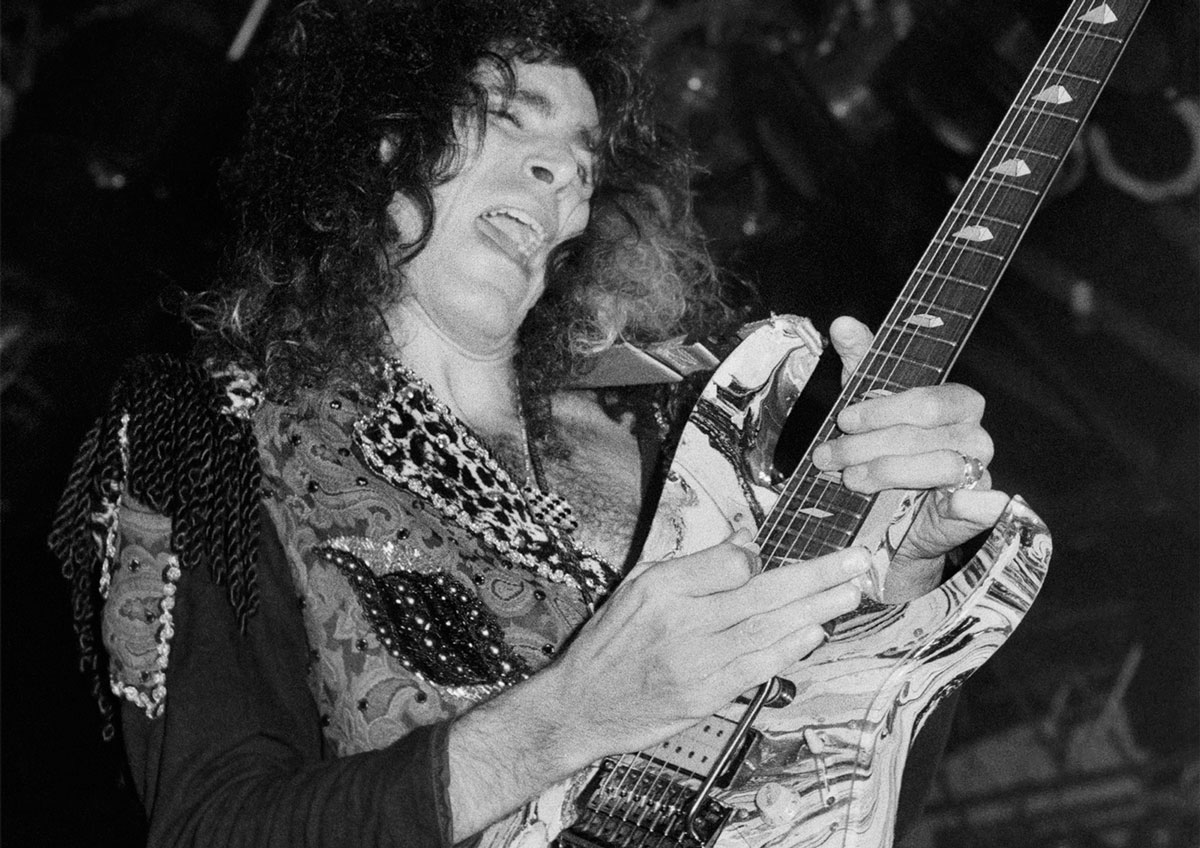

Steve Vai on his time in Whitesnake: "There was real aggression and control in my playing. I just remember thinking it was never good enough back then!"

Three decades after its release, Vai takes you inside the making of Whitesnake’s Slip of the Tongue, the album that sent the band into uncharted territory

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Steve Vai will be the first to tell you how uncanny his charmed life in rock ‘n’ roll has been. While his work as a game-changing guitar expressionist (and his hallowed discography of instrumental albums) might take priority in the minds of guitar fans, Vai’s odyssey through the ranks of rock music is the stuff of legend.

As a gifted teen, Vai travelled from bedroom woodshed to the bootcamp of Frank Zappa’s band, after which he took the reins from famously furious neo-classical shredder Yngwie Malmsteen in Alacatrazz. Vai left the Alcatrazz gig to join David Lee Roth in spearheading the singer’s wildly successful post-Van Halen solo group, a gig he left in 1989 only to have yet another coveted lead guitar role “fall in his lap” (as he tells it), this time with one of the biggest bands of the '80s: Whitesnake.

With Whitesnake, Vai did more than just enjoy a casual walk-on with a band at the peak of its success. He reshaped the group’s sound from the inside out with his contributions to 1989’s Slip of the Tongue.

