“Mick came in with his Les Paul, plugged in to my amp and fiddled with the controls. All of a sudden there it was, the full Ziggy Stardust tone”: The post-Bowie career of Mick Ronson, rock ’n’ roll’s most quietly spoken guitar hero

Sure, he made a massive imprint on David Bowie’s classic early ’70s albums. But Mick Ronson also worked with Lou Reed, Bob Dylan, John Mellencamp, Elton John, Roger McGuinn, Morrissey, Ian Hunter and many others

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Although forever linked to David Bowie’s breakthrough success – and what is, for many, Bowie’s golden era in the early ’70s – Mick Ronson’s career continued long after his departure from Bowie’s band, the Spiders from Mars.

Bowie’s announcement from the stage of the London Hammersmith Odeon in 1973, when he unexpectedly declared that the Spiders had played their final show together, came as a huge shock to the rest of the band.

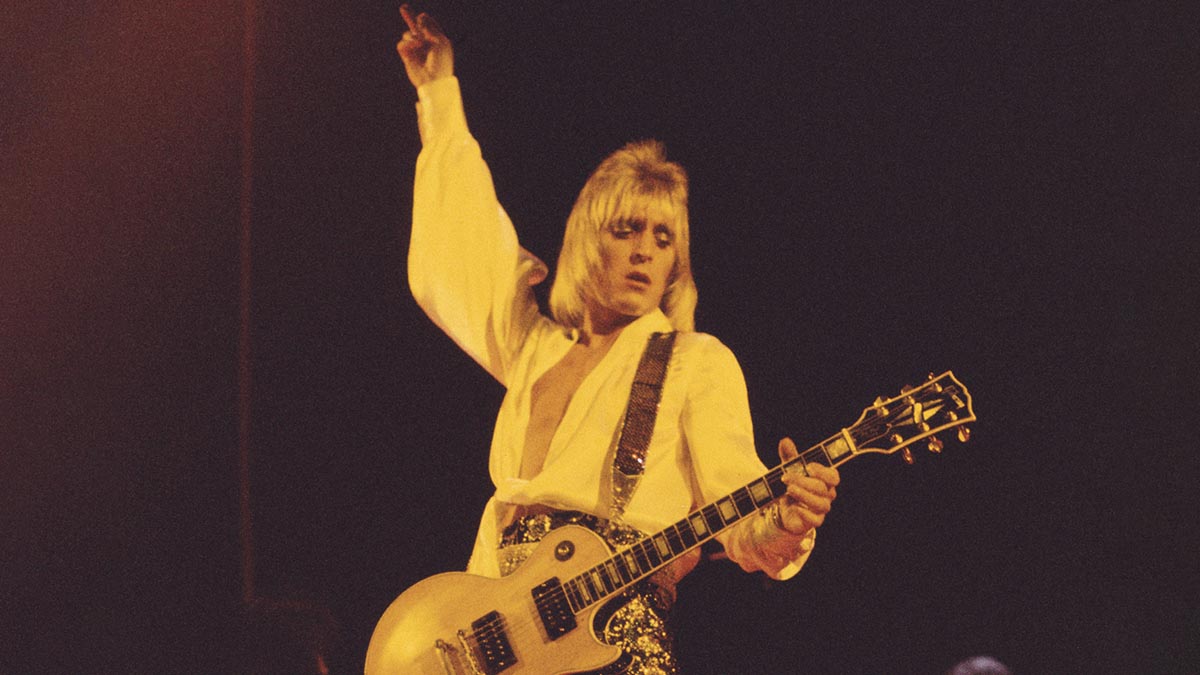

Ronson had carved out a reputation for himself as not only one of the premier guitar heroes of the glam age, but also as a gifted producer and arranger. While the band were understandably dismayed and disappointed at Bowie’s decision, plans were afoot to turn Ronson into a solo star in his own right.

Unfortunately for Ronson, he never seemed as comfortable in the spotlight as he was when acting as a visual and sonic foil for the extravagance of Bowie.

Ronson’s first band, the Rats, were a blues/rock band who made a handful of singles in the late ’60s. Hailing from Hull, in the northeast of England, the band undoubtedly suffered from being based outside the extremely London-centric scene that was the British music business at that time.

The Rats were an excellent band, with a sound not unlike that of the Jeff Beck Group, and Ronno could carry off the extended blues soloing that was becoming de rigueur in the age of Jimi Hendrix et al. with considerable aplomb.

