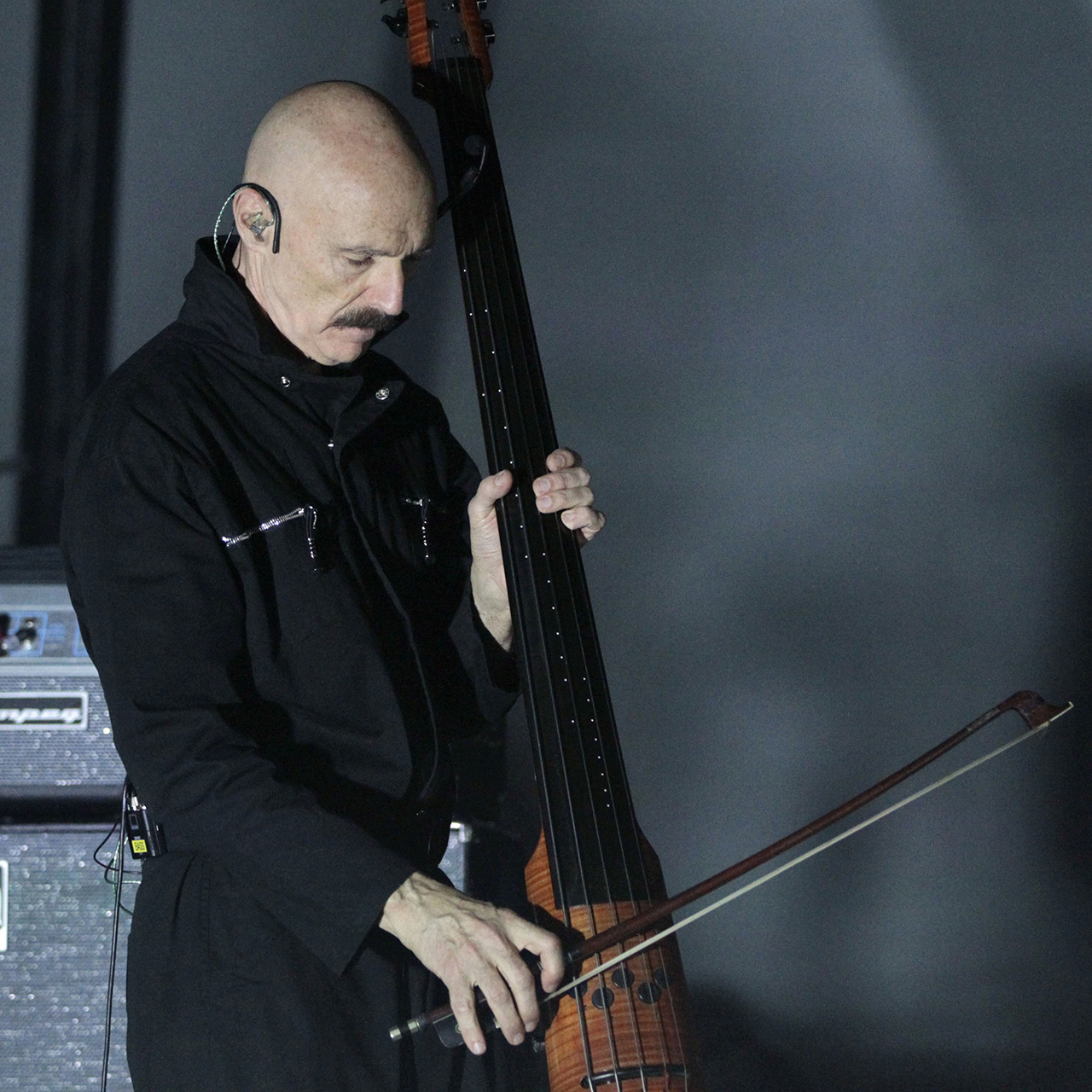

“It’s amazing to see Adrian Belew and Steve Vai playing together. My temptation is to pick up the camera! I have to remind myself to stick to my job playing bass”: For the King Crimson-channeling Beat tour, Tony Levin is a virtuoso among virtuosos

