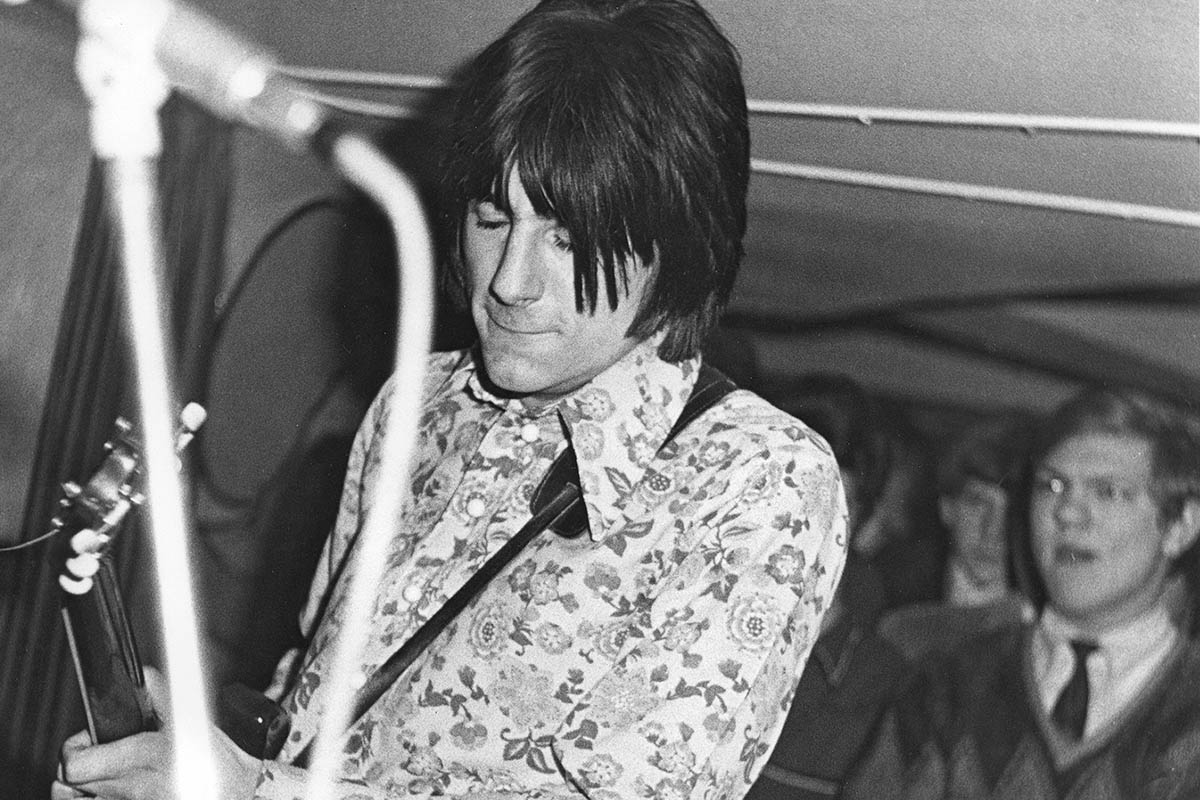

Remembering the Creation’s trailblazing guitarist Eddie Phillips, pioneer of the bowed guitar and feedback whisperer

With British Invasion record producer Shel Talmy, we unpack the legacy of the Creation. A fractious, brilliant band, who in Phillips had a guitar player with a groundbreaking style

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

1989, I sat with legendary British Invasion record producer Shel Talmy in his Hollywood Hills home. We were talking about all the iconic acts he’d worked with in the mid to late-’60s, from the Who and the Kinks to David Bowie. The conversation invariably turned to another great band from that era – one, sadly, not as well known today – the Creation, and their explosive, wildly innovative guitarist, Eddie Phillips.

“Had that band stayed together,” Talmy declared, “I’m convinced Eddie Phillips would be in the same category as Eric Clapton and all those people.”

The Creation were always the quintessential cult band, not to mention one of rock’s great guitar bands. The iconic ’80s-’90s dream pop/Brit pop label Creation Records – home to My Bloody Valentine, Oasis, the Jesus and Mary Chain, Swervedriver and other game-changing guitar groups – was named in their honor. Devoted fans include everyone from John Lydon to film director Wes Anderson, who put the Creation song Making Time in his 1998 feature film, Rushmore.

The hipsters all know, but the mainstream never quite understood. Even in their mid- to late-’60s heyday, the Creation barely hovered below the top 10 in their own land, the UK. As an American teenager in the ’60s, I only discovered them because Pete Townshend would sometimes namecheck them in interviews with the rock press. They were virtually unknown in America.

