The life and times of Jamaican guitar legend Ernest Ranglin

The king of ska guitar, Ranglin helped define the island's sound and took it global

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Legend has it that the genre name “ska” – Jamaica's mid-'60s precursor to reggae – was coined to describe the sound of Ernest Ranglin's guitar. When I interviewed the seminal Jamaican guitarist in 1997, he had this to say on the matter:

“I invented the music, but not the word. And even reggae – I didn’t invent that word either, but I invented the music.”

To someone unaware of Ranglin’s immense contribution to the history of Jamaican music, this statement might seem boastful. But if you dive deep into the island’s formidable musical legacy, you’ll find the compelling rhythmic skank and muted-string poetry of Ranglin’s guitar on countless landmark tracks.

He has worked with many of the greats — Bob Marley, Bunny Wailer, Toots and the Maytals, Burning Spear, Jimmy Cliff, Desmond Dekker, the Melodians, the Gladiators and numerous others. He was the first-call session guitarist and arranger for all the key producers who shaped Jamaica’s trifecta of popular music genres – ska, rock steady and reggae – Clement “Sir Coxsone” Dodd, Prince Buster, Lee “Scratch” Perry and Island Records chief Chris Blackwell.

When you consider the numerous ska revivals that have taken place worldwide since the '60s, and also factor in reggae’s tremendous influence on rock music, it’s an inevitable conclusion that a legion of guitarists owe a stylistic debt of gratitude to Ranglin.

The Specials, the Selector, Madness, the Clash, the Police, the Slits, the Ruts, Rancid, No Doubt, the Slackers, Hep Cat, the Mighty Mighty Bosstones, Reel Big Fish, Sublime... the list goes on and on. All these groups and more can trace some portion of their guitar aesthetic back to Ranglin’s pioneering work.

