Yamaha Guitars: Pacific Crossing

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Originally published in Guitar World, November 2009

In 1969, a little-known Japanese instrument company took a chance and

shipped a batch of guitars to the U.S. The rest is history. Guitar World celebrates 40 years of Yamaha Guitars.

“Woodstock, the first man on the moon and the first Yamaha guitars to arrive in the U.S.—it all happened in 1969,” Yamaha Guitar marketing manager Dennis Webster notes. That year marked the start of Yamaha’s rise from a maker of guitars for the Japanese market to the top-selling guitarmaker in the world and the top-selling acoustic and acoustic-electric guitar company in the U.S.—not to mention the producer of some of the most ubiquitous bass guitars on the planet.

Yamaha played a pivotal role in the emergence of Japanese guitars in the Seventies as world-class contenders, equal—and in some instances, superior—to their American and European counterparts. Down through the years, Yamaha guitars and basses have found favor with rock icons like Carlos Santana, Paul McCartney, Bruce Springsteen, Dave Navarro, Wes Borland of Limp Bizkit and Troy van Leeuwen of Queens of the Stone Age. And Yamaha stringed instruments have been equally popular with singer-songwriter legends like Paul Simon and James Taylor and jazz and rock virtuosi like Nathan East, Frank Gambale, Martin Taylor, Billy Sheehan and John Patitucci.

“The Japanese are a people who are very proud of their workmanship and it shows,” Webster says. “They’re very meticulous in their research and study of great instrument design, and they have a long tradition of high-quality woodworking. At Yamaha, we’ve been working with wood for over 100 years now. And it’s not just guitars. Every day, we’re selecting and procuring premium woods for pianos, drums, marimbas…you name it. There’s a lot of expertise there.”

WAY BACK WHEN

Venerable American guitar brands like Martin, Gibson and Washburn proudly trace their histories back to the 19th century. Yamaha’s pedigree dates back to that age as well. The company, originally called Nippon Gakki Co. Ltd., was founded in 1897 by organ-maker Torakusu Yamaha. Then as now, the company was headquartered in the Japanese city of Hamamatsu. By 1941 Yamaha had begun to branch out into guitar making, focusing initially on steel- and nylon-string acoustics that were sold only in Japan at first.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But the guitar operation really kicked into high gear during the mid Sixties, when Beatlemania became a global phenomenon and garage bands began forming everywhere. In Japan, right-wing cultural conservatives marched in protest of a 1966 appearance by the Beatles at Nippon Buddokan in Tokyo, claiming that the Liverpudlian quintet were polluting the “purity” of Japanese youth. But the guitar R&D team at Yamaha took a more pragmatic approach to the rock and roll invasion from the West, wisely reasoning that, if you couldn’t beat them, you could most certainly join them.

That same year, Yamaha debuted its first electric guitar, the SG7, one of the most wonderfully wild-and-weird designs in the company’s history. The asymmetrical body features a spiky horn at the treble-side upper bout, which is balanced by a softly rounded, swelling curve at the bass-side lower body bout. Meanwhile, the slender, elongated six-on-a-side headstock is arguably an early precursor of the Jackson/Charvel, “hockeystick” headstock of the hair metal Eighties.

Yamaha’s Hirotaka Takanashi designed the body and headstock, with Masatoshi Suzuki, Takeshi Uchida, Shunichi Matsushima and Ryozo Maki handling technical design under the leadership of Kiyohiko Ito. Long lists of names like these are common in Yamaha guitar history. While American guitar history, and indeed much of American culture, is based around the myth of the rugged individual—Leo Fender, Les Paul, Fred Gretsch—Japanese culture places more emphasis on the collective energy of many people working in harmonious creative collaboration. This outlook has proven to be a great source of strength in Yamaha’s history.

