of years later. Tyler, Joey Kramer and Tom Hamilton stayed on and hired Jimmy Crespo and Rick Dufay, but it was never the same to most onlookers.

It all worked out triumphantly in the end, and all involved – including the band itself – are alive to tell the tale. But at the time, things seemed bleak. “I remember being quoted as saying that we ‘weren’t ready for the Eighties,’ and that was true,” Perry says. “But personally, even through all the bullshit, we still loved each other, and we still do – you know what I mean?”

“In my heart,” he says. “I never thought, ‘I’ll never play with them again.’ It was just like, at the moment, we just needed a break. I mean, it was a lot of stuff. A lot of stuff together, some good and some bad. That’s just how it was.”

Steven had a version of Dream On in his back pocket coming in. How did you add to that?

“I’m not sure how many of the lyrics he actually had done or what the chords he had were exactly, but we were just learning to play together and figure out what we could actually do.

“I just added what I thought it should sound like on guitar, and would sound great when we played it live, and also gave it a kind of different flavor. I think we made it a little more of a rock thing, and we brought that song to life. We all put those little touches in there and turned it into an Aerosmith song.”

Aerosmith’s debut, Aerosmith, wasn’t initially a hit. Was that tough to deal with, considering how hard you’d worked and how young you were?

“We were getting used to the fact that it was going to be a fight. It took me a couple of years to even… I mean, we were so focused on getting the band to sound the way it should, and we really weren’t even sure what people heard.

“We were a good live band, and I know we were good enough to where people remembered seeing us, but it took a while to get a record contract, and it took us a while to get a manager. So we were pretty used to the fight, and I think that stuck with us. We felt like we had to prove ourselves.”

Considering what you and Brad have accomplished, it’s hard to believe Steve Hunter and Dick Wagner subbed for you on a lot of tracks from Get Your Wings. Was that a tough pill to swallow?

“It was. I look back on it now, and we had Jack Douglas producing it, and Bob Ezrin was involved. Those were the guys [Hunter and Wagner] that were great guitar players and that Bob liked to use. So they had them play on a couple of songs, and Brad and I were not happy about it.

You’ve got to make your own luck. You can’t sit around on the couch waiting for a hit

“This was our last go-around; we had to do it because the record label [Columbia] barely gave us the second record deal. But Bob Ezrin turned out to be a really good friend, and it was nothing personal. Back then, Brad and I were still learning how to work. But we made up for it with the next one.”

You sure did. Toys in the Attic was, and is, a monster. While working on Walk This Way and Sweet Emotion, did you know you were onto something?

“They come out how they come out, you know? I mean… I knew that, well, even after the first record, I knew I could write songs. So I felt like it was just another one. I’ve written other songs I felt were really good, where the tempo is just right, and at different points in our career, it might have been a huge record. I don’t know… so much of it has to do with timing and luck.”

And resiliency, which Aerosmith had in spades from the jump.

“You’ve got to make your own luck. You can’t sit around on the couch waiting for a hit. You’ve gotta go out and do what you can to get yourself in the right position. And then, there’s that last 20 or 30 percent that’s, like, “Holy shit,” and lightning strikes, you know? So much of it has to do with being in the right place at the right time and doing all you can do when you are.”

