“We didn’t realize we were breaking up as it was happening”: The Beatles intended to go back to their roots on Let It Be – instead, they documented the collapse of their magical creative partnership

A mix of rootsy, spirited rockers, stunning ballads, and unfocused jams, Let It Be captured the Fab Four looking to find their footing as a group again

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As 1968 came to a close, the Beatles were for the first time in a state of creative limbo. In late November of that year, they’d released The Beatles, their sprawling double-disc effort popularly known as the White Album. The record showed an impressive creative breadth, yet it revealed the band’s lack of focus with its assortment of disparate songs, many of which were recorded without the participation of the full band.

While the White Album was an unqualified success at retail, critics were sharply divided in their estimation of it. Nowhere was this more evident than in the New York Times, where it was deemed a “major success” by one reviewer and “boring beyond belief” by another.

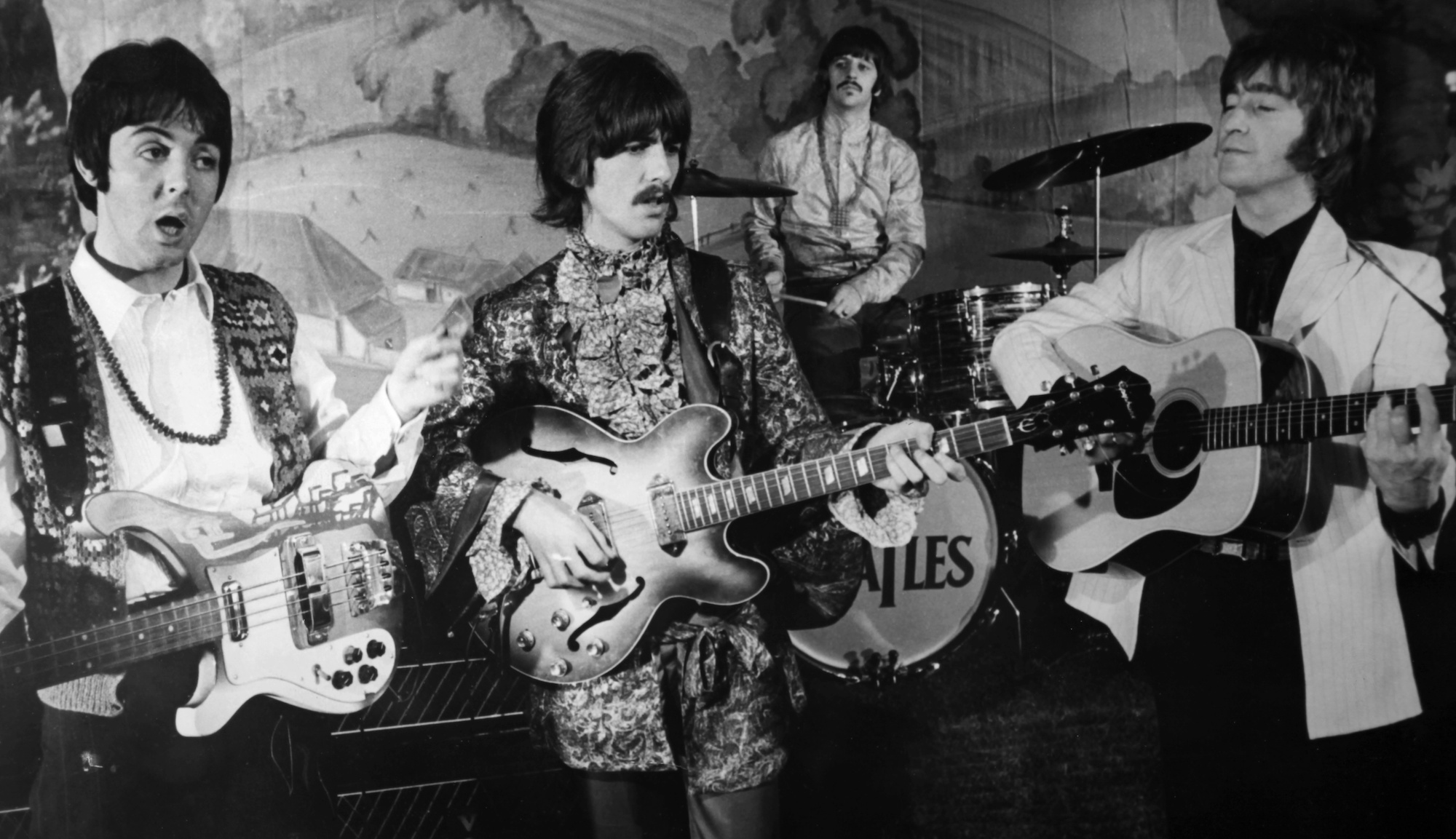

The start of a new year is a traditional opportunity to take stock of one’s circumstances and begin anew. Certainly, that’s what the Beatles had in mind when, on January 2, 1969, they convened for the first time since the White Album sessions to begin work on a new project titled 'Get Back.' Dreamed up and orchestrated by Paul McCartney, the effort was designed to get the foursome back on track, working together as a single entity and recording live in the studio, with no (or minimal) overdubs, as when they’d made their first recordings for EMI in 1962.

The project would entail an album, a film and, somewhere along the way, a live performance, the first since the Beatles quit performing publicly in 1966. Altogether, the sessions might have resulted in something great. Instead, they gave the world Let It Be, an album (and now out-of-print companion film) that showed the Beatles coming apart rather than coming together.

Let It Be has always been an anticlimax to the Beatles’ stellar career. John Lennon himself famously pronounced the album “the shittiest load of badly recorded shit with a lousy feeling to it ever.” George Harrison called the sessions simply “hell” – quite a statement coming from a spiritual seeker.

We didn’t realize we were breaking up as it was happening

Paul McCartney

The disc stuck in McCartney’s craw for decades, to the point where, in 2003, he oversaw the remixing and remastering of the project, which resulted in the album Let It Be... Naked.