Ronson’s playing was a cut above the clichéd blues rock excesses that so many mediocre Hendrix wannabes resorted to. Check out the Rats’ Telephone Blues from 1969 – no wonder that Bowie told Tony Visconti that he’d “found his Jeff Beck” when Ronson was recruited for Bowie’s band in 1970.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

A month after formally joining the Hype, the original name for Bowie’s backing band, Ronson played on Elton John’s Madman Across the Water as part of the Tumbleweed Connection sessions. The song didn’t make the cut for that album, but a re-recorded version became the title track of John’s next album. The Ronson version of the song didn’t turn up until 1992 on a compilation of Elton’s rarities.

It’s difficult to understand why Ronson’s version wasn’t used at the time; his blues-laden lines punch home with attack and verve – utterly dominating the song. Perhaps that is the reason his version stayed in the vaults, as Ronson completely overshadows Elton John’s performance.

While Ronson was primarily occupied with Bowie’s touring and recording cycle as he made his most iconic albums, he also was working as a producer and arranger – on his own and in tandem with Bowie. Ronson’s most famous co-production was his work on Lou Reed’s Transformer in 1972, on which he added guitar and piano to Perfect Day and Satellite of Love.

He added his arranging skills to Mott the Hoople’s All the Young Dudes the same year; he also struck up a friendship with Mott singer Ian Hunter that was to endure for the rest of his short life.

With the departure from Bowie a done deal, Ronson began to put together ideas for his debut solo album, Slaughter on 10th Avenue, which was released in 1974.

There was a lot riding on the record, and a major British tour was booked to promote it. The album received a mixed response. Listening to it now, it stands up well in its own right, although, unsurprisingly, the influence of Bowie seems to permeate the record. Ronson’s voice was up to the job of fronting a band, but he seemed to be moving outside his comfort zone in the live shows, where the focus was entirely on him.

The record contained a mixture of originals and covers; Ronno’s take on Love Me Tender saw him enter the U.K. singles chart, and the album achieved respectable sales figures.

According to Mike Garson, whose unique piano stylings featured on Bowie’s final Ziggy Stardust tour and the Aladdin Sane album, and who was a member of Ronson’s live band, attendances were poor for many of the shows. Many who did turn up were hoping Bowie might put in an appearance – a disheartening experience for Ronson.

Bowie’s management company, Mainman, still felt there was potential for Ronson to crack the big leagues as a solo act, and he was tasked with putting together a follow-up album, Play Don’t Worry, for release in 1975.

Prior to the release of his second album, he joined Mott the Hoople just before the band fell apart, to play on their final single, Saturday Gigs. While Mott were about to dissolve, Ian Hunter knew he’d found an ideal partner in Ronson – as a musical ally and a friend. Hunter was planning a solo career and wanted Ronson onboard.

The disappointing sales and critical response to Play Don’t Worry were, perhaps, the clincher in Ronson deciding to put aside plans for a solo career. Although the record moved away from a dependence on Bowie, it was still mainly comprised of covers, from Little Richard’s The Girl Can’t Help It to the Velvet Underground’s White Light/White Heat, although that song actually utilized an unused backing track from Bowie’s Pin Ups sessions.

The Ronson-penned single from the album, Billy Porter, received plenty of airplay but failed to make a dent in the charts, while the album just scraped into the top 30.

