The 100 greatest guitarists of all time

A comprehensive rundown of the best guitarists of all time, featuring the trailblazers, the early innovators, the best jazz, rock, indie, blues, metal and acoustic players – and the top guitarists around today...

The best blues guitarists of all time

1. Stevie Ray Vaughan

Stevie Ray Vaughan brought physicality and soul to guitar playing, and he brought it in spades. The soul came through the speaker. The physicality was there for all to see. To watch him play, there were occasions in which SRV would throttle the guitar as though it were an arm wrestling contest at last orders in a Nantucket alehouse.

His strings were the stuff of legend – 13s? No, 14s; 17s! Heck, some might argue he used piano wire. Either way, he went down the heavy-gauge route and had the dexterity to manipulate them as though they were dental floss. This, the fire in his belly, and the tone-gussying Tube Screamer playing mediator between Fender Strat and amp give him a range of dynamics that few, if any, players could match.

And yet, there was a tenderness to his playing. There are many who argue that his cover of Jimi Hendrix’s Little Wing eclipses the original. That’s for debate. What is not is that Vaughan, who was only 35 years old when he died in a helicopter crash, he left an over-sized impression on guitar culture in a short space of time. Just like Hendrix.

His debut studio album with backing band Double Trouble, Texas Flood, remains a blue-chip classic of the genre, and showcases the range of those dynamics. That title track – a cover of the 1958 Larry Davis number – could convince you that the sun never shines on Texas, least not while Vaughan was in it.

The likes of Pride and Joy and Tell Me demonstrate what he could do with a groove behind him. Sadly, generations won’t get to see him onstage, but so long as sets such as those at Montreux in 1982 are available on YouTube and DVD, more will bear witness to this singular talent.

