Burzum: Heart of Darkness

Originally published in Guitar World, April 2010

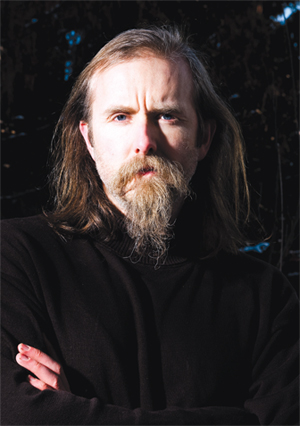

Burzum’s Varg Vikernes has disowned the Norwegian black metal genre he helped create in the Nineties. After an absence of more than 15 years, he’s back with a new album that takes his musical vision deeper into the abyss.

In 1991, 18-year-old guitarist Varg Vikernes founded one of Norwegian black metal’s most important bands upon a simple, yet powerful, platform: to bring darkness into the world. Vikernes’ ambitious musical pursuits and extreme, anti-Christian ideology quickly placed him and his band, Burzum, at the heart of Oslo’s burgeoning scene, which also included bands like Mayhem, Immortal, Darkthrone and Emperor.

But over the next couple years, Vikernes’ dark intentions grew beyond his art. He turned to violent crime, activities that culminated in 1993 when he burned several churches and murdered the scene’s figurehead, and his one-time friend, Euronymous, who was the guitarist for Mayhem. The following year, Vikernes was convicted of these crimes and sentenced to 21 years in prison.

In May 2009, after serving more than 15 years of his term, Vikernes was released. He remains unrepentant of his crime, and his time in prison has done nothing to dim his musical vision, a fact made clear on his new album, Belus. If anything, he has an even greater sense of purpose, purity and creative hunger than when he began, which has resulted in his split from the black metal community. “I am no friend of the modern so-called ‘black metal’ culture,” Vikernes wrote on his web site in November 2009. “It is a tasteless, lowbrow parody of Norwegian black metal circa 1991–92, and if it was up to me it would meet its dishonorable end as soon as possible. However, rather than abandon my own music, only because others have soiled its name by claiming to have something in common with it, I will stick to it.”

Vikernes’ musical history reaches back to the mid Eighties, when the guitarist was in his early teens. “Until I was around 12 or 13, I only listened to classical music, mostly Tchaikovsky,” he says. “But around that age I started listening to Iron Maiden, and that’s when I purchased my first guitar, a pearl-white Westone.” Maiden’s classic dual-guitar attack and epic songs soon inspired Vikernes to seek out heavier and more extreme metal, such as Kreator, Celtic Frost, Bathory, Destruction and Megadeth, which he played in endless rotation on his stereo for the next several years. “My scope was rather narrow,” the guitarist says. “But my biggest inspiration was always early Iron Maiden, because it was the only band I knew for some time, and, as we all know, Iron Maiden is great.”

Kreator, Destruction and Megadeth helped feed Vikernes’ love of thrash, but it was the nefarious themes, gritty production and dramatic imagery of black metal first-wavers Bathory, Celtic Frost and Venom (whose 1982 album Black Metal effectively named the genre) that eventually inspired him (along with other second-wave black metal contemporaries Mayhem, Darkthrone, Emperor and Immortal) to take the genre to new artistic heights, and dangerous illicit lows.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But first, the guitarist had more thrashing to do. Around 1988, Vikernes formed his first band, the classic-thrash-inspired Kalashnikov, which later changed its name to Uruk-Hai, reflecting his affinity for Middle Earth role-playing games and the evil Orc creatures from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings fantasy novel. After a year playing thrash metal in Uruk-Hai, Vikernes moved on to join the local Bergen, Norway, death metal band Old Funeral, which also included future Immortal members Abbath and Demonaz. The guitarist appeared on their Devoured Carcass EP, but left in 1991 after becoming frustrated with the constraints of their straightforward style, which featured stock death metal elements such as palm-muted, tremolo-picked guitars, guttural vocals and relentless double-kick drumming.

At the time, the death metal of U.S. bands like Morbid Angel, Death and Deicide had grown. No longer a stateside underground phenomenon, it had become the style du jour among extreme metalheads throughout Norway. While many musicians welcomed this upsurge with open arms and saw the potential to create a strong scene, Vikernes wanted nothing to do with it. “The main objective was to be anti-trend,” he says, “and to show all the trendy death metal bands out there—and at the time there were a lot of them—that it could actually be done differently.”

