“Everyone else had walls of Marshalls, but Rory just turned up, put a Vox AC30 on two folded-out chairs and let rip”: Rory Gallagher – the gear behind the legend

As we rebuild the exact rigs from the late Irishman’s most famous live periods, using historic gear loaned by his estate, Daniel Gallagher looks back over his uncle’s lifetime onstage

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

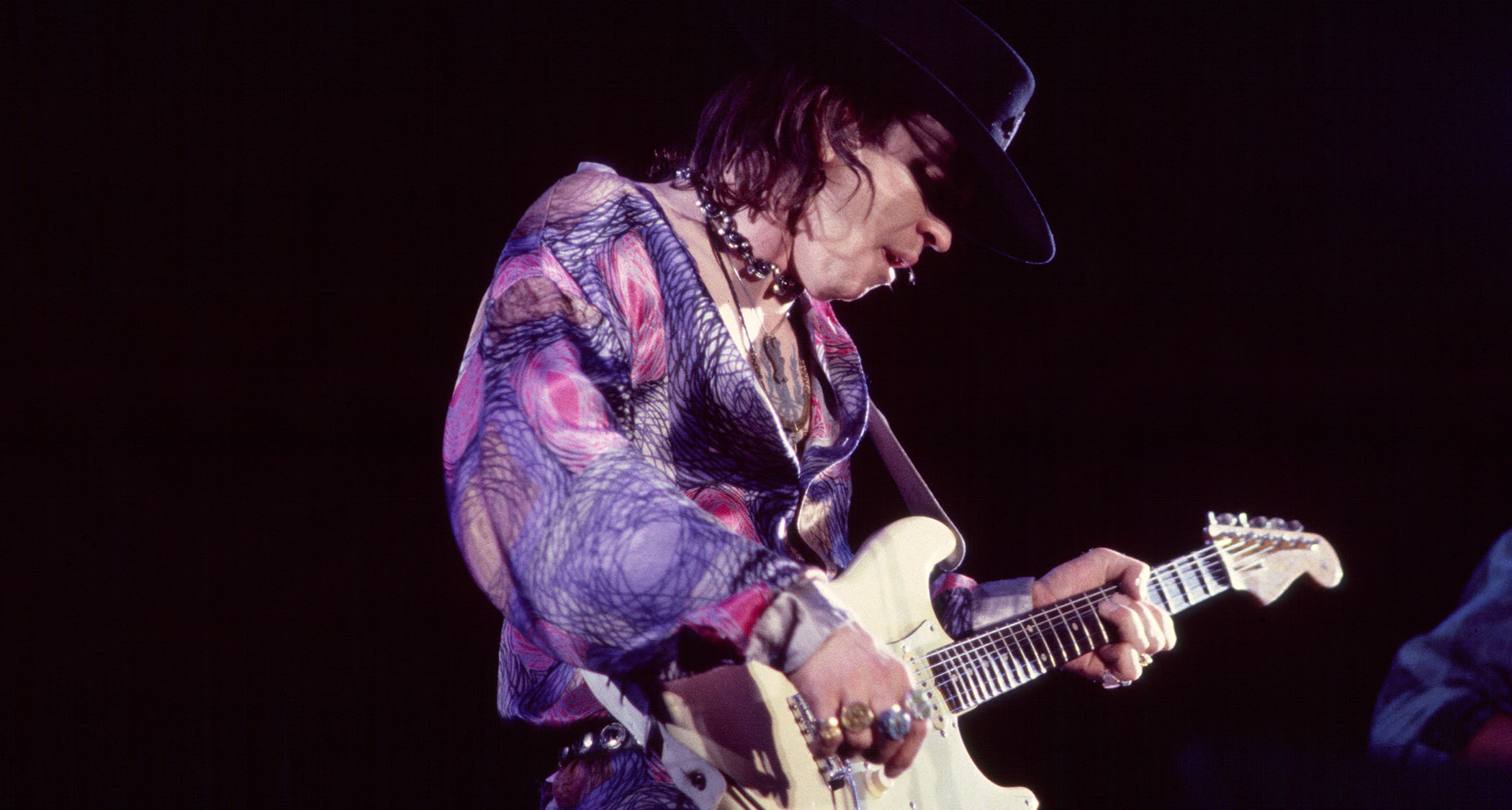

You only had to glance at Rory Gallagher to know the road was his natural habitat. The rumpled check shirt, the three-day stubble, the air of nomadic bliss: everything suggested a twilight creature to be spotted at the stage door, gas station and bolthole motel.