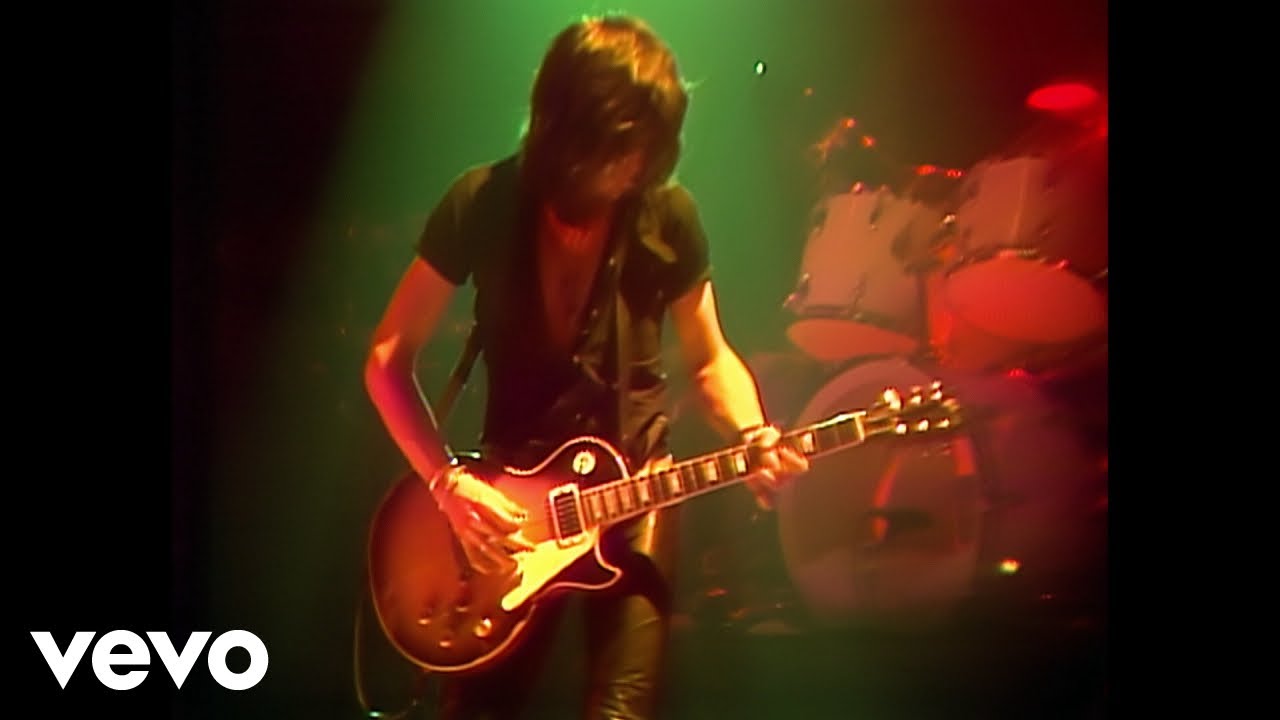

In terms of the gear we hear on Toys, you were using a fair amount of Stratocasters, right?

“I had an old Strat. I remember we were at the Record Plant around the time we were doing Toys in the Attic, and somebody stole my guitar out of the studio. It was my Strat, so I stepped out to buy a new one from Manny’s Music [in NYC], and that was the guitar I used.

“That was pretty much my main Strat for a couple of years, but it’s gone now. To try and find a Strat like that, you’ll pay an arm and a leg for it. They were making pretty good guitars back then. [Laughs]”

Rocks is, more or less, universally loved, with even several members of Aerosmith, like yourself, naming it as the definitive Aerosmith record of the Seventies. A personal favorite of mine is one you wrote called Combination.

“Oh, thank you. It was one I did where I just had this riff kind of thing. It was a real case of seeing what you know and saying and doing what you know.

“I took a few of those things and put them into the lyrics. But I really hadn’t put that vibe into any other song, except for maybe Sweet Emotion. The last bit is kinda like that. That same kinda vibe was coming through – and to a head – on Combination.”

We’d stay in Holiday Inns, and those kinda places because the nice hotels would say, ‘No rock ’n’ roll bands!’

By the time Rocks was recorded, what did your typical rig consist of?

“I was using a [Fender] Twin pretty often, and I had a Fender and a Marshall going at the same time. I’m pretty sure I had a 50-watt plexi at that point, and that was basically all I had in the studio.

“I also had a couple of [Gibson] Les Paul Juniors and the ’59 Les Paul. Those were my main guitars, but I had many. If I wanted a new guitar, I sold or traded another. I remember trading guitars with Johnny Thunders a couple of times back then for a Les Paul Junior.”

These days, you can see what a band is doing on social media 24/7, but it wasn’t that way in the Seventies. Can you paint a picture of what life was like on the road for Aerosmith back then?

“We traveled a lot. You could get from Terre Haute, Indiana to Charleston pretty easily. And then, we’d leave for Atlanta or Tampa and go on to L.A. We really didn’t ever do the tour-bus thing; we went from driving ourselves to flying commercial to chartering planes. And then we’d stay in Holiday Inns, and those kinda places because the nice hotels would say, ‘No rock ’n’ roll bands!’

“Other than that, it was pretty much a show, and it was good. It must have been fun to watch. You’d check in, get your bags, go to the room, do soundcheck, do the show, then go back to the hotel, hang out and go to the next city. And after the show was mostly time spent at the hotel bar, which was a lot of fun.”

Young guys in cities in the middle of nowhere must have been a recipe for all sorts of trouble.

“Yeah, it was. [Laughs] I mean, I think that’s when the TVs started going out the window. But, okay, I know that sounds like fun, but you have to be pretty loaded to do something like that. And then, after you look at the expense reports, I don’t think I got that much fun out of it. I can say I did it, but that was it. It’s so not what I’d do now, but, like you said, we were young guys having fun, and we had nobody to tell us, ‘No.’”