Indeed, Let It Be documents a great band – arguably the greatest rock band ever – in the process of disintegration. For that reason it is both fascinating and frustrating. “We didn’t realize we were breaking up as it was happening,” McCartney later said of the recording process.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Chronologically speaking, Let It Be isn’t the Beatles’ final set of recordings. That would be Abbey Road, which was recorded the following summer and is widely considered to be one of the finest works in the group’s catalog. But the difficulty of compiling an album from the tense and troubled sessions delayed the release of Let It Be again and again. In the meantime, Abbey Road was released, in September 1969, leaving Let It Be to serve as the Beatles' swan song, a somewhat sorry ending to an otherwise glorious career.

There is an immense amount to be learned from half-finished or failed songs by great songwriters. And while Let It Be felt disappointing to Beatles fans when the album was first released in May 1970, we now live in an era of bonus tracks and revisionist compilations of previously unreleased studio outtakes and in-concert meanderings by classic rock artists. These days, we’re better equipped to deal with CD releases of uneven or dubious quality than audiences were in 1970.

By today’s standards, Let It Be is actually quite a package. It’s got three bona fide McCartney-penned hits: Get Back, The Long and Winding Road, and the title track, plus the Lennon classic Across the Universe (actually recorded in early 1968, rather than during the Let It Be sessions).

That’s more than enough for the digital download age, now that the idea of the rock album as art form has all but passed into history. But the rock album was just coming into its own back in 1969, thanks to masterworks like the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the Rolling Stones’ Beggars Banquet, and the Who’s Tommy – albums where every song was a winner and/or contributed to a cohesive overall musical vision.

Then again, 1969 was a funny year. For every triumph like Woodstock, there was a tragedy like Altamont. It was the year the Jimi Hendrix Experience broke up and Brian Jones died. The hippie dream was unraveling.

The Beatles were certainly beat up at the dawn of that year. Six years of intense, unprecedented fame had taken their toll on the group’s sanity. They’d been running a bit rudderless ever since the death of their manager Brian Epstein, in 1967. Tensions between the band members flared up during the making of the White Album, opening a rift between them that had not begun to mend by the time the Let It Be sessions began.

Apple Corps, the multifaceted enterprise they’d established in 1968, was rapidly going bankrupt, and business differences had bitterly divided the group’s members. Lennon, Harrison and Starr had decided to assign management of the Beatles to New York businessman Allen Klein, while McCartney wanted to go with the New York law firm of Eastman & Eastman, run by the family of his new girlfriend, and soon-to-be-wife, Linda Eastman.