The bass icon on how he’s being challenged by parts he wrote, changing classic tracks – and when his Funk Fingers will make their next appearance

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

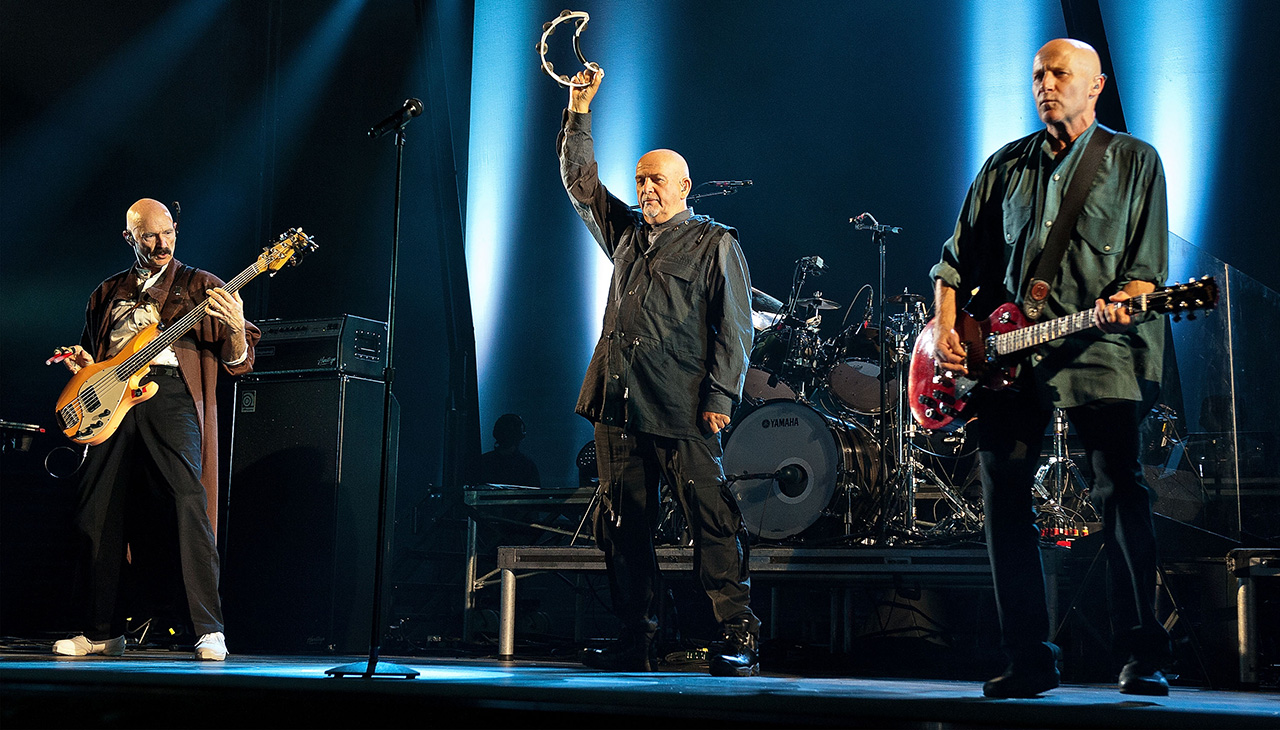

“How lucky am I that Bob Ezrin thought I was a really good heavy rock player?” Tony Levin asks Bass Player. One of the more prolific session artists in history, having appeared on over 500 albums, he’s heard in the catalogs of Peter Gabriel, King Crimson, Alice Cooper, John Lennon, Stevie Nicks, David Bowie, Tom Waits and Warren Zevon, among others.

“Bob asked me to play on Alice Cooper albums,” Levin says. “Then he asked me to join the rhythm section for this unknown guy named Peter Gabriel. I didn’t know Genesis – but how lucky I am that Bob heard that in my playing? Because from then on, it was pretty much non-stop.”