As guitarists and songwriters, Phillips and Townshend were very much kindred spirits. Both were using ideas from mid-’60s mod culture and cutting-edge art movements like Pop and Auto-Destruction to expand the horizons of live rock performance.

And a big part of that was expanding the electric guitar’s sonic horizons through the use of feedback and aggressive playing techniques. Phillips discovered that taking a violin bow to highly amplified electric guitar strings satisfied both requirements very nicely. Phillips inspired Jimmy Page’s own use of a violin bow a few years later. Talmy, who worked extensively with both guitarists confirmed this when I spoke with him in ’89.

“Of course Eddie Philips is the first-ever guitarist to use a violin bow on a guitar,” he said. “Which is where Jimmy Page got it. Eddie absolutely invented it. I got it on a record before Jimmy Page ever used it.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

That record was the aforementioned Making Time, the Creation’s hard-driving, feedback-drenched summer of ’66 debut disc. In the chaotic solo section, Phillips’ bowed Gibson ES-335 crackles and moans like some otherworldly menace.

With the feedback came the violin bow idea, just to get something out of the guitar that no one had ever heard before – something that was against the rules!

Eddie Phillips

Phillips had developed the bow technique in an earlier group, the Mark IV, initially using a hacksaw with a guitar string in place of the saw’s blade. But when that put three ugly gashes on Phillips’ then-brand-new Gibson ES-335, he decided to settle for more conventional instrumentation – a violin bow.

That 335 was Phillips’ main guitar throughout the Creation’s mid-’60s career. The instrument’s semi-hollow body no doubt played a huge role in Phillips’ throaty feedback timbres, especially when combined with one of the early Marshall 8x10 cabinets and an early 200W Marshall head. Phillips was employing feedback as early as the Mark IV’s 1965 single I’m Leaving.

“I was able to play the whole solo with feedback,” he later recalled. “I remember one of the engineers stopped the session, because they thought something had gone wrong, but I had to tell him that’s the way it was supposed to sound.”

“With the feedback came the violin bow idea,” Phillips told interviewer Chris Hunt, “just to get something out of the guitar that no one had ever heard before – something that was against the rules!”

Phillips’ initial idea was to use the bow to create open-string drones. “I thought maybe I could get a thing that would make the bottom E play while I can hammer on notes on the top E,” he said. But he was soon able to move beyond that, using the bow to create melodies.

In general, Phillips’ approach to feedback tended to be more melodic than Townshend’s – one thing that distinguishes these two great originators of the feedback-frenzied approach to electric guitar playing that Jimi Hendrix and others would soon embrace. This melodicism clearly anticipated Hendrix’s own use of feedback.

“It could be used musically,” Phillips said, regarding feedback, “and you could make a note of it; you could make it move. It’s strange, because at that time there were a few people who more or less got into that way of thinking and playing at the same time – like Pete Townshend and others as well.”

Much like the Who, the Creation were also exploring ways to end their live performances in some edgy, confrontational, Auto-Destructionist, smokebombs-and-mayhem kind of way.

To help promote their October 1966 single Painter Man, the Creation began climaxing their live sets with a cataclysmic performance of that song, during which lead singer Kenny Pickett would create an action painting on stage, wildly spraying paint from aerosol cans onto a large canvas while Phillips unleashed what he later described as a “violin bow freakout sort of thing.”

As practiced by celebrated painters such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Grace Hartigan, action painting had long been part of the mid-century fine arts scene. But it was something entirely new and exciting in mid-’60s pop musical performances.

“To my knowledge, the Creation were the first people to ever do an action painting onstage,” Talmy told me. “Kenny Pickett also came from art school, like Pete Townshend. It’s interesting how so many of those guys did. In fact, there was a big incident in Germany, in a very big hall that held about six to eight thousand people.

“He did an action painting with spray cans and he set fire to the damned thing and almost burned the theater down. He certainly got publicity! They were the first to do that, that I know of. And a lot of people copied it.”

“We had this lunatic of a road manager creating smoke from behind the picture,” Phillips himself further explained. “And then it snowballed. We thought: ‘Perhaps we’d better set light to the picture when we’d finished with it.’

“Painter Man was usually our last number and Ken used to rave about, painting this picture, which was then soaked in cellulose paint – which is quite flammable – and then a nutty roadie would put a match to it and the whole thing would go up in flames. The caretakers used to rush on with fire extinguishers. It was pretty dramatic… quite fun!”

Over a year later, Hendrix would light his guitar on fire at the Monterey Pop Festival, but that was a minor conflagration compared to the kind of pyro-psycho drama with which the Creation would routinely close their performances. It wasn’t until the early ’80s that industrial music pioneers Einsturzende Neubauten would start lighting stages on fire. Maybe there’s an influence there. Germany was the one major territory where the Creation were really big.