As a backdrop to all of this, the Beatles had simply grown apart as people, as often happens with bands or groups of friends who get together in their teenage years and later forge incompatible adult identities.

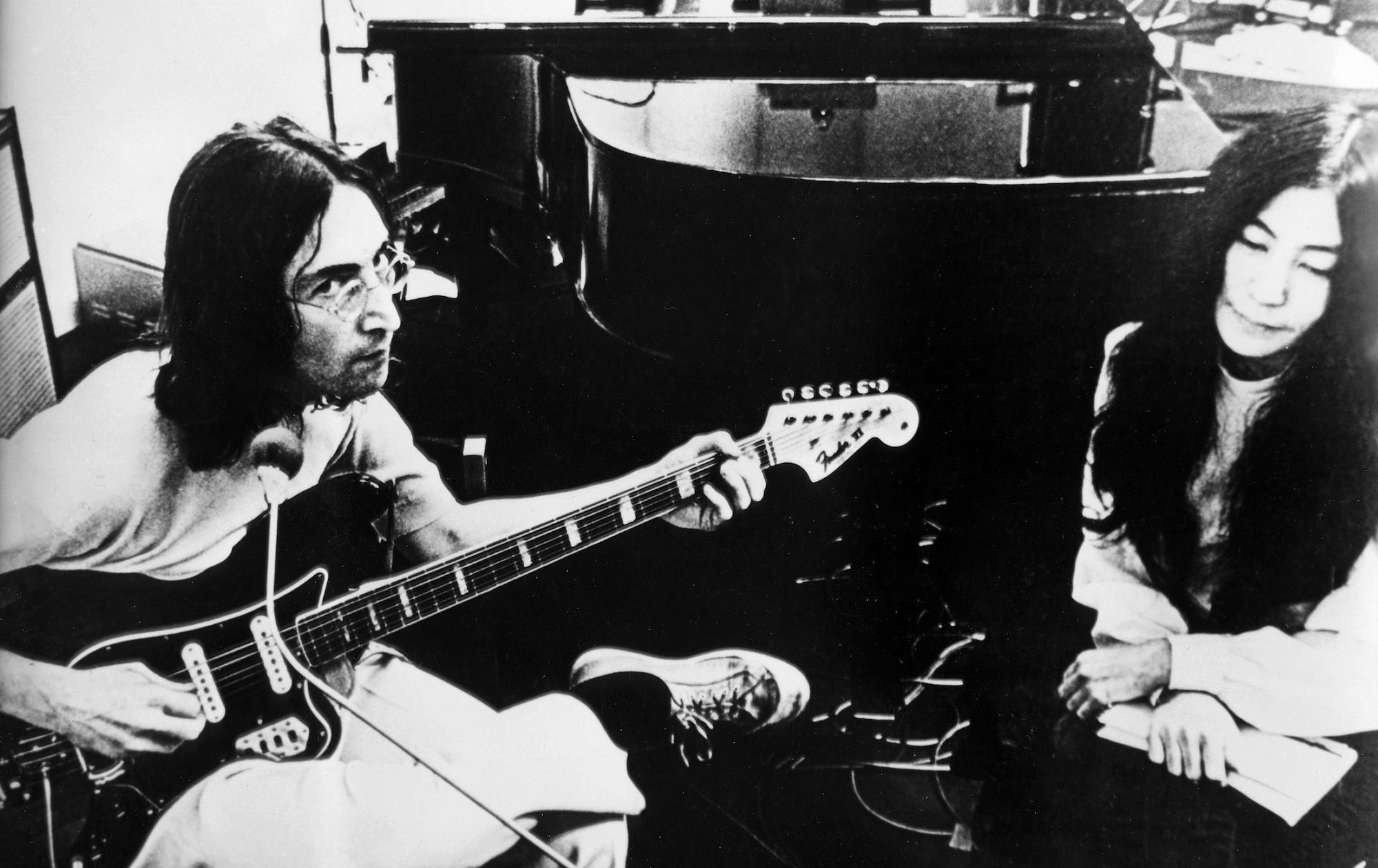

George Harrison had become deeply involved in the spiritual traditions of India. Lennon had gotten into spirituality, radical politics and the avant-garde art world of his new girlfriend, and future wife, Yoko Ono. Indeed, both Lennon and Harrison seemed ready to move on from their teenage band. Starr, increasingly insecure about his role, had quit the Beatles once, briefly, in 1968.