One more key figure in the SG7 design was guitarist Takeshi Terauchi, leader of the pop group the Blue Jeans, who acted as an artist consultant for the instrument. “The Blue Jeans played with Yuzo Kayama, who was kind of the Japanese Elvis Presley,” says Yamaha assistant general manager Kiyoshi “Jackie” Minakuchi. “Yuzo Kayama was a movie star and wrote lots of songs. And because the Blue Jeans played with him, they were pretty big at the time. Takeshi Terauchi was inspired by some American-made electric guitars when it came to designing the SG7, but he was also concerned with making it very comfortable to play.”

The SG7 had a 12-string sister, the SG12a, and bass guitar brother, the SB7. There was another wildly elliptical bass design, the SB1C, and a few hollowbody arch-top “surrealistic Rickenbacker” knockoffs, the SA15 and SA15D. It’s a shame that these instruments never made it to America in the mid Sixties. If ever there was a guitar meant to join forces with Vox Phantoms and Danelectro Longhorns, it’s the SG7 and its shapely siblings. The guitar has developed something of a cult following. It was reissued in the mid-Nineties as the SGV (the V stands for Vintage) and has found favor with modern players like Meegs Rascon of Coal Chamber.

As it happened, Yamaha’s acoustics, rather than its electrics, were the first of the company’s guitars to make an impact in the U.S., when the company began exporting them to the country in 1969. The FG Series acoustics were among the earliest to arrive. One of these, an FG150, wound up making its debut on the first evening of the Woodstock Festival on August 15, 1969, wielded by singer Country Joe McDonald. In the years that followed, Yamaha acoustics would acquire a solid reputation as roadworthy instruments that offered plenty of value for a modest price.

A SEVENTIES SENSATION

To meet growing worldwide demand for Yamaha guitars, the company opened a new factory in the town of Kaohsiung in Taiwan to supplement Japanese production. The opening years of the Seventies saw Yamaha moving toward more conventional designs with its electric guitars, like the dual-humbucker, single-cutaway, Les Paul–ish SG45. The timing was right. The British Invasion of the mid Sixties and psychedelic explosion of the late Sixties had made rock and roll a big business. As a result, many of the major U.S. guitar companies had been bought up by corporations that, in their corporate wisdom, compromised quality in order to increase profit margins.

What these new corporate masters of the American guitar business hadn’t counted on was serious competition from Japanese manufacturers, who could offer high-quality and affordable pricing (largely because workers in Asia were paid less than their American counterparts). As the Seventies wore on, Japanese guitars began to shed the “cheap and cheesy” image they’d acquired in the Sixties and command serious respect.

One development that seemed to clinch the arrival of Yamaha, and Japanese-made instruments in general, was the high-visibility adoption of Yamaha guitars by Carlos Santana. A stalwart Gibson player earlier in his career, Santana was captivated by the SG175, a dual-humbucker solidbody with a distinctive, pointy dual-cutaway body shape that resembled something like a double-cut Les Paul. It would become one of Yamaha’s most instantly identifiable body shapes. “When Carlos Santana visited Japan in 1974,” Jackie Minakuchi says, “Yamaha supported his tour and had a chance to show him the SG175. He played it in concert and ordered a 24-fret version of the SG175 with a Buddha inlay. He said that he was influenced by the Buddha spiritually.”

Like many guitarists in the Seventies, Carlos’ musical quest at the time was to achieve greater sustain. As part of this general obsession with sustain, the neck-through-body design gained great popularity. Fashioning a guitar’s neck and central body from the same piece of wood allows for a more uniform vibration pattern, which results in greater sustain. In addition, this design prevents energy loss that occurs when vibrations travel from the guitar’s body and into a separate neck. As the SG175 was a set-neck instrument, Santana had Yamaha make him two 175 prototypes with a neckthrough-body design.

These prototypes, in turn, set the stage for the neckthrough Yamaha SG2000. To increase sustain even further, Santana had Yamaha affix a bulky brass sustain plate to the body, right by the tailpiece. Brass was the magic metal of Seventies guitar design. All manner of guitar hardware was fashioned from the dense metal in the endless quest for greater sustain. And so, by 1976, one of Yamaha’s most iconic guitars had come into being.