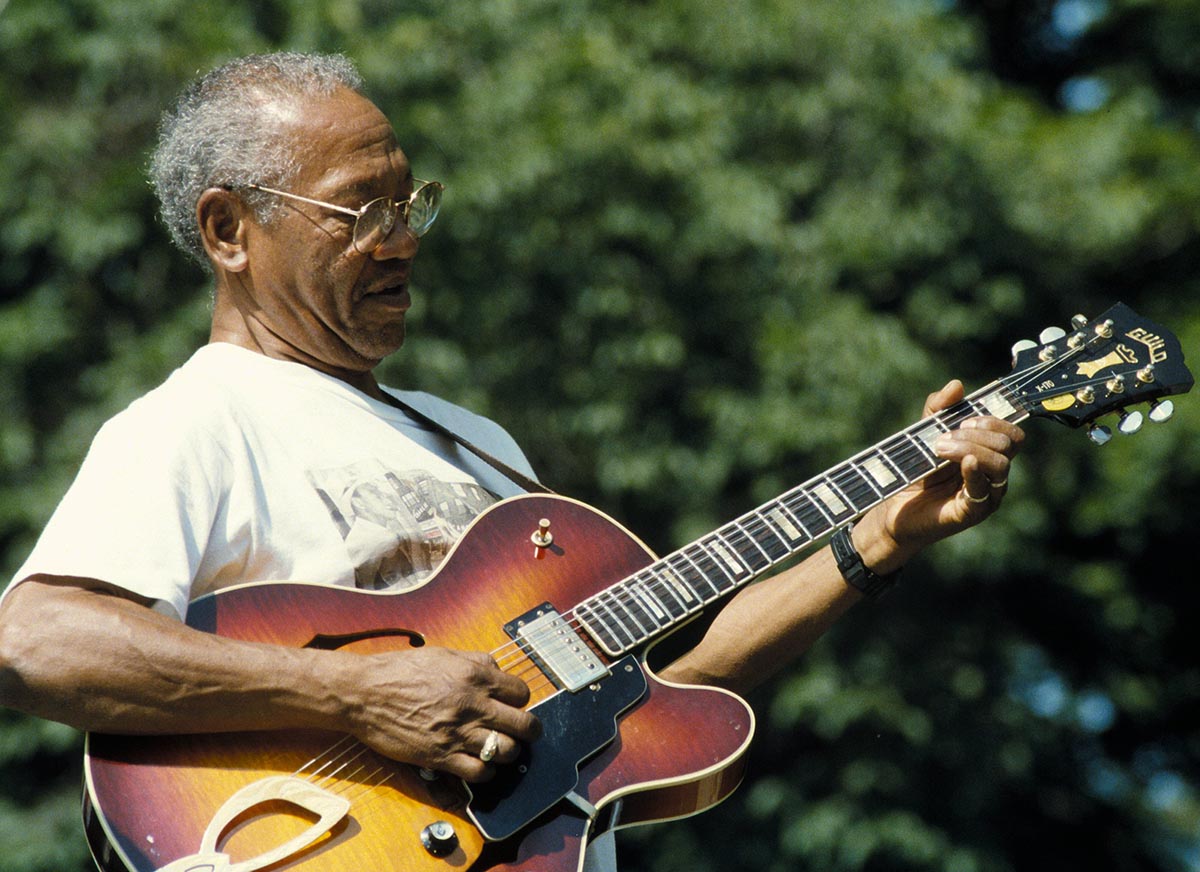

Ironically, though, Ranglin’s first love is jazz. That’s the music he started out playing and has returned to over the years.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I was really an ear player at the beginning,” he told me. “I didn’t really start to study the instrument professionally until I was 14. I used to like to listen to Louis Jordan, Erskine Hawkins, Bill Doggett and people like those. But I would also hear Lionel Hampton, and that’s where I started to hear Charlie Christian and Benny Goodman and those people. When I was a little older, about 15, I began to play in big bands. They would make stock arrangements of their recordings, so we could play just what they did.”

Ranglin and his contemporaries played the kind of gigs available to Jamaican musicians back then – hotels and cruise ships. It was music for the island’s predominantly white tourist trade, for the most part. This influence – a “tropical”, Latin-tinged, mid-century cocktail jazz vibe – can be heard on a record that Ranglin played on in 1959: Lance Heywood at the Half Moon Hotel.

It was the debut release from Island Records – a modest beginning for the legendary label that would bring reggae greats like Bob Marley, Burning Spear and Black Uhuru to international acclaim in the '70s.

Ranglin and Island chief Chris Blackwell became close musical collaborators. Island’s second release, in 1960, was Ranglin’s solo debut album, Guitar in Ernest, a set of jazzy instrumentals that showcase some of Ranglin’s nimble fretwork.

By this point, he’d also embarked on a busy career as a session guitarist and arranger, first at Federal Recording Studios in Kingston and then at the Jamaica Broadcasting Company (JBC) Studios. It was during his time at Federal that he met and began working with another legendary figure in Jamaican music, the aforementioned gun-toting, visionary record producer/entrepreneur Clement “Sir Coxsone” Dodd.

Dodd is the man who signed Bob Marley, as part of the vocal group the Wailers, to his Studio One record label in 1963. Marley and his fellow Wailers – whose ranks also included Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer – joined a growing roster of artists on Dodd’s Studio One record label. As Studio One’s house arranger, Ranglin anchored the studio group, the Skatalites, that accompanied Marley and the Wailers on their debut Studio One single, Simmer Down, backed with It Hurts to Be Alone.

Marley had previously released a few singles as a solo artist on another label, Beverley’s. But they had met with only modest success. This first session with Dodd and Ranglin would yield a far more satisfactory result. Ranglin told me he could immediately sense Marley’s enormous potential; the two would work together again.

“I can say, right from that first time, Bob was a very studious guy. He knew where every guy was going to sing their harmonies. They had to have the notes right. Bob was very serious about it. I could see he was going to be a star.”