The only thing we haven’t got for every song is the song

Paul McCartney

But McCartney desperately wanted to keep the Beatles together. To his way of thinking, the way to do that was to get the group back to its roots in live performance, something they’d abandoned in 1966. He floated the idea that the Beatles should do a concert in front of a live audience that would be filmed and used to create a one-hour television program.

It was a modest proposal at first – a one-hour concert TV show. But things quickly got out of hand as band members dreamed up an increasingly ambitious, expensive and unmanageable series of potential venues for this return to live performance – a Roman amphitheater, an Arabian desert, an ocean liner (or maybe two), a rooftop in India.... And that was just the beginning.

McCartney’s original plan called for the band to perform a greatest-hits set, but the idea soon emerged to write a whole new set of songs for the project. While it was an excellent idea in theory, the Beatles were pretty well tapped out – nearly all their song ideas had gone into the double-disc White Album. As McCartney quipped during the sessions, “The only thing we haven’t got for every song is the song.”

Nonetheless, on January 2, 1969, Lennon, McCartney, Harrison, and Starr assembled on a soundstage at Twickenham Film Studios in London to begin rehearsals and songwriting for the project, which had acquired the working title 'Get Back,' signifying the band’s proposed return to their roots. Also on hand was a film crew under the direction of filmmaker Michael Lindsay-Hogg. In the absence of a definitive decision on a concert venue, the plan was to start shooting rehearsals, just to get something in the can.

McCartney should have known better. He had tried a similar strategy shortly after Epstein’s death with the ill-fated Magical Mystery Tour – get a camera crew, pile onto a bus, start shooting with no script or coherent plan in mind, and see what happens. What happened then was the Beatles’ first-ever critical flop. And that was when the band members were still on relatively good terms.

What happened at Twickenham was considerably grimmer. All the inter-band tensions of the White Album sessions quickly reasserted themselves, now exacerbated by the looming presence of film cameras and crew. As in the past, McCartney, Harrison, and Starr had a hard time tolerating Yoko Ono’s presence and very vocal involvement in the musical process, sitting close by Lennon’s side throughout the rehearsals. And McCartney, desperate to pull the whole thing together, became over-assertive.

He clashed with Harrison in particular. McCartney had always been quite hands-on with the Beatles’ lead guitar work, playing some of the band’s most notable guitar solos, including Taxman and Good Morning, Good Morning, himself.

Harrison had always accepted this with good grace. The youngest member of the Beatles, not to mention the youngest child in a large family, he’d always fit into something of a “kid brother” role, eager to please and deferential to his elders. But on January 10, 1969, Harrison’s carefully cultivated meditative serenity failed him. He lost his cool and quit the Beatles, storming out of Twickenham and calling derisively over his shoulder, “See you ’round the clubs.”

It was all captured on film and would eventually become part of the feature film, Let It Be. Following Harrison’s angry departure, Yoko Ono took up the seat he had been occupying and joined the three remaining Beatles in a free-form noise jam, lending her signature improvised vocal ululations to the proceedings. The tacit implication seemed to be that vocal performances of this nature could fill the space formerly occupied by Harrison’s lead guitar in the Beatles music.

Harrison rejoined the Beatles five days later, on the strict condition that all plans for a live performance be scrapped. The project would now be, in essence, a live-in-the-studio, back-to-the-roots Beatles album, with film cameras on hand to document the rehearsal and recording process. Late in January, the Beatles left Twickenham and adjourned to their new recording studio in the basement of Apple HQ, in London’s Savile Row. But more trouble awaited them there.

Construction of the new studio had been entrusted to Alex Mardas, a friend of the band’s who had been appointed head of Apple Electronics. “Magic Alex,” as Lennon had dubbed him, was certainly a visionary. His ideas for the Beatles’ studio included creating an invisible force field around Ringo’s drums, to control mic leakage, and a 72-track recording system, with a separate speaker for each track, no less. (This was at a time when eight-track was still the standard format, with 16 tracks just on the horizon and seeming quite futuristic.)