One might even say that the SG2000 was to the Seventies what the Strat and Les Paul were to the Fifties. The Stratocaster and Les Paul are instruments that strongly reflect the design aesthetics and tonal preoccupations of the Fifties but which have transcended the era in which they were created, to become timeless classics. In the same way, the Yamaha SG2000 and its spin-off SG Series guitars are products of the Seventies that are still very much in use today. With its neck-through design and distinctive silhouette, the SG2000 offered a unique option to the Gibson and Fender archetypes.

The fact that a highly respected musician like Santana was willing to lay aside his Gibsons and pick up a Yamaha spoke volumes. He played his Yamaha guitars on the late-Seventies and early Eighties albums Inner Secrets, Marathon, Zebop! and Shango, and soon other high-profile guitarists followed suit. Bob Marley, John McLaughlin, Robben Ford and Bill Nelson were all Yamaha SG2000 players at one point or another.

The Yamaha SG guitars became such a presence in the market that, during the Eighties, the company was obliged, at the insistence of Gibson, to change the model designation from SG (which had stood for “solid guitar”) to SBG (“solid body guitar” to avoid confusion with Gibson’s own SG models. This minor shift in nomenclature has done nothing to diminish the popularity of these Yamaha electrics. Just this year, the company released a new update of the classic design, the SBG3000, which will be produced in a limited run of only 40 guitars. “It’s a 40th anniversary product,” explains Minakuchi. “This is a heritage guitar for us. That body shape has been very good for Yamaha.”

Santana’s 1974 SG175 with the Buddha inlay has become an iconic instrument, but it is hardly the only gorgeous and mystical custom inlay job that Yamaha has done for rock’s elite. In 1977, the company created a custom CJ52, “country jumbo,” acoustic for John Lennon, which sported a curling red dragon inlaid on the guitar’s black body, along with a circular yin/yang symbol. The inlay work employed a traditional Japanese technique called Maki-e, a style of inlay not usually employed on musical instruments because it requires the use of a high-humidity steam kiln that wreaks havoc on the music-making properties of wood. Yamaha’s custom guitars builders found a way to pull it off, creating the dragon from a drawing by Lennon himself. The instrument is the most expensive Yamaha guitar ever made.

Lennon had become interested in Yamaha acoustics after playing a custom, black CJ52 acoustic that the company had produced for Paul Simon. The celebrated American singer-songwriter is a longtime fan of Yamaha acoustics, which the company custom-makes for him with slightly smaller bodies to fit the artist’s compact frame. But Simon was hardly alone. Yamaha acoustics became high visibility items during the Seventies. James Taylor played an FG2000 and L55 Custom, while David Lindley favored an L51. Jimmy Page played Yamaha acoustics during Led Zeppelin’s 1975 world tour and would later make Yamaha his acoustics of choice for the Page/Plant Unleaded tour in the Nineties. And Bruce Springsteen relied heavily on a CJ52 during the fertile Eighties phase of his career.

Yamaha’s reputation for building great acoustic guitars grew in 1980 with the introduction of the APX line of electro-acoustics. This Yamaha series was a bold step away from traditional acoustic guitar design with its thin-bodied, single-cutaway guitars finished in bright, solid colors and outfitted with bridge-mounted piezo pickups. And in thinking outside the big wooden box of conventional guitar design, Yamaha created an electrified acoustic that was ideally suited to live performance. The thinner body helped reduce feedback and was aided in this job by an onboard EQ optimized for the task of notching out feedback-friendly frequencies.Espoused by country star Wynonna Judd and countless others, the APX became standard equipment for live acoustic playing in all genres during the Eighties.

THE METAL EIGHTIES

At the dawn of the Eighties, Yamaha responded to the burgeoning new trend toward hot-rodded metal axes initiated by the rise of Eddie Van Halen. The company’s initial bid for the market was the SF3000, an electric guitar equipped with a single humbucker and a whammy bar for executing the dive bombs and horse whinnies that so liberally adorned the playing of EVH and others. Yamaha scored a major coup when Van Halen bassist Michael Anthony fell in love with the company’s BB2000 bass, relying on it heavily for the band’s 1984 album and standout tracks like “Panama” and “Good Girl Gone Bad.”