As Joe Bonamassa once told this writer: “Rory was the guy who would pour out of the van after he drove for 17 hours, set up his own amp, plug in, play the best show you’d ever seen in your life, pick up his amp and guitar, get back in the van and drive to the next city.”

As Rory’s nephew – and the producer of his posthumous releases, including All Around Man, a new cut‑and-shut of two fierce London shows played in December 1990 – Daniel Gallagher knows better than most what it meant to his uncle to take the stage.

And as he unboxes the fabled guitars, amps and pedals that have largely lain dormant since Rory passed in June 1995, Daniel recalls the startling gearshift from the gentle, shaggy-haired relative to the febrile showman flaying the last of the paint from his ’61 Stratocaster.

“I think that Rory came alive on stage, or certainly that alter ego he had. He was such a shy, quiet guy but then he became this animal. I knew him well as a kid, and I remember seeing him live for the first time at the Hammersmith Odeon in ’87. My dad pulled back the curtain at the side of the stage, Rory was already playing and I remember thinking, ‘That’s him?’ It was surreal knowing him from playing football in the back garden to this guy machine-gunning the crowd and going crazy.”

If the road suited Rory’s temperament – “It’s my reason for living,” he once said – it also brought out his best as a player. Certainly, there is abundant gold in Gallagher’s 11-strong studio catalogue. But the impression endures that this restless road warrior viewed the studio as merely an echo of the intensity of live gigs.

As mid-’70s keyboard player Lou Martin once noted: “Rory wasn’t at his most comfortable or happiest in the studio. If he didn’t have somebody to look at then he couldn’t feed off the energy.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

There’s no doubt Gallagher tapped his mojo most readily on the boards. Even if you never saw him live, the evidence is there on 1972’s Live In Europe, Irish Tour ’74 and 1980’s Stage Struck: all three widely viewed as some of the best live albums ever.

“Rory’s passion was always seen on stage more,” says Daniel. “I remember Johnny Marr saying he was scared of him, the first time he saw Rory live, because he was so aggressive. People say that in the audience at a Rory concert, especially in the ’70s, you got so caught up with how much he put into it that you ended up sweating bucketloads as well.”

Gallagher’s Gear

Unless you knew better, you might imagine Rory’s instrument and backline choices would be as relaxed as his wardrobe and demeanour, that he would plug in whatever was to hand and make it sing.

