Keith Richards' guitars: a complete guide to the Rolling Stone's iconic instruments

Micawber, Malcolm, Sonny – in the world of Keith Richards, even his guitars are characters. But there is more to his collection than those famous Teles. Thousands more...

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

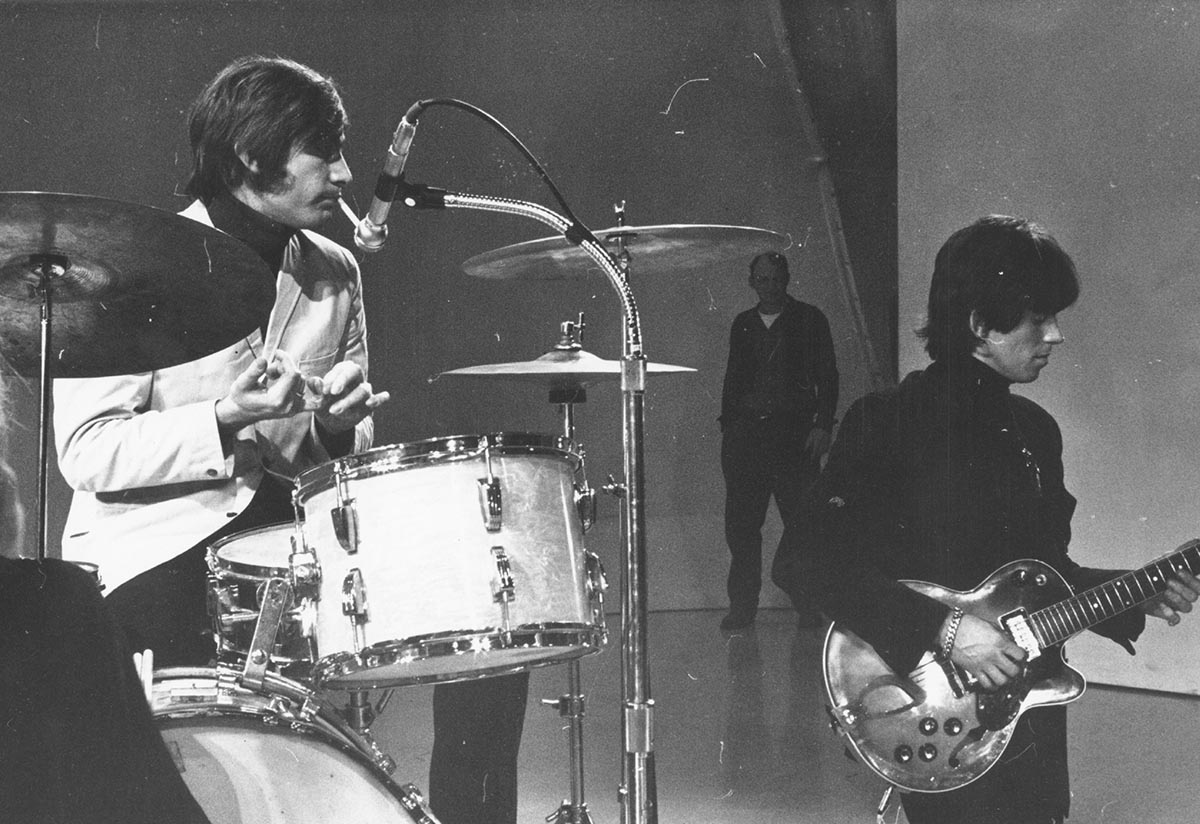

All kinds of rare and special ingredients go into The Rolling Stones’ sound. The rhythm is the backbone, Charlie Watts’ touch and feel on the drum set binding it all together, tumbling between the sinewy and the edgy, the relaxed and the funky.

On top there is Mick Jagger on the mic, that ageless supernova of charisma. Somewhere in the middle you’ve got the strings, where the mojo is cooked up live.

In 2021, that’s Ronnie Wood and the ever-present survivor, Keith Richards, whose judicial taste in vintage guitars and amplification is augmented by an ear for alternate tunings and a playing style that summons ghosts from the Delta to shuttle around louche rhythms, layering melody on top, probing then retreating.

In the studio, an ever more byzantine recipe is followed; their sound is the room, the recording equipment, in the ancillary percussion and strings and how they work in concert. Richards is custodian of this recipe. He is both the hot sauce and the hand on the spoon, mixing everything.