The BB, or “Broad Bass,” Series had been introduced in 1977. The instruments employ a neckthrough-body design similar in concept to the SG/SBG2000 and its offspring. Paul McCartney became an early BB proponent, wielding a BB1200, as seen on the video for his tune, “Coming Up,” during the early Eighties.

Metal bass virtuoso Billy Sheehan also became a BB convert, laying aside his beloved Fender Precision Bass for a Yamaha BB3000 in 1984. He collaborated with the company on a modified BB3000, carefully reproducing the neck dimensions of other specifications of his P-bass. It was the first of many custom and signature models Sheehan and Yamaha would create together.

If the Seventies had been the coming out party for Japanese guitars, the Eighties was Japan’s senior prom. Yamaha and fellow Japanese giant Ibanez had a particularly strong hold on the metal market, and with good reason. The hair metal phenomenon found a particularly responsive audience in Japan, and indeed many stars from that era still enjoy the proverbial distinction of being “big in Japan.” Moreover, the musicians who created the sound and look of Eighties metal were relatively unconcerned with the rock, blues or country music traditions of the Fifties and Sixties, and there was less impetus for them to play the venerable American guitars so closely associated with those decades.

Yamaha’s all-out bid for the Eighties shred/hair metal market came in 1987 in the shape of the pointy RGX Series guitars and RBX basses. These instruments were equipped with all the features that shredders and aspiring shredders were lusting for: 24-fret ebony fingerboards, 24 3/4–inch scale lengths and a doublelocking trem system that enabled players to pull up on the whammy bar.

But while Yamaha guitars and basses zeroed in on the metal market during the Eighties, this was by no means the company’s sole focus. Yamaha developed a comprehensive line of acoustics and electrics in the Eighties—everything from jazz archtops to traditional Gibson/PRS-ish solidbodies like 1988’s Image Series. One characteristic shared by many Yamaha electrics is a very thorough and well thought-out system of electronics. This trait can be attributed to the meticulous rigor of Japanese design coupled with a desire to move beyond the three-position toggles and five-position switches of traditional electric guitar design. A good example of this design impetus is the H.I.P.S. (Hybrid Integrated Pickup System) featured on many Yamaha guitars starting in the late Eighties. It allowed any pickup on an H.I.P.S.-equipped Yamaha guitar to be switched on or off and from humbucking to single-coil operation. Some models allowed the pickups to be switched from passive to active.

Yamaha’s all-encompassing guitar line, in turn, has long been part of a much bigger picture that includes significant market shares in electronic keyboards, pianos, drums, recording studio equipment and P.A. gear. It all adds up to a manufacturing/marketing juggernaut, massive economies of scale and a remarkable level of R&D symbiosis.

FROM JAPAN TO NORTH HOLLYWOOD, WITH LOVE

In 1989 the Yamaha Guitar Development facility opened in North Hollywood, California. The idea was to harness those massive Yamaha manufacturing and marketing engines to what was basically a small, focused, boutique-style, super-hip custom shop. With more rock stars per square mile than any place else on earth, L.A. was definitely the place to tap into the most recent, advanced and ambitious thinking about what the ultimate electric guitar or bass might look, sound and feel like. This cutting-edge thinking could be implemented in guitars that could then be mass-produced by Yamaha’s factory facilities in Japan and Taiwan, with their long-standing reputation for precision craftsmanship.

Luthier Rich Lasner, formerly of Ibanez, headed up YGD in its earlier years, working with Ken Dapron and Leo Knapp. Lasner and his American colleagues worked closely with Minakuchi in Japan. Two of the initial instruments created by this international team were the Pacifica and the Weddington, which are also among the very few Yamaha guitars to have received actual model names rather than just numbers. The Pacifica was very much Yamaha’s response to the Superstrat trend of the late Eighties and early Nineties. The Weddington, which takes its name from the street where YGD is located, was a Les Paul–style guitar done up in the most high-class manner possible, with highly figured flame maple tops and all the trimmings.