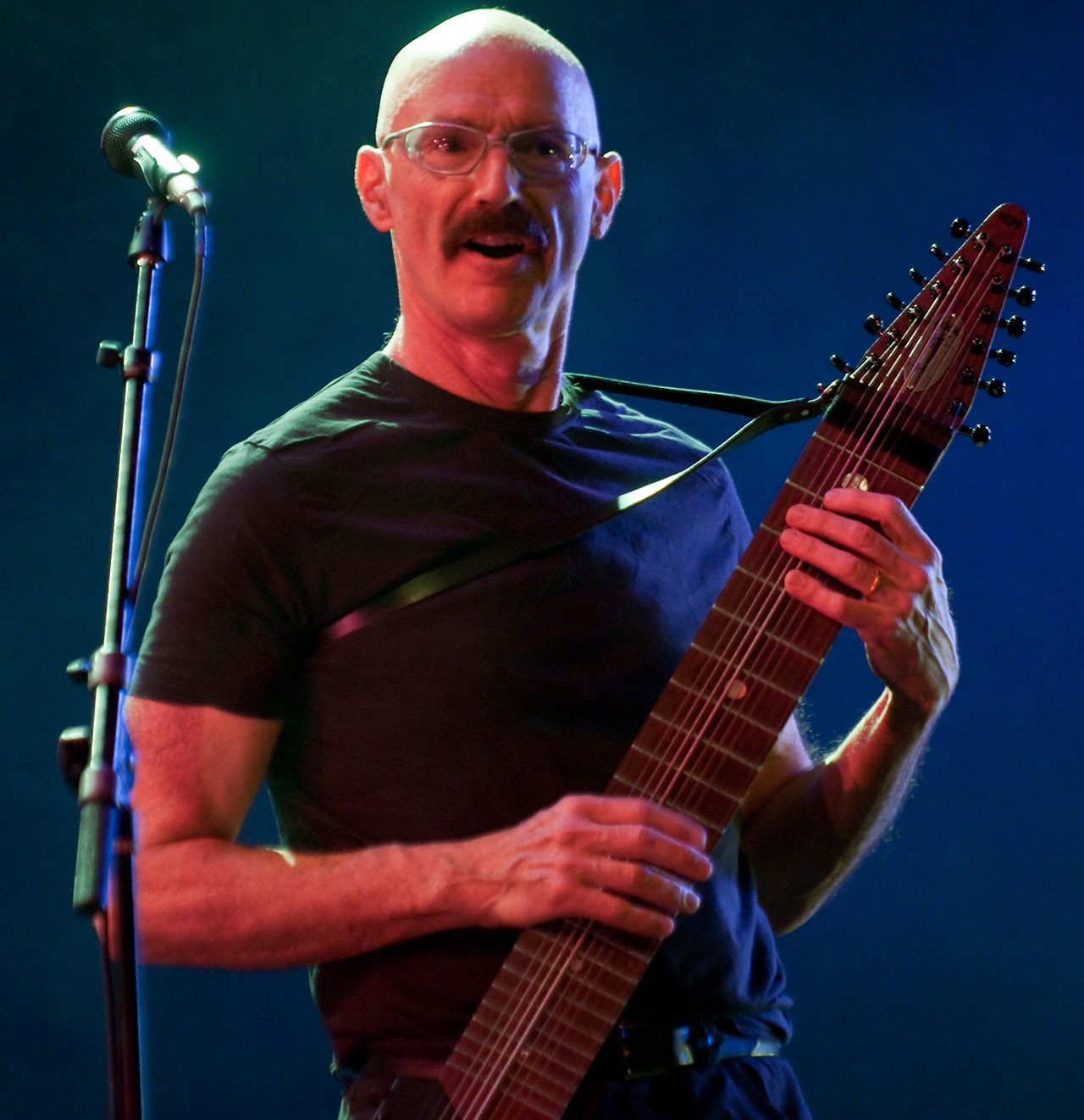

Born Anthony Frederick Levin in Boston, Massachusetts, he’s preparing for a 65-date tour alongside Adrian Belew, Steve Vai and Danny Carey, playing the ‘80s music of King Crimson under the Beat banner.