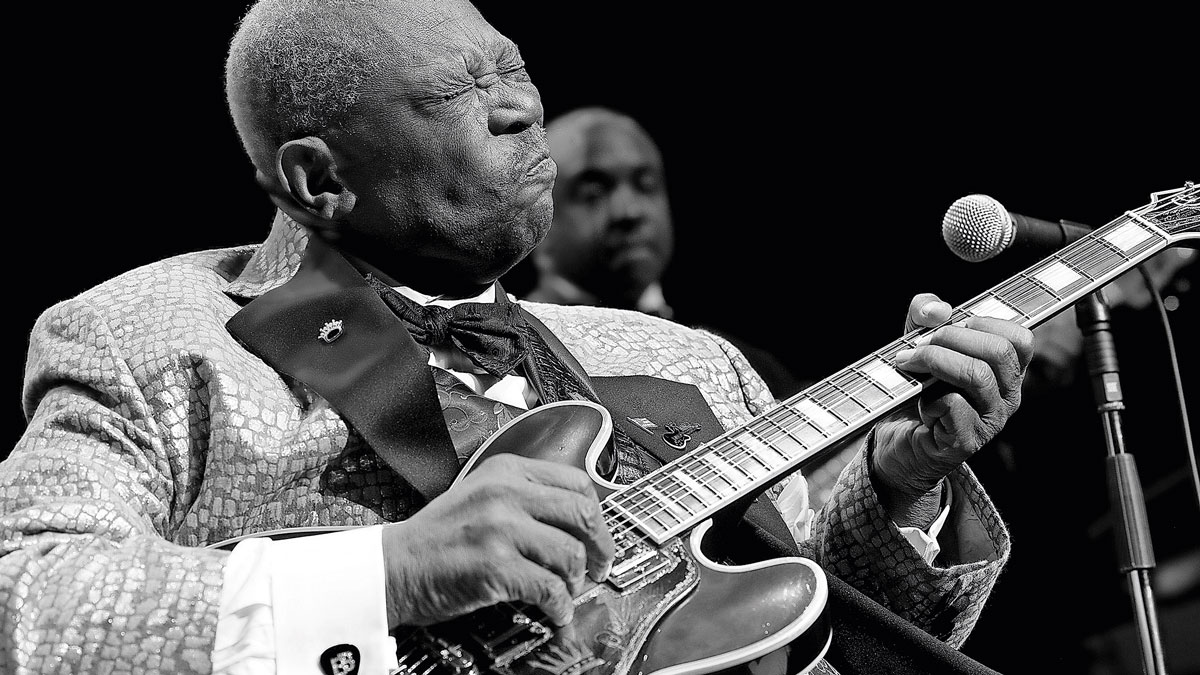

2. B.B. King

B.B. King was pure class, from his exquisite licks to his heartfelt vocals. Brought up on a plantation in Itta Bena, Mississippi, he was born Riley B. King in 1925.

King attended various churches, attracted to the blues-tinged gospel songs they sang. His pastor taught him three chords before his plantation boss advanced him the money to buy his own guitar.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

King taught himself to play and by 1946 had moved to Memphis with his cousin, slide guitarist Bukka White. Before long he was playing on local radio and scored a residency at a West Memphis grill. King soon gained his own show, where he was dubbed ‘Beale Street Blues Boy’, shortened to ‘Blues Boy’ and then ‘B.B.’.

At this time he was still playing acoustic guitar, but influenced by his hero T-Bone Walker, King moved to electric. He initially played a Gibson ES-150, then an ES-5 Switchmaster, even a Fender Esquire, before finding the instrument with which he will forever be associated, the Gibson ES-355 thinline.

King named his guitars ‘Lucille’, after a fight over a woman of that name caused a burning oil drum heater to overturn. King ran back into the blazing building to retrieve his beloved instrument, and christened it (and every subsequent guitar) in her honour.

Several elements make King’s style unique. Prior to King, few guitarists used vibrato with such artistry, but he loved the fluttering sound of slide guitarists such as cousin Bukka White, and the powerful quiver created by blues harmonica player Little Walter. So he developed his own, by quickly rotating his finger while holding down a fretted note.

It made his licks sound more vocal, and set him aside from others. Also, King considered his singing and playing equal partners in his success, so rarely played chords while he sang, instead devoting each moment to a sung or played line, thus heightening each one’s intensity.

In his early years, King followed the five-shape fingerboard template laid down by T-Bone Walker and others, but before long discovered a fretboard position that suited him perfectly. We now call this ‘the B.B. box’. Essentially ‘shape 3’ in the pentatonic scheme, King pivoted his first finger on the root note of the key, on the second string – in A this would be 10th fret.

From here he could easily reach a 5th above (first string, 12th fret), find b5th and 4th one and two frets down, and 2nd, b3rd and 3rd on the second string, 12th, 13th and 15th frets respectively. One string down on the 11th fret was the major 6th, so all these important notes were easily available within one small area – and that’s before we take into account King’s incredible string bending.

When the white blues boom of the 1960s exploded, artists like Eric Clapton, The Rolling Stones, and Paul Butterfield used their success to champion their own heroes. Thus artists like King, who had previously been dubbed “race” acts, gained the mainstream appreciation that they rightly deserved.

3. Buddy Guy

The world’s greatest living bluesman, Buddy Guy is a master showman and storyteller. He was born in Louisiana, the son of sharecroppers, and would migrate north of the Mason-Dixon to Chicago where he make his name and become one of the foundational giants of the city’s blues scene. Otis Rush invited him onstage to play, and he would learn what works by looking at the audience’s faces. If they liked it, he gave them more. And he would give and give.

He would walk through the crowd, engage with them, then jump off the bar with his guitar so they’d surely remember his name. These tricks he would learn from Guitar Slim. People soon called him the ‘Little Wild Man from Louisiana’.

Guy soon had to find a more robust guitar than the semi-hollow Guild Starfires he played at first. He needed a solidbody, and the Fender Stratocaster became his weapon of choice. His super-juicy tone influenced Hendrix, all the young British dudes – Beck, Clapton et al.

If he heard a horn part he liked, he would try play it on guitar, expanding his repertoire, finding notes that others missed. Polka dots would become a trademark. Only Minnie Mouse wore them better. But no-one puts on a show quite like Buddy Guy.