The problem was that Magic Alex lacked the technological know-how to make any of his visions a reality. The Apple studio was just about totally dysfunctional. As the studio’s inaugural Beatles sessions got underway, a hasty request was sent to EMI’s Abbey Road for two four-track mixing consoles to go with Apple’s eight-track tape machine, one of the few pieces of gear in the place that actually did work.

On January 22, the Beatles finally got down to some serious recording at Apple. While their longtime producer George Martin was present at some of the sessions, his role was minimal this time. John Lennon – a man with an insatiable appetite for biting the hand that fed him – had ordered that there was to be none of Martin’s usual “production nonsense” for this project. Let It Be would become the only Beatles record not produced by Martin.

The results serve as a dramatic testimonial to Martin’s key role in the Beatles and a clear lesson in why a producer is vital to the recording process.

Instead, the band hired Glyn Johns to act strictly as a balance engineer. Johns had previously distinguished himself with his engineering work on the Rolling Stones’ Beggars Banquet, and he had served as engineer on Led Zeppelin’s debut album, which was released in January, during the Let It Be sessions.

Also in the control room was another soon-to-be studio legend, Alan Parsons, who would go on to engineer Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon and garner considerable radio airplay with his own Alan Parsons Project.

As session tapes and logs make clear, McCartney was the only Beatle who came to the sessions having completed his songwriting homework. By the third day of recording, the band had assayed Paul’s Two of Us, a tuneful, if somewhat lightweight, track, packed with melodic hooks and one of those picture-perfect McCartney bridges. Soon after, McCartney’s Get Back, Let It Be, and The Long and Winding Road were duly committed to tape.

What’s interesting about McCartney’s big Let It Be compositions is that they all contain references to going back home or moving backward to some more secure time or place. Of the four Beatles, McCartney was the one who most wanted the quartet to “get back” to where they once belonged, to paraphrase a line from his song Get Back.

As for the song Let It Be, it is often taken as one of McCartney’s most overtly religious statements. However, the “Mother Mary” invoked in the song’s lyric is not the Blessed Virgin of Christian tradition but rather McCartney’s own mother, whose name was Mary, and who died when Paul was 14. This loss helped form an early bond between McCartney and Lennon, who also lost his mother at an early age.

In interviews about the song, McCartney has mentioned that, in times of crises, he would indeed see his mother in dreams or otherwise feel her comforting presence. In this sense, Let It Be is a field day for Freudians. With the band that brought him fame and fortune falling to pieces, McCartney wants to regress to the womb.

The Long and Winding Road, with its repeated refrain, “and still it leads me back,” also expresses a wish to move backward in time, to stability and security, although here the wish is couched in terms of a romantic relationship, the more conventional context for pop song lyrics.

In a sense, The Long and Winding Road is a gateway to McCartney’s post-Beatles solo career, with its celebration of domesticity – the cozy comforts of home; family, the well-stuffed armchair, and a nice cup of tea. While these themes were always present in McCartney’s songwriting, they move to the foreground post-1970. But on Let It Be, McCartney at times veers too far in this complacent direction.

The Long and Winding Road, in particular, crosses the thin line dividing sentiment from sentimentality. It’s easy to see McCartney’s Let It Be tracks as the dawn of his “adult” songwriting phase, far from the adolescent vigor of rock and roll.

While McCartney embraces the comfort of fuzzy, warm nostalgia, Lennon aspires to the shock of unsettling and outlandish wordplay. Absurdist nonsense rhymes had been a part of Lennon’s creative modus operandi ever since school days. This prolix urge found an outlet in Lennon’s first two books, In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works. In the Beatles’ earlier career, Lennon had learned to place his hyperactive verbal imagination at the service of the boy-meets-girl lyrical conventions of the day.

But, when Bob Dylan and psychedelic drugs liberated rock lyrics from those strictures, around 1966, Lennon’s muse was set free. The result was heard in imagistic Beatles classics like Strawberry Fields Forever and I Am the Walrus. But by the time of the Let It Be sessions, Lennon was relying too much on his gift for spontaneous poetic non-sequiturs.

Perhaps this is attributable to the influence of Yoko Ono and the Fluxus art movement, with which she was associated, and which held the firm conviction that anything nonlinear is ipso facto profound and arty. That concept seems to be behind Lennon’s lyrics to tracks like Dig a Pony and Dig It.