By the time Draw the Line came out in 1977, the wheels were starting to get a little wobbly on the wagon. How would you describe the state of Aerosmith by then?

“A lot of personal stuff that we didn’t let bother us in the beginning was starting to show itself. We were still touring, and we’d get the itinerary and that was it. We’d show up at Logan Airport [in Boston] and I’d be gone. We were getting older; some of us were getting married and some had girlfriends. It’s like when you get older and stop being mad at your parents, you know? All that stuff is part of growing up.”

Draw the Line was still a great album, with an underrated highlight being Bright Light Fright. That always seemed like your answer to punk rock, which was blooming.

“That was really it; I loved punk. I remember when I’d be riding in the limo, or whatever, I’d hear the Sex Pistols or the [New York] Dolls and I’d turn it up. I’d be like, “Yeah, this is fucking rock ’n’ roll, man. This is great. So, Bright Light Fright was about as close as we were going to get to punk. We dabbled in all kinds of music, like country, but that was kinda my version of [punk].”

One of my favorite records is by the Kinks, Live at Kelvin Hall... I remember hearing it, and that’s where I kind of got my education of, ‘Here’s a real good product.’ It made an impression on me because the audience was as loud as the band and exciting to hear

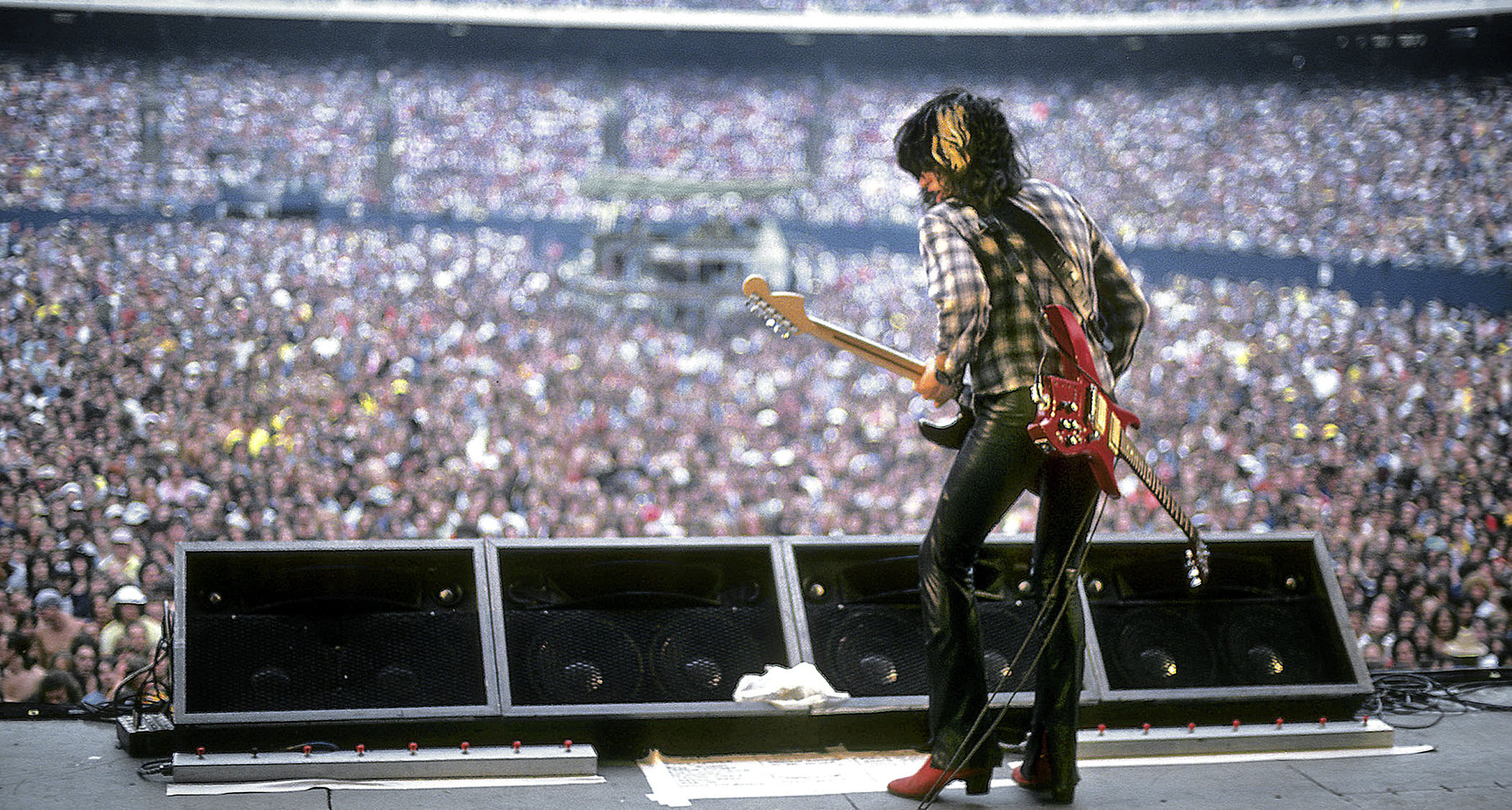

When people think of the guitars you used in the Seventies, your ’59 Les Paul often comes up. But there’s a photo of you from the Live! Bootleg album holding your B.C. Rich Bich. Where did that guitar come from?

“Our sound man, Nite Bob [Robert Czaykowski], hooked me up with a lot of guitars back then. B.C. Rich was making some guitars that didn’t look like Les Pauls or Stratocasters, and there was a quality of build that I liked. There was something about the Mockingbird and the Rich Bich, and Brad bought one, so we were a couple of the first guys to use them.

“I remember being in the studio around then, and the phone rang, and the secretary said, ‘Joe, phone call for you.’ It was Lou Reed. I’d never met him, and he called me, saying, 'I saw a picture of you with this guitar…' That guitar has a distinct sound that doesn’t work for some things, but it sounds great on others. It has a really cool thing about it, almost like a flange thing. It’s really amazing, though it doesn’t work for everything.”

I’ve read that you weren’t sure about doing the Live! Bootleg record, and having it be raw and un-messed with was a dealbreaker.

“One of my favorite records is by the Kinks, Live at Kelvin Hall, which is kind of hard to find. But that’s what I’d heard, and it was probably my first live record. I remember hearing it, and that’s where I kind of got my education of, ‘Here’s a real good product.’