One side of the Wailers’ debut single for Coxsone’s label was the doo-wop influenced ballad, It Hurts to Be Alone, featuring some lyrical guitar embellishments by Ranglin. It was the flip side, however, which proved to be the money shot. Simmer Down has become an anthem and a ska classic. A plea for non-violence addressed Jamaica’s sharp-dressed, razor-wielding “rude boys,” the song’s irresistibly danceable rhythm was then sweeping Jamaica and would soon enthrall the whole world.

It was called ska. The rhythm had been brewing a while in a Jamaica newly liberated from British rule. It was fueled by American R&B sounds blowing over the Gulf of Mexico from New Orleans radio stations, which Jamaicans could pick up on a brand new invention of the day – the transistor radio.

From boogie-woogie, pioneering Jamaican musicians like Ranglin adopted what would become one of ska’s defining characteristics: eighth note accentuations on the offbeats of a 4/4 measure. You can hear the boogie-woogie influence clearly on an early track like Laurel Aitken’s Boogie in my Bones from 1959.

But the Jamaican players imparted a uniquely Caribbean swing to the rhythm. The two and four beats were stated more emphatically. The drummer’s kick and snare would often mash down the two and four together, rather than playing on alternate beats as in many other pop music styles.

“It’s a shuffle,” Ranglin explained. “Same thing they used to play in boogie-woogie. The only thing is we emphasized those beats a little more. That was the only trick.”

On many early ska tracks, brass instruments would play the eighth note offbeats. But the role is really tailor-made for an electric guitar. Scraping a pick across six strings, you can create a wealth of rhythmic nuances and ornamental fillips. Ernest Ranglin is the great originator of that whole rhythmic vocabulary – one that he helped pass down to many guitarists in Jamaica and worldwide.

It’s a shuffle, same thing they used to play in boogie-woogie. The only thing is we emphasized those beats a little more. That was the only trick

As part of his duties as Studio One’s house arranger, Ranglin also put together the legendary ensemble whose very name is synonymous with this style of Jamaican music – the Skatalites.

By the time they formed in 1964, most of the players had already worked together live, backing mento (Jamaican calypso) singer Lord Tanamo. So it was a natural choice for Ranglin to call on these musicians when Coxsone came to him with a big project.

“There was a young singer from Trinidad by the name of Jackie Opel,” Ranglin related, “and Coxsone asked me to do an LP for him. So I got this band together. And when the LP was finished, I say, ‘Why not just keep this band?’ Because they had a nice thing going.”

Ranglin was a particularly close friend and mentor to Skatalites saxophonist Roland Alphonso. An educator as well as musician, Ranglin played a role in developing the fluid, playful, beguiling style that became Alphonso’s signature mode of soloing within the Skatalites.

“Roland came from military school,” Ranglin explained. “And they only played classic marches and semi-classic things. So when he came out, he didn’t know anything about jazz, swing ... whatever it was called.

“At the time, I was a big fan of Charlie Parker and [Roland] was an alto player like Charlie. That’s where I gave him a styling and gave him ideas. I gave him harmony lessons and showed him what to do – styling, you know. He was a good [music] reader, because he came out of school learning to read. So I could always write things out for him. We were always together, from young boys, you know.”

The Skatalites lineup was somewhat fluid. But, along with Ranglin and Alphonso, the core, classic members included reedmen Tommy McCook and Lester Sterling, trombonist Don Drummond, trumpeter Johnnie Moore, pianist Jackie Mittoo, bassist Lloyd Brevett and drummer Lloyd Knibb.

Concurrently with their duties as the Studio One house band, the Skatalites recorded and performed as an instrumental group in their own right. Their original compositions and wry covers of American television and film music themes – Bonanza, Guns of Navarone – became huge favorites in Jamaica.

As studio session groups go, the Skatalites rank right up there with the Funk Brothers, who played on countless Motown hits, and the Wrecking Crew, who played on hits produced by Phil Spector, Brian Wilson, Lou Adler and others who defined the pop sound of the Sixties.

Coxsone’s house band was a tight, disciplined and creative unit that could nail a track in just a single take. At Studio One, the work pace was frenetic, and sometimes interrupted by bouts of gunplay in the control room. This is something else Coxsone had in common with Phil Spector.