As nonsense song titles go, there isn’t much distance between I Am the Walrus and Dig a Pony. Both seem like jokey working titles for songs in the early stages of development, but that’s where the similarities end. As for the differences, one might look to George Martin’s inspired orchestral and arrangement work on I Am the Walrus.

Lacking any cohesive narrative or theme, the song derives its exposition from Martin’s arrangement and production, which highlight the Zen resonance of Lennon’s lyric. But by banning what he called Martin’s “production nonsense” from the Let It Be sessions, Lennon prevented his own songs from receiving the benefit of Martin’s talents.

Dig a Pony certainly could have used the producer’s help. Unlike I Am the Walrus, which coupled imagistic lyrics with some of Lennon’s most inventive music ever, Dig a Pony marries his lyrical abstractions to a fairly standard-issue R&B chord progression.

Lennon’s muse seems to desert him utterly when the chorus hits, leaving him to serve up the punch line, “All I want is you.” The song’s distinctive riff is certainly strong, with bluesy elements and a suggestive groove, but the Beatles seem unable to rally their forces and perform it with conviction.

And then there’s Dig It, another loosely constructed Lennon track. It isn’t even a song, merely an exercise in free-form glossolalia set to the chorus of Dylan’s Like a Rolling Stone. It seems like just a rehearsal-hall lark, but the Beatles actually attempted to record it on two consecutive days, suggesting that Lennon had designs on the jam becoming something more cohesive. One version went on a full 12 and a half minutes, of which less than a minute was deemed worthy of release.

When it came to Let It Be we couldn’t play the game anymore.

John Lennon

Even when they worked together, Lennon and McCartney were unable to conjure up the magic they had in the past. I’ve Got a Feeling makes this evident. McCartney tries to shore up his mere two verses with a riff, a bridge and some of his best Little Richard–style screaming, but the song is desperately crying out for a chorus.

Rather than deliver the goods, Lennon just turns on his “Dylan goes Fluxus” faucet, free-associating over McCartney’s two overworked verse chords with scarce melodic content: “Everybody had a hard year, everybody had a good time,” and so on. It’s more than a little reminiscent of his “everybody’s got one” coda on I Am the Walrus, but less than half effective.

What Let It Be makes clear is that McCartney and Lennon, one of the greatest songwriting teams of all time, have become like two ships passing one another on a foggy night, each unaware of the other’s presence, or out of one another’s depth.

“When it came to Let It Be we couldn’t play the game anymore,” Lennon later remarked. “We’d come to the point where it was no longer creating magic, and the camera being in the room with us made us aware that it was a phony situation.”

The unreleased tracks from the sessions bear this out. Unable to get together on the new material, the Beatles delved into the past, jamming on old Fifties rock and roll tunes they’d loved growing up, old music hall songs, and even some of their own earliest material.

The Let It Be track The One After 909 was one of the first songs Lennon and McCartney wrote together, and the Beatles had even attempted to record it at one of their earliest sessions, in March 1963. It’s telling that this adolescent Lennon/McCartney effort outshines some of the “mature” work on Let It Be.

Certainly, Let It Be didn’t suffer from a lack of musical ideas but rather from the group’s inability to bring many of them to fruition. Among the songs that various Beatles brought into the room were the future Abbey Road classics Oh! Darling and I Want You (She’s So Heavy), as well as Isn’t It a Pity, which would emerge on George Harrison’s solo album All Things Must Pass, and Teddy Boy, which McCartney recorded for his self-titled first solo album.

Was it George Martin’s absence that kept these songs from reaching full realization in early 1969? Was it the film cameras’ all-too-palpable presence? Or was it simply the wrong time and place?

One composition that does come together quite nicely on Let It Be is Lennon’s R&B inflected Don’t Let Me Down, which was released as the flip-side to the album single Get Back. The song’s stripped-down, soulful style renders it quite amenable to McCartney’s original idea of recording live in the studio. The tempo and chord changes are ideally suited to the scrappy tone of Lennon’s Epiphone Casino, McCartney’s ’63 Hofner bass, and the bright, rhythmic comping of Harrison’s newly acquired rosewood Fender Telecaster.

There’s also something incredibly poignant in the sight and sound of Lennon and McCartney facing one another amid these troubled sessions and repeatedly singing the line, “Don’t let me down.” It’s a plea that encapsulates the sad mood of their crumbling creative partnership, as well as the feeling of Beatles fans everywhere as they watched their idols chip to pieces and disintegrate.

