Producer Ken Scott on the making of David Bowie and Mick Ronson’s most iconic albums

Scott takes us back to a febrile moment in rock history when David Bowie and the trailblazing Mick Ronson’s talents combined for Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust

David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, to give it its full title, celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. It’s the record that cemented Bowie’s status as an international superstar, selling more than 7 million copies, and it is second only to Let’s Dance [1983] in terms of Bowie’s most successful records.

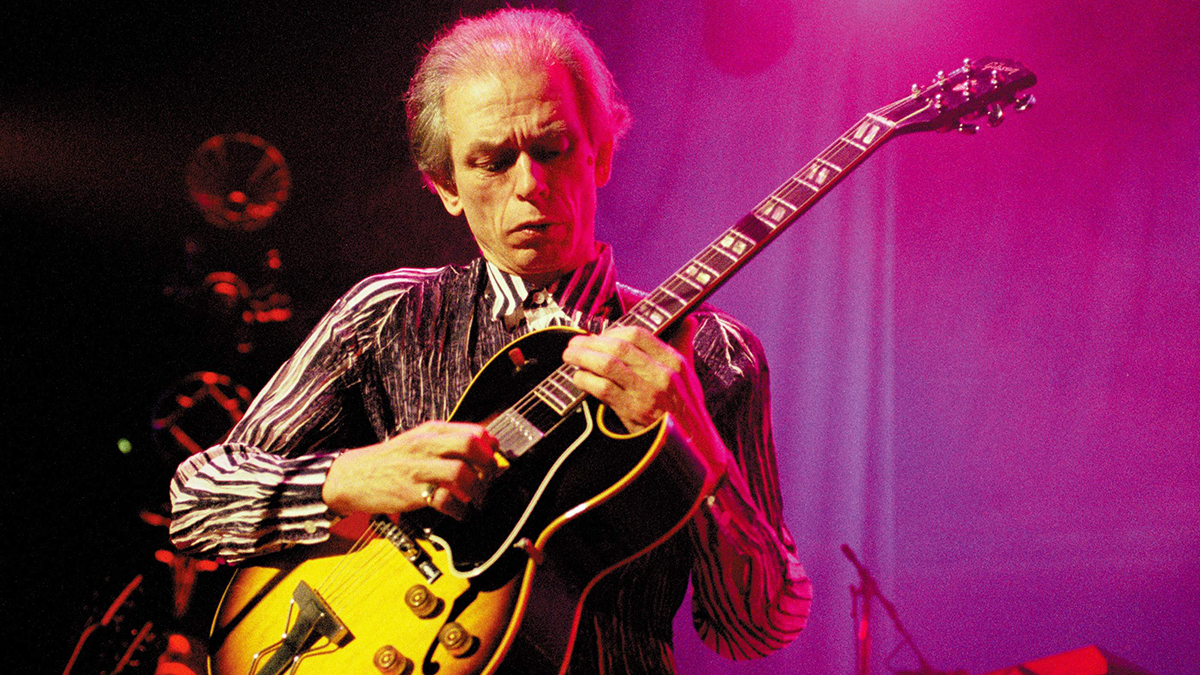

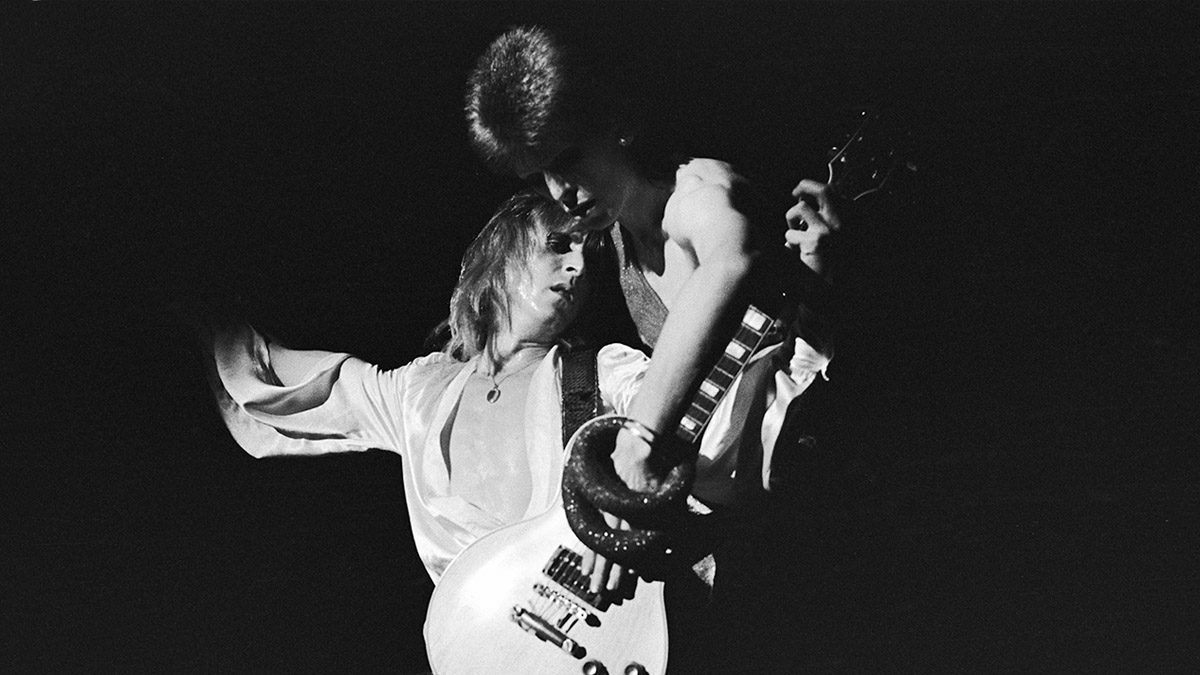

Key to Bowie’s rise to prominence was the work of guitarist Mick Ronson, the perfect visual and sonic foil for Bowie’s unique vision.

At the helm for Ziggy was producer Ken Scott, who’d engineered a couple of Bowie’s albums when Tony Visconti was producing. Scott’s own story reads as the unlikeliest of tall tales. Applying for an apprenticeship in recording and engineering, his first job after leaving school was working as a trainee engineer with the Beatles.

He went on to engineer most of their albums as well as work on countless legendary rock, pop and fusion records. These days, he’s a visiting professor in the School of Film, Music and Performing Arts at Leeds Beckett University in the U.K.

You first worked as producer with Bowie on Hunky Dory before producing Ziggy with him. Tony Visconti produced the previous two albums with you engineering. How’d you step into the producer’s chair?

“There’s something in general that happens to a lot of engineers where you’re sitting next to the producer and you’ll make an 'artistic' comment, which the producer will put to the band. If it works, it’s always the producer’s idea; if it doesn’t, it’s the engineer’s idea. [Laughs] We tend to get fed up with that and I’d reached the point where I was having to think about the engineering process less and less; it had become second nature to me.