YGD collaborated with Japan on several other outstanding instruments in the Nineties, including the AES1500, a thinline hollowbody archtop with a Bigsby tailpiece that was in the vintage Gretsch spirit but outfitted with Yamaha’s Q-100 soapbar style pickups. YGD also worked with Billy Sheehan to create the Attitude bass, some models of which incorporated Sheehan’s well-regarded stereo pickup configuration, featuring his DiMarzio “woofer” pickup in the neck position.

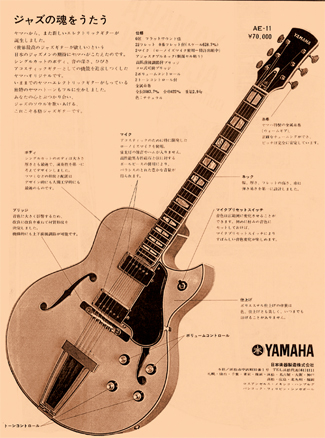

But not all great Yamahas came out of North Hollywood in the Nineties. Working from the Japanese HQ, Minakuchi developed the AEX1500 jazz archtop with guitarist Martin Taylor. He was also instrumental in creating the TRB bass series. Among his other of his design hallmarks is the use of piezo bridge pickups in instruments that don’t usually have piezos, such as archtop electrics and bass guitars, as well as advancing the concept of the six-string bass. “In 1990, there were not many six string basses,” Minakuchi says, “especially from the big companies. So Yamaha was the first to do that, working with artists like John Patitucci and Nathan East.”

A NEW CENTURY

So far the 2000s have brought several key strategic changes for Yamaha guitars. For one, John Gaudesi came aboard as the Custom Shop manager and chief designer at the North Hollywood facility, bringing with him experience he’d amassed at ESP, Valley Arts and Charvel/Jackson. Prominent among Gaudesi’s recent projects for Yamaha is a signature guitar he designed in conjunction with Wes Borland of Limp Bizkit fame. The instrument’s jaggedly asymmetrical body shape reflects Borland’s flair for the visual arts.

“Wes is an artist as well as a musician,” Gaudesi notes. “So when he came in for his first design session, it was actually pretty refreshing. Instead of working from existing body styles and shapes, Wes sat right down, sketched something and said, ‘This is what I want.’ ” The sketch was pretty crude, but it ended up being exactly the way the guitar is shaped. It’s almost like a surrealist version of an archtop guitar. For the f-holes, I took a photograph of the tattoos on Wes’ forearms, digitized that, and that’s exactly what’s on the guitar.” The guitar’s back, sides and center block are all carved from a single piece of alder. Yamaha calls this the Takumi-Kezuri method of construction, but it also happens to be exactly the way the classic Rickenbacker semi-hollowbody guitars of the Sixties were constructed.

The locking tremolo system on the Borland guitar is a Yamaha Finger Clamp Quick Change system, developed by Jackie Minakuchi in an attempt to find an alternative to the hex nuts that make other locking systems so cumbersome and inconvenient to use. Gaudesi says, “Originally we were going to do a vintage trem on Wes’ guitar. He wanted to keep it really traditional at first. But then Limp Bizkit decided to get back together and Wes said, ‘Man, there’s no way I can play that stuff without a locking trem.’ So I changed some drawing and specs on this trem that Jackie was working on. I thought it would be great to get Japan involved in the guitar as well, so they could feel some personal ownership. So I got both sides of the world involved, as far as Yamaha goes. Everybody was truly contributing and really excited about the project.”

Gaudesi’s retro futurist flair can also be seen in the signature model guitar he designed for Troy van Leeuwen from Queens of the Stone Age. It’s a triple-pickup guitar based around Yamaha’s FA2200 thinline solidbody but dressed up by Gaudesi with elegant Art Deco f-holes and a retro-groovy switchplate on the upper bout.