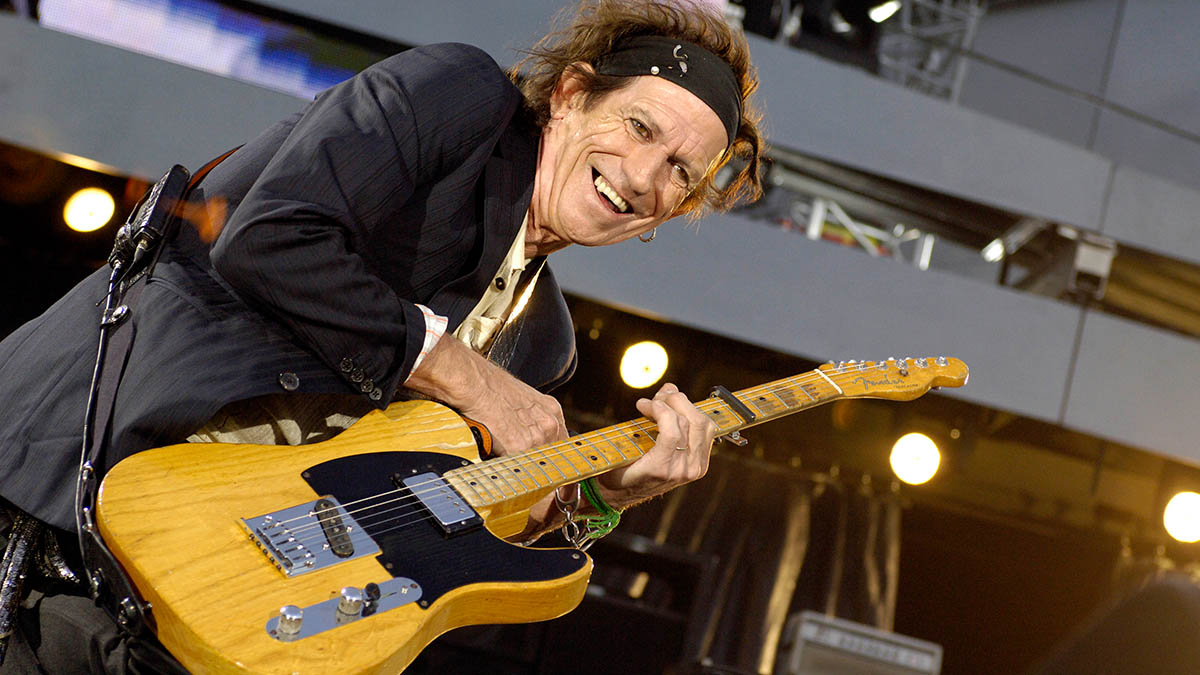

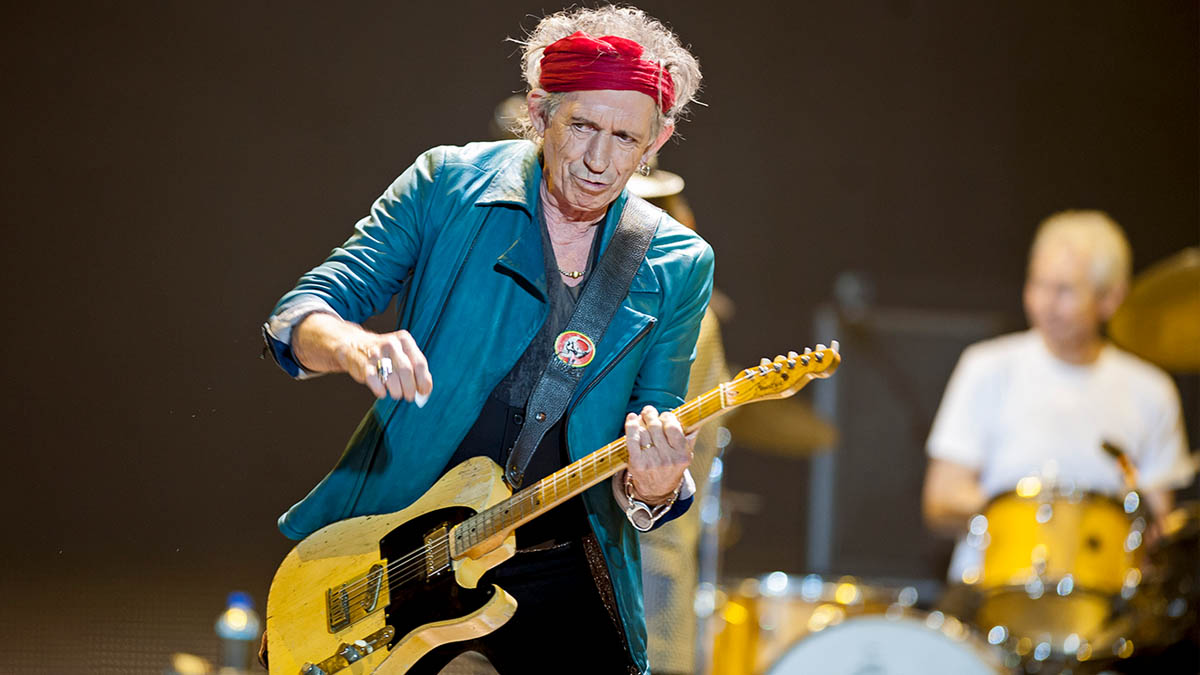

As a guitar player, what is the first guitar you think of when you think of Richards? For many, it has to be the Fender Telecaster, maybe ‘Micawber’, Richards’ number one, the 1953 Blackguard with five strings and a Frankenstein spec, a battered Butterscotch Blonde forever slung at a 45-degree angle from Richards’ hip.

Or perhaps it is ‘Malcolm’, a ’54 model in natural finish that has similarly been augmented, five-strings, left in open tunings. Then there is the black 1975 Fender Telecaster Custom, which made its debut – as did Keith’s new foil, Ronnie Wood – on the Stones’ Tour Of The Americas ’75, or Sonny, the ’67 Sunburst Tele.

But let’s take it back to the beginning because the Telecasters only tell part of the Keith Richards story.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