Cross-genre four-stringers like Les Claypool, Nick Beggs, Zach Cooper and Juan Alderete de la Pena cite him as an influence. “It’s not something I think about,” he says. “I just try to find something good for the piece.”

“It might end up with me playing a very sparse, low thumpy thing, or interceding with melody or playing chords. I’ve done that quite a bit by playing double stops, which helps the melody. I don’t have rules. When I react to a piece, I don’t approach it in terms of what a bass player ought to do. I just get a sense of what I’m going to do.”

He continues: “Bass players automatically listen and learn – even if it’s learning what you’re not going to do. I’m always listening and learning, and the players who influence me surprise me.”

He adds: “I learned not to copy what they did, and to appreciate the ability to step outside the expected and find something different but appropriate. That’s what I love about bass and bass players, young and old – they’re always teaching me.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

How are the preparations for the Beat tour coming along?

“I’m rehearsing daily. It’s sounding good. The players are amazing and we’re very excited about the tour. Adrian has been working for about five years to put this band together to play that music. He harkened back to how wonderful it was; and I agree.

“He and I, in contexts separate and together, have played the music many times over the years. It’s great music and certainly worthy of – I don’t know if you’d call it an all-star band, but specific players who love that music and want to revisit it.”

Earl Slick, as really good musicians do, gave me what I wanted and more

It’s music you helped create. Has it been easy to pick up again?

“It should have been because I made up the parts, but I’m finding it not so easy. I had some wild ideas about counter rhythms and counter time signatures on the Chapman Stick, so it’s challenging. But I like challenges, so the other guys are kicking me in the butt a little, and I’m trying to keep up.”

What’s it like watching Adrian Belew and Steve Vai chop it up on guitar?

“It’s amazing to hear and amazing to see. I’m a photographer in addition to being a bass player, and my temptation is to pick up the camera and take pictures of them about every 30 seconds! I have to remind myself to stick to my job and leave the photography for in-between pieces.”

What gear are you taking on the road with you?

“It’s very simple, not like in the ‘80s. I use a Neural DSP Quad Cortex multi-effects unit. We can’t have a lot of weight in the travel suitcase, so that’s very handy. It also has two stereo inputs and stereo output, which the Chapman Stick needs because it has a guitar and a bass side.”