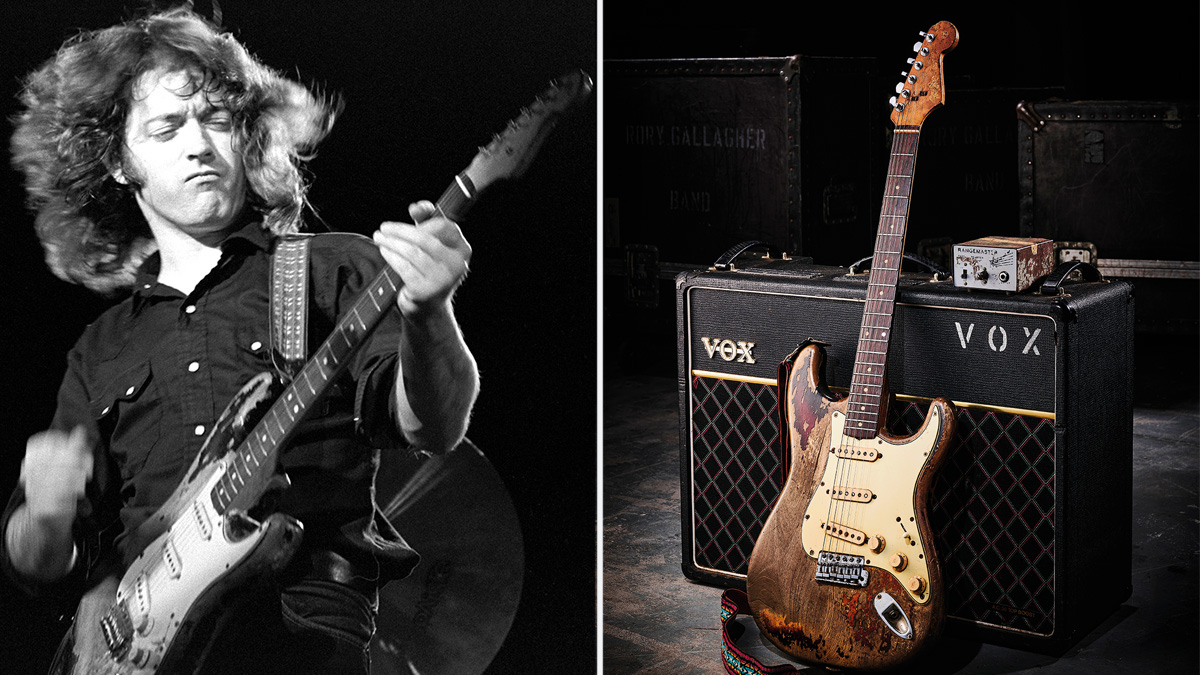

But that notion evaporates as Daniel unloads the late guitarist’s historic gear in the Guitarist photo studio, assembling the disparate rigs that reflect the evolving musical direction, personnel and circumstances of Rory’s three-decade career.

Formed in Cork in late ’66, but making their mark after moving to Belfast a year later, Rory’s first serious band, Taste, was a fiery power-trio whose combustible telepathy rivalled Cream. Yet in this early period, the guitarist clung to the gear of his teen apprenticeship on Ireland’s showband circuit.

He was already wedded to the ’61 Stratocaster – reputedly one of the first to arrive on Irish shores – that would become his closest thing to a calling card. “It was very easy to play from the start – it has a very flat kind of neck – and I’ve kept it ever since,” he said. As for the beat-to-hell aesthetic, Rory shrugged: “There’s a theory that the less paint on a guitar, the better.”

Daniel picks up the story: “He’d had a Rosetti Solid 7 and a no-name amp before that, but when he joined the Fontana showband at 15, they had a Vox AC30 and as soon as he plugged in his Strat, there was a love affair there – that would carry on to him starting Taste. He still had the AC30 with the Strat and then, in about ’67, he came across the Dallas Rangemaster Treble Booster, which he ran into the Vox’s Normal Channel.

From ’68 – the second iteration of Taste – that’s when you really hear that combination. Taste were ferocious live, and how hard and high he ran the amp and the signal into the amp gave him that incredible tone. He’d have the amp all the way up then control the volume via the guitar. And the booster really made it scream.”

Arguably, the finest example of that holy trinity is Taste’s casually brilliant set at the 1970 Isle Of Wight Festival. “Everyone else had walls of Marshalls, but Rory just turned up, put a Vox AC30 on two folded-out chairs and let rip,” shares Daniel in disbelief. “It’s a hell of a sound.”

In Bad Taste…

Critically revered but living in penury due to bad management, Taste were nearing the end as they crossed the English Channel. The band’s sour split left its scars on Rory – he would never revisit Taste’s material live – but his backline was too good to dismiss.

“He stuck with that sound through his first two solo records and 1972’s Live In Europe,” explains Daniel. “Rory’s first solo album [Rory Gallagher] had Wilgar Campbell on drums and Gerry McAvoy on bass, and it was almost jazzy. Even when they were loud, they went off in places and Rory’s guitar runs are quite jazzy and he has quite a clean tone.”

Following that solo breakout, there’s an argument that the best year to watch Rory Gallagher live was 1974, as he returned to Troubles-torn Belfast for the incendiary shows that would be cherry-picked for the deathless Irish Tour ’74 album. At a time when most stars avoided Northern Ireland, Gallagher earned added kudos among his countrymen by lodging at The Europa, which enjoyed the dubious accolade of the world’s most bombed hotel.

“Irish Tour ’74 is hard to beat,” says Daniel. “I always found his cover of Tony Joe White’s As The Crow Flies a magical moment. You get this audience hush because he’s just playing his National guitar.”

“I always found his cover of Tony Joe White’s As The Crow Flies a magical moment. You get this audience hush because he’s just playing his National guitar

At those rabble-rousing shows, eagle-eyed fans noticed changes afoot. “In about ’73, Rory had brought in a keyboard player [Lou Martin] and a new drummer [Rod De’ath]. I think he’d had to find his new place in the EQ spectrum. Maybe the ferocity of the Rangemaster and AC30 wasn’t fitting in with the piano, so he added a Fender Twin, which gave him a rounder sound. And then, going into 1975’s Against The Grain, that line-up got quite funky. He adds in soul covers like I Take What I Want, and I think the Fender fitted that.”

Around the same period, the gloriously battered Fender Bassman you see here entered the frame. “He fell in love with that amp and started going to the Bassman and Twin together,” says Daniel. “When Rory went on big US tours opening for Deep Purple and the Faces, they were playing stadiums. That might have been another reason to go for two 4x10 Fenders together, because the Vox wasn’t going to do it at Madison Square Garden, y’know?”