To this end, Vikernes began to blaze an independent course, the first step of which was the adoption of his new band name, Burzum. “As most Tolkien fans should know ‘burzum’ is one of the words that are written in Black Speech on the One Ring of Sauron,” Varg wrote on his web site in December 2004. “The last sentence is [Ash nazg thrakatulûk agh burzum-ishi krimpatul] meaning ‘one ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them.’ The ‘darkness’ was of course my ‘light.’ So all in all it was natural for me to use the name Burzum.”

To further the mystique, Vikernes adopted the pseudonym, Count Grishnackh (the surname inspired from an Orc of Sauron in Tolkien’s The Two Towers) under which he would release his music. “If people knew that Burzum was just the band of some teenager that would sort of ruin the magic, and for that reason I felt that I needed to be anonymous,” Vikernes wrote in 2004. “So I used a pseudonym, Count Grishnackh, and, on the debut album, I used a photo of me that didn’t look like me at all to make Burzum itself seem more out-of-this world, and to confuse people.”

The final step to artistic autonomy came when Vikernes opted to play every instrument himself. In this way, there would be no other musicians to whom he would have to make concessions.

And so Burzum was born. Between 1992 and ’93, Vikernes recorded four full-length Burzum albums—Burzum, Det Som Engang Var, Hvis Lyset Tar Oss and Filosofem—which many consider to be the truest examples of the Norwegian black metal sound. Burzum’s cold guitar tones and tremolo picking, bleak synth landscapes, lo-fi production and tortured screams helped lay the foundation for the desolate sound and one-man-band approach that stretches all the way to current underground U.S. black metal artists like Xasthur and Leviathan.

“The idea with Burzum was not only to make original and personal music, but also to create something new: a darkness in a far too light, safe and boring world,” Varg wrote in the same 2004 essay. “Unlike 99 percent of all musicians, I didn’t play music to become famous, earn money and get laid. Instead, my motivation was a wish to experiment with magic, and try to create an alternative reality. Burzum was supposed to be the vessel, the magic weapon.”

Vikernes took his musical alchemy seriously. The music he wrote wasn’t intended for live shows. Instead, “it was supposed to be listened to in the evening, when the sunbeams couldn’t vaporize the power of the magic, and when the listener was alone, preferably in his or her bed, going to sleep,” he explained on his web site in 2004.

If Vikernes’ musical philosophy seems esoteric, it’s because it is. As is often the case when describing new sounds, words cannot capture the experience. To truly appreciate this music, you must listen to it. A good example of Burzum’s haunting atmospheres can be heard on “Det Som En Gang Var,” the opening track from Hvis Lyset Tar Oss. The 14-minute cut begins with a slow, trebly, heavily distorted minor-key guitar progression that is mirrored by somber synth keys. The gloomy ambience patiently builds for several minutes before the eruption of thundering double-kick war drums and the grim main riff. At the five-minute point, Vikernes’ vocals enter like the screams of a man being disemboweled at the bottom of a well, leading the listener through the remainder of the hypnotic, and disturbing, track.

In tandem with Vikernes’ solitary pursuit of new musical landscapes, he became further entwined with the so-called “Black Circle” of musicians, which including members of Emperor, Immortal, Enslaved and Darkthrone, that congregated at Helvete, the downtown Oslo record store owned by Euronymous.

The scene at Helvete was initially fertile. Among the artists, bonds were formed and ideas shared. Burzum was signed to Euronymous’ Deathlike Silence Productions, and Euronymous tracked the solo on “War,” from Burzum’s self-titled debut. Vikernes played bass on Mayhem’s 1994 release, De Mysteriis Dom Sathanas, and contributed lyrics to two Darkthrone albums, Transilvanian Hunger and Panzerfaust, while Emperor guitarist Samoth added bass to a couple tracks on Burzum’s Aske. But the creativity soon gave way to chaos.

Violence was no stranger to the genre. Mayhem vocalist Dead would often cut himself onstage, and in 1991 he killed himself with a shotgun blast to the head. The following year, a series of escalating criminal actions began emanating from musicians within the Helvete scene. Some of these were exercises in anti-establishment terrorism, while others were simply anarchic and hateful.