“I wanted to make the move and I happened to mention to David that I was planning to move into production. He said he’d just signed a new management deal and was about to go into the studio and [asked] if I’d like to help him. That was Hunky Dory [1971], and we continued for another four albums.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Having worked as an engineer while Visconti was producing, did anything that he did inform your own process?

“It did. I worked in a completely different way to Tony. On the first two albums he did with David, Tony was the bass player, the musical director, the arranger and the producer. My feeling about David, having worked on the first two albums, was that he was a really nice guy who obviously had a certain amount of talent, but it ended there because the albums weren’t his.

“He wrote the material, of course, but the impression I had was that he had very little say. It became obvious, after David’s time off from the first two albums, that he wanted to get things on track. He hadn’t had any real success since Space Oddity [1969], which was very much focused on David’s ideas.

“I learned my craft as a producer from George Martin and Gus Dudgeon. They always believed very much that the talent was in the studio and that their job was to create, and the producer’s job was to enable that to happen. If something didn’t seem to be working, I’d just encourage him to put all his ideas out there, whether they worked or not. Of course, I’d say they did work most of the time.

“David was so good at putting together a team that could convey what he wanted; at that time it was Ronno [guitarist Mick Ronson], Trevor Boulder [bassist] and Woody Woodmansey [drummer].

“Later he’d switch things around when he wanted to get more of an American sound and put together an incredible American team. What was interesting about David is that he didn’t feel like he needed to control the team he’d put together because he knew what they were capable of and what they’d bring to a project.”

Was he more confident in dealing with you than he was with Visconti at that time?