By the late ’70s – another unmissable period caught on 2020’s posthumous Check Shirt Wizard release – Rory had alighted on a third Fender combo. “He’d come across the Concert,” says Daniel. “So in about ’77 he’d start linking the Bassman and Concert with a Hawk II booster, which had that graphic-equalising effect. In the studio, he’d even drive the hell out of small Fender Champs, but on stage, it needed to be a 4x10. The two Fenders together did that for him for a good while.”

In the studio, he’d even drive the hell out of small Fender Champs, but on stage, it needed to be a 4x10

It was Rory’s growing heaviosity at the turn of the decade – summed up by 1980’s Stage Struck – that demanded a rethink. “Getting into that harder rock period of Photo-Finish [1978] and Top Priority [1979], Rory started messing around with Ampeg VTs. Then, by Stage Struck, he had two Marshall 50-watt JMP combos hooked together with this Boss DB-5 pedal that he used as an equaliser, pushing the mids on the two amps.

“It was a ferociously loud band, with Ted McKenna, who was Rory’s hardest-hitting drummer. So maybe his thinking was, ‘This is my big tone for this hard‑rock period.’ He’d always played pinch harmonics, but the squeals he gets on Stage Struck are very particular from how hard he’s pushing those Marshalls.”

The Last Decade

The received wisdom is that Gallagher was past his peak by the early ’90s, but that’s refuted by the stinging tracks on All Around Man: Live In London.

“There was nothing written on the tapes,” reflects Daniel of initiating the project, “but I could hear the songs were from Fresh Evidence [1990] and Defender [1987]. Then he calls out in the second song – ‘Great to be here at the Town & Country!’ – which is now the O2 Forum [Kentish Town].

“There’s always trepidation,” he admits. “You don’t think of Rory having bad gigs, but could it be one of those? But it’s just phenomenal. The line-up is Gerry on bass, Brendan O’Neill on drums, Geraint Watkins on accordion and Mark Feltham on harmonica, and they’re absolutely flying.

Rory, at this point, is almost more groove-based. On Heaven’s Gate and Continental Op, his playing is lot more in the pocket. There’s an eight-minute version of Ghost Blues, really killer rhythmic stuff. Almost like Billy Gibbons: a very earthy style of playing, compared with the ’71 stuff. At one point he does these volume swells in Moonchild and it’s jaw‑dropping.”

For his last stand, Rory came full circle – with a twist. “He said once that the Vox was his favourite amp, hence starting out with it and bringing it back at the end,” reflects Daniel. “It was always there in the back of his mind, even when he was cheating on it with the Fenders! On the Vox, he had a slapback using an analogue delay, so that would be the Memory Man or DOD 680.

“For these London shows,” continues Daniel, “he’d gone for the Marshall into the Vox, into a Marshall stack. But it’s funny because having always been known for playing through combos, he didn’t want to go, ‘Well, now I’m the stack guy.’ So he covered up the 412 speaker cabinet and just showed the head of that Super Bass, which was converted to be more of a Super Lead.

“Each of those three amps were mic’d up separately, so it was fun mixing them: the slapback echo on the Vox, the midrange’d Marshall 50-watt and the dirt from the Super Bass.”

By this point, Rory also had more underfoot. “The Boss octave pedal added colour to his solos and the Tube Screamer was to go even louder,” explains Daniel.

“For certain songs he’d add flanger: Shadow Play had those little touches, just for variety and mystique. He had the Dyna Comp on all the time in this period. And he still had the DB-5 into the Marshall. It’s funny how certain boxes ‘belonged’ to certain amps. Like, the Rangemaster belonged to the Vox; you don’t see him putting it into any of the Fenders.”

As we break and box the iconic backlines that changed the course of blues-rock, it’s hard to shake the hope that Rory would smile down to hear his rigs roar once again.

For the late Irishman, these careworn guitars and amps were the sound of the road, and for Rory Gallagher, the road was life. “I think it was his happiest place,” concludes Daniel. “I always got the feeling he was only himself for the two hours of every day he’d be on stage…”

- All Around Man: Live In London is out now via UMe.

- Guitarist would like to thank Rory Gallagher’s family and Michael Kelly for their kind and invaluable help in putting together this unique feature with Rory’s original gear.

Henry Yates is a freelance journalist who has written about music for titles including The Guardian, Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a talking head on Times Radio and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl and many more. As a guitarist with three decades' experience, he mostly plays a Fender Telecaster and Gibson Les Paul.