That album marked a major shift away from the brand of muscular blues-rock Whitesnake was known for, chiefly due to Vai’s penchant for theatrical flash, flare for painting with effects and layered approach to tracking guitars. Slip of the Tongue brought Whitesnake’s sound into the future and, while it was an album that risked leaving fans behind, it would go platinum before the grunge revolution changed the face of guitar music altogether.

Oddly, despite Vai’s massive resume, he got the Whitesnake call because frontman David Coverdale was so impressed by his performance and guitar contributions to the 1986 film Crossroads in which the guitarist famously played the role of Jack Butler, the Devil’s shredder.

Slip of the Tongue celebrated its 30th anniversary late last year and was treated to a royal re-release package, complete with a fresh remaster and an expanded, deluxe edition of the album that boasts unreleased studio recordings, music videos, a new interview with Coverdale and a recording of the band’s positively blistering 1990 headlining set at Castle Donington.

In anticipation of the album’s big birthday, Guitar World was invited into Vai’s studio, the Harmony Hut, to chat about the album. The guitar hero opened up about his sole release with the band, lessons learned from Diamond Dave and his working relationship with Coverdale and co-guitarist Adrian Vandenberg. He also reflected on what was one of his finest moments as a bona fide rock star.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

David Coverdale had a lot of experience working with gifted players when you joined the fold and seems to be someone who really values the interplay between a frontman and a dazzling lead guitarist. What was he like to work with? Was he hands-on or did he get out of the way and let you do your thing?

"David was a prince! He had a lot of confidence in me and basically knew he needed to just let me do my thing. David knew what I was capable of and didn’t really interfere with what I wanted to do. I just did it, and if there was something he didn’t like I was happy to change it because it was his thing. Working with David was great and there was something in his phrasing as a singer that I just adored.

"There was really only one situation where David asked me to redo something and I completely agreed. It was on The Deeper the Love. I had done a solo using a piece of rack gear that was the hot new piece of gear at the time. I won’t mention who it was made by, but I hated the thing, but everybody was saying how great it was, so I gave it a spin.

"It sounded like shit - thin and buzzy like a deranged mosquito! I wasn’t really satisfied with the sound on the solo and, sure enough, David heard it and went, 'Steven darling, would you mind redoing this solo - it sounds a bit thin.' Other than that, he just let me run with it."

The lore goes that many of the guitar parts on Slip of the Tongue were already written by co-guitarist Adrian Vandenberg when you joined, but he had a recurring wrist injury flare-up and was unable to track the album. Is that correct?

"Not exactly. When I had joined Whitesnake, the tracks were already recorded and Adrian had laid down guide rhythm tracks. What had happened was Adrian developed this situation with his wrist that persisted throughout the tour. I’m not sure what caused it, but he’d have to soak his wrist after every show.

"Adrian’s such a great player, but the injury made it so he couldn’t really sustain for too long because of the pain. I’ve stayed pretty close with Adrian over the years and I see him whenever I’m in Holland, and when I spoke to him a couple of years ago he was still having that wrist problem - but they located the source of it to his neck.

"So Adrian had made these guide tracks and that were basically chords and structures, and I obviously copped a lot of the riffs from those, but I put my spin on them because it was all like one track of guitar. I went in with 20 tracks on some songs; it’s a very dense guitar record and I definitely did my best to decorate it! It was a departure for what Whitesnake was normally known for in the guitar department."

Did you have any reservations about not staying wholly true to Whitesnake’s old signature sound?

If I had tried to sound like Yngwie [Malmsteen] when I had joined Alcatrazz, it just wouldn’t have worked because I’m very satisfied with the way I play, but I also can’t play like Yngwie.

"You have to find a balance between what’s expected of you from the band, what the fans are expecting, what the song requires and is telling you to do - and also being true to your own voice. I had no choice but to express my own voice because that’s all I know!

"If I had tried to sound like Yngwie [Malmsteen] when I had joined Alcatrazz, it just wouldn’t have worked because I’m very satisfied with the way I play, but I also can’t play like Yngwie. It was the same thing when I was playing with Dave [David Lee] Roth; I needed to deliver in a rock context - which was very natural to me - but I’m not going to compete with Edward Van Halen!

"There’s no way those records would’ve been accepted if I didn’t have some kind of rock integrity, but I knew what the songs needed and I knew what the audience was expecting and there’s a side of me that I knew could deliver that. It was the same thing with Whitesnake.

"The foundation of Whitesnake’s sound was rooted in rock blues, and there’s a whole culture that emanated from Europe in that traditional solid rock blues guitar playing that had a real authenticity to it.

"Michael Schenker, Uli Jon Roth, Adrian Vandenberg, Ritchie Blackmore, Jimmy Page - that was the sound all Whitesnake records had been built upon. But Whitesnake had gone through different permutations of guitar sounds throughout the years, and the previous one to me was John Sykes, and he absolutely had his own sound.