Christianity became a target. Some within the scene saw it as an invading religion that eradicated Norway’s ancient Viking and pagan belief systems. Youths within the scene began burning historic wooden stave churches across the countryside. Among the perpetrators were Vikernes and Emperor guitarist Samoth. Eventually, murder reared its head. In August 1992, Emperor drummer Bård “Faust” Eithun killed a stranger in the woods outside of Lillehammer, after the man reportedly sexually propositioned him.

Vikernes’ seed of darkness—planted in his music and rooted within the Black Circle—came into full tragic bloom on August 10, 1993. A rift had developed in his friendship with Euronymous. Soured business deals or struggles for dominance in the scene may have been responsible. Whatever the cause, Vikernes made a surprise visit to Euronymous’ Oslo apartment in the early hours of the morning. The circumstances of that pre-dawn meeting are unclear, but the result is not: Vikernes killed Euronymous by stabbing him multiple times.

He was arrested nine days later, and in May 1994 was tried and convicted for the murder as well as for church burnings. He received a 21-year sentence, the maximum penalty in Norway.

Despite his incarceration, Vikernes managed to stay musically active. After several years inside, he gained access to a synthesizer and tape recorder and created two dark ambient albums, Dauði Baldrs and Hliðskjálf (1997 and 1999, respectively). While they are impressive considering the circumstances in which they were created, they only hint at the strength of his previous works.

Now that Vikernes has been released from prison, he’s once again picked up his ax and with Belus is attempting to reclaim his position among the Norwegian extreme music elite.

In the following interview with Guitar World, Vikernes discusses a range of topics—including his fondness for Swan Lake and underground house music, the gear with which he created Burzum’s distinctive sound, and how he grew as a guitar player on Belus—in the only way he knows how: as fiercely independent, outspoken and inflammatory as ever.

GUITAR WORLD What inspired you to start playing guitar, and what kind of guitar was it?

VARG VIKERNES It was a pearly-white Westone [Japanese-made guitars from the Eighties], but that’s all I remember. After some Googling, I found only one Westone guitar that looked like mine, and that was the Spectrum LX (X198) Pearl Burst. But I am not sure if that’s even the one. Mine was rather cheap; I purchased it from a schoolmate’s big brother in 1987 and only paid 3,500 Norwegian kroner for it [about $550 at the time]. I never had any problems with it, even though I never treated it with the respect it deserved. I used it for all my guitar recordings until, and including, Filosofem. I would still be using it today if it hadn’t been stolen in 2003.

I’m not sure that I even remember exactly why I started playing. I think it must have been because my brother purchased a guitar from the same guy, and he asked if I wanted to buy one as well. It was not too expensive, and I had the money, so why not? I wasn’t very enthusiastic about it at first, but it grew on me, and after some time I played more than I should have, being a school kid and all.

GW Who were some of your early inspirations when you started?

VIKERNES I only listened to classical music until I was 12, the age when I found Iron Maiden. Then, after some time I realized that there were other bands around as well. I began listening to early Kreator, Endless Pain and Pleasure to Kill; Celtic Frost, Morbid Tales; Bathory, Blood Fire Death; and Destruction, Infernal Overkill. I also listened to Megadeth. None of my friends liked this kind of music, except one who—unlike me—liked AC/DC and another one who—again, unlike me—liked Metallica.

GW How much was Quorthon [Bathory’s founder] an influence on you? There are definite similarities between your musical styles, as well as the one-man-band configuration.

VIKERNES When it comes to Bathory, I only listened to [1988’s] Blood Fire Death album until I discovered, and very much liked, [1990’s] Hammerheart. Later on, I started listening to his earlier—and certainly poorer—albums, as well. Bathory was a major influence on me in 1991–92, but [Burzum’s] one-man-band configuration came not from Quorthon’s influence. In fact, in 1991 I didn’t even know Bathory was a one-man band. Instead the configuration came as a result of me being, well, egotistical. I want everything done my way, or not at all.

GW Did this attitude develop as a result of your experiences playing in Old Funeral [Vikernes was the guitarist for the Bergen-based group in 1991]?