4. Albert King

Born Albert Nelson in 1923, Albert King stood 6’ 4” and weighed 250lbs. Like B.B. (no relation, although Albert often fudged the reality), was born on and worked on a cotton plantation in Indianola, Texas.

King fashioned his first guitar from a cigar box, with a tree branch neck and strung it with a strand of broom wire. When he finally got a guitar, being left-handed he simply turned the right-hander upside down and played with the strings reversed. He also tuned very loosely – Gary Moore told Guitarist magazine that while working with King he took a sneaky peak and found it to be C# F# B E G# C#.

Nicknamed The Velvet Bulldozer due to his huge size but sweet singing voice, Albert played simply but beautifully on his 1958 Gibson Flying V

This down-stringing made his action very pliable. Albert could play a whole lick by bending his top string by a 4th and letting it down to create other intervals.

After various attempts at a record deal he moved to Memphis and was signed by soul label Stax, with superb house band Booker T & The MG’s. The MG’s backed King on his legendary 1967 album Born Under a Bad Sign which contained the brilliant Crosscut Saw, The Hunter (covered by Free), Oh Pretty Woman (covered by Gary Moore) and the title track (covered by Cream).

Nicknamed The Velvet Bulldozer due to his huge size but sweet singing voice, Albert played simply but beautifully on his 1958 Gibson Flying V. You can hear huge slabs of him in the playing of Stevie Ray Vaughan, Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix and Joe Walsh among others.

5. Joe Bonamassa

You kind of get the impression from Joe Bonamassa that his position as the highest-grossing blues artist of all time is a little embarrassing – thrilling, sure, but it’s quite the affirmation. Perhaps this is why he has made it his life’s mission to widen the blues’ appeal.

There’s the KTBA blues cruise, the label, the production, Nerdville... But ultimately, Bonamassa leads with his fingers when it comes to advocacy, toting a muscular, pyrotechnic style that not only references the '60s British blues scene, and the pantheon of electric blues greats, and classic rock and prog when the song requires it.

6. Robert Johnson

Arguably no musician has ever been the subject of such incredible mythology as Robert Johnson. Would rock ’n’ roll ever have given us Sympathy For the Devil and Highway To Hell and if not for rumours of Johnson selling his soul at the crossroads? Would metal fans be scrawling pentagrams on guitars and throwing the horns if Johnson hadn’t sung Me and the Devil Blues?

Beyond the incredible imagery, there’s a sophistication and variety to Johnson and his delta contemporaries that modern blues often lacks. The art form is often reduced to endless 12-bars, while Johnson’s own work embraced jazz and country. His blues compositions did not limit themselves to the 12-bar format, and his debut recording, They’re Red Hot, was an uptempo ragtime number.

With his singing and slide playing, he even explored microtonality in subtle ways that Jeff Beck and Derek Trucks are showered with praise for achieving today

Playing unaccompanied allowed Johnson and his contemporaries the freedom to play with time and tempo, and his songs have odd-length bars in unexpected places. With his singing and slide playing, he even explored microtonality in subtle ways that Jeff Beck and Derek Trucks are showered with praise for achieving today.

Musical immortality is mostly about having great songs. Beyond the legend, Johnson’s name still looms so large because he wrote tunes that slap. Dust My Broom, Crossroad Blues and Sweet Home Chicago are the blues’s biggest standards.

The Rolling Stones covered Love in Vain and Stop Breaking Down, Led Zeppelin had Traveling Riverside Blues and The Lemon Song, while Steve Miller and Duane Allman both took a bite at Come On in My Kitchen. Guitarists like Ike Turner and Chuck Berry evolved Johnson’s template into rock ’n’ roll, and from that came a slew of hits.

It’s not quite right to give the credit solely to Johnson. Delta blues musicians shared their creativity with each other more freely than today’s copyright-driven music industry.

Johnson’s music carries plenty of influence from his and forebears and peers, some of whom are now forgotten. Johnson might be the most important musician in the development of 20th century popular music, but he’s also emblematic of dozens of black folk musicians who developed the genre without the pay or credit they deserved.