“Yes, I think he felt I’d be more receptive and open to things. But I think when you say 'confident', I don’t think either David or I were confident in the least when we first sat down in the studio for Hunky Dory, but as things started to come together and we were thinking that things were really working, we started to gain in confidence. But we were both exceedingly nervous initially.”

A lot of the time David just came into the studio, talked the band through the song, played it on an acoustic guitar and then they went for it

When David was preparing the songs for Ziggy, did you hear them in advance as demos?

“The whole Ziggy thing was strange. The time that my feelings about David as a talent really increased was when he, his wife and his publisher came to my house and we started going through tapes of demos for our first album together. It became obvious that there was much more to him than I’d seen from the first two albums.

“I heard a lot of material and we narrowed it down to what became Hunky Dory. I may have also heard some of the Ziggy stuff at that time, but I don’t remember. The thing is that we went on to Ziggy so quickly after Hunky Dory, maybe a matter of weeks, so there was no time to listen to material. A lot of the time David just came into the studio, talked the band through the song, played it on an acoustic guitar and then they went for it.”

Was Bowie a quick worker?

“We had to be. Hunky and Ziggy were recorded in two weeks each. 90 percent of his vocals on the first four albums were first takes, beginning to end, without anything else needing doing to them.”

Did Mick come up with his own parts?

“There was the occasional thing David might suggest, but more often than not, Ronno would just go down to the studio and lay down exactly what he thought was needed, and it nearly always worked. When it came to solos, he’d nail them on the first take all the way through. He may have worked on ideas away from the studio, like the harmonic ideas and fills, but when he was there he got straight down to business.

“He was still [using] that big, old Marshall and the stripped Les Paul, going through the Cry Baby. That was basically his live rig as well. He’d plug into the Cry Baby, slowly open it up from the bottom, find the sweet spot and just leave it there. That would be it for the song, and that was basically what he did for every track I saw him record.”

You’ve worked with a lot of great guitarists. How do you rate Ronson?

“I think he was very underrated. He was exceedingly important to David’s success. David was so talented that I think he would’ve made it no matter what, but Ronno was a very important part of David’s recorded sound and, of course, he looked great on stage with David. Ronno was initially a bit scared of the glam look and the makeup at the beginning, but eventually he came around to it when he realized it didn’t stop him getting women. [Laughs]”

The life of an album was under a year; nobody ever thought we’d still be listening to those songs 50 years later

50 years down the line, how do you think the album stands up?

“It depends on my mood. [Laughs] Some days I love it, some days I hate it and I want to change the sounds on everything. I think with hindsight there are a lot of things I’d like to change, but I certainly wouldn’t ever want to change any of David’s performances. Same with Ronno’s parts. I think, looking back, the drum sound is the main thing I’d change.

“Perhaps, though, if we’d done anything differently back then, maybe it wouldn’t have turned out so well and we wouldn’t be here talking about it half a century later. It’s a snapshot of its time. When I listened to it back then, it was an album every six months, and if people were still talking about the previous album by the time the next one came out, you’d done your job.

“The life of an album was under a year; nobody ever thought we’d still be listening to those songs 50 years later. Rock ’n’ roll wasn’t even that old when we recorded it. There are tracks on some of the other early Bowie albums that I think are better than some tracks on Ziggy, but that is definitely the album that holds together and works best as a cohesive collection of songs.”

You’ve been involved in countless historic albums, including much of the Beatles’ catalog. Were there times when you felt like a frustrated producer, thinking, “I’d do this differently from George Martin”?

“No, never. I was learning how to be an engineer at that point, and I’m very much a believer that you need to focus on one thing and do it to the best of your ability and knowledge and take it as far as you can before moving on to the next thing.

“When I was engineering with the Beatles, I was just trying to learn what the hell I was supposed to be doing. I’d never even been behind a mixing console before I’d worked with them. It wasn’t until just before Hunky Dory that I started to get fed up with ‘just engineering’.”

When I was engineering with the Beatles, I was just trying to learn what the hell I was supposed to be doing

It must have been quite a shock to the system to start an apprenticeship in the recording industry with the biggest band in the world.

“Starting out as an assistant engineer on the sessions – button pushers, as we were called – that feels great, but your job isn’t that important, really. You’re just loading tapes and hitting ‘play’ or ‘record’. But not long after that, to be actually sitting behind the mixing console helping to get the sounds was absolutely ridiculous, but luckily for me it worked.“

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.