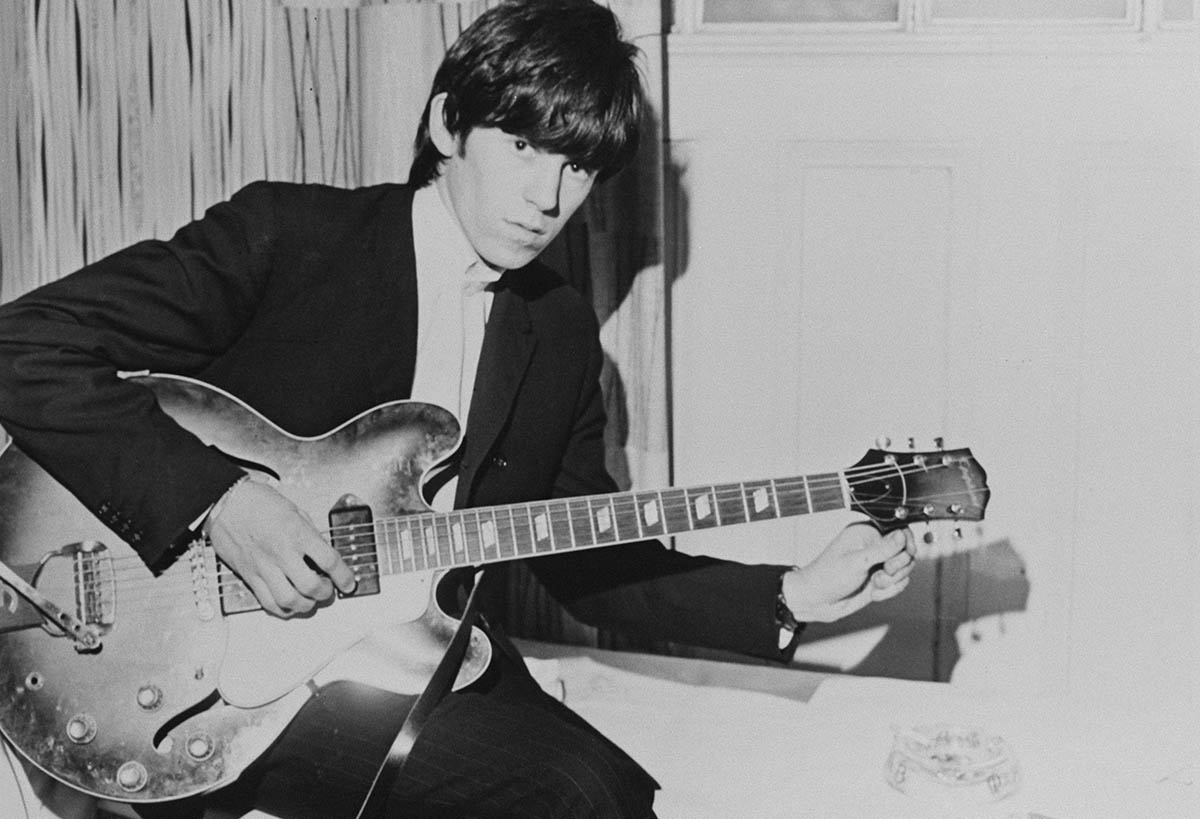

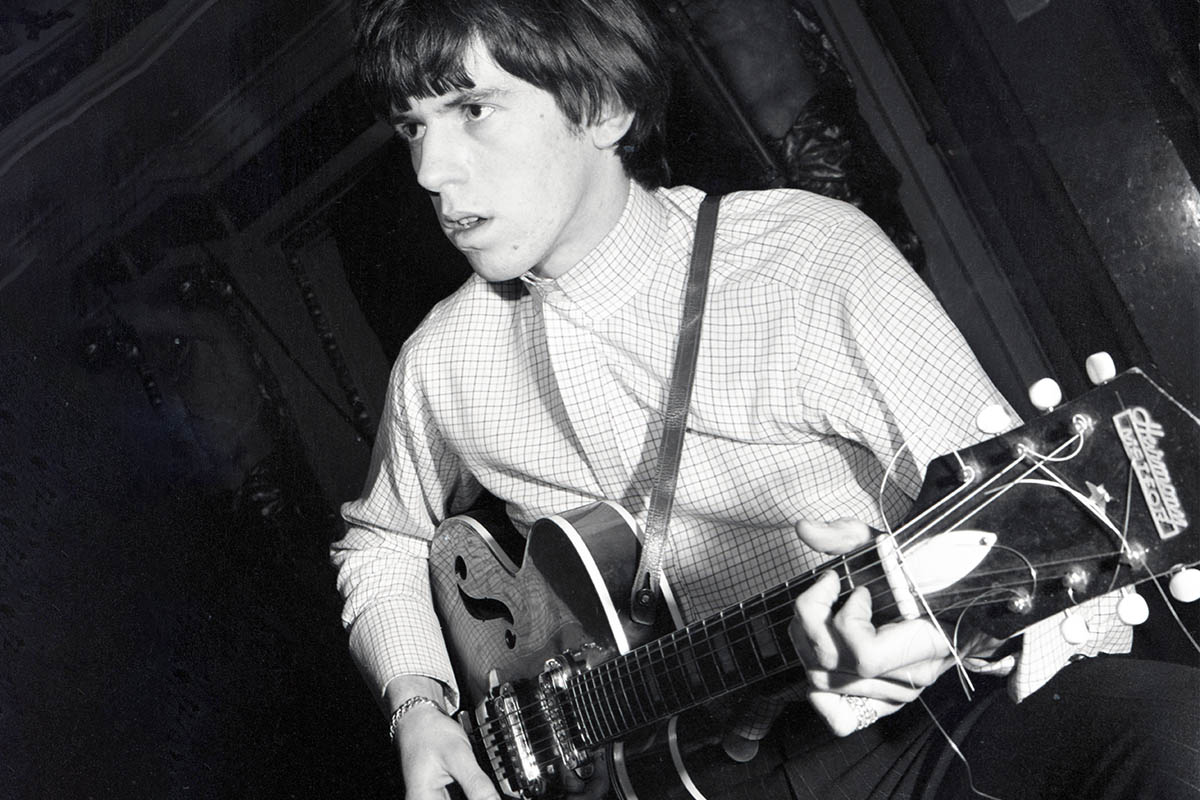

The early days: 1960-’64

The population of Keith Richards’ guitar collection is estimated to range between 1,000 and 3,000 but just like the rest of us he had to start somewhere. His mother got him a Rosetti acoustic when he was around 13. Ten quid was a bit of money in 1959 but it proved a shrewd investment.