Their use of aerosol paint cans also anticipated the emergence of graffiti art by a couple of decades. And there’s a conceptual angle to the Creation’s fiery feedback freakouts that out art-schooled even Townshend. Creating a work of visual art and then destroying it in one dynamic action painting was something right out of the Auto-Destructionist playbook.

“I think the Who were actually influenced somewhat by the Creation,” Talmy told me. “I think a lot of people were influenced by them. They were a very, very innovative, good band. And fun guys, by the way – really bright and fun to be with.”

I think the Who were actually influenced somewhat by the Creation. A lot of people were influenced by them

Shel Talmy

In addition to the fire, frenzy and feedback, the Creation were also projecting films onto the canvases that Pickett would create on stage. Pink Floyd, of course, were also using film projections during their performances at London’s UFO club in early 1967.

And because groups like Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin became major stadium acts and album rock radio staples in the ’70s and beyond, history is often written in such a way that innovations like bowed guitar or the onstage use of film were solely the invention of these blockbuster groups.

Actually, these innovations and others were more the product of a zeitgeist – ideas that were in the air in London during that fertile mid-’60s period when mod morphed into psychedelia.

The Move – the group that would eventually turn into ELO – were smashing television sets on stage at the time. “Smashing” was a common adjective for something really exciting and cool, as evidenced by the title of the 1967 Swinging London movie, Smashing Time.

The Creation were a key catalyst in the crystallization of this highly creative cultural moment – one of the foundations for what would eventually be called classic rock.

Of course, none of this would mean much if the Creation’s music weren’t so great. Between 1966 and ’68 they produced a string of singles that were both hard-hitting and gloriously melodic.

These include primordial power pop gems like the Who-ish Biff Bang Pow, the proto-psychedelic How Does It Feel and the barely controlled six-string fury of Tom Tom. As co-writer of the band’s material, Eddie Phillips also looms large.

They hated each other. I tried everything to keep them together and they just would not do it

Shel Talmy

He wrote the Creation’s earlier songs with Kenny Pickett and the later material with Pickett’s replacement, Bob Garner, who had earlier been the band’s bassist. The Spinal Tap volatility of the Creation’s lineup and the animosities behind the frequent personnel shifts certainly didn’t help the band’s career.

“They hated each other,” Talmy told me. “I tried everything to keep them together and they just would not do it.”

Having signed the group to his own Planet Records label, Talmy had a vested interest in keeping them going. “When they broke up, I had a Number One with them in Germany, Holland and a couple of other countries,” he recalled. “It was in the Top 20 in the British charts and I had just made a very big deal with them for America. But I just could not hold them together.”

Like a highly volatile chemical compound, the Creation were simply too explosive to remain stable for very long. And they were just too much for a lot of people at the time – a period when the Kinks and the Rolling Stones were both banned from live performance in the United States, and the Who didn’t make it over here until two years into their career, in 1967. Like the Who, the Creation were punk before they had a name for it – only perhaps even more so.

“With the rawness of the music and, above all, with our attitude to music, we could have been the first punks,” Phillips once said. “It was our attitude to the music business. We really hated the business side of it.”

This is an outlook that’s rarely conducive to career longevity. Phillips exited the Creation in late 1967. In a revamped 1968 lineup, his replacement was Ron Wood, on hiatus from his stint as bassist in the Jeff Beck Group and, of course, destined to become a Rolling Stone.

This is another way in which the Creation are important. They stand at a crossroads of British pop music genealogy in the ’60s. Bassist John Dalton was a member of the Creation before going on to join the Kinks.

Longtime Kinks drummer Mick Avory played in one of the Creation reunion lineups. Scratch the surface of pop music history in this period and you’re likely to find the Creation. One of their temporary drummers, Dave Preston, possibly preceded Keith Moon in falling drunk off a drum stool.

After leaving the Creation, Phillips went on to play with soul singer P.P. Arnold (Patricia Ann Cole). He reunited with Talmy for a ’70s single, Limbo Jimbo, and reconciled with Pickett for a mid-’90s Creation reunion that ended with Pickett’s death in 1996. But there were lean years as well, and Phillips worked as a bus driver at one point.

Along the way his Gibson ES-335 was stolen and eventually surfaced in the collection of XTC guitarist Dave Gregory – who, coincidentally also worked as a driver (albeit of trucks, not buses) after leaving that group.

When the provenance of the instrument became known, Gregory restored it to Phillips, who, to this day, continues to lead the occasional Creation revival lineup.

Over the years, bowed guitar has been taken up by numerous high-profile players, ranging from Steve Vai and Mike McCready to Jonny Greenwood of Radiohead, Jon Por Birgisson of Sigur Ros and Lee Ranaldo of Sonic Youth. Many others employ electro-magnetic bowing devices such as the EBow. In this regard, we are all indebted to Eddie Phillips.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.