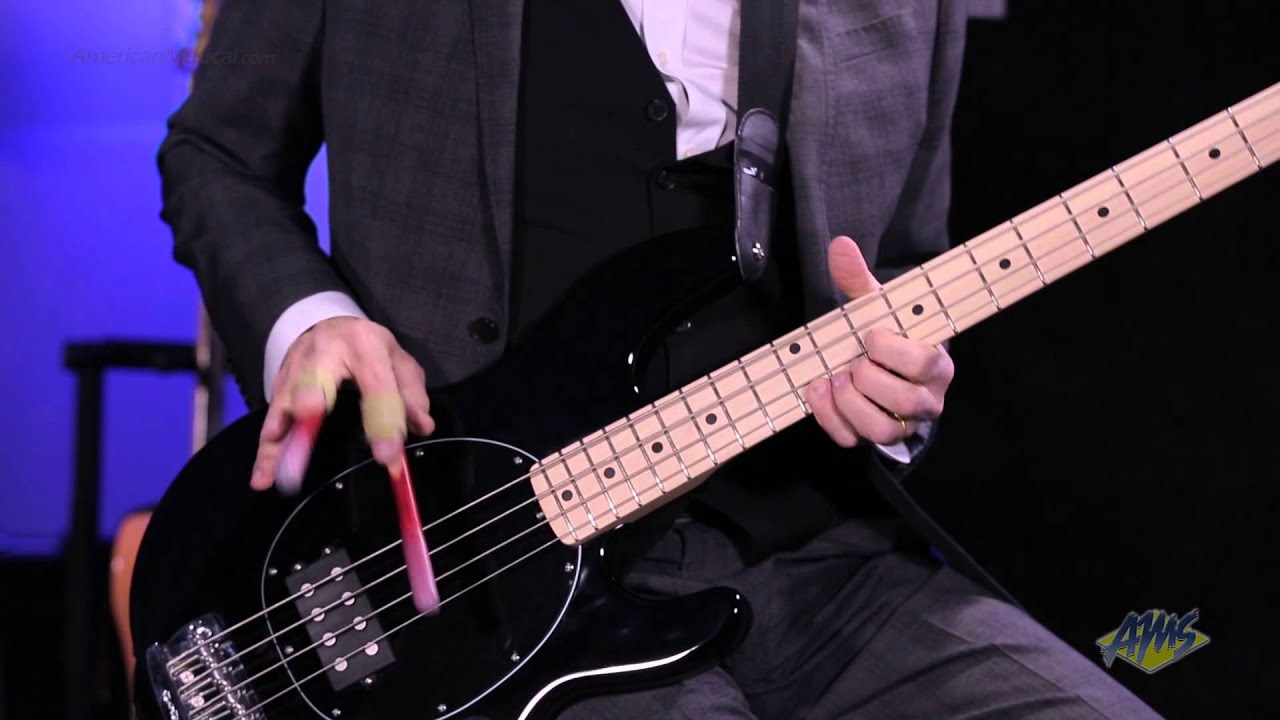

“I’m not using any effects pedals. I’ve got my old Music Man Stingray four-string bass – the one I painted the colors of the album cover of Three of a Perfect Pair back in the mid-80s. What could be more appropriate than dusting that off? And I have my five-string Stingray, which I’ll play on one or two pieces; but it’s mostly the four-string.”

You’ve got a new album, Bringing it Down to the Bass, out on September 13. What’s the lowdown?

“It features a lot of different basses, and I even took photo portraits of each of the them for the booklet with the CD. I like different sounds, so there are other great players on the album. That’s pretty darn important. In fact, to me, that’s the most important part of the album.

“I had a lot of material from years of writing at home. I tour so much that I couldn’t finish the album – a good problem to have. But I tried to get a sense of what this album should be, and I rejected about half the material for future stuff. It’s a nice representation of different bass techniques, sounds and instruments.

“Most of the pieces start with a bassline or bass effect. I got a sense of what the piece would be like, and then, pretty early in the process, I would think about what drummer I’d have on it, send it to them, and build the track.

“There were twists and turns; not always in the way I’d intended, but that’s great because I try to be open to things. I ended up with an album focused on bass sounds and techniques.”

The whole band would have turned and stared at me if I didn’t play the part that begins the song. Sometimes you’re locked into that

We know you’re a musical chameleon, but is there any carry-over in terms of style, regardless of the genre or gear?

“Very good question – but I’ll give you an unsatisfying answer! I don’t really think in those terms. I listen to a piece that’s being presented, and I react to it. In my musical brain, I begin to get a sense of what sound would fit; whether it should thump, be a long singing note, or something high.

”It’s not so much thinking of parts or notes, though there are exceptions, but trying to fashion an idea that will help the piece of music.”

Does working with an unorthodox songwriter, like Peter Gabriel, for example, spur you on to creative places you might not go otherwise?

“Recording is about working out the parts between the artist who wrote the piece, me, and the other musicians. Sometimes it changes a bit. I’m open to the ideas of the writer, especially if it’s Peter. He has a wonderful, outside-the-box way of thinking that inspired me to think outside the box too.

“It’s appropriate for his music, but not so much for some of the other music I did. It’s a process that I don’t think about until afterward, and it isn’t an intellectual process while it’s going on. It’s how I approach the music.”

How does your process look when it’s for your music?

“That’s different. If it’s my piece, I get the whole idea at once and try to record the bass part or the demo and see how it works. Then I’ll change tempos, and experiment with finding what I feel like works for the piece. It changes as it goes; it’s determined by the piece itself.”

Among the guests on the record are Earl Slick, on the song Boston Rocks.