Still, if you want to learn acoustic blues fingerstyle, Johnson’s turnarounds are still the benchmark. If you want to play slide, you’ll need to learn his licks. And if you’re writing songs, you can only hope to capture an element of the human experience so profoundly as he did.

7. Rory Gallagher

The Irish guitar maverick would stand astride the boundaries of blues and rock, showcasing a virtuoso electric style – and a sound – that would resonate through popular culture. Brian May started using a Rangemaster treble booster through a Vox AC30 on account of him.

Gallagher made his name in the early ‘70s with Taste, later going solo, and adhering to the cardinal rule of blues that it must be authentic. On that score, he would give the blues a Celtic flavor, drawing influence from skiffle and folk.

He was nifty with a slide, on acoustic, whatever. You just had to give him a guitar, then pray for its finish. He was hard on them, as his heavily weathered Strat could confirm.

8. Muddy Waters

Six-time Grammy winner McKinley Morganfield ruled the Chicago blues scene from the mid 1940s on. Moving from Clarksdale, Mississippi in 1941 and switching from acoustic to electric guitar two years later, Morganfield (now Muddy Waters) assembled a band of the finest players in town, including Little Walter (harmonica), Otis Spann (piano) and Jimmy Rogers (guitar).

Live, Muddy’s band was a powerhouse. Jimi Hendrix found it terrifying – “I first heard him as a little boy and it scared me to death,” quipped Jimi, who took a famous Muddy lick and turned it into Voodoo Chile. Muddy’s playing was almost primeval.

Bluesman John P Hammond stated, “Muddy was the master of just the right notes; profound, deep and simple.” Although he wrote songs, he is mainly remembered for covers that became the definitive versions, such as Rolling Stone (from which both magazine and band took their name), Got My Mojo Working, Mannish Boy, and Hoochie Coochie Man.

Muddy was rarely seen without his red Fender Telecaster, on which he mostly played slide and the occasional riff, but his legend and musical influence remain almost unequalled. As B.B. King put it, “It’s going to be years before people realise how great his contribution was to American music.”