“With Coxsone, we could turn out at least six tunes a day,” Ranglin told me. “Sometimes we’d do everything [i.e., vocals and instruments] together, and other times we’d do the tracks first and the vocals after.”

Even with his busy schedule at Studio One, Ranglin still found time to work for other producers. Owing to contractual ties to Federal and other studios, he often had to do this on the sly.

He became the first person to play electric bass – rather than the more standard, at the time, double bass – on sessions for Prince Buster, thus setting the stage for future Jamaican bass guitar greats like Aston “Family Man” Barrett, Errol “Flabba” Holt and Robbie Shakespeare. On these moonlighting gigs, he sometimes strove to sound as little like Ernest Ranglin as possible, and of course to suffer the suppression of his name in the credits.

“Many times I had to disguise my playing,” he recalled. “I had to try not to let people, like Federal, know that I am playing. Even certain times when I used to play for Coxsone, my name was El Pancho. Most of the times, when I was at Federal, they didn’t want me to play too much guitar on people’s tunes. So I had to be a bass player. And whenever I had to do the ska on guitar, I could only ska [ie, play rhythm]. I couldn’t play solos, because I was restricted by Federal records.”

Despite this prodigious and sometimes thankless workload, Ranglin was hardly becoming a rich man. “Oh well, the pay was not even good to mention,” he laughed darkly when I raised the topic of money. “Those are sad memories when it comes to pay.”

Perhaps this is why Ranglin accepted Chris Blackwell’s offer to go to London in 1964 and work as an arranger for Island Records there, bequeathing his seat in the Skatalites to his guitar student Jah Jerry Hines. At the time, many Jamaicans and other West Indians were migrating to England – a cultural phenomenon recently depicted by filmmaker Steve McQueen in his Small Axe series for Netflix.

Ska was “hotting up” as the music of London’s West Indian youth community, and also catching on with the primarily white mod culture then coming to the fore. Even the Beatles imported a touch of bluebeat – as ska was also known – into the middle-eight guitar solo on their 1964 track I Call Your Name.

Ranglin became the arranger and guitarist on the first worldwide ska hit, Jamaican singer Millie Small’s version of the American R&B song My Boy Lollipop. It was the first time ska was heard in the United States and many other places. The record would go on to sell some seven million copies.

“One of the amazing things about it, Ranglin recalled, “was that the only Jamaican musician on that recording, apart from myself, was a trumpeter named Pete Peterson. Everybody else was from England or wherever on that side [i.e., Europe]. And they didn’t know anything about this music. But if you can read music, you don’t need a whole lot of explanation – as long as you’re a good musician. It was a little awkward for the pianist, I would say. But everybody seemed to fall in line.”

During the 10 months he spent in London, Ranglin also worked with jazz artists Cannonball Adderley and became a regular at the city’s top jazz club, Ronnie Scott’s, where he reportedly impressed the likes of Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton and John McLaughlin.

It’s tempting to speculate where Ranglin’s career might have gone had he stayed in England longer. But he had to return to Jamaica to be with his two young sons. “I guess this was a big sacrifice in my life,” he told me. “But I had to do that because, after all, your children come first.”

On his return to Jamaica, Ranglin discovered that ska had started to give way to the slower cadences of rock steady, which would eventually transform into the deep, heavy pulse of reggae. He made his mark in these genres as well. In fact some of his greatest work dates from this period.