“I brought Earl into the studio just to really rock out on it. He – as really good musicians do – gave me what I wanted and more. He surprised me with what he did. It’s a wonderful experience of bringing really excellent players into your music and seeing where they take it.”

Does being a photographer impact the way you approach bass and songwriting?

“I’m not aware of that happening; but the other way around, it happens a lot. One thing the players I love have in common is they’re really musical. Aside from their technique and style, they have a broad outlook on the world and the arts. That certainly helps.

“I’m not guaranteeing it’ll make you a great musician, but it helps. In that sense, I have an appreciation for the value of keeping a journal, writing poetry, and looking at the world as a writer and photographer.. There are aspects I can bring to it that are exactly what I bring to the bass.

My ‘toast bass’ survived a fire, but it dried out and it has a distinctive, thumpy sound

“Distortion, compression and accentuating the extremes – which are treble, the highs and the lows – are kind of like the blacks and the whites of photography. I have very much gone into the process of adjusting my photography the way I adjust my bass sound.”

You must be asked endlessly about Peter Gabriel’s Sledgehammer and In Your Eyes; but If you were to record those songs today, would you change anything?

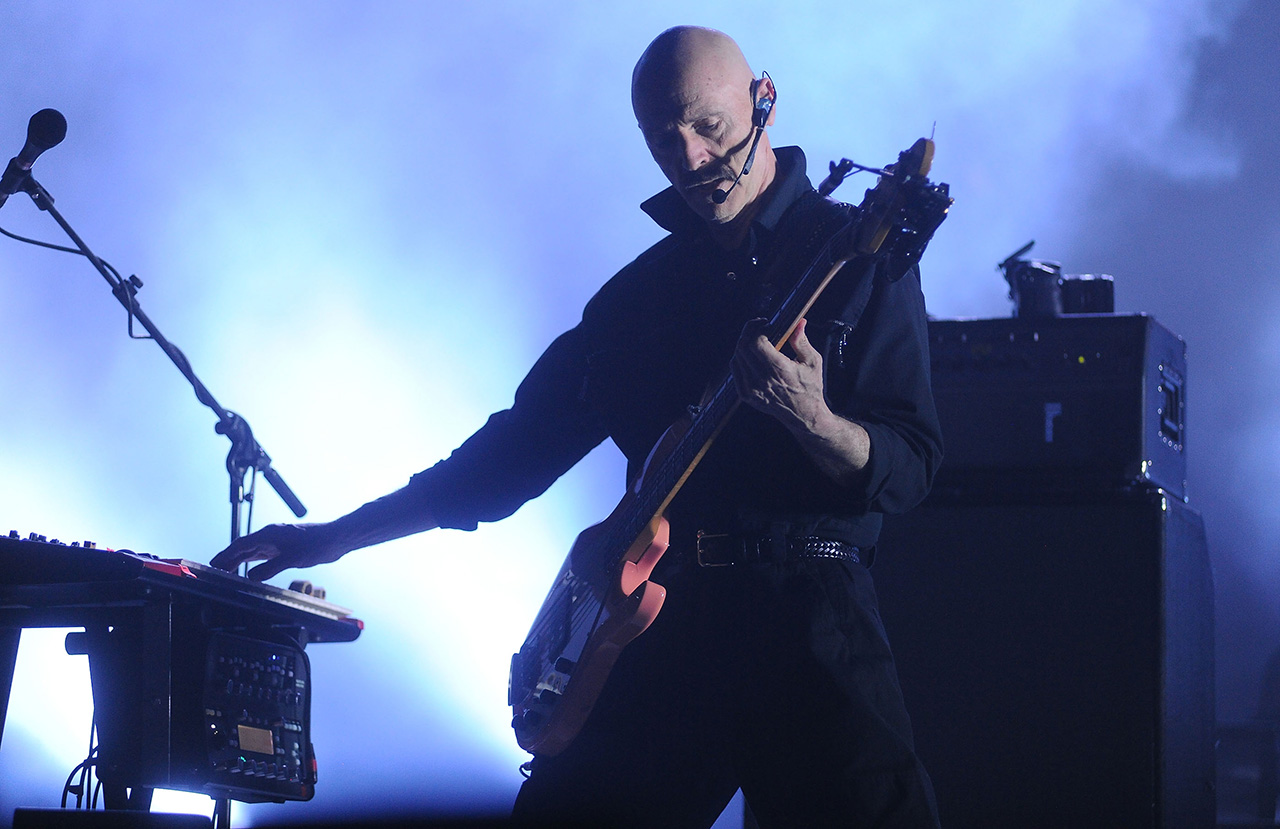

“The only experience I have had with Peter Gabriel recently is last year, when I was on tour with him. I played those songs, and I have different gear and instruments. Song by song, it’s different. When you get a song that has a distinctive bass part and it becomes popular, you get locked into that part.

“For instance, Don’t Give Up – I think the whole band would have turned and stared at me if I didn’t play the part that begins the song. Sometimes you’re locked into that; and that’s fine.

“I’m dealing with that right now because the Beat tour is playing the parts I made up in the ‘80s with King Crimson. And yeah, I’m changing them. With a song like Elephant Talk, I’m sticking to the original; but it’s in my hands. I can change them as it becomes appropriate. We’re not trying to be a cover band – if it strays a bit, that’s fine with me.”

Do you consider yourself a prog rock bassist?

“I ended up in the pool of progressive rock, not because of my choosing but because I was lucky enough to play with Peter Gabriel and King Crimson. I do a lot of progressive rock – but when I was choosing pieces for my album, the ones that weren’t appropriate were the very long, progressive rock compositions!’

What are the most important basses in your collection?