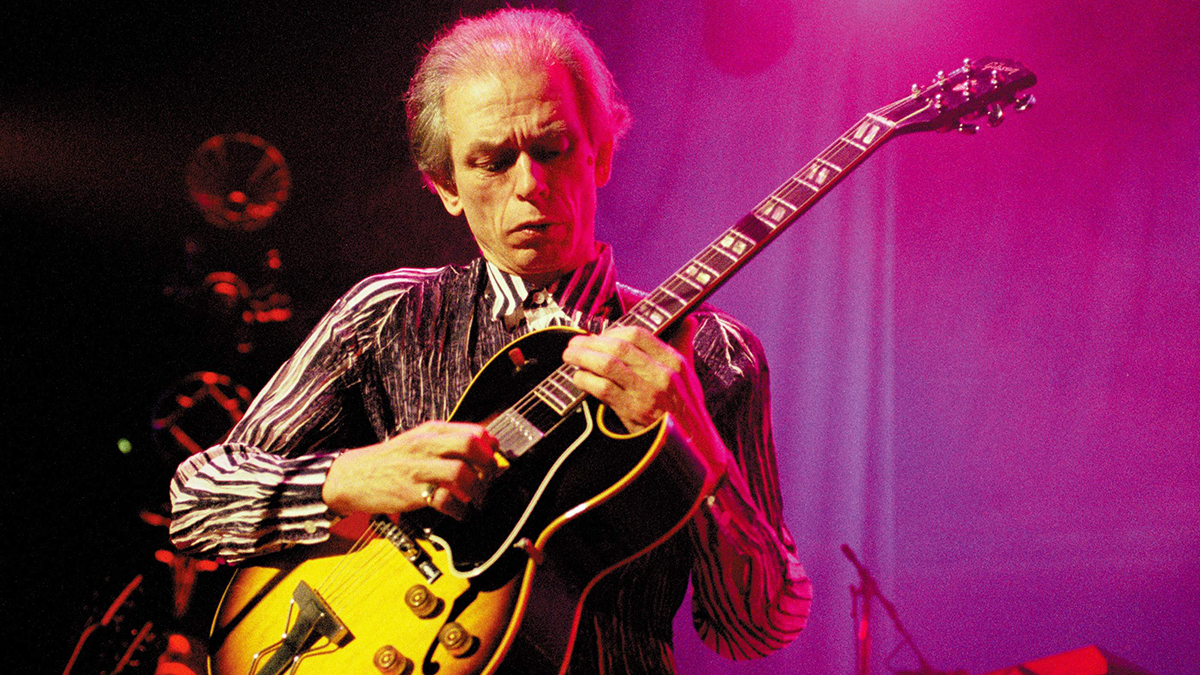

9. Johnny Winter

Johnny Winter was born in Beaumont, Texas, in 1944, and grew up with music all around him. He started cutting records age 15, and got his big break in 1968 when Mike Bloomfield invited him to play in New York, Columbia Records paid attention and gave him a record advance. His debut album, 1968’s The Progressive Blues Experiment, showed which way the wind was blowing.

Winter would enjoy a prolific career, making the angular silhouette of the Gibson Firebird his calling card – most notably his 1964 Polaris White Firebird V – but so too his slide chops and fierce attack, the flurry of triplets and double-stops. Like many blues players of his age the influence of Muddy Waters was writ large in his style. Winter would repay the favor, jamming with Waters and producing three studio albums for him.

10. Freddie King

Of the legendary ‘Three Kings’, Freddie was the youngest and most raucous. His guitar style was fast and ferocious, with huge string bends and vicious vibrato, his vocals almost guttural in their delivery.

Born in Gilmer, Texas in 1934, Freddie learned guitar from age six, but moved to Chicago while in his teens. Freddie would sneak into the blues clubs and watch legends like Muddy Waters, Elmore James and T-Bone Walker. He took onboard their stagecraft, marvelled at their musicianship and determined to make it big, just like them.

But after continual rejection by Chess Records on Chicago’s South Side he finally struck a deal with Federal Records on the city’s West Side, where a hipper blues scene was burgeoning. Freddie became a hit in the clubs here, and his first single for Federal would become a standard – Have You Ever Loved a Woman, later a staple in Eric Clapton’s career.

Freddie influenced a raft of later white guitarists, like Clapton, Peter Green, Michael Bloomfield and Stevie Ray Vaughan. His instrumentals became legendary – Hide Away, The Stumble and San-Ho-Zay, among others – and he will also be remembered for having one of the first mixed race bands. Freddie was hard working and hard living, and died of pancreatitis, aged just 42.

Also in the running…

Samantha Fish

With her four-string cigar box guitar, Fish evokes the rawness of early bottleneck recordings, plus punk levels of aggression.

Peter Green

No other British blues boomer matched Greeny’s subtlety or his precise bends. His dynamic control evoked an aching longing.

Elmore James

By pioneering electric slide guitar and loud, dirty amplifiers, James gave us Dust My Broom, and the blues-rock blueprint.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe

Long overlooked, it’s now recognised Tharpe turned Gospel into rock ’n’ roll. Her electrifying performances inspired Chuck Berry and co.

Jeff Healey

With guitar flat on his lap, the blind Healey found new levels of control over bends, slides, and vibrato.

John Mayer

Proving that blues can still sell, Mayer puts Hendrix and SRV vibes into memorable pop songs, breaking the 12-bar rut.

Derek Trucks

His mastery of microtonality – the pitches in between the frets – plus glorious phrasing makes Trucks’ slide playing uniquely compelling.

Gary Clark Jr.

Wisely chosen to pay tribute to BB King at the 2016 Grammy awards, Clark is authentic without just rehashing the all old stuff.

Current page: The best blues guitarists of all time

Prev Page Intro + best rock guitarists Next Page Early innovatorsJonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to publications including Guitar World, MusicRadar and Total Guitar. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.