Don’t Let Me Down is one of the Let It Be tracks greatly enhanced by the presence of American keyboardist Billy Preston, whose Fender Rhodes electric piano work lends authenticity and depth to the song’s soul vibe. Preston had been drafted into the sessions as soon as the project moved from Twickenham to Apple. He’d stopped by Apple to pay a visit to the group and was invited by Harrison to sit in on the sessions.

As Harrison said in interviews, he believed the keyboardist might be just the guy to help the sessions go smoothly and keep the four Beatles on their best behavior, as they often were when guest musicians were on hand. For that matter, if the Beatles were going to be true to the idea of recording with minimal overdubs, Preston could prove a useful addition to the group’s four-piece ensemble.

Preston and the Beatles had first met up on the road back in 1962, when the keyboardist was part of Little Richard’s band, and they’d remained friendly ever since. There was a sense of camaraderie there, as well as plenty of mutual respect. But the 11th-hour debut of this unlikely fifth Beatle, however gifted, is another element that leaves Let It Be feeling strangely like it’s not a “real” Beatles album.

Part of the reason may be that Preston, rather than the Beatles, provides some of the record’s strongest musical moments, from his electric piano comping and solos on Get Back and Don’t Let Me Down to his show-stopping solo organ break on Let It Be.

As it turned out, Ringo Starr’s budding film career put an end to the difficult sessions at Apple. In early February, filming was scheduled to begin on The Magic Christian, a feature that had Ringo. In need of a neat way to wrap up his documentary filming at Apple, Lindsay-Hogg hit on an idea that would lead to one of the most memorable performances in the history of rock on film: the Beatles’ final live performance on the roof of Apple headquarters on January 30, 1969.

As with many historic events, none of the participants thought it was particularly historic at the time it took place. No one knew it was the “last performance,” nor was it actually a performance in the traditional sense.

Few members of the “audience” – chance passers by on the streets of London and those lucky enough to be in an adjacent building – could actually see the band. It was just another day’s shooting for a film project in which several members of the Beatles were reluctant participants at best. But there is a kind of ragged glory in the fact that the Beatles – grouchy and on the verge of burn out – could still muster some of the old, live rock and roll chemistry.

While popularly regarded as the Beatles’ farewell, or at least the conclusion of Let It Be, the rooftop performance was followed by another day of recording down in Apple’s basement studio, which yielded the master recordings of McCartney’s two piano ballads, Let It Be and The Long and Winding Road, plus the acoustic guitar–driven Two of Us, which found McCartney playing his Martin D-28 acoustic. And then the Beatles went their separate ways for a while, Ringo to his film project, John and Paul to some of the most significant events in their lives.

Paul McCartney married Linda Eastman on March 12, 1969. Eight days later, John Lennon married Yoko Ono, and the couple went on to stage their historic “Bed-In for Peace” events in protest of the Vietnam War. Lennon also began to perform and record as a solo artist at the head of the Plastic Ono Band.

Get Back and Don’t Let Me Down were duly mixed and released as a successful single in the U.S. in May (in April for the U.K.). As 1969 wore on, Glyn Johns made two attempts to assemble and mix the Apple session tracks into a complete album, but both efforts were rejected by the Beatles. Meanwhile, by mid-1969, the Beatles were back at Abbey Road with George Martin producing the studio masterpiece that should properly be regarded as their final artistic statement, Abbey Road.

But the Apple sessions and film footage continued to haunt them, even as their business relationship grew increasingly strained and they hurtled toward the final breakup. Let It Be was selected for single release and had been spruced up with a few overdubs, notably a new guitar solo and lead overdubs played by Harrison through a Leslie tone cabinet given to him by Eric Clapton, and vocal harmony overdubs by Paul and Linda McCartney with George Harrison.

As 1970 dawned, plans were in place for Lindsay-Hogg’s footage – edited and released as a feature film, to be titled Let It Be. It was decided to release a soundtrack album, also named Let It Be, to coincide with the film. Once again, the Apple tracks came under review.