“Aside from some compression – usually the Universal Audio or Logic plugins – I try to feature the native sound of the bass I choose for each track.

“I especially like to use the vintage ones, which have their own sound, sometimes enhanced by the old strings and dampers. One track from the album, Floating in Dark Waters, seemed to call for my old Steinberger bass, the first one Ned Steinberger made – a fretless, distinctive sound, almost like an upright.

“My ‘graffiti bass’ is set up with high strings, making it very good for the funk fingers, so I used that on Road Dogs, starting with a featured funk fingers groove. My ‘toast bass’ survived a fire, but it dried out and it has a distinctive, thumpy sound. It seemed right for Espressoville.

What will get me through the darker nights is the two hours on stage. Or maybe more than two hours

“The track Side B is a barbershop quartet, but – breaking the rules of barbershop – I added a little bass solo in the middle, where I used my ‘belle bass.’ That’s a fretless that I’ve set up with strings a fourth higher; not to play higher, but to get that nice singing sound in the range that has the most sustain.”

There’s a recent picture of you sporting what appears to be a very long finger. What is that apparatus?

“That’s a ‘funk finger’ and I sometimes play with two of them on my fingers. They’re chopped-off drumsticks; they came about when, on Peter Gabriel’s So album, I had the drummer play on the bass strings while I fingered the fretboard notes.

“To play the Big Time part live, I needed the drumsticks on my fingers, hence the funk fingers. I’ve played with them a number of times since. They’re on Road Dogs on my new album.”

Are there any other oddball techniques you’ve been exploring?

“I did some hammer-on bass playing on the track Bringing It Down to the Bass. And I did what I call ‘fingernail harmonics’ on the solo of Espressoville. There’s lots of Chapman Stick playing on many songs.”

You’ve got a busy schedule. What are you most excited about?

“The album coming out is really special. I’m trying to let people know about it online; that’s what I do late at night, but the other 22 hours of the day are spent getting the music together for the Beat tour.

“I’m excited about that. Will it be strenuous? Yeah. Will I hold up? I hope so. What will get me through the darker nights and the not-so-pleasant parts is the two hours on stage. Or maybe more than two hours – because that’s what’s special to us. That’s why we do it. And that’s why we’re road dogs, as it were.”

- Bringing It Down to the Bass is available for pre-order now.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.