VIKERNES In Old Funeral, I was only a guitarist in someone else’s band. I could not decide everything, and they had begun following a trend I didn’t like. So I left and returned to my old thrash metal project called Uruk-Hai. At the time the other musicians in Uruk-Hai, drummer Freddy Steimler, vocalist Jo and the bassist—I don’t even remember his first name—were busy elsewhere, so I decided to simply do everything myself and shortly after changed the name to Burzum.

GW Have you been influenced by bands or guitarists outside of the metal genre?

VIKERNES One of the albums I have enjoyed the most is called Within the Realm of a Dying Sun, by a [darkwave] band called Dead Can Dance. I heard it for the first time in 1992 and listen to it quite often. I’m not too fond of their other albums, but this one is excellent. Another album I’ve liked for a long time is Die Propheten by a German band called Das Ich. Fantastic album, although I must say I am not too fond of their other albums, either. Generally speaking, I am not a “band-liker” but instead likes individual albums or tracks. rather a cherry-picking sort of fellow who Also, being ridiculously conservative and narrow-minded beyond all reason, I tend to stick to the albums I like and rarely if ever bother to check out new music.

My biggest influence in music, metal included, is the music of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, especially Swan Lake and The Nutcracker, and other classical music. I also like some underground “white label” house music [records by unsigned or anonymous artists which are often pressed with blank labels], traditional Russian music and European medieval and ancient music. If I had some Bronze Age lurs [an S-shaped trumpet], I’d be using them as instruments on the next Burzum album.

GW Speaking of instrumentation, you created a very distinctive guitar tone on early Burzum albums, like Burzum and Det Som Engang Var. How much of that lo-fi sound was a calculated decision, and how much of it had to do with the quality of gear you had access to back then?

VIKERNES I intentionally used a poor-quality amp on the debut album so that I could get a sound as different as possible from what was “in” at the time. For one of the guitars, I used a tiny, 10-watt Marshall amp. In hindsight, it was a terrible combination with the other guitar track, which I recorded using a proper 60-watt Peavey amp. It was okay, but it wasn’t really the sound I wanted. So when I recorded Det Som Engang Var a month later, I used a proper 60-watt Peavey for both guitars. The sound on Det Som Engang Var was exactly what I was looking for at the time.

GW Am I right that the popular sound you were reacting against was the palm-muted progressive death metal of Death, which emphasized technical mastery and song complexity?

VIKERNES I wanted to show that you didn’t have to sound just like Death or Morbid Angel, the leading extreme metal bands at the time. If you cannot create your own sound and just try to sound like the popular bands, what’s the point in making music? Do we really need a hundred Morbid Angel bands out there, even if perhaps a few of them sound better than the original? My solution was as much an anti-trend statement as it was a choice based on my own musical taste. Perhaps it was not the best solution, but it worked...to some extent anyway.

Then, in 1992, all the former Death and Morbid Angel followers in the Norwegian death metal scene started to copy the style of Mayhem, Darkthrone and Burzum instead, and a new trend was born: so-called Norwegian black metal. They changed band names to avoid being identified as former death metal bands, and the [original point of black metal] was lost.

GW On albums like Filosofem and Hvis Lyset Tar Oss, your guitar sound gets significantly “colder,” with much more treble. You also start to weave in more haunting synth lines. What influenced your musical progression during that time?

VIKERNES You forget that the Burzum tracks weren’t recorded or released in a chronological order, so I am not sure if we should focus too much on a musical progression from 1991 to 1993. Also, I used the exact same guitar equipment and Peavey amps on all these albums, with the exception mentioned above, and the same drum kit too, as far as I remember. The only exception in this context is Filosofem, where I didn’t use a guitar amp at all but used a normal [hi-fi] stereo amplifier instead, in an attempt to create something entirely different. By March 1993, I wasn’t after the anti–death metal sound anymore but rather an anti–black metal sound. Because, as I mentioned earlier, all the followers had of course started to do their best to sound just like Darkthrone and Burzum. And with great success. They didn’t try to sound like Mayhem because Mayhem hadn’t released anything worth listening to at the time.

GW So when you decided to create the anti–black metal sound, where did you look to for inspiration?