The original Across the Universe was a real piece of shit. I was singing out of tune and instead of getting a decent choir, we got fans from outside. They came in and were singing all off-key

John Lennon

Two songs previously not included in Glyn Johns’ album lineup were added to the proposed sequence. One was George Harrison’s I Me Mine, a song that the guitarist had written in the thick of the Apple sessions as he witnessed the tensions and strife of those long and difficult days.

Sung from the perspective of Harrison’s spiritual practice, the song laments the way in which petty ego identification and materialistic grasping cause endless suffering in the world. While Harrison had presented the song to the band during the Twickenham sessions, no master recording was achieved at that time. But since Harrison, McCartney and Starr are seen rehearsing it in the film (while Lennon and Ono dance apart from the group), it was decided that the song should be included on the soundtrack disc.

To achieve this, Harrison, McCartney, and Starr knocked together a quick recording of the tune at Abbey Road on January 3, 1970. Lennon was on vacation in Denmark at the time and, as in the film, did not participate.

Also selected for inclusion on the album was Lennon’s Across the Universe, a song that he had recorded back in February 1968, with high harmony vocals from two teenage female Beatles fans picked at random from the crowd outside of Abbey Road.

Across the Universe dates from a time when Lennon was also investigating Indian spirituality, and he included the mantra “Jai Guru Deva” in the song’s lyric. While the verses contain some of Lennon’s most lovely lyrical imagery, he was never completely happy with the composition, which was first released on a benefit album for the World Wildlife Fund in late 1969.

“The original track was a real piece of shit,” Lennon later recalled. “I was singing out of tune and instead of getting a decent choir we got fans from outside. They came in and were singing all off-key. Nobody was interested in doing the tune originally.”

To redeem this and other tracks, Lennon and Harrison, in concert with Allen Klein, enlisted legendary American record producer Phil Spector to do some emergency editing, overdubbing and remixing. As architect of the mid-Sixties “girl group” sound, Spector had pioneered the idea of the three-minute pop single as “little teenage symphony,” which is to say, a bona fide work of art.

He was one of the first producers to lavish an almost obsessive level of production attention onto rock and roll and pop singles, creating his much-vaunted “Wall of Sound” on classic hits by the Ronettes, Righteous Brothers, Ike & Tina Turner, and countless others.

Lennon was a great admirer of Spector’s productions. The producer could be difficult, confrontational and even violent. (He is currently serving a prison sentence for murder.) But Lennon, having come from a working-class Liverpool background and been handy with his fists as a youth, could deal with Spector’s brand of aggression. The two men had previously worked together on the Plastic Ono Band single Instant Karma and struck up a relationship. Spector would go on to produce several subsequent Lennon solo records.

There’s no denying that Spector appreciably beefed up Across the Universe, flanging Lennon’s acoustic guitar track for a thicker sound and adding massive orchestral overdubs to the track. The ascending cello line that trails the “Jai Guru Deva” refrain is particularly reminiscent of George Martin.

The 14-voice choir parts may have been suggested by Lennon’s impulse to use a choir on the original track. But Spector must have liked the choir, because he used it on the two other Let It Be tracks that received the full orchestra treatment: I Me Mine and The Long and Winding Road.

It should be clarified that Spector did not write the orchestral arrangements for any of these recordings. Brian Rogers did the Lennon song, while Richard Hewson arranged and conducted on the Harrison and McCartney tracks. But the lavish sensibility behind the orchestrations is pure Spector.

McCartney was incensed at what Spector did to The Long and Winding Road. The producer’s recasting of the track was even mentioned in the legal documents that made the Beatles’ dissolution official. But arguably, all that Spector did was to amplify the song’s inherent sentimentality. And who’s to say how much schmaltz is too much?

Let It Be, the album and film, came out in May 1970, just about a month after McCartney’s April declaration that he had left the Beatles. Viewed in that context, both releases carried much emotional resonance at the time.

Interest in the disc was revived in 2003 when McCartney released the digitally remixed and remastered Let It Be...Naked, excising all traces of Spector. Stripped of all its overdubs, the album may be more to McCartney’s original concept. But with or without Spector’s gloss, the sound that comes through loud and clear is of the world’s greatest rock and roll group breaking up.

- This feature was originally published in the June 2010 issue of Guitar World. 11 years later, the release of the Peter Jackson documentary, Get Back, would shine new light on the genesis of what would become the Beatles' final release as a band, Let It Be.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.