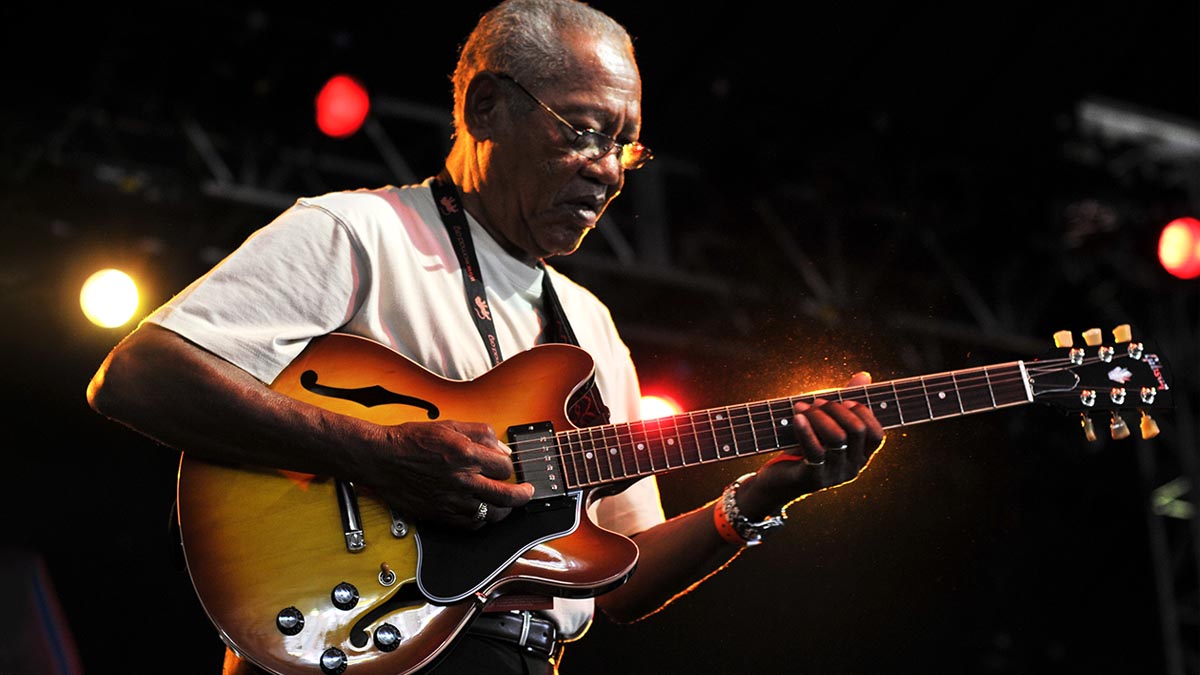

Ranglin’s chunky, palm muted, low-string riffs, played on archtop Gibsons for the most part, are the engine that drives classics like the Ethiopians’ Train to Skaville (1967), Toots and the Maytals 54-46 That’s My Number (1968) and the Melodians’ Rivers of Babylon (1970). These are some of the foundation “riddims” of Jamaica’s musical heritage – sampled, remixed and revoiced by countless artists in the years since then.

As reggae became a massive worldwide phenomenon in the Seventies, Ranglin continued to work with some of the genre’s foremost artists, including Jimmy Cliff, the Gladiators and the Congos. But he also began to devote more time and energy to jazz, gigging and recording often with Jamaican pianist Monty Alexander.

In 1996, Ranglin’s album Below the Bassline became the debut release on Chris Blackwell’s then-new Island Jamaica Jazz label. In recent years, Ranglin has been awarded an honorary doctorate in music from the University of the West Indies and was inducted into the Jamaican Music Hall of Fame. In 2016, he announced his retirement, leading an ensemble comprised of top players from Nigeria, Senegal, England and the U.S. on a farewell tour.

Many times I had to disguise my playing. I had to try not to let people, like Federal, know that I am playing. Even certain times when I used to play for Coxsone, my name was El Pancho

When I spoke with Ranglin in ’97, we were in the midst of another ska revival, with young bands like the Slackers, Hep Cat and Buck-O-Nine wowing Warped Tour audiences. I asked him what he thought of this latest iteration of this timeless Jamaican rhythm. His response was enthusiastic.

He’d just recorded a cover of Honky Tonk by his boyhood hero Bill Doggett with L.A. ska revivalists Jump With Joey for the 1997 Ska Island album. “It’s good to know that ska is coming back,” he said. “I notice a lot of artists from those old days are coming into prominence again. So it’s nice. But really I would love to push the music a little further. This is my aim.”

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.