“The f-holes are a newer version of something that’s been in the Yamaha design family for quite a few years,” Gaudesi explains. “But that little plastic switchplate is something I had to fight hard for. I thought the two toggle switches would look like a modification or repair job if we didn’t put something there to show that it was an intentional part of the design. We’re not breaking any crazy new ground with that switchplate, but it does give a nod to a lot of the Sixties Italian guitars that had a lot of plastic all over them. But obviously this is a little better quality.”

The North Hollywood facility has grown in importance over the years, to the point where Yamaha undertook a major expansion of the space in 2006, more than doubling the square footage, from 5,000 to 11,000, and adding guitar and drum showrooms, a recording studio, photo studio and repair workshop. To reflect the facility’s enhanced functionality, its name was changed from Yamaha Guitar Development (YGD) to Yamaha Artist Services Hollywood (YASH).

“This is a perfect place to talk to artists,” says Minakuchi, who left Japan to work full time out of YASH as co-director of the facility. “Whenever we need to, we can call artists and invite them to check out a new prototype or product. We can get their opinion very easily and I can talk to Japan that same day and say, ‘Please change this,’ or ‘Maybe this is not a good idea.’ ”

Meanwhile, Yamaha acoustic guitars became a major priority for Dennis Webster when he joined the company circa 2003, coming over from Gibson. “Yamaha had been really focusing on electric guitars,” he says. “To me, it seemed like we’d gotten away from our roots. We decided to put the focus back on acoustics and take back the market share that we’d had in the past.”

The move coincided with the 30th anniversary of Yamaha acoustics in 2003. Under the design leadership of Hiroshi Sakurai, the company’s top-of-the-line L Series was revamped with a new 90 degree X bracing system and a “C Block” neck joint that enhances the traditional dovetail neck joint design for greater stability and resonance. In addition, Yamaha’s more affordable FG Series acoustics were upgraded with solid sitka spruce tops throughout the line, replacing the laminated tops on some models, and a bracing pattern similar to the one employed in the new L series.

As a result of all these efforts Yamaha has gone “from the number-five spot in the American acoustic market to the number-one position it occupied in the past,” according to Webster. The latest acoustic models from the company are a pair of electrified nylon-string guitars: the NCX, which is a traditionally shaped nylon-string guitar, and the NTX, which boasts a thinline, single-cutaway body. Both were developed in consultation with the popular guitar duo Rodrigo y Gabriella. Webster describes these new instruments as “crossover” nylon strings.

“There are more pop and rock players wanting to add that nylon-string sound to their palette. You see artists like Jason Mraz and John Mayer doing it, and that’s why we came out with those models. The nylon-string sound is a cool sound to have. It’s always good as a fourth or fifth guitar. It really adds a different dimension to your playing. But at the same time, you’re never going to get a true, traditional classical player to play an instrument with a cutaway and electronics. That’s why we still make the GC Series classical guitars for the higher end players.”

The NCX and NTX will be the first Yamaha nylon-string guitars to employ the company’s A.R.T. (Acoustic Resonant Transducer) onboard amplification system, which is used in popular Yamaha steel-string guitars like the APX and CPX Series as well as some L Series acoustics. It does away with the need for a bridge-mounted piezo pickup, which has long been a standard component of acoustic guitar amplification schemes but is often decried for its characteristic “quacky” sound.

Instead, says Webster, the A.R.T. system employs “two transducers, which are kind of like little microphones, mounted inside the guitar body. We use one on the bass side and one on the treble side, and you can blend them any way you want. The good thing about this system is that it really cuts down on feedback and surface noise if you’re playing very percussively or aggressively. The transducers are insulated with neoprene rubber and wood spacers.”

Over time, the company has amassed a diverse and impressive line of guitars and bases. Many established models like the SBG, Pacifica, AES and RGX electrics, the BB basses and L Series acoustics are still in production and well on their way to classic status. Meanwhile, innovative new models like the Borland and van Leeuwen signature electrics and NCX/NTX nylon-strings continue to impact the guitar playing universe.

“I’m working with John Gaudesi every day on new projects and ideas,” Minakuchi says. “Our workshop is filled with prototypes.”