Just like the rest of us, he was confronted with Malagueña early on; taught by his grandfather, it was the first song Richards learned. The acoustic would become key, not only to Richards’ playing style but his entire guitar philosophy. He often speaks of the acoustic’s purity. Learn to work it, and only then can you appreciate what it takes to use the electric.

As Richards says, “The electric guitar? All they did was put a phone in it. But it was the right phone at the right time.” For a band with an electric pulse, it is remarkable that so many occasions have called for the acoustic guitar.

When The Rolling Stones parked themselves in Regent Street Studios, in January 1964, to record their debut album, Richards’ electric of choice was a Harmony Meteor H70 that he had bought the year previous. The Meteor had a thin hollow arch-top body of spruce and maple, and a short scale length of 24”.

A pair of gold-foil DeArmond pickups gave the Meteor a raw tone that would become part of the soundtrack to the 60s. Notably, The Kinks’ Dave Davies playing one on You Really Got Me.

The Stones’ self-titled debut showcased the Meteor, but it was his 1963 Harmony H1270 12-string acoustic on stand-out track Tell Me (You’re Coming Back) that suggested that the Stones were not just another beat combo. A 12-string jumbo, the H1270 was an early studio star for the Stones. Richards used it on the likes of Not Fade Away, Good Times, Bad Times and Play With Fire. On Tell Me... Richards let the 12-string and vocals bleed into the one mic. Using as little separation as possible would become a leitmotif of the Stones future recording sessions.

As would the 12-string; its woozy, chorusing quality would jive just as well on the Stones’ more psychedelic jams as it did on the bone-dry directness of Not Fade Away.

In 2004, Richards’ H1270 was sold at auction for $33,460, but if you scour the internet you could pick up a vintage 60s model with an aftermarket L.R. Baggs pickup for 600-odd bucks. Richards’ Meteor was joined by a Kalamazoo-era 1962 Epiphone Casino as the Stones’ career took off.

The doublecut archtop had a fully hollow build of laminate maple and birch, and featured pair of P-90s, plus a tune-o-matic bridge and trapeze tailpiece. If the first two albums were handled by hollow-bodies, Richards would turn to a heavyweight for the recording of Out of Our Heads.