VIKERNES Burzum’s sound progression was influenced by a number of things. The wish to create an anti–black metal sound is one thing. But also my own and the sound technician’s skills had progressed by then. On the debut, we were both green when it came to producing this type of music. It was a new thing. Further, it took some time for me to find what I liked and to understand how to produce what I liked. I actually first recorded the “Dunkelheit” track, from Filosofem, for Hvis Lyset Tar Oss, but it was a complete failure. The track itself was okay, but the recording was terrible. The next time around I succeeded, because of the different sound and the fact that I used a click track. For some weird reason I recorded the first three albums without the use of a click track. Go figure.

GW You were becoming more isolated from the scene during this time, too. How did that affect your music?

VIKERNES In 1992 and 1993 I spent a lot of time alone, because I was sick and tired of the follower mentality of the metal scene in Norway. If I went out, I only rarely went to the metal pubs or places like that. Instead, I went to an underground club in Bergen, called Føniks, where they played rave and house music really loud until six o’clock in the morning. None of the metalheads could stand the music, so I was left alone. I stood there, in a dark corner, all by myself and listened to the mesmerizing music until they closed the shop. Then I would go home, inspired to play the guitar. I think underground house music influenced my music a lot in this period. It made it more monotonous, and the tracks became longer, which made it sound different from most other metal music.

GW Another big part of Burzum albums is the patient layering of sounds. Can you speak about how this song construction creates Burzum’s bleak, tense atmospheres?

VIKERNES The verse-chorus-verse-chorus-solo-verse-chorus structure was overused by too many bands already, and I wanted to do things differently. The Burzum music was supposed to tell a story, from beginning to end, and synchronize with the concept of the album. Hvis Lyset Tar Oss is a good example: the first track softens you up, the second and third wear you down and the last track makes you relax, ideally putting you in a certain sleepy mood. The music was never created for live shows, or any other type of shows for that matter, but for lone listeners trying to relax and let their thoughts wander off to a dream world at the end of the day. There are no guitar solos, because they change your dream state and tend to make you think of yourself showing off onstage with a guitar. For many, that’s a dream, too. But not the Burzum dream I was trying to create.

All the albums were created with this in mind, but the first two were created for vinyl, so they don’t work very well on CD. They were less successful in this context compared to the latter two metal albums. I think Hvis Lyset Tar Oss is more successful in this context than Filosofem, which is the most successful of them all.

GW You’ve recently been released from prison. How did your incarceration influence your music? Did your solitude take you to new levels, either musically or spiritually?

VIKERNES I’m not really sure what to say. I don’t think being in prison influenced me very much in any way. I lived very much in solitude when I was out too, and my stay in prison was not very problematic. I was not a rat, rapist, or pedophile, so the others prisoners had no problem with me. I was not a junkie or a drunk, and I had no mental problems, so I had no personal demons to fight while there. I was anti-Christian, anti-American and had killed a guy with a knife, so the Muslims had no problem with me. I was polite and reasonable, so the guards had no problem with me. I was treated like radioactive shit by the authorities, so pretty much all the other prisoners thought very well of me. The stay in prison probably made me a little more extreme, in every way. When I was incarcerated, I pushed the pause button, so to speak, and then when I was released I pushed it again, and continued my life as if nothing had happened. It was a long pause, all right, but still...

GW How has the world changed since the start of your prison sentence?

VIKERNES Everyone has cell phones and the internet. All cars look the same and are built to last only a few years. Downtown Oslo looks even more like downtown Baghdad—and I know, because I lived there for one year, back in 1979. The quality of all goods seems to have dropped dramatically. Nothing I come into contact with works like it should, perhaps because everything seems to be made in China these days. The metal scene has grown tremendously. A lot has changed, but mostly it’s the same old depressing story: a world going down the drain, and a species jumping willingly into the abyss. Most human beings are falling as we speak. They confuse this “wonderful” feeling of falling with flying and think it’s evidence that everything is fine. But they’re falling, and they haven’t hit rock bottom yet. When they do, it’ll be too late.

GW You’ve never been afraid to take musical, or personal, risks. Do you ever look back at any part of your life and wish you had done something different?