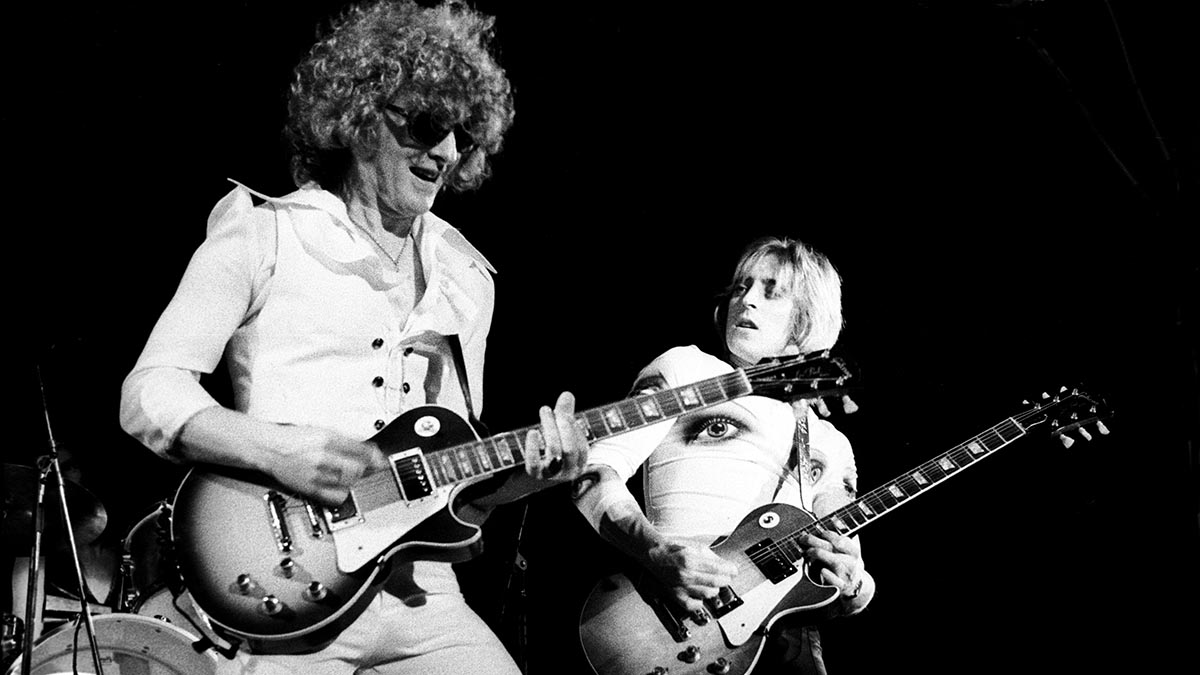

With solo aspirations on hold, Ronson threw his energies into co-producing and playing guitar on Hunter’s self-titled solo album in 1975. Although Ronson only co-wrote one of the songs, his influence is all over the album, which features some of his most blazing solos since his best work with Bowie.

Once Bitten, Twice Shy was a particular highlight, with an epic Ronno solo, scoring Hunter his last hit single and becoming a staple of his live set ever since. Def Leppard’s Joe Elliott was a lifelong fan and eventually became friends with Ronson in 1980. “For me, Ronno’s solo on that song is one of the greatest solos of all time, no question,” Elliott says.

With the pressure off, Ronson was free to do what he did best, which was (ironically) the title of his last album, Play Don’t Worry. Hunter remembers Ronson channeling a lot of his frustrations with the way things had been going career-wise into his playing, particularly the solo on The Truth, the Whole Truth, Nuthin’ But the Truth.

Ronson’s guitar work mixes delayed lines, manic wah tones and a devastating vibrato to deliver a performance of almost psychotic intensity. Blues-fired runs cascade and crash, but never descend into sloppiness, thanks to Ronson’s impeccably clean picking technique.

Says Elliott: “I played that on the tour bus a few years back, and Viv [Campbell] had to stop what he was doing and just sit back and listen with his eyes shut. He’d never been a particularly big Ronson fan until then, but the intensity of that solo was just insane.” Given the artistic and commercial success of the album, surprisingly, Hunter and Ronson didn’t work together again until 1979.

Ronson joined Bob Dylan’s live band for the Hard Rain tour in 1976, which came as a surprise to his friends, Since he’d never been much of a Dylan fan. The hard truth of Ronson’s situation was that, in spite of his high profile and reputation, he had never really earned the kind of money he should have received.

He wasn’t particularly well paid during his time with Bowie and needed to keep working to maintain financial stability. The Dylan gig was a welcome payday, although Ronson would never prioritize a lucrative deal over something that offered greater artistic considerations. Ronson actually received less than £50 per day (about $120 in 1972) for his work on Lou Reed’s Transformer, with no further royalties payable.

Alongside Ronson’s work with Dylan in 1976, he played on and produced former Byrd Roger McGuinn’s solo album, Cardiff Rose. A stylistically diverse collection of songs – from folk to upbeat pop/rock – it’s a record McGuinn has often cited as one of his favorites from his catalog. Ronson and McGuinn had both been part of Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue, and the album featured several other members from the live show.

Ronson’s background may have been hard-edged blues and rock, but he’d demonstrated his ability to cross stylistic barriers on his two solo albums. McGuinn recorded a version of Bowie’s Soul Love for the album, although it only turned up many years later on an expanded edition of Cardiff Rose.

Ronson may have embraced the role of sideman after the relatively disappointing response to his first two albums, but he continued to record his own material, with an eye on a third record. He recorded a full album’s worth of songs at the end of 1976, although the project only saw an official release in 1999, under the title Just Like This.

RCA refused to release it at the time, as they had lost faith with Ronno’s ability to sell records. Ironically, this would have been his strongest, most consistent album. With Ronson one of the few names from the pre-punk age not subjected to the year zero excoriation of all that had gone before, he could have capitalized on his cult hero status, had the album seen the light of day.