"Sykes didn’t sound like any other previous Whitesnake guitarist, but his thumbprint is an indelible part of the Whitesnake record he did. The fatness of that record and the rock integrity it had was all Sykes. So I knew I wasn’t going to sound like Sykes and I wasn’t going to try to.

"You cheat yourself when you try to do that and play like someone else. And the audience is a lot smarter than you think; they’re very intuitive and perceptive and if you try to pull anything over on them - like biting someone else’s thing - you’ll get beat up for it."

What did you learn during the Roth years that you brought with you when you took the Whitesnake gig?

"When I joined Dave Roth, I was coming from Frank Zappa and Alcatrazz, so I had never really had the experience of being on a big rock arena stage. With David Lee Roth in the '80s, it didn’t really get any bigger than the rock ‘n’ roll we were doing, and there was an element of fun and even a quirkiness to it.

"I was perfectly suited to the Roth gig and I think that experience taught me how to translate what I do to a big audience - how to truly entertain in a rock band. With Frank [Zappa], you stood there and you made sure you’re playing the right notes. With David Lee Roth or Whitesnake, you have to entertain.

The image I created was this character that had almost effortless skill, wizard-like in their playing and very graceful in their movements

"Now, I’ve always liked theater and the over-the-top and I’m a total ham - I really love performing! In my mind’s eye when I was a kid, I’d lie in bed and listen to music and see myself performing - not just playing. I’d create a visual of myself doing the whole thing because when you’re a kid you’re allowed to think like that. There’s no taboo in being 11 years old with your headphones on making believe you’re playing in front of thousands and thousands of people and creating an image.

"The image I created was this character that had almost effortless skill, wizard-like in their playing and very graceful in their movements. I saw this very elegant movement to things and a specific integration between their playing and their movements. What I didn’t realize at the time is I was creating who I’d become.

"We all do it and don’t even realize we’re doing it, but whatever you’re thinking about and fantasizing about as a kid, you might become if you’re lucky and work hard."

Your iconic second solo record, Passion and Warfare, was happening around the same time you got the Whitesnake call - is that right?

"I had started recording Passion and Warfare before I had even joined Dave Roth’s band, and the release was scheduled before I knew I was going to join Whitesnake. It kind of coincided right when I was kicking off the Whitesnake tour."

It shows a pretty serious lack of ego to push a solo record that you had toiled over for that long to the back burner to tour with another band.

"The decision at the time came because I was always very comfortable with the idea of being the sideman and working with a really great lead singer. With Dave Roth, you had one of the best frontmen of all time and especially of the '80s.

"What Dave did - his command and the ego he brought to the stage - was theater and show and such an important part of what made rock ‘n’ roll what it was back then. However, when I was working on Passion and Warfare, I knew that all of these rock bands I was in were relatively fleeting and that the whole big rock-star thing had a certain shelf life.

That music said to me, 'You can do this rock star stuff and that’s OK, and you do it the best you possibly can, but I’m waiting for you'

"I’m so grateful that I was able to play around in that arena for a while; it really satisfied a lot of that urge to be a rock star and to explore that life. But, the more compelling movement in me was always - since before all of the bands and even before Frank [Zappa] - the music I was hearing in my head.

"As uncommercial or whatever you want to call it, that music was compelling and always calling to me, you know? That music said to me, 'You can do this rock star stuff and that’s OK, and you do it the best you possibly can, but I’m waiting for you.' I went to Capitol Records to deliver Passion and Warfare, and I had to tell them I had joined up with David Lee Roth and I couldn’t finish my own record and go on tour because the schedules conflicted.

"I’ll never forget what Joe Smith at Capitol said to me: 'Steve Vai, you are a shooting star that has no place to land,' meaning you’re just going to keep going and it’s OK that you’re doing this stuff now, but you will have to at some point do the music that’s inside of you because if you don’t you’re going to be miserable and there’s not enough money or fame that will be able to satisfy your creative instincts."

That’s an unexpectedly empathetic sentiment from a record exec at a major label in the 1980s!

"That was the gist of it, and what was interesting was when it came time to finally release the thing, I went back to Capitol, and Joe Smith wasn’t with the company any more. The guy that took over - Simon Potts - actually said to me, 'I don’t understand this record and I don’t know what to do with it. We’ll put it out, but we’re not going to do any promotion, and your advance of $250,000? We’re going to cut that in half.'

"Most musicians at the time would’ve been like, “Oh, you suck! But OK.” and I just said, “OK, great! Bye!” and I left and didn’t give them that record. They thought that I’d be fine with whatever they said, but I said no, paid back my advance and I shopped my record elsewhere."

Where were you at as a player when you got the Whitesnake call?