The Keef ‘Burst, Satisfaction and the road to ’69

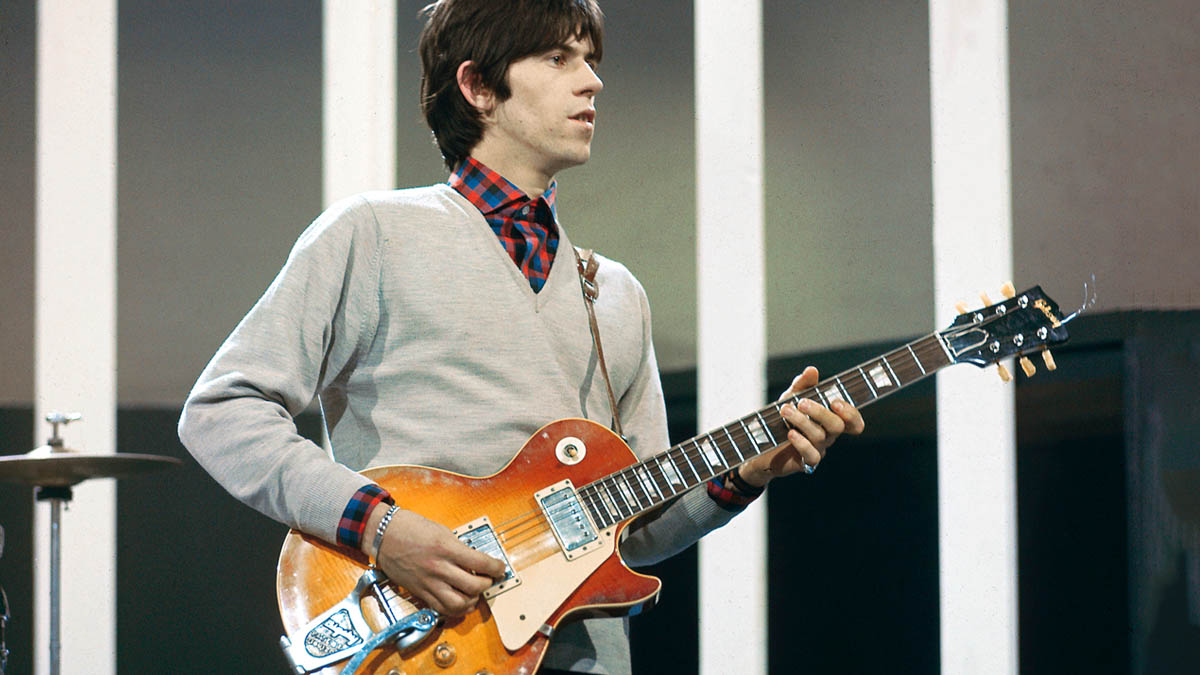

The Keef ‘Burst ushered in a changing of the guard for Richards’ recording guitars. It first made an appearance on the Stones’ 1964 tour, popping up on the Ed Sullivan Show.

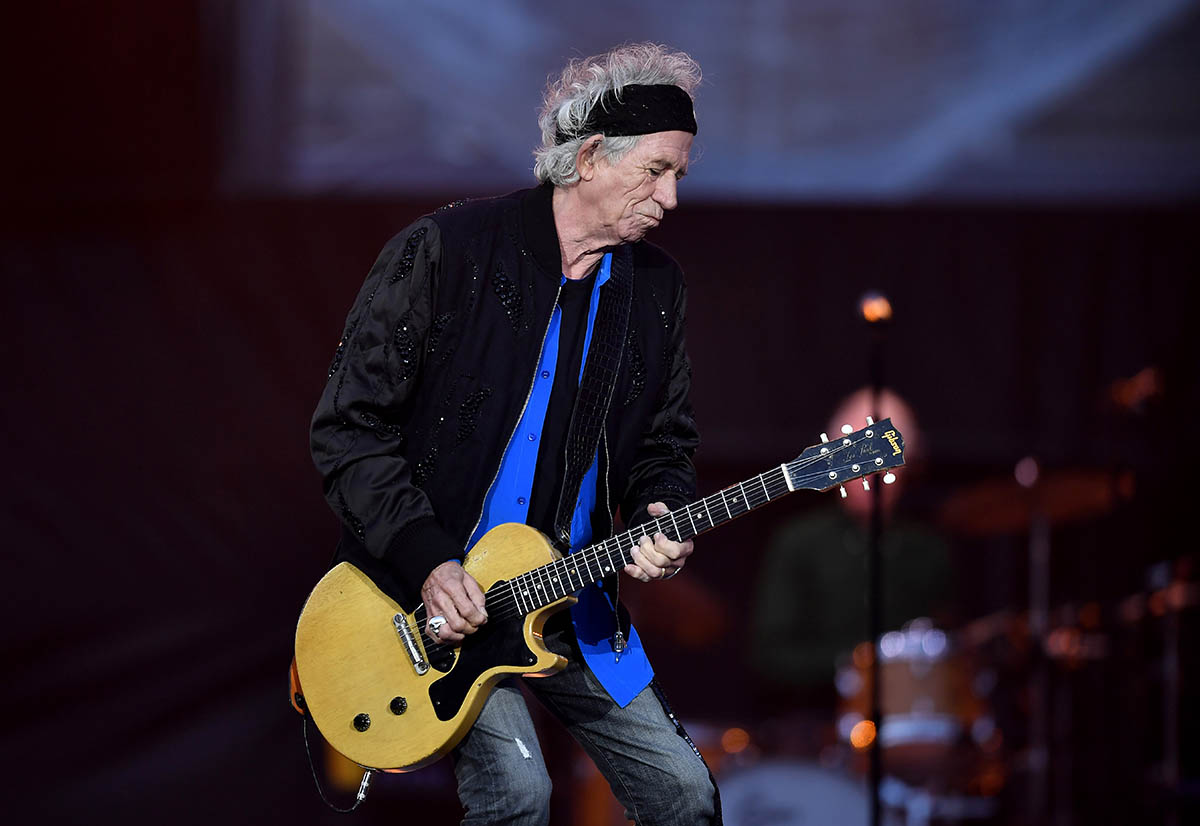

The 1959 Les Paul Standard is the Holy Grail for Gibson aficionados – and priced accordingly in six-figures on the vintage market. The Keef Burst, which Richards took receipt of some time in ’64, was retro-fitted with a Bigsby vibrato. He sold it to Mick Taylor in 1967, only for it to return to the band when Taylor replaced Brian Jones in 1969.