The title track is a punchy rocker, with a sound that seemed in step with the burgeoning punk/new wave scene that exploded while he was working on the album.

Given the U.K. punk scene’s enduring love of the work of Bowie and Ronson, it is unsurprising that Ronno was asked to play on and/or produce records for a number of the first wave of British bands.

Slaughter and the Dogs, who were one of the very first handful of punk bands to release a record, were such massive fans that they actually took their name from Ronson’s Slaughter on 10th Avenue album and Bowie’s Diamond Dogs.

Slaughter and the Dogs guitarist Mick Rossi managed to track down Ronson and struck up a friendship with him. When they signed to U.K. label Decca, they invited Ronson to the sessions for their debut album, Do It Dog Style, in 1978.

Rossi remembers: “Mick was such a friendly guy. I was only 15 when I went with a friend to see him on his solo tour in 1975. It was in Sheffield, and we lived in Manchester, which meant we’d have to spend the night after the show sleeping in the bus station. We were only 14. We managed to meet Mick on his tour bus after the gig.

Mick came in with his Les Paul, plugged in to my amp and fiddled with the controls for a moment. All of a sudden there it was, the full Ziggy Stardust tone

Mick Rossi

“When he realized we had nowhere to stay, he paid for a hotel room for us where the band were staying. He even gave me his phone number and said to keep in touch, which I did, and that was how I managed to get him to play on our album.”

Rossi remembers a particularly magical moment in the studio during the day Ronson spent adding his guitar to a couple of the tracks. “I’d bought a Marshall stack and I had a Les Paul, but I was just turning everything up to the max. The sound wasn’t really working. Mick came in with his Les Paul, plugged in to my amp and fiddled with the controls for a moment. All of a sudden there it was, the full Ziggy Stardust tone. It was just incredible.”

Glen Matlock, who first came to prominence in the Sex Pistols, asked Ronson to produce Ghosts of Princes in Towers, the debut album for his band Rich Kids, released in 1978, after he left the Pistols. As with everybody who worked with Ronson, he was bowled over by his complete lack of pretension and incredible friendliness.

Typically of Ronson, who never really seemed to refuse any request to work with him, Matlock had answered a phone call in his manager’s office, realized it was Ronson he was speaking to and invited him to come to their rehearsals at the spur of the moment. While Ronson didn’t play guitar on the record, he played keyboards on a few songs and added a creative spark to the sessions to help Rich Kids deliver an underrated new wave classic.

By 1979, Ian Hunter had recruited Ronson again to produce and play on You’re Never Alone with a Schizophrenic. Hunter acknowledged the importance of Mick, stating that nobody could ever play his songs the way Ronson did. Hunter continued to rely on Ronson’s production and guitar skills for the next three years, recording Welcome to the Club in 1980 and Short Back ’n’ Sides the following year.

Ronson toured extensively with Hunter, being given full rein to unleash the best soloing of his career. YouTube is full of performances showing the intuitive level of rapport that Hunter and Ronson enjoyed, delivering live versions of classics that actually blow the original recordings out of the water.

During his extended run with Hunter, Ronson had recorded a number of tracks for a project that was mooted as a soundtrack for a film that didn’t actually get made. The album later turned up as Indian Summer in 2001. The majority of the songs were recorded in 1981, with several being cut the following year.

Ronson’s frustration with his solo work must have been exacerbated by this latest failure to get one of his own projects off the ground, following RCA’s refusal to release Just Like This a few years earlier. Ronson’s contribution to Hunter’s 1983 album, All the Good Ones Are Taken, was minimal as Ronno was seriously considering dropping out of the music business altogether – unsurprising given how frustrating it must have been to have been unable to find recognition for his own projects.

Mick Rossi had maintained his friendship with Ronson. He remembers that Ronson never really complained about anything, always maintaining an upbeat, positive vibe. “I think perhaps, given that Mick knew how much I looked up to him, he didn’t ever want to come across as negative,” Rossi says. “I’ve heard from others that he did feel that things weren’t all they should be, but he never really seemed to dwell on the downside of things.”

The previous year, 1982, had seen Ronson’s arranging skills hit paydirt for John Mellencamp, who’d been struggling to record his breakthrough hit, Jack and Diane, while still performing as John Cougar.

Ronson was working on the session as a guitarist and came up with the big choir-style hook in the middle of the song. It was a lightbulb moment for the session, and a song that was in danger of being junked became transformed into a global hit.