"It’s interesting because a couple years ago I saw a clip of one of the shows we did at Donington and I couldn’t believe it! I said, 'Is that what I played like back then?!' It was pretty fierce and there was a real aggression to it. And a lot of control. I just remember thinking it was never good enough back then.

There was a part of me back then that always went, 'Why are all these people reacting this way to the way I play? It’s not that great'

"I think that’s a common thing in some people: knowing that what you’re playing is the right thing and that it feels right, but always feeling like you could do better or do more. And then you get older and you look back and realize you were completely blind to how good you were.

"There was a part of me back then that always went, 'Why are all these people reacting this way to the way I play? It’s not that great,' because I always felt like there was another level! You don’t know that you can’t see the forest for the trees."

You tracked the guitar parts for Slip of the Tongue at your own recording studio. Do you recall your core signal path for the album?

"Tons of guitars made appearances, but the majority of the tracks were done with the first prototype of the Ibanez Universe seven-string. I got that guitar right before we started tracking that record, and that’s what I used for the main parts. You can really hear it there, but there’s also all sorts of decorations and auxiliary guitar parts that were done with a lot of different guitars.

"As far as the effects at the time, multi-effects were just coming out, so we were still stacking various rack-based choruses, delays and phase shifters. With the exception of the distortions and wah-wahs, everything was in rack units.

"There was a myriad of amps being used, but for the most part I was into Soldanos at the time - early SLO-100s. I also had some older modded non-master volume Marshalls that had been modified by Jose Arredondo who was the guy at the time and had done all of Edward Van Halen’s amps. I was introduced to him through the Roth camp and he did a bunch of amps for me. The Carvin amps were out of the picture at that point."

Could you give some examples of how and where you incorporated the extended range?

"It’s all over the record. It’s hard to hear because it’s not utilized the way contemporary seven-string players use it. Whenever there were low notes between B and E, I used them. The seven-string is really apparent on Slow Poke Music, Judgement Day and Kittens Got Claws.

"Obviously this is well before the djent thing, but when I was doing that stuff with the seven-string, I instinctively knew there was going to be kids that saw the seven-string and recognized a completely different potential for it."

When you listen to that record now, are there any sections of which you remain particularly proud?

"Well, as far as the music itself goes, I think it stands up! It didn’t sound trite or forced and it doesn’t sound too dated to my ears. On some of the tracks, I was able to really kind of bust my nut, as they say. I love listening to a track like Kittens Got Claws with that intro with all of those cat sounds - that’s all guitar!

"I listened to that not long ago and I wondered how I did all that cat stuff. In retrospect, when you look back at something like that, you learn a lot about who you were at the time, and I was a very different person.

"My trajectory from my bedroom to Frank Zappa to Alcatrazz to the Roth gig was pretty uncanny, and as I started to really hit the scene, so to speak, it was awkward feeling when I started getting recognition. At one point, I honestly couldn’t really figure out what people saw in my playing.

When I was in Whitesnake I was probably experiencing more of my pretentious nature than I ever had before

"Then you start winning Grammys, you win every guitar poll and you’re on the cover of every magazine, there’s tons of money coming in and everyone’s telling you how great you are and the ego comes in through the backdoor, and it starts to infiltrate you without you even knowing it!

"It can kill creativity, but it also becomes an attention demander. There was a period there when I was in Whitesnake where I was probably experiencing more of my pretentious nature than I had ever before and I don’t think I was that easy to deal with."

Surely many would say that attitude is part and parcel of a gig like that. Would you not agree that at least a touch of that ego and attitude was required to pull off a gig like Donington?

"I don’t know. I’ve worked with a lot of people and we’re all caught up in our ego - that’s just across the board - but it reflects into the world in different ways. I think what you’re really referring to is confidence, and that’s what it boils down to.

"That’s something I had in truckloads and I had no doubt that I was going to get on that stage and play my ass off and be a rock star - for the people! The guitar is such a focused instrument and people love rock guitar and they want to see you blow up the bridge.

"They want to see you be that guy and I was all too happy to be that guy and I was fiercely confident in everything I did. When it came time to do the guitar parts on any of those records, whether it was replacing Yngwie or the Roth gig, it was always like, “Yeah! Let me at it! I know what I’m gonna do, stand back!”

What’s it like looking back on that whole experience as we mark 30 years of Slip of the Tongue?

"It ticked all the right boxes for me because I didn’t have to front the band, I had the greatest lead singer in the world at the time, and I was treated like a king. The guys in the band were just fantastic and they were gentlemen. Rudy Sarzo is the nicest guy in the world. Tommy Aldridge is hilarious and gifted. Adrian Vandenberg was fantastic; very cultured, liked good things, killer player with good tone! And they all tolerated my attitude and pretension brilliantly.

"To this day I remain very happy with the record itself and I think it stands up as a great-sounding record, even if it may be a little different from the rest of the Whitesnake albums."