Its final destination is shrouded in mystery, with a collector rumoured to have paid over a million dollars for it, but we do know that ‘Burst maven Bernie Marsden owned it, telling Guitarist, “You know the famous one I let go because it wasn’t as good as The Beast? That was the Keith Richards one.

“It’s not that it was bad. I already had one - The Beast - and I got offered double the money I’d paid for the Keith ’Burst in 1974. I didn’t know it would become a million-dollar guitar. ”

Richards leaned on it heavily for the Out of Our Heads sessions, which assumed huge cultural significance as soon as Richards pressed one of Gibson’s new-fangled Maestro FZ-1 Fuzz-Tone pedals into action for the (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction riff. He had always maintained that it was a horn part, and kismet played its part with arrival of the fuzz pedal.

“The way Otis Redding ended up doing it is probably closer to my original conception for the song,” he told Guitar World. “It’s an obvious horn riff. And when this new Fuzz Tone pedal arrived in the studio from the local dealership or something, I said, “Oh, this is good. It’s got a bit of sustain, so I can use it to sketch out the horn line.”

If the band had hitherto mined American R&B, blues and early rock ’n’ roll for inspiration – for songs to sing, more to the point – 1966 saw the release of Aftermath, the Stones’ first album of all-original material. There was now a sense of danger about the Stones.

Richards was enjoying an open relationship with his guitars, pursuing new sounds. An electric 12-string appeared on Mother’s Little Helper – “some gashed-up job” that he played slide on. Richards was pictured on the cover of the April 1966 issue of Beat Instrumental with a Guild M-65 Freshman, a lightweight hollowbody with a bound maple top and mahogany back-and-sides.

While a spruce-topped Gibson Heritage had been a regular companion on TV spots, come the mid-60s, Gibson’s most brightly feathered dreadnought, the Hummingbird, flew in through his window, and it would leave its mark on wax, most notably on Jumpin’ Jack Flash and Street Fighting Man.

“On Street Fighting Man, there’s one six-string and one five-string acoustic. They’re both in open tunings, but then there’s a lot of capo work,” Richards told Guitar World.

The Stones at their most propulsive, Jumpin’ Jack Flash was recorded with a Hummingbird sharing the mix with another acoustic in Nashville tuning. Richards used his Phillips or Norelco cassette recorders to compress them, changing their character – it was as though the acoustics were resisting their physical limitations.

“I played a Gibson Hummingbird tuned to either open E or open D with a capo,” said Richards. “And then I added another guitar over the top, but tuned to Nashville tuning.”

On occasion, he would play a Gibson Firebird and had started regularly playing a 1958 Les Paul Custom with a custom graphic. This, after all, was the '60s, and they were gathering pace. By the time the band were to hit the States for the notorious 1969 tour, which resulted in controversy, craziness, bloodshed at Altamont and one of the finest live recordings in rock history, Richards had a lot to choose from.

Live, the see-through but super-heavy Ampeg Dan Armstrong Plexi entered rotation, as did a newly acquired 1969 Gibson ES-355TD-SV stereo. Live, Richards used a 1930s National Style O resonator on Prodigal Son and You Gotta Move, and a Martin D12-20 12-string with a DeArmond pickup in the soundhole. He would use a korina Gibson Flying V at the free Hyde Park show, but that would soon disappear.

In 1969, there was a sense that oblivion was on their trail but somehow they held it together. The guitars didn’t always. When tracking Gimme Shelter during the Let It Bleed sessions, Richards used a borrowed a Maton Supreme Electric 777, an ES-150-style electric, and it would turn out to be the last act in its story.

“At the very last note of the take, the whole neck fell off,” said Richards, in Guitar World. “You can hear it on the original track. That guitar had just that one little quality for that specific thing. In a way, it was quite poetic that it died at the end of the track.”