Ronson also produced the first of two albums, No Stranger to Danger, for Payolas, a Canadian band notable for their inclusion of future mega-producer Bob Rock among their ranks, playing bass. He produced Hammer on a Drum for them the following year. No doubt Rock picked up plenty of tips that would stand him in good stead as he went on to become one of the most in-demand producers from the ’90s onwards.

Ronson decided against dropping out and was energized by watching a performance by Lisa Dal Bello in 1983. He contacted her and they teamed up to work on her fourth album, Whomanfoursays, which she recorded under the name Dalbello. Ronson and Dalbello produced the album together, and all instruments were played by the pair.

Elliott remembers going to see Ronson playing in a pub venue in London with Dalbello: “The place was full of Ronson fans. A lot of people there were in other name bands, guys who’d always loved Mick’s work.”

At the time Ronson became involved with the Dalbello project, he had been offered the chance to produce Tina Turner, but was unable to follow through, missing out on what would have been his most lucrative job to date. The oft-reported tale that Ronno always prioritized artistic interest over commerce was proven true yet again.

Although there was little happening on the recording front, Ronson decided to return to live work in 1985, touring with Ian Hunter and also fronting his own band, continuing to tour regularly with Hunter throughout the remainder of the ’80s.

Given the longevity of the relationship of Ronson and Hunter, it seemed long overdue when they announced that they planned to record as the Hunter Ronson Band, with their first album, YUI Orta, appearing late in 1989.

One of the strongest albums in either artist’s catalog, surprisingly, it didn’t sell as well as expected, and although a follow-up was planned, that fell by the wayside once Ronson’s health started to fail.

Billy Duffy remembers buying tickets for a scheduled Hunter Ronson show: “It got canceled – I couldn’t believe it. I was so disappointed. I even managed to get the poster advertising the show, which I’ve got on my website. What a brilliant band that was.”

Elliott is convinced that the combo of Hunter and Ronson brought out the very best in both of them. “The work Ian did with Mick is just fantastic,” he says. “That was a gift that Mick had, the ability to bring out the very best in anyone he worked with.”

In 1991, Ronson received the diagnosis that he had liver cancer, and that it was inoperable. According to friends, he seemed to be able to remain relatively upbeat in the face of such devastating news. In 1992 he was asked by Morrissey to produce Your Arsenal. Given Ronno’s tricky financial situation, the timing was perfect as it provided him with the biggest payday of his career, relieving a huge amount of strain.

Ronson made his final live appearance at the Freddie Mercury tribute show, at Bowie’s suggestion, playing All the Young Dudes with Hunter on vocals. That was followed by a deeply moving version of Heroes, made all the more poignant in hindsight with the knowledge that it was to be Ronno’s last show. Elliott remembers, “To be standing on the stage with Phil [Collen], doing backing vocals, with Brian May next to us, then looking across at Mick, Bowie playing sax and Ian Hunter singing, backed by the rest of Queen – there is nothing that could ever top that.”

Ronson’s last appearance on record was on My Baby Is a Headfuck by the Wildhearts, where he unleashes an explosive slide solo. He had been working on his final solo album, eventually to be released in 1994 under the title Heaven and Hull but was unable to complete it, before he succumbed to cancer in April 1993. Ian Hunter, David Bowie, John Mellencamp and Joe Elliott stepped in to add vocals and help complete the record.

For many, Bowie’s best work was created in tandem with Ronson. Likewise, few could argue that Ronno took Ian Hunter to new heights. Ronson was the perfect combination of artistic ability and iconic imagery, the definition of everything a guitar hero should be. His influence stretched far beyond the time when he was Bowie’s ultimate sonic and visual counterpart.

Randy Rhoads lifted Ronson’s image wholesale, and even emulated his “Les Paul into a Marshall with a cocked wah” sound. Michael Schenker admitted to basing much of his tonal approach on Ronson’s sound. Billy Duffy remembers watching Ronson on Top of the Pops and realizing that was what he wanted to do. Joe Elliott and Phil Collen have endlessly waved the flag for Ronson’s remarkable abilities.

Perhaps the most telling example of Ronson’s abilities lies in a short YouTube clip filmed not long before his death for a BBC documentary.

He’s playing the blue Tele that he favored in later years, into a small practice amp – worlds away from his signature gear choices of a Les Paul and a Marshall stack, yet the sound produced is so unmistakably that of the Ziggy era, that the oft-stated notion that a person’s sound is all in their hands, seems to be proven once and for all.

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.