“It made an impression on me because the audience was as loud as the band and exciting to hear. It sounded live and raw, and when I found out that people were overdubbing and ‘fixing’ their live redoes, I was like, ‘What the fuck? I don’t want to do that.’

“If somebody else wants to do that, that’s their business, but I wasn’t down for it. If we were gonna put out something “live,” it should be live. Even down to the cover, we had a band meeting about that and wanted to have the coffee stains and the whole bootleg look.”

You touched on why you left, which happened during the recording of Night in the Ruts in ’79. That must have been difficult, given how much you’d been through with the guys.

“I’ll tell you, at that point, it took a lot. You have to imagine that it was everything you just described. I remember a big part of why I left was not just personal stuff but business stuff. I wanted to do an audit of the business and see where our money was. We didn’t pay any attention to that stuff; we would get checks and put them in the bank.

“We knew we were doing well, and we made sure the taxes were paid and all that shit, but we didn’t have a handle on it. I remember telling the guys, ‘We should do an audit.’ I was talking to the other guys, and it was all part of the business; I’m all for everybody getting their fair share, but I don’t want… it just seemed like they didn’t want to. They said, ‘Everything’s fine.’”

Can you remember when you finally decided to quit?

“One day, I just quit. There was an incident and a big fight backstage, and it was just a bullshit fight. But I also wasn’t happy with what was going on behind the scenes; it felt like we were being told where to go and when to go. Nobody seemed to be looking out for us as far as caring or burning out, and I was trying to get some kind of handle on that.

Like I’ve said before, if we’d had our wits about us, we would have just said, ‘Let’s take a year off’

“So I got my own lawyer and said, ‘If they don’t wanna do it, I’m gonna do it myself. How much did we make last year,’ and blah, blah, blah. There was stuff going on and I wanted to check it out, but I couldn’t get the rest of the guys to go along with it. I finally told my lawyer, ‘Call them up; tell them I’m not coming back,’ and I didn’t. I felt like a huge weight was off my shoulders. I thought, ‘I’m just gonna put a band together, do a record, go out, tour and have fun.’”

In terms of the ’70s, through the highs and lows, what comes to mind when you think back on it all?

“Things went the way they went. Like I’ve said before, if we’d had our wits about us, we would have just said, ‘Let’s take a year off.’ We certainly had enough money to take time off, but there was too much bullshit. We couldn’t get it together to talk to each other like that, so that’s how it went.”

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.