Fender 'Micawber' Telecaster: Keef‘s number one

Everyone would like to and many have tried but nobody plays the Telecaster like Keith Richards. He made the blackguard Tele the coolest guitar on the planet. No question. If the Telecaster is the ultimate rock ’n’ roll guitar, perhaps it was inevitable that it would find its way into Richards’ hands. It was the late 60s when he discovered the Telecaster.

“Around the same time I was getting into Telecasters I was experimenting with open tunings,” he told Guitar World in 2002. “I don’t know why. Maybe it was because around that time, ’67, we started having time off that we didn’t know what to do with. So I started to experiment with tunings.

“Most people used open tuning basically just for slide. Nobody used it for anything else. But I wanted to use it for rhythm guitar... Of all the guitars, the Telecaster really lent itself well to a dry, rhythm, five-string drone thing. In a way that tuning kept me developing as a guitarist.”

Around the same time I was getting into Telecasters I was experimenting with open tunings. Most people used open tuning basically just for slide. But I wanted to use it for rhythm guitar...

Micawber is his most-famous Telecaster. A 1950s Tele in Butterscotch Blonde, it was a 27th birthday present from Eric Clapton and soon found itself decamped to Nellcôte as the Stones took shelter from the UK taxman under the hot sun in the South of France. Exile On Main St. was brewing, and Micawber was there from the ground up. That’s when the toolbox came out. The low E string was removed as Richards continued his exploration into open G tunings. Further modifications changed the menu.

A Gibson PAF humbucker was installed at the neck, a pedal-steel pickup at the bridge. Fundamentally, it a ’54 Tele with a ’52 Esquire neck, Micawber (which takes its name from Dickens’ David Copperfield) is a triumph of Richards’ whatever works ethos, but it arguably kick-started the aftermarket for Fender modifications.

In the '80s, Richards’ tech Alan Morgan sourced a brass bridge plate and saddles to make it more roadworthy. With no saddle for the sixth string, Richards’ number one Telecaster is a specialist instrument tuned G D G B D for songs such as Brown Sugar, Honky-Tonk Woman and Can’t You Hear Me Knocking.

The 1970s and era of modification

Turning 27, a cursed age for any musician of the era, deserved some celebration. It was Eric Clapton who did the honours, gifting Richards the 1953 Fender Telecaster that would be retooled and renamed as Micawber. Others soon followed. Richards sought out new ways of articulating rock ’n’ roll in the electric guitar’s most primitive dialects. Take the Gibson Les Paul Jr, aka ‘Dice’.

Finished in TV Yellow, this primordial doublecut would become a regular onstage by the decade’s end, using it notably on Midnight Rambler – a live highlight that was often performed with the Dan Armstrong before.

He would layer play a Junior with a Tele when recording Start Me Up in 1981. Travis Bean guitars, with their aluminium necks, caught Richards’ attention. If you don’t suffer from motion sickness, you can check out the promo video for She’s So Cold to see Richards with a black TB500 (one of 351 produced).

In 1974, he started using a singlecut Zemaitis with skull-and-bone graphic. As with the Telecasters, Richards nixed the low E. The Zemaitis, aka ‘Macabre’, housed a single PAF humbucker at the bridge and, again, offered Richards the simple pleasures of an electric guitar with nothing in the way.

The lesser-spotted Richards has never been a big Strat player, but he does own a Mary Kaye Strat, and through the '80s and '90s played the next best thing, a Music Man Silhouette. Some of Richards’ guitars rarely see the light of day, such as his Gibson ES-350 – a big-boned jazz-box with a natural finish and with the all-important Chuck Berry connection.

“I’d be too afraid to take it onstage,” he said during an Ask Keith Q&A from 2003. “I’d be afraid of breaking it by making a silly move, and it’s a big guitar. I love it for the studio. I love it in the dressing room. It is such a beautiful all-round sound.”

The ES-350 makes rare public appearances, and was used in 1990 to record Oh Lord, Don’t Let Them Drop That Atom Bomb On Me with Watts, Bobby Keys, Bernard Fowler, Chuck Leavell and the Uptown Horns, a track that turned up on the Charles Mingus tribute, Weird Nightmare.

Looking at Micawber, Malcolm and Sonny, and seeing the road miles on them, it’s understandable that some of that good stuff is saved for the studio. A Rolling Stones show is not the place for tender mercies.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to publications including Guitar World, MusicRadar and Total Guitar. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.