VIKERNES No doubt. But really, it’s useless to regret anything you have or haven’t done. Also, sometimes it is necessary to make mistakes to be able to arrive at the best conclusions. Most of the times I wish I had done something differently, I end up thinking that perhaps it was the right thing after all. Not there and then—when I’m facing the adverse effects of my mistakes—but shortly after, when most of the pain is gone and the wounds are partially healed, so to speak, and only the fading scars are left to remind me of what happened.

GW Do you regret any of the earlier work in your catalog?

VIKERNES My first few albums are perhaps not very good by today’s standard, but they were the first steps I needed to take. They were also the steps a few other bands needed to stand on to be able to go further and make other, and perhaps much better, music. Without my “old crappy albums,” they would not have been able to know that it was possible to do things that way. I don’t see the early Burzum albums as “mistakes.” Even though they are far from perfect, I don’t wish I had done anything differently.

GW How has your guitar playing evolved over the many years that you’ve been playing and writing music?

VIKERNES In the early years it was important to play the guitars as technical as possible, to show off or perhaps just to get better. As the years went by, I stopped caring about such things and started to play music instead, so to say. My guitar playing evolved and became more and more distinctive, I think, because I did not play the music of others. The idea was that if I learned from others I would not create anything new myself later on, but instead I would only make music that sounded just like the music of my teachers. And why would that be any good? If it wasn’t something special, it would be meaningless. Now, I have not heard any new metal music since 1996, so I really don’t know what kind of music is played these days, but at least I imagine that my guitar playing is still distinctive.

GW You’ve stated that the new album is a concept record dedicated to the ancient European god, Belus. Where did you look for your research?

VIKERNES The concept of Belus was used because I know something about this after doing research for my book, Trolldom og Religion i Oldtidens Scandinavia [Sorcery and Religion in Ancient Scandinavia], which I intend to translate and publish as soon as possible.

GW Describe the process of recording Belus.

VIKERNES It took about seven days to record, and everything was recorded at Byelobog Studios in Norway. Being a one-man band I need less time to record an album than normal bands do. So spending even seven days felt like a lot. I really took my time recording this album, and it was very important to me to get the sound I wanted, especially since I have not released anything for over 11 years. The best things about doing everything yourself is that there is no dissent in the band, no arguments and no time spent on nonsense. The recording process was fairly straightforward, since I had recorded the whole album a few times on one of my own computers using Tracktion 2 [music production software] at my home studio. By the time I started to record in the studio, the tracks were already properly arranged and I knew exactly how I wanted them to sound.

GW How does Belus compare, production-wise, to some of your earlier work?

VIKERNES Not sure what to compare the album to. Maybe Hvis Lyset Tar Oss, only with much better production and sound. I used much better equipment and had more experience—2009 offers much better recording technology than 1992 and 1993 did. I also gave myself longer time to record this album, and that will hopefully be heard in the overall production and sound of the album. But rest assured, it still is Burzum. It sounds like Burzum, and it’s not a polished or overproduced album by any means.

GW What instruments did you use for the recording?

VIKERNES I used my own Peavey equipment: a PXD Twenty-Three guitar and a 120-watt Peavey 6505 head with straight and slant cabs. The PXD Twenty-Three and the Peavey head and cabs really gave me the sound I wanted for this album. It was important to me since Belus was written mainly using the guitar, and I wanted the guitar sound to be prominent in the production.

GW You’ve written on your web site that instead of giving up on black metal because of what it’s become—a degraded scene filled with drunken, feminine-dressed weaklings—you’re returning with a new album. How does Belus offer a musical and ideological purity that the current musical scene lacks?

VIKERNES I can’t say that Belus offers anything but more of Burzum, and note that I don’t think of Burzum as being black metal at all. I am not a part of any musical scene, so I really don’t care about such things. I couldn’t care less about the so-called black metal scene. From my point of view, I have nothing in common with contemporary black metal bands. It would be very unnatural for me to compare myself with them or to identify with them or their scene. If black metal fans also happen to like my albums, that’s just fine. But it changes nothing when it comes to Burzum.

Furthermore, I really have no clue what the current musical scene is like, let alone what it lacks. I jumped on a train back in 1991, but I bailed out even as it was about to fill up in 1992. Their train has traveled for 18 years since then—in a different direction—with them believing all along that I was still on the train. But I wasn’t. I’ve been running as fast as I could in the opposite direction...and I’m probably lost by now.